Effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic

- Right now the world is battling the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and many theater productions and festivals have been cancelled or postponed in the midst of it all. We hear that one production of yours at the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater had a performance in France that was in danger too, wasn’t it?

- Yes. Our production of ARIKA (a duo dance work by former Forsythe Company dancer Yasutake Shimaji and rapper Roy Tamaki) that was scheduled for performance on March 13 and 14 at the Maison de la culture du Japon in Paris came very close to being cancelled.

There was no problem when the performers arrived in Paris, but the after I arrived in Paris three days before the performance, the French government declared a prohibition on any gatherings with an audience of over 1,000, and the day of the first performance on the 13 the government lowered the prohibition to audiences of 100. We spoke with the theater and agreed to limit the audience to less than 100. So, before the scheduled start of the performance at 8:00 p.m. the staff were on the phone calling people for reservation cancellations and when the time came, we indeed had an audience of less than 100, including the staff, so the performance could go on. On the morning of the 15th the order went out for all public theaters to be closed, and on the 16th President Macron declared the lockdown to start on the 17th. We were surprised at how quickly France went with the lockdown decision as the conditions were changing by the hour. - The dance and rap duo ARIKA by Yasutake Shimaji and Roy Tamaki was also performed at the 3rd HOTPOT East Asia Dance Platform (*1) held in Yokohama in February, after which it got invitations from several festivals as evidence of how well it was received by overseas directors.

- Yes, ARIKA is a work that premiered five years ago in Aichi. Shimaji had been saying that he wanted to create some works that could be re-performed numerous times. And because places like the Agency for Cultural Affairs puts priority on new works [for debut], the theaters around Japan tend to favor new works as invited works. So, when we were thinking about how to get audiences that included not only core dance fans but also general audience not familiar with dance to come to repeat performances of repertoire pieces, it seemed that we needed to add other aspects to the dance, and that is when the name of the rapper and musician Roy Tamaki came up. And, since he was also interested in working seriously on stage-oriented pieces, we decided to ask him to work with us. It was an idea that connected to our Mini Theater Selection program launched in 2015 (a performance series for the Mini Theater of the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater focused on cutting-edge crossover and experimental works), and this was the first full-fledged contemporary dance production we undertook after the shift in management. We arrange a tour of performances to Chiryu City, Kasugai City and Toyokawa City in Aichi and also outside the prefecture to the Kanagawa Art Theatre (KAAT) and Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM). Then there were re-stagings at HOTPOT and the Toyama City Arts Hall (AUBADE HALL). Both of these are public theaters, and performances in France were the first overseas.

- For the opening of HOTPOT, which was held at the same time as the Yokohama Dance Collection, you also presented a work titled ON View: Panorama, that the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater co-produced as an international project. This was a work jointly created by the Australian choreographer and video artist Sue Healey and a cast including dancers from Australia, Hong Kong and Japan and others. The composition included short films reflecting each dancer’s style and inner worlds, a video installation and a live [dance] performance.

- Yes. There happens to be a sister city relationship between Australia’s Victoria State and Aichi Prefecture, so there have been a variety of collaborative programs primarily with Melbourne since our Art Theater opened. Since 1997, we have had Sue [Healey] and her company’s dancers do projects with our local dancers in Aichi and with other unique Japanese artists (such as [stage] director Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, music directors Tsuneo Imahori and Naruyoshi Kikuchi and video artists IKIF, etc.), and based on the results of those projects , we participated in the 1998 Melbourne International Arts Festival. Later, in 2002, we also had them create a work titled NICHE for the Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service’s Dance in progress 2002 program. Also, director Anna CY Chan of the dance department of Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District organization liked the Australian version of ON VIEW so much that she decided to make a Hong Kong version. It happens that I have known Anna for some 20 years, so when the proposal arose for a joint production between Australia, Hong Kong and Japan, I thought it would be a great opportunity to further develop our relationships. At the Arts Promotion Service we had a film/video works curator and we actively pursued dance and video collaborations, so with crossover media works so prominent now, I wanted to use online, exhibition and performance to explore again the possibilities of the dance-video relationship.

I was given responsibility for selecting the Japanese dancers, so I chose five: Naoko Shirakawa, Kenta Kojiri, Ema Yuasa , Nobuyoshi Asai and Saori Hara, and for about two weeks in September 2018 we shot video footage of them. After that, two dancers from each country were chosen and we entered the creation stage in 2019 at the Kinosaki International Arts Center. The work was presented in Yokohama and Aichi, and in 2020 we had planned productions in Hong Kong and Sydney, but the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic caused those to be postponed, and we will look to reschedule them for next year. International collaborations are always difficult, but we were inspired by the knowledge that we would be able to present the work at a number of different venues, and the increase in the number of appearances means that the dancers can be paid accordingly. It also raises the quality of the work and allows the Theater to show the work it has produced to the world. The resulting international exchanges also increases the number of opportunities for us to collaborate on new projects, so there are a lot of advantages. - We would like to ask you now about your own career background. Could we begin by having you tell about your initial encounter with dance?

- From the age of five until age ten, I learned modern dance in Tokyo, and I entered contests and the like. In fact, both of my parents were originally competitors in apparatus gymnastics, and my mother was an Olympic hopeful (but retired from the sport after being injured in the qualifying stage). My father also did apparatus gymnastics and was an all-round athlete who also competed at the national level in skating and skiing, and also tennis and swimming, and a lot of my parents’ friends were Olympic athletes, so that was the kind of home environment I had. I also had athletic ability, but I was the kind of child who preferred to stay at home playing with dolls or baking cakes or making crafts rather than playing outdoors. With my parents’ expectations, I also studied at a gymnastics school, but I was too afraid to do acrobatics, so that didn’t last long.

After my mother retired from competitive gymnastics, she was studying to become a teacher of ordinary fitness gymnastics for the general public. In the process of following her around in the early days of aerobics and dance classes, I naturally became interested in dance. I still recall how impressed I was by dance performances I saw as a child, such as Russian ballet and Jun Kono and Keiko Takeya’s performance of Carmina Burana.

Looking back, I recall how much I liked dance as a child. For example I would always make up an original dance to perform at the monthly birthday parties in elementary school, and seeing that, my teacher asked me to try choreographing dances for the other students as well, and I ended up making dances for all of the students from 1st grade up to 5th grade.

Our family moved to Kumamoto (Kyushu) when I was in 4th grade of elementary school, but we couldn’t find a modern dance school there, so I entered the Kumamoto Ballet Kenkyujo school. In the modern dance school I had gone to in Tokyo, at the end of each day’s lesson the teacher would choose music for us to dance freely as we wanted, so I naturally felt that dance was something to express my body and emotions with. But with ballet, you of course had to learn set forms, which was very tiring for me (laughs). That started me on a time of wandering, I tried apparatus gymnastics again, I started skating, I entered the school’s drama club. In high school I took up rhythmic gymnastics. - You ended up going to Ochanomizu University where you studied dance and dance education in the Physical Education Department.

- I looked for a university where I could study dance and ended up choosing the only national 4-year university that had a major course with the name dance in it. It was primarily a course for training female physical education teachers, and at the time there was not as much importance placed on actual dance skills. So I also attended the Kikuko Moriya Modern Dance Studio that I had studied at as a child while also serving as a teaching assistant for the children’s classes of the dance school of my year’s dance professor Setsuko Ishiguro.

- You entered university in 1985, so it was a time when Japan’s contemporary dance scene was experiencing stimulating events like Pina Bausch and the Tanztheater Wuppertal’s first visit to Japan (1986) and Saburo Teshigawara won a prize at the Bagnolet International Choreography Competition (1986), wasn’t it?

- Yes, it was. That was everything. I was amazed to see dance like that. It was very important to have encountered such great things like that at a young age. At that time, rather than my own dance, it was the experience of seeing such powerful performances that probably connected to the work I am doing today as a producer.

At the university we would get information about was going on in dance, so I saw most of the important performances by artists like Pina Bausch, William Forsythe, Rosas, Saburo Teshigawara, Sankaijuku , Mika Kurosawa and others. One of the artists I especially liked was Kuniko Kisanuki. In my second year at university, I was incredibly impressed by the solo piece Tefutefu that I saw Kisanuki perform in a small room at the University of Tokyo arts fair, and after that I went to see almost all of her performances. - Kusanuki-san came from the modern dance genre and when she presented Tefutefu as an experimental piece in 1982 was a time when the term contemporary dance was seldom heard in Japan. She was a pioneer who led the movement toward new kinds of dance, and she performed overseas as well. As a professor at J.F. Oberlin University, she inspired many younger dancers there.

- I attended Kisanuki’s first dance workshop, as did Yoko Ando (later of the Forsythe Company). Among the dancers who debuted from Kisanuki-san’s company “neo” were Ando-san and Naoka Uemura (one year her junior at university) and Aki Nagatani. The third year after our theater opened, we planned a performance of Kisanuki-san’s solo production Karada no Machi (1994), and at that time she performed with Ando-san and Kenzo Kusuda.

There were many dancers of the generation as me in the latter half of the 1980s who emerged amid that first wave of contemporary dance. I happened to be among the participants in the first All Japan Dance Festival-KOBE that started in 1988 and remember a lot of talk about a very skillful dancer, Motoko Hirayama from University of Tsukuba. And it was from this same festival that Ryohei Kondo from Yokohama National University met dancers from other schools with whom he later formed the company CONDORS. Also, two years younger than us there was Akiko Kitamura (leader of Leni-Basso) and Chie Ito (leader of Strange Kinoko Dance Co. now by the name of Chieko Ito). Those are the dance companies started by these people that formed the core Japan’s contemporary dance scene in those days. - It was a generation that was inspired by from abroad and at home just in their most impressionable age. But isn’t it true that few of that generation turned to producing like you did?

- Perhaps so. At the time it wasn’t as if there was a direct route for people coming out of dance courses at university in Japan to become producers, and most public theater at the time were only operating on a leasing out facilities basis and weren’t doing productions of their own. To be honest, I didn’t know what to do career-wise so I decided to go on to graduate school and broaden my perspective by studying overseas dance.

- Were you not dancing any longer when you were in graduate school?

- I was still dancing. While studying post-modern dance in graduate school I became interested in collaborations with musicians and [visual] artists. That led me to doing improvisational performances in collaboration with musicians in site-specific spaces, and I was also working part-time at a contemporary art gallery in the Ginza district of Tokyo. When I was in graduate school, a work we created with four female dancers and four male musicians (including the stage music director with the Ishinha company, Kazuhisa Uchihashi) was invited to New York for a performance. That turned out to be the first festival experience of my life, and that amazing experience literally changed my life! At that time in Japan, dance was really only for a small group of dance fans, but I found in New York even elderly couples would enjoy coming to see dance together, and clearly the general public was enjoying the dance culture. And even for us, an unknown group coming from Japan, we got a full house at all five of our performances. People also came to our workshop and thanked us as they left. Those scenes all stayed fixed in my memory, and I was filled with the feeling that festivals like this were what I wanted to do.

So, I stayed in New York and went around to see a lot of places. Places like the Joyce Theater that I had hoped to see because of its famous dance programs, where I saw a Laura Dean performance, and listening to jazz at the famous jazz house Blue Note, going to Off Broadway plays and around the galleries in Soho. I also took classes and attended workshops by Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham, but the dancers that attended those classes were ones with talent so far beyond mine that it made me give up any ideas about choreographing and dancing my own pieces. I had fallen in love with the dance festival, but I still didn’t know what to do with that passion. So, I returned to Japan and started looking for a job. - At the time, Japan was at the height of its economic “bubble” and lots of performances were being brought to Japan from overseas, but there were still no dance festivals. In 1989, there was in Yokohama, however, the Yokohama Art Wave (*2) that would prove to be the first step in that direction.

- I went to see it and was very inspired by the fact that such an international dance festival was viable in Yokohama. Unfortunately, it was only held once, though, but the producer Maimi Sato went on to become a friend of some 30 years now and showed me the way toward what I really wanted to do.

After I returned to Japan from New York I was looking for a job even though I couldn’t find any image of what I wanted to do, and it was at that time that professor Yasuko Kataoka, who was serving as a work consultant at our university, showed me a recruitment notice for curators to work at the Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service of the Aichi Arts Center that was about to open and said, “Isn’t this the kind of job you are looking for?” The Arts Center had planned a performance by Sankaijuku (Butoh company) for its opening and a notice had come to our university saying that they were looking for someone knowledgeable in dance.

Until then, I had no connection whatsoever with Aichi, and I also had no qualification as a curator, but I was hired after I passed the Aichi prefectural civil service examination. Then, while working Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service, I took one year to get my qualification as a curator. So, from 1993 I was officially a curator. - Aichi Prefecture is the only place in Japan where a civil servant is employed as a dance curator. It was a new theater with a new type of organization and yours was a new position. Can we ask you to tell us about the Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service?

- The Aichi Arts Center is a comprehensive arts and culture facility consisting of the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater, the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service and the Aichi Prefectural Library. At the time of its opening, the entire facility was directly run by the Aichi prefectural government. The Art Theater was run primarily as a leased-out facility for outside productions of opera or theater with management by the Aichi Prefectural Cultural Promotion Corporation and at times with joint management by a local television station.

The main functions of the Arts Promotion Service where I worked were the gathering and dissemination of information about the arts and culture, and the Art Plaza section devoted to the gathering of arts-related information conducted research with the primary aim of providing programs (lectures, talks, workshops and experimental performances) to familiarize the citizenship with contemporary music, contemporary dance and experimental film/video and promote their spread. Instead of producing commercial type performances, it planned projects with methods closer to museology-based curation process. From one year before the Center’s opening, I was employed in the planning section, but the main program for the first year after the opening on October 30, 1992 had already been decided. - To commemorative opening performance at the Main Hall was Sankaijuku’s OMOTE – The Grazed Surface.

- That’s right. At the Arts Promotion Service, the overall theme was “the body.” And to embody the yearly themes from that first year until 2008 we had a talk and event called our “Eventalk” to expound on the theme. Today, such talk events are commonplace, but they were rare at that time, that first one we held was a discussion between Sankaijuku’s leader, Ushio Amagatsu and Seigo Matsuoka. And for a performance we got the dancer I respect so much, Kisanuki-san to perform. That was the first event I produced.

- On the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater website, you have your past programs produced by the Theater posted as an archive (*3). As for the Arts Promotion Service productions up until about 2002, you and the other curators have recorded the works carefully and with detail explanations. These records from before the spread of internet and its contents are especially precious.

- For most Japanese theaters, they have to work hard just to keep afloat financially, so keeping an archive is not one of their main priorities. But, for the Arts Promotion Service, fortunately the main mandate is gathering and disseminating information, so we have been able to keep an archive of well-recorded records. From the beginning, each curator in charge wrote their own planning and information documents and uploaded them on the website.

- In the following year, 1993, you had performances of Saburo Teshigawara’s NOIJECT.

- Beginning from Sankaijuku, I was in charge of the programs following our “body” and physical expression theme we had set. For both Sankaijuku and Teshigawara, it was their first time performing in Aichi, and we got a full house for both of them. But the first few years were a constant period of trial and error! I had just gotten out of university and had no experience in planning and executing programs at an arts and culture facility, and even though I had been hired as a civil servant specialized in dance, there were no precedents or models for me to follow. Among my seniors of the next older generation there were Maimi Sato (dance producer at Saitama Art Theater, Saitama Hall from 2005) and Mayumi Nagatoshi (President of An Creative Inc.), but both of them had experience and networks overseas in France and America respectively and they had been involved on a freelance basis at the theaters and festivals at that time. There were about 20 employees at our Arts Promotion Service, and even though I had a specialized job, I was still the youngest on the staff. Still, I was able to do the things I wanted if I got permission.

- At the Arts Promotion Service you had a “Human Collaboration” program from 1995 to’98.

- That was a comprehensive program that used all of the facilities of the Aichi Arts Center, connecting the Museum, Theater and the Arts Promotion Service and bringing an overall continuity to the program. For example, in 1995 we had the exhibition Circulating Currents – Japanese and Korean Contemporary Art at the Museum, and to accompany that we invited Korean Samul nori and Pansori performers and dancers and did a multidisciplinary collaboration with Japanese and Korean artists with music, dance and video works. Then in 1996 we had our Art Around Project Fune no Oka Mizu no Butai for which the poet Gozo Yoshimasu and our curators collaborated to write a script and composition and the video artist Hiroyuki Oki, dancers Mié Coquempot and Teru Goi and musician Tetsu Saito took part to create a 3-dimensional program that the audience wandered through in the area of the Center’s entrance. The experience of doing that crossover program would come to affect the production works I did later.

- Then you started your contemporary dance series in 1997. That program continued until 2002 and introduced artists from Japan and abroad in the genres of video and dance performances along with talks and workshops. From Japan you introduced a selection of representative artists from the younger generation like Kim Itoh , Sakiko Oshima +Motoko Hirayama, Akira Kasai +Mitsutake Kasai, Strange Kinoko Dance Co., Leni-Basso, Baneto and more.

- It was at a time when the term contemporary dance was just beginning to be recognized commonly in Japan. We didn’t have a lot of budget, but we were able to use the small hall of the Art Theater to introduce the new wave of Japanese dance in a ground-breaking program.

- At the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the opening of the Aichi Arts Center, the Arts Promotion Service produced a H.ART CHAOS dance work Carmina Burana Direction, choreography: Sakiko Oshima) with a full orchestra and chorus. I was very impressed by that. H.ART CHAOS is a large-scale dance company with a solid base in ballet and great expressive power, and you used the Main Hall of the theater with its more than 2,000 seating capacity and produced a work that brought out the full talent of the company’s dancers like never before. Audience gathered from Tokyo and other parts of Japan and the production was very well received.

- We were able to do it because of the added budget it was given as a commemorative anniversary production. Carmina Burana was a work of stage art that combined the three aspects of dance, song and live music performance with wonder effect that made you feel, “This is an all new form of opera!” It was this work that led to our “dance opera” series that started from the next year.

- I went to see your dance opera (*) productions every year. There was always such a variety of performers in combinations that truly surprised and excited us. In the end, even that great treasure of the ballet world, Farouk Ruzimatov performed in it.

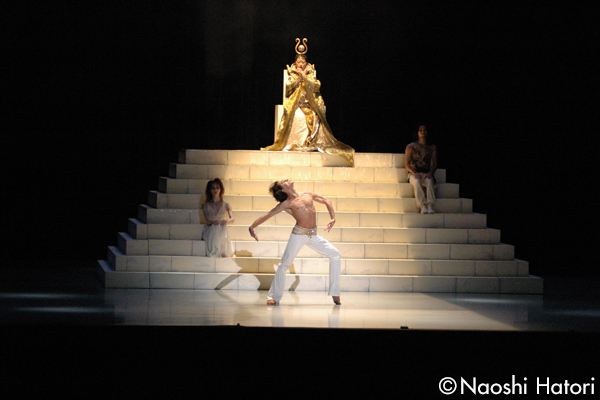

- Usually in opera the main focus is the singers and the conductor, but bringing in dance with its physical expression leveled the traditional hierarchy of opera to create a new era of opera as a composite art form, and it was my intention to propose a new type of opera with a strong dance element. We normally didn’t have a large enough budget to mount such productions, but it became possible when we got a 3-year grant from outside our own Center. Since we are a prefectural arts facility, it was hoped that we would focus on creation in collaboration with local arts organizations, so we made it a point to also link to the Aichi Dance festival and the local ballet company Dance Chronicle ~Sorezore no hakucho~ that could bring knowledge of ballet history to the planning of our productions. The dance opera UZME was created for the 2005 World Exposition, Aichi, Japan, and Akira Kasai did the choreography with Ruzimatov and Naoko Shirakawa performing as the dancers.

- Aichi Prefecture has a series of grand-scale events beginning with the 2005 World Exposition, Aichi, Japan and the 15th anniversary of the opening of the Aichi Prefectural Arts Center in 2007, and then followed by 1st Aichi Triennale in 2010. And especially notable is the way the Aichi Triennale placed a strong emphasis not only on the visual arts but also the performing arts.

- It was in large part the desire of the Aichi governor at the time to continue the success of the World Exposition with more large-scale arts and culture events that led to the launch of the Aichi Triennale. I served as the curator for the performing arts division for the first three Aichi Triennale holdings. Each time, it wasn’t until the last minute that the theme and the Artistic Director for the Triennale were chosen, which meant that I could only guess in what direction I should be planning and researching before each festival. When the decisions were finally made, it was very difficult to rapidly put my plans together. However, when they are in line with the festival’s theme, people are very happy to see innovative new works, and we were able to invite amazing works by overseas artists, even though they were unknown in Japan. Unlike festival directors overseas, there was also no guarantee that the works I suggested would be okayed, so all I could do was to propose works I wanted to have and could have in line with the given conditions and gradually make a place for contemporary dance within the overall program. My stance in curation was that if there wasn’t enough in the festival budget for the things I wanted, I would find sources of funding outside. In the process, I began to search out the possibilities for tie-ups with some of the small number of public theaters that also had contemporary dance programs.

From 2014, we shifted to a Designated Manager system of management, which brought a big change in our organizational format and the way we operated. Until this change, the Arts Promotion Service had been run directly by the Prefectural government, but with the organizational change, we were now run together with the Art Theater with the Aichi Prefectural Cultural Promotion Corporation as the Designated Management organization (while the video/film department came under the management of the Museum), and I took the new position as a producer for the Art Theater. Also, with the shift to the Designated Manager system, the organizational structure was revised, with the result that we could take a more systematic approach to the dance program. - What kinds of changes occurred as a result of the shift to the Designate Management system in specific terms? It appears that from then you also adopted community-oriented projects like the Family Program, didn’t you?

- It is the result of a major review and revision of programs following the passing of the “Law for the Activation of Theaters and Concert Halls (commonly referred to as the Theater Law) that went into effect in 2012, which was intended to stimulate the performance arts while also encouraging community programs. In the past, the Cultural Promotion Corporation had a budget for viewer arts like opera, theater and concerts, but the size of the budget was decreasing, and in the case of the Arts Promotion Service, before the shift to the Designated Manager system our budget had gotten so small that we needed to get outside funding for our programs.

When the Cultural Promotion Corporation assumed joint management of the Art Theater and the Arts Promotion Service, Yasuo Niwa was brought in as the new director (until 2019), and under his leadership a number of programs were re-examined. Director Niwa was formerly of the private-sector Nissay Theater in Tokyo, where he had experience initiating family-related programs, and in order to leverage the advantages of having the Art Theater facility to reach a wider audience, he initiated the Family Program and also school performances, to which local schools would be invited to bring their students. He also strengthened the relationships with public halls in cities and towns throughout the prefecture in order to plan a 10-venue tour of family programs invited from abroad in October 2019.

After Director Niwa’s arrival, we also began to have meetings once every two weeks at which we discussed things like what is really necessary in the different genres as part of the program planning process. I also made numerous proposals and was able for the first time to draw up medium- and long-term dance program plans to enable a systematic planning approach. Among the outcomes of this was the continuation of the Mini Theater Selection of experimental collaborations that I had engaged in from my time at the Arts Promotion Service. In addition to producing contemporary dance works like ARIKA, that I mentioned earlier, as well as Naoko Shirakawa’s Eternity (2016) with choreography by Sakiko Oshima, Kuniko Kato & Motoko Hirayama’s DOPE (2018) and others, I also invited in VerTeDance’s CORRECTION (2016) and circus-like performances such as murmures des murs (Victoria Thiérrée-Chaplin, 2015). Also, as part of the Mini Theater Selection, we started our Dance Selection that drew attention by presenting re-stagings of three existing dance works each over two days. We also did artist talks and workshops related to these works in order to increase understanding of dance and build our audience. Since there were so few critics in areas outside of Tokyo who could write about dance with authority, we had you, Mr. Norikoshi, come to give one of our review lectures. By the way, from last year we have started our Facilitator & Coordinator Human Resource Training Course. Through promotional and educational programs like these we hope we can build an environment for contemporary dance that hasn’t existed until now outside the main metropolitan centers like Tokyo. As a program that aims to present about ten performances a year, our Mini Theater Selection program had planned to present for the first time this May a production of Yoko Ando x Hana Sakai x Megumi Nakamura’s “Genealogy of Dance” in collaboration with the new performance space Dance Base Yokohama (DaBY), (unfortunately canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic). - Does the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater have a basic policy concerning dance programs?

- In the medium- and long-term plan adopted in 2016 as a program intended to make the best use of our facilities, we defined this as one of our programs focused on “presenting cutting-edge contemporary dance performances.” However, due to the limits of our budget and personnel, we continue to search for various ways to use the knowhow we have gained until now to work in collaboration with public theaters and festivals throughout Japan that have interest in contemporary dance to realize this mission.

The Art Theater has three halls that are used in different ways, with the Main Hall being used for things like invited productions from overseas that can be expected to draw large audiences and can be toured around Japan, while the Concert Hall is used for our dance concert series works done in collaboration with musicians, and the small hall is used for our Mini Theater Selection series. Still fresh in many people’s memories might be the Main Hall production of the first visit to Japan by the Netherlands Dance Theatre in 13 years (2019), and in recent years we have also hosted the Compania Nacional De Danza De Espana (The Spanish National Dance Company) at the Main Hall, as well as the Batsheva Dance Company and other invited productions. Based on careful examination over the year we have invited outstanding production of contemporary dance by such famous choreographers as Jiri Kylian, William Forsythe, Ohad Naharin, Crystal Pite, Marco Goecke and others. For programs at our Main Hall we have brought together ballet and contemporary for prime opportunities to broaden our audience base for dance.

In our 2019 dance concert series, we produced a production of Stars in Blue with such leading dancers as Manuel Legris where audiences can enjoy ballet and live music performance, and it toured to four venues, including the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre. Since our Aichi Prefectural Art Theater doesn’t have a medium-sized hall, for some productions we tie up with the public theater Nagoya City Performing Arts Center in Nagoya City (640 seats, managed by the Nagoya City Cultural Promotion Corporation). For the 3rd Aichi Triennale (2016) we also used that theater for a production of Ikinone choreographed by Un Yamada and for invited works of Rosas and Israel Galvan. As public theater is the same city of Nagoya we plan to jointly produce programs at a pace of about one work a year. - In 2020 it has been decided that Saburo Teshigawara will serve as Artistic Director of the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater. I don’t think there is any other case in Japan of an active contemporary dance artist assuming the position of Artistic Director of a public theater like yours.

- There are not any employees of a Japanese public theater who are specialized in dance, let alone an artistic director. Overseas there are many artists employed as civil servants, and there are also many artistic directors and producers who are employed as civil servants. With the appointment of Teshigawara-san, the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater will now be the first public theater in Japan to have both a dance-specialized artistic director and a producer as are seen overseas.

I have been talking repeatedly with Teshigawara-san since last year. And as he said at the press conference announcing his appointment as artistic director, I believe he will be involved in creating works with local dancers who have very high levels of physical skills, such those in the genre of ballet here in Aichi. Teshigawara-san has in the past done many collaborative productions with ballet companies overseas, so he has an outstanding network he can surely rely on. By the way, it has already been decided that to celebrate Teshigawara-san’s first year as Artistic Director our Mini Theater Selection series will feature Idiot (in July), The Human Essence Through Dance (in December) and a new play in February 2021. - Next we would like to ask you about the new Dance Base Yokohama (DaBY) that is the focus of so much attention right now. It has been founded by the SEGA SAMMY ARTS FOUNDATION and you will be serving as Artistic Director. And we hear that you will be doing that while also retaining your post as Senior Producer at the Aichi Prefectural Art theater. Would you tell us about how DaBY came to be established?

- It is not easy when you are employed as a civil servant as I am, but my position at DaBY is on a volunteer basis and I am able to hold both positions because the two organizations have kindly dealt with me on a very flexible basis. To begin with, SEGAMI SAMMY HOLDINGS INC. (*4) came to me several years ago with a request for advice about what would be the best area for them to support the arts in times like these. They wanted to know from among all the wide range of genres in the arts and culture, what would be the most meaningful area and method for support, and I suggested to them that it might be the most meaningful to support the genre that has received the least support until now. I suggested to them that in Japan that would be contemporary dance. Then I began taking their representative to a number of performances and theaters to see dance, and they understood why it would indeed be meaningful.

- In the founding principles of the Foundation, it says that, “Performing arts that are one-time events that can’t be reproduced are lacking in terms of productivity and are therefore chronically short of income,” and therefore support for them is especially meaningful.

- Yes. Overseas, dance is recognized as an important part of life and society. But in Japan, there are almost no dance professionals, even in the public theaters, and dance programs are few and limited. Although there are Japanese dancers who are active internationally, the life and professional environment surrounding them is quite severe. SEGA SAMMY’s president, Haruki Satomi has a lot of experience overseas, so he has no prejudices when it comes to dance or theater culture. So, when I proposed to him that for his entertainment company, “Art is the source of so many ideas that entertainment is built on. So, let’s take good care of and support that source!” he understood and agreed with my proposal.

Support can take many forms, such as establishing awards programs. But, until now I have seen many cases where awards are given to performing artists, but the grants are not ongoing. So, I proposed that we need a place shows an awareness that the support should go on for decades. And I proposed, “Please make a place that will serve as an anchor and base for dancers.” I was also bold enough to say that it needed to have a dance-dedicated theater and a dance company as well (laughs). - This interview is being held at the DaBY facility that is still under construction. The location is the Kitanaka Brick & White building that is connected to Bashamichi Station in Yokohama. This building is a Yokohama City Certified Historical Building that is a restoration of what was originally one of the old warehouses for the Yokohama thread inspection authority. It is a simple approx. 190 square meter space surrounded by the hallway of the archive area, and it has a very nice, unique atmosphere. It was scheduled to open on April 23rd (postponed because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic), and would you tell us how you plan to use it and under what kind of organizational structure?

- For 2020 we are thinking about some experimental programs. Basically, this is not a theater but a place for creating works and the funding for the facility and for the operating expenses comes from the Foundation. For example, we will give the artists several weeks for creation of a work here at DaBY for free and after that they will have a try-out performance for the local community to see. There are theaters in Japan that have facilities for creative work, but it is difficult to get time to use them for creative work. We will also be giving support for creation projects by a few young artists/groups a year. Since the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater doesn’t have facilities for the creation of works, I hope we can have tie-ups for creating works here in Yokohama to be performed in Aichi. We planned to have the try-out of the work “Genealogy of Dance” there in Yokohama as the facility’s opening commemorative event and then have the world premiere at the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater (postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic).

Also, I am often been told by Japanese dancers who have been performing overseas that there is no place for them when they come back to Japan, and there is no one for them to consult with. I hope that DaBY can become a place where artist who are performing in different genres and living in different areas can connect to each other. Since the Kitanaka Brick & White has a good number of commercial facilities, we hope we can use those creation spaces to create opportunities for the customers to relate to dance more easily. - The “Genealogy of Dance” is a unique program intended to explore the origins of choreography by beginning with dance classics and then attempt “the succession and reconstruction of choreography by having the same dancers newly choreograph pieces.

- Since this was intended as our first production at DaBY as a place for professional “dance,” we planned a program to focus on choreography as the origin of dance. We want it to be an opportunity for the dancers and the audience to deepen their understanding of the history of dance. Also, we want new forms of expression to emerge from this program, so we adopted a format in which works by famous international choreographers and experimental works will also be presented. As a result, we have scheduled ambitious works like one in which Toshiki Okada of Chelfitsch has Hana Sakai choreograph for The Dying Swan.

- Some of the well-known public facilities in Japan that provide support for performing artists are the Kinosaki International Arts Center, which offers free long-term residencies, and the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM) , which offers the strong support of resident technical staff. Meanwhile, as a new movement in recent years, we find active artists like Megumi Nakamura , Hiroaki Umeda , Shintaro Hirahara and Ryu Suzuki are independently offering seminars for dancers and choreographers.

- I believe that providing dancers and choreographers with opportunities to study and receive support are very important issues. At DaBY, we have a “Dance Evangelist” post that has been given to Kenta Kojiri. He has a wealth of experience overseas at places like the Netherlands Dance Theatre, so we hope he can serve as a mentor for young Japanese dancers capable of providing consultation and assistance in their creative activities. Furthermore, I hope he can serve an important role in connecting audience and the general public to DaBY and to dance in general. To begin with, we plan to hold classes for dancers chosen by audition (postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic) who aim to become professional dancers.

I also feel that strengthening the employment environment for dancers is an urgent issue, so we have appointed a legal advisor to offer counseling for things like employment contracts. That person is Chihiro Tokai, a lawyer in her 30s who loves ballet. Usually, dancers are the lowest paid of all the staff involved in performances, and their position is the weakest, so in many cases they don’t even have a contract. And if they do have one it is one that benefits the employer most. We plan to make a model contract at DaBY that we can offer for dancers to use along with advice about the content of the contracts they sign.

Also, beyond dance-related cases, we plan to offer a program of study seminars that can teach a range of knowledge that artists should have in legal and societal matters, including how to write grant applications, things related to lighting and music and the like. We have a number of creators from various fields such as architects and designers who will be working with us. If possible I also want to create opportunities for experimentation by young people in the areas related to dance such as musicians, stage art creators and costume designers. I believe that having crossover projects with people from a variety of genres will help bring greater richness to the dance world. - In Japan’s arts education system, there are few places or theaters where people can study dance specifically, so it seems that there is still a lot that has to be done to strengthen the environment for promoting the development dance.

- Yes. There are so many issues that it is hard to know where to even begin, but I believe that when considering the present situation in Japan, the most important job is to grow the audience for dance. If that audience grows in numbers, more theaters will undertake dance programs and that will help improve the environment for dancer activity little by little. At the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater we use our large and small halls for specific purposes; the works we present at our small hall can help build core fans by bringing the artists doing experimental work together in a close relationship with the audience, while the works we present at our large hall can serve the purpose of bringing large numbers of audience to the entrance of dance performances. Together, these two programs can contribute in different ways to the task of building audience.

Meanwhile, DaBY is not a theater but a place for the creation of works. This means it is a place where the artists spend much more of their working time compared to the time they spend performing at the theater. In Japan the theater and daily life are separate realms, and the threshold that we have to get people to cross to even enter a theater is still very high. As something one step short of getting people into the theater, I think giving people easy access to the place where they can watch the dancers at work can help lower that threshold to getting people to take that first step into the theater and see dance. So I want us to use this as another way to grow our audience.

In either case, building audience is something that has to be undertaken with a long-term approach. I am fortunate to be employed as a civil servant specialized in dance, so I feel that I must devote my professional life to Aichi Prefecture for that, but it is nearly impossible for staff at a theater that is currently managed under the Designated Management system or at a public culture and arts facility run by local government to plan and operate with a middle- to long-term vision. In order to bring fundamental change to the present environment and build one that can support and promote the development of dance, I believe that there is a real need to look again and revise the institutional aspects of the system and make organizational changes such as employing specialized professionals and bringing systematic change to the management systems.

From an athletic family background into the world of dance

A life-changing first festival experience

Programs at the Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service

Self-production at the Aichi Art Center and the birth of “dance opera”

Expanding the contemporary dance program with a new organizational structure

A new Dance base, DaBY in Yokohama

The Aichi Arts Center

Opened 1992. From 2010 it has been the main venue for the Aichi Triennale with its facilities including Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, the Aichi Prefectural Art Theater with its Main Theater (max. 2,480 seats) capable of holding full-fledged opera and ballet productions, a Concert Hall (max.1800 seats) and a Mini Theater (max.330 seats), and its Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service consisting of the Art Space, Art Library and Art Plaza. At the time of its opening, the entire facility was directly run by the Aichi prefectural government, except for Art Theater, which was entrusted to the management of the Aichi Prefectural Cultural Promotion Corporation (a public interest incorporated foundation since 2012). From 2014, the Art Theater and Aichi Prefectural Arts Promotion Service (except the Art Library) all came under the management of the Cultural Promotion Corporation. Prior to this consolidation, the Arts Promotion Service had one curator each for the music, video and dance departments.

https://www.aac.pref.aichi.jp/