- Seventeen years have passed since you started your company [H. Art Chaos] in 1989. Can you tell us how you came to create the company? Your focus was mainly from ballet and modern dance, I believe, but I hear that you also had an interest in theater.

- I don’t have any background in theater, except for the fact that I was in the theater club at my junior high school and I wrote a play or two at that time. In college I was in the advertising study club, but I was interested in dance and theater and often went to performances and eventually entered the company of Kimio Nosaka, who is presently the leader of the Dance Works company. There I learned the fundamentals of modern dance technique, and I also used to go for lessons at Ayako Ogawa’s open ballet classes. As I was doing that I gradually got a vague desire to create works of my own, works that based on a world that I wanted to see. It was just about that time that Naoko Shirakawa joined Nosaka’s company.

- So, that was when you met Ms. Shirakawa, whom you have been working with for 17 years now in H. Art Chaos?

- Yes. From the first time I saw her, Shirakawa had an aura that other people just didn’t have. Normally she is very candid and natural and easy to get along with, but the moment she starts dancing she projects a completely different aura. Everyone changes somehow when they get up on a stage, but even in rehearsals she just switches into a different mode. Mr. Nosaka also used to say that she was a dance with tremendous potential. So, I knew that when I started a company I had to have Shirakawa and I was determined to build a world of dance around her presence. And, in fact that was the types of works I choreographed, so I think you could say that there would have been no company without her.

- How did you arrive at the company name H. Art Chaos?

- H. is for heaven, Art is art and Chaos is disorder. The heaven of H. is English but the Art is the French pronunciation art. Chaos is Greek in image. It is a name that expresses the conviction that our activities have to transcend the boundaries of nation, race and language and also that we have to transcend the boundaries of our self in activities that will reach out to communicate with others. It also implies the desire to share with audiences the transcendental state in which heaven is born out of chaos.

- That company name seems to be a perfect expression of the kinds of works you are creating. Was the company an all-woman company from the beginning?

-

It wasn’t as if that was the intention from the start, but it is a fact that all 12 or 13 dancers we started out with were women. But Shirakawa is the kind of dancer who projects both female and male characteristics, and in fact there were numerous works in our early years that had male dancers in them too. Also, when I do choreography for other companies today it is often for male dancers.

When you think about what it is to be a man or to be a woman, I believe that you will be giving the audience a larger framework of imaginative possibilities if you concentrate on just one gender or the other. I also think that I feel this way because of the person or presence Shirakawa is. I feel that by using only men or only women you are giving the audience more of an opportunity to transcend the mundane and envision things freely. When you use only one gender, I feel that it makes the social and interpersonal restrictions associated with the body more abstract because they are less directly felt and it is easier to transcend the preconceptions associated with gender. I believe that it is also effective when trying to express some type of religious state of mind. I feel that when you transcend gender the body becomes a more noble presence. - In other words “gender” becomes “the sacred”?

- Yes. I believe that it is easier to get that type of potential when you are working with a single gender. Of course, at times when that is not the main aim it will expand the richness of expressive possibilities if we include male dancers as well. I had some sense of this type of dynamic in 1989 when we first started out, but I wouldn’t have been able to express in words like these at that time. It was a feeling that came to me gradually and by the time of the work Himitsu Kurabu … Fuyu Suru Tenshitachi (Secret Club … Floating Angels) (1992) it was clear to me.

- In all of your works you use space so skillfully and create such a large scale to them. You also seem to have such a clear image of stage art as well.

-

I plan almost all the stage art for our productions by myself. As I am choreographing a piece I am also thinking about the lighting. The music is also a highly integral part of the work and because of the mutual effect of the music and lighting there is no room for even a moment’s discrepancy in the operation. Lighting is the process of creating art with light. It must be extremely exacting, in terms of things like what percentage you make the light fade to in how many seconds. If you have a dancer suspended from a wire and moving through the air, it will have a completely different effect if the dancer appears to be moving forward into the light as opposed to having the light make the dancer appear in silhouette. These are the things I am thinking about in detail as I work.

As with light, there is also reason and intent in darkness. In darkness there is an image of complete nothingness, a form of zero state in which all pluses and minuses are in perfect balance. Since it can be developed into things like time or space or life and death and other philosophical themes, the darkness I seek in stage lighting has color nuances. In this way, lighting carries great importance in my works. The power of light is as important as the fact that there are bodies in this world. Maybe it is something even more amazing. - You often have dancers suspended from wires in your works.

- When I use wires it is not to express the freedom of flying but because I want to express the process of being pulled back to reality after flight. When suspended in air by wires, a dancer’s body can become very free, but the wire also brings a negative aspect of restriction. It is not something that can free us from gravity but simply changes the way gravity acts on the body. This is what can make one raw body stand out in a work and why devices like wires and rubber are very effective things for me to use. But it is only as a means of expanding human potential.

- In creating your works, are the collaborative efforts with a dancer Shirakawa important?

- Of course it is important. You might say that the body breaks down the things we conceive in our heads and brings them back to reality. Shirakawa’s body breaks apart my images. But I believe that it is necessary to dismantle things produced in the left hemisphere of the brain through the processes of reason once. I am often stimulated by words and create ideas for works based on them round which I try to create a new world. When creating a work, however, I believe that the words themselves have to be broken down and dissected once. And I think that it is only the body that can do this. If you use the body to break down meaning again and again as far as you can, then I find that it is possible to rebuild your concept.

- The themes are very philosophical and social, and when you add your spatial effects, the works you create have a grand-scale aspect of the universe and its workings.

-

For a long time I have had a great interest in philosophical themes like “time” and “human character” and “life and death” and the make-up of the universe. I have long been attracted to the romance in the philosophical works of Heisenberg and Schrodinger and quantum mechanics after Einstein. I also love the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Wittgenstein and Derrida for what they say about the individual’s relationship to the world and Merleau-Ponty for the things he proposes about the relationship of the body to the world. Taking the theme of the limitless creative potential harbored in the energy of living things that Henri Bergson calls “elan vital” in his book

Creative Evolution

, I created a work titled Elan Vital – The Manic Depression of Eve (premiere 2002) with the theme of ES cells and cloning and other things that blur the borderline at the start of life.

Concerning space, what I think about most is that it is the body that gives spaces their presence more than anything else. Spaces are born because there is a body and so, I believe a space can exist that has the body as its center. We live in a world today where things are changing so fast that it is hard to keep up with the changes. Therefore, I feel that in directing a stage performance, if I can create a moment when the potential of the body is expanded to some degree in a human way, that is the moment when the true power, the awesome potential of the raw body emerges. We don’t have wings but we can fly in airplanes. We don’t need to use a big voice because we have microphones, we can speak to people far away by telephone and we now have the capacity to record information outside of our brains. In these ways, we are expanding and extending our bodies out into external spaces even in everyday life. That is why I feel that in the space of the stage I want to create a body-centric space in which the surroundings, including the props and such, become a space flowing with energy, a space that dances with the body. Within this context, I feel that there is more reality to the raw body in moments when its potential is altered or expanded and it is possible to regain the sense of reality to the world that often becomes lost. - You incorporated Saussure’s theory of symbol in the title of your 1993 work Signifiant et signifié – Little Mermaid . This became an important work at a time about four years after the company was established and you were beginning to become noticed.

- The little Mermaid leaves the sea at the age of 17 and I got the idea that I wanted to create a visual expression of a body in the stage space as a symbol specifically of a woman come of age. This was a work that I created while thinking about ideas like having a body that was there a minute ago remain only as an outline by using such devices as a two-level stage divided between an upper and lower level.

- I feel that in your work Swan Lake – Writing Degree Zero (premiere 1994) you showed yet another approach to the body.

- That was a work in which I wanted to dissect the social meanings that a woman’s body is saddled with. At the time there was a social phenomenon known as “ burusera shops” that sold school uniforms or underwear that junior and senior high school girls had worn to the shop in order to sell. It was that problem that got me to focus on the sex industry. I had the dancers remove one pair of panties after another as they danced until there was a lake of panties. Wearing about ten pairs of panties each, the dancers dance on joyfully unaware of the discarded panties on the ground, but eventually the panties under foot cause them to lose their footing. I saw high school girls interviewed on a TV documentary saying, “What’s wrong with selling them, as long as it doesn’t hurt anyone.” Watching them, I got the feeling that I was watching swans plucking out their own feathers. In what was spewing out of the bodies of these girls, I felt that I was seeing some form of punishment being visited on the body by our times.

- In your representative work the Rite of Spring (premiere 1995) there also seems to be an aspect of sharp social criticism. I don’t know if you have an aversion to expressions like the “position of women in society” but I feel that there is clearly a feminist perspective in the work.

- That was a work in which I tried to choreograph something that might be called the “violence of the eye” or “the violence of the viewer” while following the contents of the music in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring . I was thinking about not the violence of the perpetrator against the victim but the violence of the innocent bystander, the sacrificial victims that the times choose unconsciously. At the time in Japan, a lot of attention was focused on the problem of bullying, and just after I did this work Princess Diana died in a crash while being pursued by paparazzi. I did that work because I was feeling what you might call a fear of our lack of consciousness of that type of “the violence of the viewer,” and I was thinking that perhaps society was experiencing an outpouring the anxiety or frustration that can build up in our bodies without our being aware of it.

- Shirakawa’s presence and dancing were especially wonderful in that work. I also felt that your use of wires in that work reached a new level of effectiveness, such as the use of wire-suspended chairs.

- I hadn’t thought of that before, but now that you mention it, perhaps that is true. The dancers are just standing and watch as the chairs spin in the air around them. The eye, the line of sight that we feel at that moment is almost tactile. Why is that, what is it about that eye, that act of watching. I think of it as a kind of touch from a distance. When we feel the cold or critical stares of people from a distance, we can almost sense those eyes on our skin. I tried to express that eye of the viewer using the chairs floating in the air and chairs being thrown. The eye can be a kind of weapon, and I believe that it can be a pressing form of violence against a victim.

- In terms of Shirakawa’s presence, she was also magnificent in Romeo and Juliet (premiere 1996). This was a solo work for her, but we got the impression that many people had appeared in the dance.

- Romeo and Juliet can be considered a tragedy caused by a failure of communication, when the Friar’s letter fails to be delivered to Romeo. I took that as the point of departure to create a work that takes place in the world of computers. We only live one life but something like a video can be reset and played over and over. So, I made Juliet a game character that is brought back to life repeatedly, but at one point a virus causes a failure of the software that makes it impossible to reset, so the character is suddenly confronted with the sadness of only being able to live and die once. I wanted to use this device to create a renewed recognition of the compelling fact of life as a one-time affair and to portray sadness as one of time’s antics.

- Your work Nemuri no Mori no —— (House of Sleeping…)(premiere 1997) which took its motif from Yasunari Kawabata’s Nemureru Bijo (House of Sleeping Beauties) and the original Sleeping Beauty was performed in an outdoor venue (Yokohama Business Park, Mizu no Hall).

- When I saw the location with its pool of water in a somehow fantasy-like corridor with the modern buildings of the city in the distance, I had a vision of a lake in the middle of a forest. I though that in a place like this I could do a work that suggested that perhaps all the people working in this forest of skyscrapers were actually living in a sleeping world. There is a strange form of eroticism in Kawabata’s work. It made me think about what could cause the main character to wish for a relationship that was not sexual but merely a desire to lie beside a sleeping young woman, who in that unconscious state was something close to a corpse. Wouldn’t it be possible to release something precious that people are blind to as they live their half-sleeping lives in the city? I began working on this piece with a concept close to necrophilia, where young beauties lying on beds in an unconscious state almost like corpses are carried forth from out of the sparkling water. I created this work with the idea constantly in mind that sleep in the younger brother of death and a lesson to prepare for death.

- You toured North America in 2000 with your work Himitsu Kurabu … Fuyu Suru Tenshitachi (Secret Club … Floating Angels) and got excellent reviews, including one by Anna Kisselgoff. This is one of your original works first performed in 1992 (remake in 1998) that might be considered the roots of your company. It makes use of wire work, group dances and Shirakawa solos, mirrors and flashlights, and darkness as an element of lighting.

- This was one of my earlier works and one that just seemed to complete itself before I knew it. The theme was the idea that true objectivity is in fact impossible in this world. Since the world that a fly sees is different from the world that we humans see, I believe that we can never know what the real world is. Subjectivity and objectivity may be just different layers of worlds that are seen differently, and there may be no real boundary between madness and sanity. So, the world seen by one consciousness is actually something that is full of secrets that other people can never see.

- I have heard that your work from 2001 comes from a personal experience of life and death.

-

I was drowning in the sea in Bali and the moment I though, “Oh no, I’m going to die,” the purplish blue water and the swaying seaweed seemed to become perfectly still and I had the feeling that time had stopped. I completely lost consciousness after that. It turned out to be nothing serious and when I saw a flower on the beach after I regained consciousness, I had a sense that I could see time moving inside the flower. That was quite a shocking experience for me. I got the feeling then that there is time in this world and being alive means having time in your body. In other words, I had a strong feeling that in one sense this world is a world that is given expression by time.

When thinking about death, we used to think that it must be god that decides the moment of death, but now human beings have reached the point where we can operate an artificial breathing machine and push back the moment of death with life-support systems. The borderline between life and death has now become blurred to the point that what used to be the realm of god is now something that involves a person’s family. Since the body that used to be one’s can now be invaded by the organs of other people, like in the case of a heart transplant, the boundaries of the body are now blurring, just like the borderline between life and death is blurring. Kamigami wo Tsukuru Kikai (The Machine that Makes Gods) is the work I created while thinking about what the body is in an age like this when the body is subject to fluctuating ethical questions of life and death. - It seems that this theme continues in your work with Bokyaku to iu Shinwa (Myth Called Forgetting) (premiere 2003) and Jinko Rakuen (Artificial Paradise) (premiere 2004) in which the images of life and death are played out in the real and the virtual.

- Myth Called Forgetting is a work about the time of individuals who are forgotten in the flow of history. With Artificial Paradise and Byakuya (Midnight Sun) I thought quite a lot about the virtual. In Artificial Paradise the theme is the image of our bodies in this world where time and place are always edited. What I thought about with Midnight Sun was the security cameras in shopping center. My image is taken at one-second intervals and those images of time gone by are compiled. It has become commonplace now for us to be constantly observed in this way. In this world that tries to control everything, information like your blood type is being compiled at outside sources without our knowing it, the national government is trying to put numbers on everyone, and I think that within this process our sense of the body is changing greatly. Regardless of whether you are aware of it or not, everything is being recorded in computers. Our culture has been created through the excesses of the body and it surprises me how now it seems that those excesses are coming back into our bodies in different forms. The security lock on my house is a fingerprint-reading type and I do the operation without a thought, but when you think about it, I say “What is going on here?” As cell phones and computer security locks also come to be biologically based, our bodies become living keys. Without our realizing it, the body becomes a virtual entity that is being spread around to all sorts of places. But, since we are not actually using the body at all in these operations, they become fragmented experiences for the body itself. The body’s existence is not here in its physical form but being manipulated as information inside of machines…. So I thought, that virtual space is not off in some unknown place but is always right here with us.

- In recent years you are working actively not only with your company but also as an independent choreographer. You have now done your second choreography work for the Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT).

-

In 2001, we did an H. Art Chaos performance of the

Rite of Spring

at the Singapore Arts Festival. The SDT artistic director, Ms. Goh Soo Khim, saw our performance and asked me to choreograph a piece for their company. The first collaborative work we did with them was

Feast of Immortality

in 2003.

I had The Machine that Makes Gods as the basic piece to work from, and the theme, the set and the music were all the same. Since I was choreographing for a ballet company, I used a lot of pointe when I reworked the piece for SDT. I used all 24 of the company’s dancers, including the men. I used wires, I used pointe and I included a new scene for the men. Since the pointe used in ballet is completely different from what we use in H. Art Chaos, the choreography and composition of the work was completely different in the SDT version, to the point that it became a completely different work. - I recall that Shirakawa danced the lead of Feast of Immortality , but in this new work Whose Voice Cries Out? it appears to be a complete original using only SDT dancers. I saw the performance at the Esplanade on August 31 and I found it to be a marvelous work that made good use of the strengths of the ballet company.

- We did the work in two separate sessions and that seems to have worked out well. First I stayed in Singapore in June and held a workshop for three weeks. We did improvisational movement and we did theatrical type exercises where I had them using their voices all the time. We tried a variety of things like seeing if they could carry out their movements while screaming into a microphone. That was all quite interesting in itself but there were also a lot of aspects that turned out to be different from what I had in mind originally. At that point my ideas had become rather fragmented. Then in July I returned to Japan and rethought things after I’d let it all settle. I did a lot of research about pointe play. Since I was starting from scratch, I knew how I had to move the choreographing and everything along if I was going to finish the piece in time. I used Shirakawa to work out each of the parts at time, but I can tell you that it was really a mess at the beginning.

- How did you come up with the concept? Did you use aspects of Singaporean society as motifs?

-

I had been quite inspired by the dancers in the company while I was doing the workshop in June. Singapore is and advanced IT society where Internet use is high, but compared to Tokyo there is still much stronger connection between people and with the natural environment. Since Singapore has a variety of ethnic groups, I feel that the people there think a lot more about their relationship with others. I felt that their interpersonal relationships were something that was complete different and much deeper than those in the world of the Internet.

In fact I did a lot of choosing of choreographic moves and got valuable feedback from the dancers, and we all worked very hard. Still, the way they danced moves that we commonly use in H. Art Chaos was completely different. When I would say, “Try breathing at this point,” it just wouldn’t get through to them as I expected, and they would interpret what I wanted in terms of the dance movement quite differently. At times it came out to be a completely different dance from what I had choreographed. There was none of the responses that one expects naturally with one’s own company. And thinking about this communication and miscommunication became a theme of this production. - In other words, it became a work that only could have happened in Singapore?

-

I thought about the isolation and solitude of times like ours when time and distances are all edited. The scene where only the dancers head poke out through boards is a representation of a state where the true self is lost because of repression. We can learn everything about places far away thanks to the Internet or TV but we know nothing about the people living next door. Hasn’t that become our everyday sensibility? My theme is the relationships of people today that involve a lack of actual physical experience, or fragmented physical experiences involving mostly the parts from the neck up, like being next to a person but they are talking to someone far away by cell phone.

The images on the TV can work their way into your head unknown to you and when you give an opinion about something it actually turns out that you are just repeating an opinion that you heard a TV announcer give. You find people looking at a woman (or man) as if they are looking at a product, or both women and men may look that way. When you are reading a book you may suddenly get the feeling that it is not you reading the book but the book telling a story inside your head …. Or the feeling that your head alone is of somewhere creating your world all by itself. These are the kinds of uncomfortable feelings that are the motif in this work. - Will you continue to work with this company?

- I am not sure, but I will say that I was surprised at how different it was to work with them even in the choreographing aspect. Since they are a ballet company and composed of people from a variety of different ethnic backgrounds, I felt like I was in the New York of Asia. There were dancers who would be asleep in the rehearsal studio, there would others who were trying hard to understand my Japanese, and the attitudes would vary with the race and the individual. Usually you expect to see the people of the same company sharing a common attitude. But, for better or worse, there is certainly a lot of variety here [in Singapore]. Japan is a mono-ethnic country, so this was a very interesting experience for me.

- What about the future?

- Next February I am going to direct and choreograph an opera production with the Nikikai in Tokyo. The work we will be doing is the oldest known opera, Daphne from the Greek myths, with music by Richard Strauss. Of course, Shrakawa will be dancing in it. It will be another new challenge.

Sakiko Oshima

The unique aesthetic art world of director and choreographer Sakiko Oshima

Sakiko Oshima

Sakiko Oshima is a director and choreographer. In 1989 she formed the dance company H. Art Chaos with dancer Naoko Shirakawa. A unique aesthetic sensibility and philosophy has helped make it one of Japan’s top companies, highly acclaimed both at home and abroad. Oshima’s work has included grand-scale productions such as the Rite of Spring with a 100-person orchestra and a production of Carmina Brana with orchestra, chorus and opera singers. With numerous invitations from overseas arts festivals, Oshima has presented works in many cities in Japan and abroad. On her company’s second North American tour in 2000, following their first in 1997, the New York Times chose their performance for its “Dance of the Year” award, and in 2002 she was awarded the Asahi Performing Arts Award. These are just some of the international and domestic awards to her credit. In June of 2003 Oshima directed and choreographed a production (danced by Shirakawa) with the Singapore ballet company Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT). In 2004 the production toured Stravinsky’s birthplace, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Helsinki and Warsaw. In September of this year she premiered a new work Whose Voice Cries Out? with SDT. In February of 2007 she will direct the opera Daphne produced by Tokyo Nikikai.

Interviewer: Akiko Tachiki / interviewed at Singapore’s Esplanade Theatre on Sept. 2, 2006, during the run of Whose Voice Cries Out?

Signifiant et signifié – Little Mermaid

Photo (c) Arata Yoshimura

Swan Lake – Writing Degree Zero

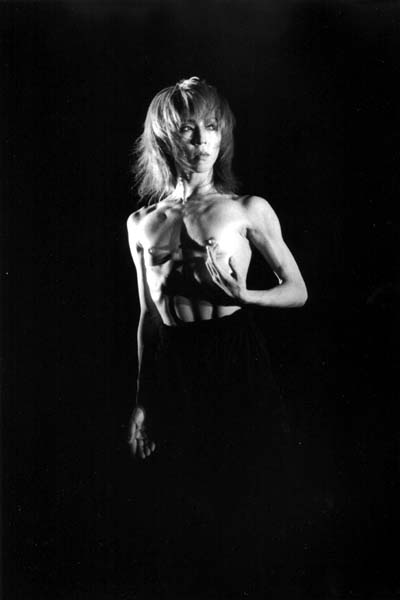

The Rite of Spring

Photo (c) Etsuko Matsuyama

Romeo and Juliet

Photo (c) inri

House of Sleeping…

Photo (c) Naoki Takeda

Secret Club … Floating Angels

Photo (c) Akira Shikano

The Machine that Makes Gods 2005

Photo (c) Etsuko Matsuyama

Artificial Paradise

Photo (c) Sakae Oguma

Midnight Sun

Photo (c) Sakae Oguma

H.ART CHAOS & Singapore Dance Theatre

Feast of Immortality

Singapore Dance Theatre

Whose Voice Cries Out?