RAM: Projecting human motion into performance spaces

- I have been to a RAM workshop and seen how the movements of a person wearing a motion-capture suit are modeled into a human-shaped wire frame and recreated in real-time on a monitor screen, and how the wire-frame human form can be made to hold something like a long pole, or how it can be shown as if surrounded by a transparent square box, or be modeled freely into other non-human forms. It begins with the person in the motion-capture suit moving the wire-frame figure’s image, but in time the movement of the figure begins to affect the movement of the actual person moving it. I was given the opportunity to try wearing the suit and moving the image, and as I did I began wondering how a dance would use it for creating a new dance piece. Would you begin by telling us how the RAM project began?

-

It started in 2010, when Yoko Ando, who had come to participate in a different project using video visuals, came to us on her own and said that she was interested to see what she would look like using the system and wanted to try it once. She had experience of video images of herself in motion being shown in video monitors in real-time, but she said she thought it would be interesting if it could be taken one step further so that her image was able to move around and touch rectangular icons appearing in the monitor, and I told her, “We can do that!” It also turned out that the timing happened to be good in terms of scheduling, so that became the start of what would be her period of experimentation and fun working with the members of our InterLab. The prospect of things that are happening in the monitor and the movement of a human figure interacting and affecting each other was so interesting that the curator Kazunao Abe proposed that we create an exhibition piece using this concept. Ando-san used her vacation days from The Forsythe Company to come three or four times to work with us for three days to a week at a time on the project. The product of this research and development was the work that Ando introduced in her new installation work “Reacting Space for Dividual Behavior” in May of 2011. For this production we used ten units of the Microsoft “KINECT” 3D camera used in game development and a space surrounded by 23 video monitors where participants could touch objects in the resulting virtual space and see them make sounds and change colors and moved them around. On the opening day of the exhibition, Ando-san used this system to do a solo dance demonstration.Many people enjoyed that exhibition, but more than that was the great number of ideas for new things to experiment with that came out of this experience. But, in order to experiment with a variety of other new ideas, I had a sense that we would need motion capture equipment with some degree of stability in performance and precision. When we tried using motion capture images from KINECT camera in exhibitions, we also found that they weren’t much use, at least in terms of the new things we wanted to do at the time. So, we went around to dealers that were handling motion capture equipment, and what we found was that the equipment that was generally being used in the film or game production industries were prohibitively expensive for us. So we began to ask whether or not we couldn’t develop the equipment we wanted by ourselves.

- Did you think you could develop it?

- We did (laughs). We knew it would be impossible for us to equal the performance of the high-priced equipment, but we thought that it would be possible for use to develop something that met the minimum performance requirement for the types of things we wanted to experiment with.

Most of the [high-quality] motion capture equipment on the market basically had the performance capability to gather the vast amounts of high-precision data output for motion generated with the right set-up and specially designed [sensor] suits. But, we estimated that even without that kind of high level of performance, there was still a lot of things that we could do, and since we had taken as a prerequisite the use of an open-source system for the output, we were hoping that we could find the components we needed at a fairly reasonable price. So, with the idea of creating systems that could give us the output we needed on physical motion as inexpensively as possible, we decided to use the kind of inertial [motion] sensors that are used in smartphones. We thought that if we attached those inertial sensors to the necessary places on the body and applied their reading to a human-form model, we could probably do effective modeling of human motion in a computer. However, while this would give us data about changed in the attitude of the body’s parts, it would not give us data to calculate the body’s position in a space—for example where the dance is on the stage floor. And for the same reason, this system has a number of limitations, such as in inability to register something like a jump by a dancer, since it is not capable of recording movement in the vertical direction, etc. From there, we worked on research and development of our system for about one year, from March of 2012 to February of 2013, and then we unveiled it along with some other things like software kits.We also rented some very expensive, top-end motion capture equipment a few times with the help of a sponsor and did some experiments that could only be done with it. It was optical type equipment and we used it in a set-up with more than ten cameras placed around the perimeter of the dance area. By attaching small white balls called markers to the [dancers’] bodies, we were able to get data about the changes in body attitude and position to an accuracy of within a few millimeters. There were some disadvantages involved, such as the stress on the dancers caused by having to wear the special suit, which was distracting visually and looked uncomfortable as well, but the response was excellent and for me it was very enjoyable to work on.Around the summer of 2012, there was a time when we did a test that involved dancing with a pair of poles to which we attached those motion-capture markers. We displayed a Bezier curve to connect the two poles with curved lines in the screen. We had Yasutake Shimaji, who was a member of The Forsythe Company at the time, dance with the poles in his two hands while watching the resulting motion of the curved lines in the monitor, and when we used the computer to adjust the firmness of the curves being generated, it caused a change in the motions of the actual dancer, Shimaji. In short, the visual feedback from watching the monitor as the firmness of curves were adjusted, from loose curves that gave the motion a feeling like that of a jump rope being swung to firmer curves that gave the motion a feeling like that of a thin strip of bamboo being flexed, naturally caused changes in the feeling of the dancer and his actual movements. Seeing that made me feel that it might be possible to do a variety of interesting things by making skillful use of the sensors and real-time visual feedback from the resulting images generated on the screen.Eventually we came to refer to this kind of a environment set up to generate curves on a monitor as “scenes,” but since we still didn’t know at the time what kind of environment could be connected to dancer’s movement with interesting results, the different members of our group started making a variety of them as ideas came to mind, and then we began to work with Ando-san to refine them. Until now, we have created quite a large number of these “scene” set-ups, including ones for workshops, and what is interesting is that we find now that, even though there is no particular system we are working from, we are able to intuitively recall the things that we have had some experience using with the RAM system and recreate a similar scene to use again. I believe that it is fundamentally the same as the ability to the way the body remembers things that it has experienced or been trained to do, and we got excited about the prospect that the programs that we had created were virtually being “installed” in people’s heads [like installing a software in a computer]. This was a completely new sensation for us.- I see. In other words, you are saying that, via the RAM system, visual information that enters the brain becomes effectively the same as consciousness gained from [physical] experience. This reminds me that in a past interview with Ando-san, she said that by using the RAM system she is able to share images that she has in her mind with other dancers. What does that mean?

- We are told that in The Forsythe Company, when they do training for improvisation they use an image like imagining that they have a lines extending out from the ends of their two arms/hands, and that they will set the conditions for each practice session by saying, for example, “Today the lines will be two meters in length.” And, they take time in meetings to set conditions not only for the length but also details the physical qualities of the lines, such as their tension or stiffness. Then they practice repeatedly until they all get the same image, and it is only then that they enter the improvisation stage. However, by using the RAM system, the length of the lines and their physical qualities can be verified visually, so it is possible to be sure that two dancers are moving with roughly the same image in mind. That is what Ando-san means when she says she is able to share images that she has in her mind with other dancers. This is all based on the concept of improvisational dance Ando has acquired as a member of The Forsythe Company that enables individual dancers to also be a part of a group in which each dancer (“agent”) is dancing different movements but at the same time they remain in sync with the other dancers.

- Like it was in today’s workshop, the RAM system is now being used in a widening variety of events.

- One of them is workshops in which we have dancer(s) team up with a programmer and try using the RAM system In February of 2013 we did a presentation in which we presented the results of our RAM development work, and at that time we held workshops I which dancer(s) teamed with one of our programmers and spent three days creating a new “scene.” I believe the number of participants was about 35. Among the dancers and programmers were people who came from all around the country to participate. The programmers varied from students to employees from famous game development companies. Because the interests of the participants regarding the RAM system and physical movement varied considerably, the scenes that they produced also varied interestingly. Even for dancers who have interest in using computers seldom have opportunities to work with programmers, and as a result there was a lot of appreciation for that aspect of the program.

- So, introducing artists to media technology is also part of your mission at YCAM, isn’t it? I feel that this is a necessary role and one that you usually don’t find being done almost anywhere.

- We feel that need as well, and that is why we held an intensive 3-day course for dancers and programmers in 2014 that we called the “RAM Summer Camp.” As in 2013, it mainly consisted of having teams of dancers and programmers create things, and in parallel with that, a variety of lectures and workshops were held (*1). It was a packed schedule for the three days, but we believe that by giving the participants an understanding of the history of what has been done until now, what the actual work being done by both sides consist of and what the possibilities are for the future, they all came away from the camp with a rich experience of the possibilities of collaborative work.

- Have you ever created a dance piece using the RAM system?

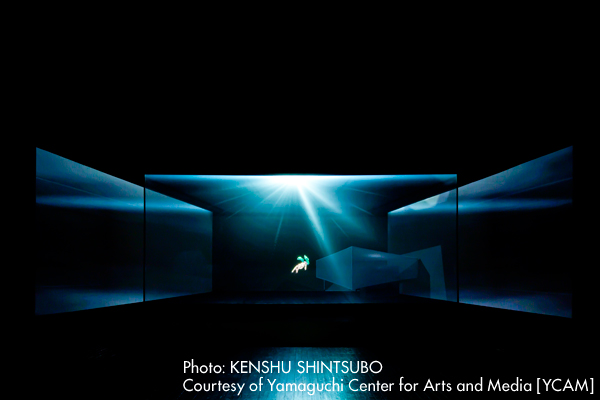

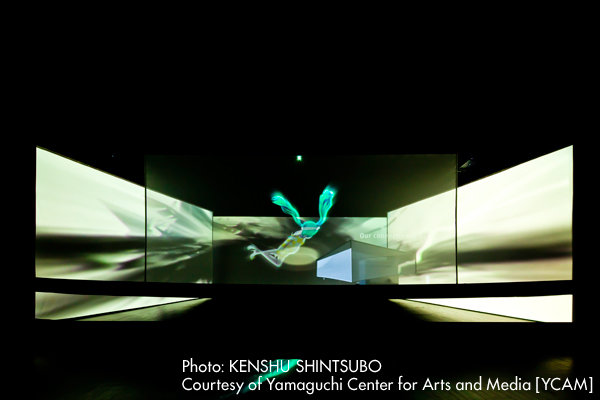

- Yes. Since I felt that the issues involved in the RAM system would not become really clear unless I experienced creating a dance piece once, we created a performance piece titled “Dividual Plays – Dialogue between physical unconsciousness and the system” in January 2015. We had Yoko Ando, former Netherland Dance Theater member Kenta Kojiri, Berlin-based Yui Kawaguchi and Ryoji Sasamoto, who returned to Yamaguchi after a career in New York, participate in the performance piece. And, we had architect Tsuyoshi Tane participate in the space design.

Until this project, we had mainly shown the “scenes” we had created on the RAM system to the dancers by displaying them on a screen. This time, however, we tried a new concept in which we made a bunch of small devices with mechanisms that made them actually move and composed a scene with them. We called this our “box garden” and in it we had the dancers move around in this virtual space and as they did, the motors in the devices would turn and cause actions such as a fan blowing up a spout of mist. For the performance, it was set up so that the dancers could see the scene and the devices on screens set on the four sides of the stage. From the audience seating, the audience could see the dancers and the movement of the dancers and the devices and the video of the scene as displayed on a screen.- If you don’t have an awareness of the virtual space, it could appear to the audience to be no more than a stage with the movement of the dancers and the devices, couldn’t it? However, if you explain what is happening beforehand, the element of discovery will be lost for the audience.

- Yes, that was exactly the issue. In fact, it would be great if we could have everyone in the audience experience using the RAM system and the performance devices before seeing the performance, but of course that isn’t possible. In the post-performance talk we gave an explanation, but it was difficult to communicate the substance of it. There was also the possibility of using the system only in the creative process where we are trying to work out the dance elements for the piece and then do the performance without the sensors attached to the dancers, but that would eliminate the very element that we wanted to try out most in this project. In short, because we were trying to take on the challenge with no compromise, straight on, it was very difficult.

- You had set the hurdle very high for yourselves, hadn’t you? (Laughs) But, I think this gave you a finger hold on a great number of new possibilities.

- That’s true. We also had the Japanese record holder for the 400 meter hurdles, Dai Tamesue, come to give us advice about how the RAM system could be used to advantage by athletes. And, although it is still something in the future, we have also had proposals for its application in projects for the benefit of the physically handicapped. I think the possibilities for expanded use of the system are great.

Said in simple terms, the reason that there is this much attention focusing on the RAM system is the fact that, in the process of feedback between data and the body, this system can create images of the shape and movement of the body. We believe that RAM is a system that can be used to research and find applications for that imaging.- The RAM software is in open-source format and posted on the Web so it can be accessed freely. Aren’t you interested in protecting any intellectual property rights?

- Since we are allowing open access to all the scenes we have created, the way the motion-capture system is constructed and the applications we have created, anyone can download them and use them. Even without any special [computerized] environment, people can rewrite the code as they please with essentially free software. Since our system isn’t a finished product, we want to have as many people as possible use it and then get that feedback. Rather than keeping it in closed source, we have decided that there are more benefits for us in keeping it open under an appropriate licensing. To begin with, this system is something that we have constructed by using the products of numerous open-source projects.

- Would you tell us about the RAM development project and the team working on it?

- With YCAM InterLab, I basically do the development for the software, etc., while the video engineer and dancer Richi Owaki does the design work, etc., for the product parts, and we are all working with a large number of other team members like the producer Akiko Takeshita on this ongoing project. We have also worked together with a number of outside specialists from the beginning of the development project that have contributed important ideas, such as the sensor specialist Yoshito Onishi and the programmer and artists Satoru Higa.

About YCAM and InterLab

- YCAM is a facility that was established with the ideal of being a public facility that could serve base for media art at the nascent period of Japanese media art.

- It all began when Yamaguchi City had adopted a basic “Information Culture Capital” plan that involved attracting IT industry companies to the area around the present YCAM facility and then building a facility that could be shared for the joint convenience of the industry employees. From there, the idea emerged to make it a culture facility, and it appears that the idea then developed in the direction of creating a media art facility. Around the time of the facility’s opening there were a number of problems such as some strong opposition to the plan, but thanks to the efforts of a lot of people, it eventually emerged successfully in its present form.

- Would you tell us about the makeup of the YCAM InterLab members?

- Until last year, we had nine members, including myself and Owaki, and Takuro Iwata, who is in charge of a number of areas, from digital fabrication to stage performances and exhibitions, the production manager Clarence Ng Kian, who is responsible for scheduling and budgeting, Fumie Takahara, who is a lighting engineer and skilled in regional research, the acoustics engineer and programmer Junji Nakaue, the server and network engineer and programmer Yohei Miura, the graphic designer Naoki Ise and the video and electronic handicraft specialist Keina Konno, all of whom can be said to constitute the YCAM technical staff. However, from April of 201, all of the staff, with the exception of those involved in administrative roles, are now referred to by the name InterLab. From the beginning, there was nothing that was done purely by our technical staff but rather YCAM people with all types of specialties had come together each time to realize project ideas, so I believe this has been a natural progression.

- Was there a concept from the beginning of forming a specialized technical group as InterLab?

- At the beginning, I believe that the only one on our staff who could be considered a professional engineer who was knowledgeable in media art was Shiro Yamamoto (currently freelance). After that, you can say that we gradually gathered the kind of technical staff needed for theater operation, including lighting, sound technicians and stage art specialists, and I myself joined the staff as a theater sound chief. At the time, I had just graduated from the Gifu Prefectural International Academy of Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS) and I had no experience with theater whatsoever, so I went for a three-week internship at a theater in Tokyo and studied hard to learn as much as I could.

- The opening performance of YCAM was Iris by Philippe Decouflé. I went to see it and was surprised to learn that such a quality performance had been supported by such a young staff (laughs). IAMAS is known for the many media artists it has produced, and I hear that many of the staff of YCAM were at IAMAS originally.

- Yamamoto was also an assistant at IAMAS, and Nakaue was also from IAMAS. At YCAM as a whole, there are now four people from IAMAS. IAMAS has a high teacher-to-student ratio and it is a school that actively makes use of artists in residence, so foreign artists were always in residence and doing projects with the students. It is a school where the buildings are open 24-hours a day and it is in an area were there is almost no local entertainment facilities and the like where the students can hang out, so the students are always in the school, so it had the feeling of one big academic family. I studied there as a member of the sixth class after the academy opened and I majored in sound and programming, and it was a place where the students came from all types of different backgrounds and ranged in age from 18-year-olds to people in their 60s, so it was a very stimulating environment for me. Among the graduates are Rhizomatiks’ Daito Manabe and Motoi Ishibashi, the artists Tadasu Takamine, Ryota Kuwakubo, Daisuke Yamashiiro, Soichiro Mihara and others.

- In addition to the RAM project, YCAM has applied its media technology in a variety of other experimental works. Looking at the domestic Japanese artists that have created works in residences there just since 2010, it is indeed an impressive list, including contemporary dance artists Hiroaki Umeda , Tsuyoshi Shirai and contact gonzo , musicians Ryoji Ikeda, Ryuichi Sakamoto and Shuta Hasunuma, artists Shiro Takatani, Tadasu Takamine , Tetsuya Umeda and Rhizomatiks, and in theater, Toshiki Okada . Was that YCAM’s policy from the beginning?

- From the beginning, the artist in residence program was one of the pillars of YCAM’s activities, and for the creation of Philippe Decouflé’s dance piece Iris , his team stayed here in residence for quite some time. But it wasn’t until PATH in 2004 that the InterLab staff began to work in collaboration with artists to a larger degree. For that project, we had the lighting artist for dumb type, Takayuki Fujimoto , who had helped out on projects from the very beginning at YCAM, and Manabe-san and Masahiko Furukata-san, the musician Kazuhisa Uchihashi-san, the singer UA-san, and then we joined in and developed a new performance tool for sound control and a lighting system to connect to it, etc. The tool functioned so that Uchihashi-san could draw a line on a screen and the singer’s (UA’s) voice would move around the performance space in accordance with that line. That time we had 23 speakers positioned around the ceiling of the performance space and a large screen was hung and a large number of LED lights were used. Our sound device was created on a pen tablet and it was designed to perform a variety of functions, such as the ability to control the sound by the strength of the pen input and the capacity to be used like an instrument for improvisation of the sound mixing. There were six input/output channels that made it possible to manipulate six sound tracks on one screen, and it was programmed so that the [changes in the] sound caused changes in the lighting and video projection. Uchihashi-san is still using that sound software on his concert tours.

- In 2007, you presented the work LIFE that linked video to the movement of mist.

- The work LIFE – fluid, invisible, inaudible… was an installation work created in collaboration by the musician Ryuichi Sakamoto and Shiro Takatani of dumb type, and it involved projecting video images on mist in an aquarium tank. When the mist disappeared the video images would disperse with it, and when new mist filled the tank the images would slowly appear. The system, in which the sound was also linked to the mist and the video, was created by InterLab, with the artist and programmer Ken Furudate and Manabe-san in charge. We also participated, in part, on the creation of the piece True – Honto no koto (2009) in which Fujimoto-san used a system the connected LED lighting with myogenic potential sensors in collaboration with dancer Tsuyoshi Shirai. Hiroaki Umeda-san’s piece Holistic Strata (2011) is one in which we participate full-scale in the production of. Also, as a project celebrating YCAM’s 10th anniversary, we worked with Ryuichi Sakamoto on the installation FOREST SYMPHONY . In this work, data gathered on the slight bioelectric potential that flows from trees in eight locations around the world were sent to on a daily basis and then used to create a “symphony” at YCAM.

- How is it decided what artists YCAM will work on collaborations with?

- We work on many collaborative projects with artists as well as technologists and researchers. Now we are working with the South Korean artist Moon Kyungwon on the production of an exhibition that will be the culmination of a 3-year research and development project titled the “Promise Park Project” (*2). This time, in addition to Moon-san a lot of collaborators are participating. As, for how we decide on the artists we work with, there are cases where the InterLab members do research and propose people they find and there are also cases where artists come to us with project proposals. With the larger projects, preparations have usually begun a year to a year and a half prior to the start of the actual projects, during which time we have a series of brainstorming session with the people who will be the main members of the project to think about the possibilities of what can be done and begin development of [software] to be used. The residence periods vary by project, but usually there will be a number of initial visits of 1 to 3 days each. During these, things are tried and the basic framework is created, and in the end a period of anywhere from one week to a month is spent in the creating the work in the actual exhibition/performance space.

- Would you tell us about what you see in the future for YCAM?

-

I think the 10th anniversary of the opening of YCAM has brought us a good opportunity to think about directions for the future. We have decided that, while continuing efforts in our fundamental areas of artistic expression and education, we want to try expanding our programs to some degree into a wider range of activities that include community projects and projects with researchers in a variety of fields that result in new input and output. Some examples are the

Think Things – ‘Mono’

(Think Things – “Things”) project and the

‘Asobi’ no Seitaikei

(The Ecosystem of “Play”) project that we initiated this year, which are audience participation type projects based on our fundamental creative approach and provide events where children have the chance to use the software platforms we have developed at YCAM to participate in creating things. We don’t think of “technology” as something exceptional in itself, but rather as something that can function like any other ideas to expand the choices and possibilities available to people. YCAM’s strength is the way we use technology and new approaches to expand possibilities in the arts and education. Although we often gain inspiration from technology, it is not our purpose to use technology itself. Most of what we do think of ideas that enable us to say, “If you are going to do something like that, adding this [technology] might make it even more interesting.” Our job is to take the results of a variety of research projects and try applying it in the arts and other areas, and if we can’t do it with our efforts alone we bring in outside artists and create networks with other specialists like technologists one after another so that in the end we can help create and show people things that are really good. Although at times it may look like we are in a position where we are applying [existing] applications in ways that the artists can use, I believe that YCAM is a place where we can do that naturally and productively.

- Listening to your words has made me see that YCAM’s InterLab is a group of people with the specialization and [artistic] sense to be able to understand both the [products of technical] research and the artists to an extent that you are able to make proposals to the artists for making the things they are trying to do even more interesting and creative. I want to thank you for giving us your time for this long and very informative interview.

Richi Owaki (YCAM Video Engineer/ Media-turge)

- I would like to begin by asking you how you define your specialty.

- My specialization is as a video (imaging) engineer, but I also dance and in that sense I’m a person involved in artistic expression, and because of that I can serve as a medium for the artists capable of explaining things to the technicians, and in that sense I call myself a “media-turge.” In its early stages, the role of InterLab was to connect artists to [media] technology. In terms of the RAM project, we served as the connection between the dancers and the programmers. Also, in very specific terms we proposed ways that the artists could use projectors to effectively project the images they wanted to use in their artistic expression. Since we understand both sides, we mostly served as that kind of plug to connect the artists to the technology. From there, we gradually became involved with the creative process in the idea stage when it was still taking shape in the artist’s mind.

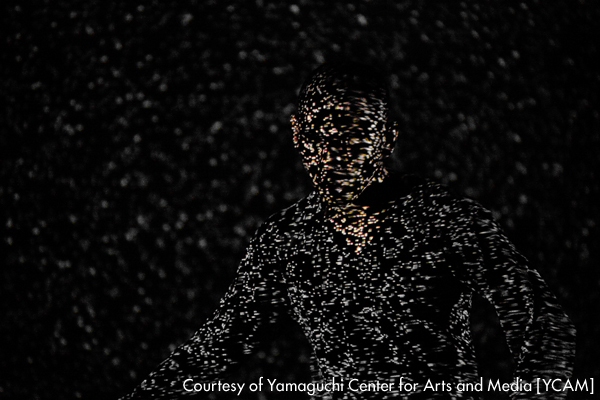

- Among the dance works that YCAM has played a major role in the creative process is Umeda-san ’s representative piece Holistic Strata . Now Umeda-san is one of the Japanese dancers receiving the most invitations to perform overseas. Holistic Strata is a very beautiful piece in which the motion of the sensors attached to his body are linked the pixels in the video images being created in real-time, so that the pixels become a particle swarm that moves around like falling rain or a whirlwind.

- For the first week we went directly into the sound and lighting tests with no prior preparations of preconceptions. Since Umeda-san is knowledgeable about the technology and can operate the equipment, we gathered a group of programmers and had them participate in the discussions from the early stage of the conceptualization for the work. At first, the working theme was “optical illusion,” so the questions were, “what is illusionary light?” and, “what is illusionary sound?” and we began searching for answers through trial and error. And we also did interviews of people who are authorities on optical illusions. Umeda-san is one who does the operation of the equipment by himself. Since his performance style is to press the buttons to start the sound and video and then go out on the floor to begin his movement, it was necessary for him to have discussions directly with the programmers from the development stage.

- This is also true with the RAM projects, but it seems that many of the works InterLab helps create involve real-time feedback of a variety of information of things happening on the stage.

- It was just about ten years ago that the performance of computers started improving to the point where we could finally use them in that way. In the past, what was called video art was mainly simply playing pre-recorded sound and images. For example, if we had tried to do a work like FOREST SYMPHONY ten years ago, it would probably have involved getting the recorded data first and then taking it to the studio and converting to sound and then playing that from the speakers of a player.

- There are a number of interactive dance works such as Angelin Perljocaj’s Helicopter and Chunky Move’s glow that are of the same type as the ones you have created in the RAM projects. However, there is always the danger that these types of works will become merely advertisements for the technology, isn’t there?

-

Of course, we are involved in these projects because we want to help the artists create interesting works, but to tell the truth, we never know if the results will be works with a good balance [between the artistic expression and the technology] until we actually give it a try. If there are generally people who design [physical/tangible] things and other people who design [intangible] things like performances and events, and if you create the physical thing first, the only thing you can do is to think of a way to use it in a performance. But, if you create the intangible thing first [like a performance or event] it will become a process of preparing the physical things afterward. In the past, it was necessary to decide which one you were going to start with as your working base, the intangible thing or the tangible thing. But, not now. Today, the RAM approach is based on the possibility that the two can always be interchanged or modified if you try. This approach isn’t limited to the RAM system. For example, what we tried in our “Think Things” participation type exhibitions was to bring a new aspect to playing that, unlike playing a video game where the winner or loser is decided according to a fixed set of rules, enables a new, more organic and flexible type of relationship between the tangible “things” and the intangible “things” that allows you to change the rules as you play. I think of what I am doing at YCAM as a form of “critique of technology.” For example, if the video used in media art is shown in the display as a finished work, it is no different from a movie. I believe that the basic stance of media art should be something that always includes the element of questioning and the critical approach that naturally involves such questions as, ‘what is the essence of recording images with a camera” and, ‘what is the essence of the display environment’. As a base for media art, YCAM should take a critical approach to technology, including sound and lighting, and furthermore, I believe that it should also take a critical approach to art works and things like the communities we are involved with. To do that, we need to engage in broad-based discussions and debate and I believe that we should take a stance of openness and transparency in creation as a prerequisite for everything we do.

Yamaguchi Center for the Arts and Media [YCAM]

Opened in 2003, YCAM is a comprehensive cultural facility sharing the same complex with the Yamaguchi City Central Library. The YCAM facilities include Studio A, a space suitable for theater and dance performances (seating capacity 450); Studio B, a free space suitable also for exhibitions; Studio C, a space suitable for film showings with a screen and seating capacity for 100; and rooms for production work and education. Through its Research & Development Project the center conducts a variety of programs, including the creation of original art works through the use of media technology and development and offering of programs connecting citizens through media technology as a way to contribute to communities. A unique aspect of the center is its development team known as “YCAM InterLab” with its staff of engineers skilled in media technology who work with outside artists and others on a wide range of projects.

https://www.ycam.jp(*1)

A lecture by Chris Sutter (artist, specialist in technology and performance) about the practical history behind the RAM system; a dance workshop for programmers by Yoko Ando; a programming workshop for dancers given by the RAM development staff; a lecture concerning technology for expanding human functional capabilities by Tokyo University professor Masahiko Inami and Keio University professor Yasuaki Kakehi, etc.(*2) Promise Park Project

This is a collaboration between YCAM and Moon Kyungwon, who served as the representative artist of the South Korean pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The project resulted from an installation created by Kyungwon based on the concept of “a park of the future” in the group exhibition “art and collective intelligence” in 2013. Positioning parks as public spaces in the society, fieldwork was conducted concerning the role of parks from historical and comparative culture perspective with a scope expanded to include the networks of today’s IT-oriented society. The result of the research and a large-scale video installation were presented.

Dividual Plays – Dialogue between physical unconsciousness and the system

(Jan. 2015)

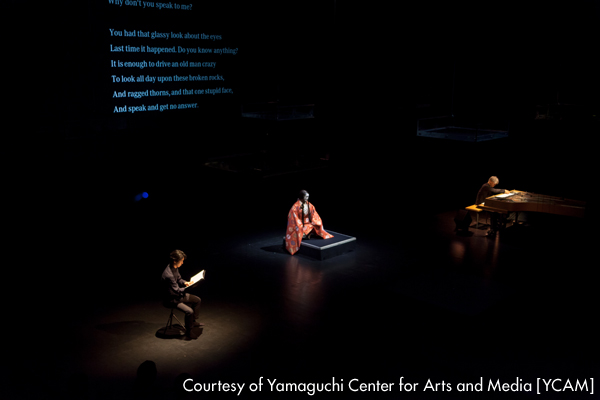

Keiichiro Shibuya + Toshiki Okada Vocaloid Opera

THE END

(Dec. 2012)

Photo: KENSHU SHINTSUBO

Hiroaki Umeda

Holistic Strata

(Feb. 2011)

Mansai Nomura + Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani

LIFE – WELL

(Oct. 2013)

- Listening to your words has made me see that YCAM’s InterLab is a group of people with the specialization and [artistic] sense to be able to understand both the [products of technical] research and the artists to an extent that you are able to make proposals to the artists for making the things they are trying to do even more interesting and creative. I want to thank you for giving us your time for this long and very informative interview.

Related Tags