Lighting as multimedia performance, in the creative style developed at Dumb Type

- Kawaguchi: Fujimoto-san and I are both members of Dumb Type. I joined the company in 1999 and you were a participating member from the company’s earliest days. From what I hear you were not in charge of lighting at first. Can you begin by telling us how that came about?

-

I was a high schoolmate of the late Teiji Furuhashi, who was a central figure for me and for Dumb Type. We both went on to study at Kyoto City University of Arts.

Once there, I chose to join the volleyball club, and so did quite a list of people who would later make a name for themselves in the art world. To name a few there the artist Noboru Tsubaki a few years before me, and the artist Hiroshi Fuji, one year my senior, and then me. After that, Toru Koyamada who would later become a Dumb Type member and Koichi Emura of Kyupi Kyupi joined. A year younger than them Hiromasa Tomari who would also later become Dumb Type member. After him came Kenji Yanobe and Tadasu Takamine, as well as the contemporary artist Nobuaki Date who makes ukuleles, and a little after them came Yoshimasa Ishibashi of Kyupi Kyupi. It is sort of a legend that all of these artists started out from the same volleyball club sweating and doing the same hard training together. What’s more, Fuji, Koyamada, Tomari and Takamine are all from Kagoshima Prefecture and were a close-knit group as a result.

After Fuji joined the University’s theater company “Gekidan za-Karma” that would eventually become the forerunner of the company, other artists who would later become core members of Dumb Type, including Furuhashi and Koyamada, also joined the “Karma” and that is how Dumb Type came to be formed later on.

I myself didn’t join the Karma but continued to study oil painting while also making stage sets as a part-time job that I had begun in my freshman year at the university. Making stage sets was a common part-time job for art students and we made sets at theaters like the public halls and Kaburenjo (theater for geisha ) in Kyoto. In the process I became familiar with the language of the theater and how things happen on stage, as well as the stage hierarchy; who the director is and who you should take orders from for each job. This work became very interesting to me and by my senior year in university I was basically working as a freelance set builder.

When I graduated (in 1984), I rented a large studio space with about 50 sq. m. in the Sagano district of Kyoto. And since the floor above it was vacant, the Dumb Type members who were graduating around that time decided to rent it as their office. Then I became involved for the first time with one of their productions because I knew a good deal about theater. That was Suimin no Keikaku (Plan for Sleep), their first production outside the university, and my role was as the set builder.

For the production 036-PLEASURE LIFE (premiered 1987), Dumb Type used multimedia for the first time.I had a friend who was involved in electronic circuitry and I got to join him to make a video switcher, a lighting control device and motor controllers for us. At that time I was working on the set and props with Koyamada. - K: I saw PLEASURE LIFE in a promotional video and the use of many round florescent lights impressed me and I was surprised that such lighting was possible. Was that a design by Shiro Takatani?

-

Takatani did the designs for

036-PLEASURE LIFE

,

PLEASURE LIFE

,

pH

and

S/N

. Takatani’s lighting is cool, but he doesn’t use stage lighting. He is an architect and was working at architectural offices, so he chose his lighting [fixtures] from architectural-use catalogs, and what he couldn’t get that way we made by ourselves.

Around the time of 036-PLEASURE LIFE , Sony released a monitor that could take video input (SONY PROFEEL) and production-model VHS cameras could also be purchased about the same time. That made it possible to display images in real time on a monitor as you were filming them live with a VHS camera. But, it wasn’t possible to create our own computer graphics at that time, or at least nothing better than something with the appearance of an electrocardiogram image. Even so, Dumb Type kept pace closely with the technological advances of the times in creating new modes of expression.

By the time of S/N (premiered 1992) the performance of the Mac computers had reached the point where we could create our own computer graphics. Video projectors were expensive but Dumb Type also managed to buy about four of them and Takatani was put in charge of [video] visuals with Furuhashi. Then it was decided that someone should be in charge of lighting, and since I had some knowledge of the workings of theaters, I volunteered. The first production I did the lighting plan for was OR (premiered 1997). - K: So you started as a set builder and moved up to lighting artist.

- Since I had never been formally trained in lighting technology, I called myself a “special lighting technician.” (Laughs)

- K: What was it like working on S/N ?

-

S/N

was at first (#1) an installation work, but while we were in the midst of talks with Denmark’s Hotel Pro Forma about doing a collaboration, Furuhashi collapsed. So we had to leave him behind and go to Denmark without him. But then we got a letter from him saying that he was HIV positive and the disease had developed into a full-fledged case of AIDS. That brought a clear vision of a theme for

S/N

as a performance work. We were already scheduled to go to Adelaide (Australia), so we worked hard to get the work ready. Takatani did the lighting plan and I worked with the local Australian staff—asking them things like what a “patch” was—to put together the program and then work desperately to operate it. That was my first experience in lighting.

Eventually, each of the Dumb Type members became busy with their respective jobs and I became the technical manager responsible for using a CAD program to do of all the blueprints for a production including stage sets, audio, visual and lighting. A Dumb Type project can’t come together unless there is a centralized system, and since I was familiar with sets too, it became my job to do all the set and lighting blueprints and deal with the outside technicians, etc. - K: The first work that you did the lighting plan for, OR was also the first Dumb Type work that I participated in as a performer. The symbolic use of pure white strobe light against a pure white wall was so blinding that I experienced complete “white-out.” I was supposed to run at full speed across the stage when the light was white and the instant I stopped there was complete blackout. And when the strobe started I was supposed to run again. The effect of that lighting caused me to completely lose my sense of direction and distance, and I ended up bumping into the walls again and again. It was really a frightening experience.

-

When I was working on

S/N

I found a strobe that operated with DMX 512 (a protocol for stage lighting fixture control) controller called Dataflash, which enabled you to control both the brightness and speed. It looked interesting and I got the idea that I’d like to try working with it. In

OR

I used that strobe, HMI and HID lamps and did the work with the whiteout phenomenon (the phenomenon in which the entire field of vision becomes white, thus causing the loss of any sense of direction) as a theme.

Furuhashi had died and we in Dumb Type were trying to deal with that reality, so it was a time when I was thinking a lot about the border between life and death and this work came out of discussions we were having within the group about this subject. As we were working on this piece we were talking about things like the point at which everything becomes white and you can’t see anything, or the border of existence where you don’t know whether you are alive or dead.

After working on OR in a process that was mainly trial and error, I found motivation to work seriously in lighting. The stage lighting scene in Japan was, in a way, behind the times back then. Because the theaters were fully equipped for lighting, that seemed to have the reverse effect of keeping new things from coming in. In visuals and video the technology was rapidly progressing and at the time we were doing OR it was already commonplace to be using SMPTE to synchronize visuals and music with simultaneous signals. But for a long time that wasn’t happening in lighting, so everything had to be operated and adjusted by hand.

With OR , however, Ryoji Ikeda joined as a musician and I was able to insert “doom” sounds in the soundtrack as trigger sounds and use a device to have the lighting operated from those triggers and integrate it with sound and Dataflash. The number of patterns were limited, and the lights other than the strobes had to be operated manually, but I was finally able to get the lighting to operate automatically in synch with the sound in that way, which was rewarding for me. - K: In OR there are many scenes where the lights are flashing on and off so fast that it is at the boundary of what the eye can detect. I felt that I was seeing that limit of the eye to discern flashes.

-

In fact a florescent light flashes but it is just too fast for the human eye to detect. ON and OFF—every moment things are beginning and ending, things are born and end—despite this constant repetition, in our minds we perceive it as a continuous flow of time. Something like the ON/OFF of lighting can connect to themes like the gray zone between life and death or to what degree the things that you think are you are really you.

So, whether light is flashing rapidly or whether it crosses the boundary of perceptibility and becomes pure white, and in Ikeda’s case it can be a case of looking for the boundary between sound that is heard with the ears and sound that is felt with the body. The search for such boundaries became a sub-theme running through OR . - Tsuboike: What kinds of collaborative work went on in OR ? When Furuhashi-san was alive he did the overall directing, so it must difficult after he died.

- Takatani assumed a central role, and since there was already sort of a heritage in terms of how works were created, everyone would gather in the office as we had always done and talked things out freely. In that way we got a shared sense of the thematic substance and then moved forward with an attitude of bring every idea that came out of the discussions to the stage. The result of that process was about a two-hour work, which was too long. So, we talked again that night and by the next day we had it down to about 40 minutes (laughs). If you think about it that way, it probably sounds like a pretty unstable creative process.

- K: And the ideas and images for the work came not only from the technical team but also in good numbers from the performers as well. That was something I experienced for the first time with OR ; that feeling was that nothing ever got decided, but that was also a very interesting process.

-

When I first began working on the lighting for

OR

computers were becoming more user-friendly and we had access to world-class DMX consoles as control standard. And in that sense it was a great time to start out in the profession. Until then the patching method and controller format and standard differed by maker, which meant that everything had to be dealt with different controllers each time. But with the new systems, as long as you had a DMX console anything could be controlled, no matter what dimmer you connected it to.

Prior to that, it was a matter of how much you knew about the programming methods for the different types of consoles or how skilled you were at raising a fader, but with the new digitalized technology the level of a technician’s experience mattered little and the playing field was suddenly leveled for everyone. In that sense I considered myself to be luck entering the profession at the time I did.

New projects using LED lighting

- T: So, it was the beginning of the new era of computerized lighting control.

- The basic technology I use today originated in the early ’90s, which is the same period when Dumb Type and I were starting out. In the mid-80s multimedia artist like Laurie Anderson came to Japan one after another, and in that sense as well, I believe we were very fortunate to be starting out a time when we could see such works. It was a time when we asked “What shall we do next?” or “Wouldn’t it be great if we could do something like that?” and the technology was there to make it possible.

- T: During that period of technological advancement, you also began making effective use of LED lighting in projects other than those of Dumb Type.

-

The first time I used LED lighting was for Kawaguchi-san’s solo performance work Night Colour in 2003. As I said earlier, it had become possible to synchronize and control sound and video tracks, but it was not easy to set up or change lighting with that kind of freedom. What’s more, even if you wanted to change lighting in synch with video frames, which are projected at a rate of 30 frames per sec., the rate at which lighting fixtures using filaments can be turned on and off is not fast enough to match the speed of video frames (one frame every 0.03 sec.).

It was when I was thinking about a solution that I found LED lighting equipment. With LED there would be the advantage that the colors could be changed at will, so at the time of Night Colour performance, I visited the offices of Color Kinetics Japan, the company that handled products, and got them to lend us LED lighting equipment for the first time. I quickly found that their operating speed was very fast and they required less voltage than conventional lighting. And since LED is digital lighting equipment, all of the operations could be controlled by computer. I knew I had found something great.

With Night Colour I had found out what digital LED lighting equipment could do and realized that it would make it possible to create works that could be staged virtually anywhere, including places where it had not been possible for Dumb Type before due to the lighting facilities. That is what led me to write a plan for the work Refined Colors. Refined Colors (2004) is a work performed by three dancers with a technical staff of two and 28 LED light fixtures and two laptop computers. Other than that, all that is needed to stage it virtually anywhere is a stage space with white floor and walls put up at the back. All the equipment fits in about five travel suitcases. And we traveled like that to do performances of Refined Colors in several cities in Japan and Europe, three East European countries and Southeast Asia.

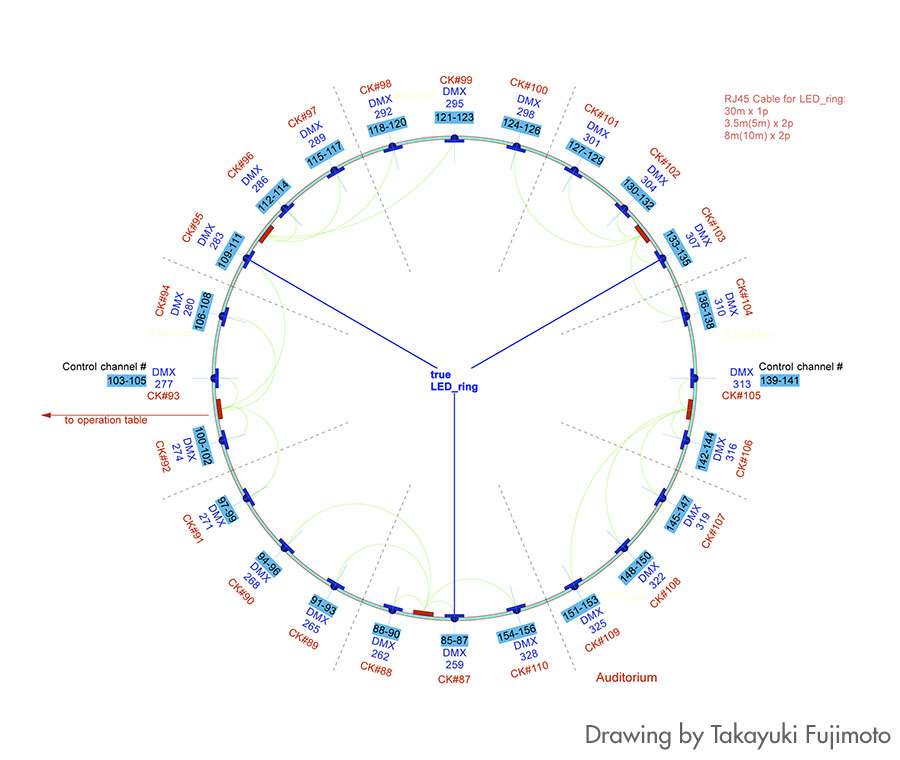

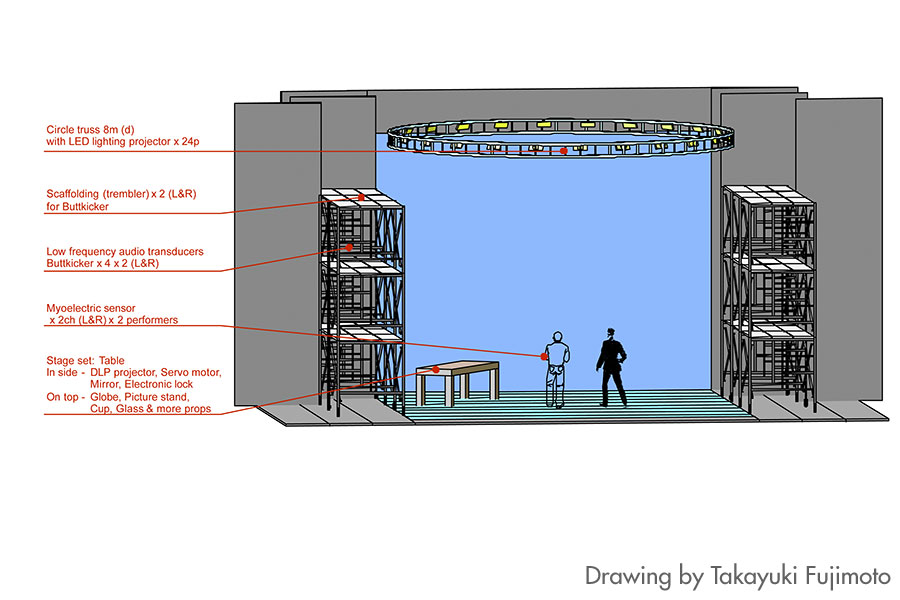

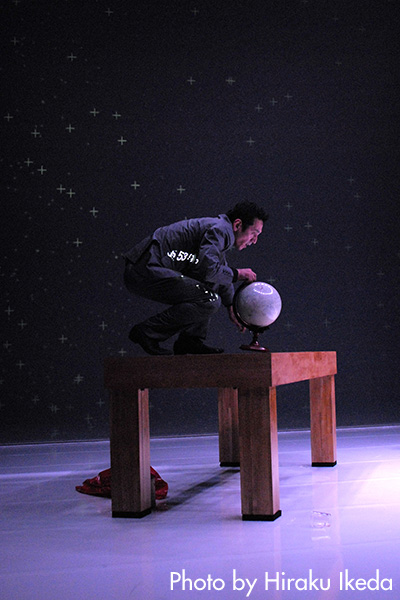

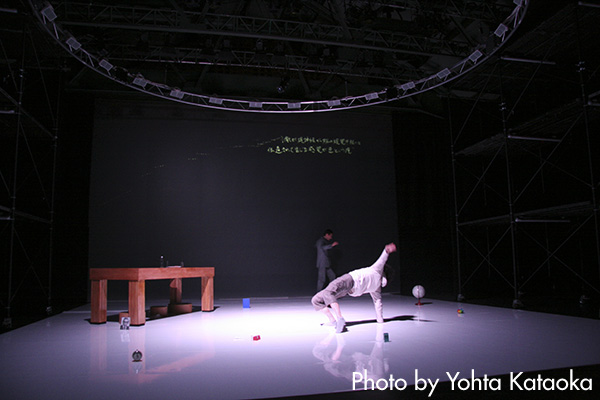

In 2005 we created the work path ( https://path. ) with the singer UA and the guitarist Kazuhisa Uchihashi, who does the music of the theater company Ishinha. With Refined Colors the sound and lighting where synchronized at certain designated points, but path is a completely improvisational work, so we designed it in a way that the lighting and visuals are controlled by a computer program that analyzes the guitar sounds and vocals coming from the performers’ improvisation in real time. Depending on the incoming sounds picked up by the computer the visuals and lighting will differ each time, which means that the concert will be different at each performance. Then, the next work we planned after that was true .ycam.jp/ - T: In true the performers were Kawaguchi-san and Tsuyoshi Shirai. It was a work in which the sound, visuals, the lighting and the performers movements were all synchronized in such an organic way that it created a mysterious environment for the audience.

- With Refined Colors we created a contemporary dance work and with path we created a music work, next we wanted to do a performance-centric work building on the technical expertise and know-how acquired over the years with Dumb Type works.

- T: What did that technical know-how include specifically?

-

When we wanted to add more aural and tactile aspects to the visual effects we had achieved using LED lighting, we were able to find lots of things around us that could be used.

First of all, I asked the programmer/artist Daito Manabe, who had been working with me on program designs since Refined Colors , to help us by bringing in the myoelectric sensor he had developed and a commercially sold oscillator called an BUTTKICKER (for making things like chairs vibrate) used in experiential type games, etc. Manabe-san had already used his myoelectric sensor in creating Kawaguchi-san’s performance work TABLE MIND , so we knew it could be used. We also got some of his friends from the technical field (Seiichi Saito and Satoshi Horii of Rhisomatiks, and Motoi Ishibashi and Masaki Teruoka) join us to make technical devices.

In true we had Kawaguchi-san and Shirai-san wear myoelectric sensors so that we could use their muscle movements as triggers for operating the lighting, sound and visuals. Also, the system was set up so that my control of the lighting could link to sound control and sound triggers could operate the lighting. In this complex interaction all types of things became control cues.

Of these, it was the myoelectric sensors that I wanted to use most. These sensors detect the small electric currents generated when muscles are moved. I though these signals could be computer processed to create a variety of media effects in real-time for artistic expression. In its ultimate application, this could mean using the signals (for muscular movement) from the brain could be used to operate media functions on the stage.

For example, when making a scene where the sound and lighting changes in time with rapid movements of the performer’s body, you would normally begin by creating the sound and light program and then show it to the performers so they can move in time with it. But that will produce a scene that is the result of the performers training to make their movements fit a given set of prescribed conditions. But in the case of true it is a work where everything begins from the movements of the performers and the surrounding conditions change in response to those movements.

And with the oscillator, we rigged a system using oscillators built into the structure supporting the stage and made the structure shake with a subsonic sound of 20 hertz that can’t be heard by human ears. The audible range for human ears is between about 20,000 and 20 hertz. Any sound below that range that you feed into a speaker can’t be heard because the frequency is too low. I got the idea that this lower range sound could be experienced by means of oscillators. In true we created a scene where sound actually climbs from a very low range to a very high range. At first the frequency is so low that it can’t be heard as sound but the under-structure of the stage shakes. Then, as the frequency rises it gradually becomes audible as low sound and continues to climb until it is too high to be heard. - T: How is that kind of technical form of expression related to the theme of true ?

-

It is related to the meaning or the work’s title,

true

. Is it true that we really exist as we think we do? That is the theme. We think of sound as the things we can hear, but since sound is vibration there are sounds we can’t hear. So what is sound actually?

The performances may be said they are live art, but aren’t they actually just performing previously choreographed movements in time with the sound? So what does “live” really mean?

It is the same with color. We can ask things like, “Why do we see so many different color from combinations of RGB (red, green, blue)?” We think that the world we see in front of our eyes is the real world made up of absolute and unchanging things, but is it “true” that things exist that way. So we decided we would give that some thought. It is like a Zen riddle (laughs). - T: In true you collaborated with many creators like Manabe-san. How do you proceed with such multimedia collaborations?

-

The question of how to best share information and create a work together is something we are always dealing with. I have tried a number of methods, such as creating something like a school bulletin board on the Net where people can leave messages to each other, but I actually am still in the trial-and-error stage. Within Dumb Type we basically know what each other are thinking and we have a language and terminology of our own, so there is more room for ambiguity, but when we are working on a new piece with new people, that isn’t a viable way to work.

So, with true I created a sort of work matrix for each of the members of the creative team. I divided it by scenes and posted my thoughts about what I wanted to happen in each of them like a director’s notes. But, these were not things that were already decided, rather they were ideas in progress to be developed on.

I created the matrixes using Excel and at the end of each day’s work I sent out emails to everyone reporting what progress had been made in each area, and I also had everyone send back responses about what needed to be done next. As the updates continued to be added it eventually became something equivalent to a director’s script. Members whose contributions couldn’t be explained in text would send in sound or video clips as samples. I would then check them and send back email responses. That kind of exchange was made every two or three days and I made it so that everyone had access to this information and shared knowledge of it.

Also, in the case of multimedia works, for about the first week of rehearsals everything is still disorganized as people are putting together their programs and there is nothing much that the performers can do during that time. When we start practicing and something goes wrong, the person in charge will say, “I’m going to fix this,” and he will go off for an hour or so and fiddle with the program while the performers have to wait (laughs). When that happens too many times the performers are on the verge of tears and saying they can’t collaborate that way. Of course Kawaguchi-san is all right with that, and since Shirai-san is a person who makes video works himself, he knows what the technical people are doing and can make suggestions about the systems. If it isn’t people like that, we can’t create a work together. - T: In true , the scenes were named Japanese, Arithmetic, Science, Social Studies and Music like a school class schedule.

- That’s right. The scenes were titled with the names of school subjects like Japanese and arithmetic and at first we had everyone contribute their ideas for key words to go along with them. For example, “Music is Waves” or “Music is Mathematics.” These “Something is something” key words were also posted on the matrixes so we could build specific images from them. For better or worse, the elementary school textbook is the first picture of the work that a child encounters.

- K: I was in charge of the Japanese scene, so besides my performance I had to compose specific words as well, but they just didn’t come to me. I was really at a loss (laughs).

- I had been preparing the scene from the beginning with the intention of having Kawaguchi-san do the work part. There is a scene where words are floating in a blue light and those words were taken from the text that Kawaguchi-san wrote. When you watch the scene live it looks as if the visuals are moving in response to the words Kawaguchi-san is speaking, but in fact it is the opposite. We first had a taped version of the soundtrack played and Kawaguchi-san did his talking performance in time with that. Then we took cues from that and rigged it so that the visuals and lighting operated from those cues.

- T: The work true was created during a roughly one-month residence at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM). A facility like YCAM where artists can work on multimedia works in and artist in residence type of environment or educational facilities like the Gifu Prefectural Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences and International Academy of Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS) were unimaginable at the time Dumb Type was starting out.

- YCAM is a facility the Dumb Type and the Tokyo multimedia art base Canon Art Lab (now defunct) were involved in from the planning stage. Until then, Dumb Type had primarily done its creative work overseas and I had long wondered why there wasn’t a place in Japan where multimedia works could be created. So, I proposed to them that they make this a facility equipped for multimedia creation. There were already a number of highly skilled technical people there and part of the reason I chose to create Refined Colors , path and true there at YCAM was to work with them in the actual process of creating works using technology.

- T: Are there any other facilities besides YCAM where multimedia artists can work in an artist-in-residence type situation.

- I don’t think there are any places besides YCAM in Japan, but then again there aren’t many such places any where in the world. In Germany there is ZKM: Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, and in Rotterdam there is V2. In the case of V2 the orientation is toward installation type works rather than performance, however. So, in this sense, YCAM is a unique and important facility from a global perspective. By the way, a well-known festival that also functions in this way is the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz.

- T: In terms of nurturing media arts personnel, IAMAS has become an essential organization. Most of the creators like Manabe-san who collaborated in the creation of true were educated at IAMAS, weren’t they.

- I personally have not been especially conscious of IAMAS, but the fact that it is the only institution of its type means that of necessity most of the people in the field have been educated there at some point. When you look at the profiles of the Japanese artists who have won awards at the Arts Electronica Festival, you find that most of them are from IAMAS. However, these creators usually become active in the commercial field I believe.

- T: It has been 13 years since IAMAS was launched, but is seems unfortunate to me that the uniquely skilled people coming out of its program are not helping to bring new forms of expression to the performing arts in most cases.

-

Yes. And the reason that not enough use being made of their skills is actually a problem originating with the people in the performing arts, I believe. I would like to see the people in the performing arts become more open to media art. It puzzles me why most people in the performing arts take an attitude that media art doesn’t involve them.

I don’t mean to be critical, but I see few lighting artists, for example, who are trying new things technically, and many are reluctant to try the new technical equipment that comes out. There seem to be few people who feel that the latest advances and technological breakthroughs will change the creative process and the works created. Also, in Japan it seems to me that there is division back stage that keeps the lighting artist only a lighting artists and the set designer only a set designer. The directing type work is done only be the dancers and performers and directors. But, I believe that the path should be open for people working backstage like the lighting and set people to start their own companies, create works and become artists in their own right.

Since we don’t have that, the only way new forms of expression based on new technologies usually come into use is when a performer of director happens to see it used in someone else’s work and decides it would be interesting to try. And then it becomes no more than a simple process on the level of a dancer hearing the music of Ryoji Ikeda, deciding they’d like to dance to it and then going out and buying one of his CDs. Of course, I think that an approach like Dumb Type’s is a rare exception to the rule.

Since there are a good number of people who have been trained in the latest technologies, I think it would be good if places like YCAM or ICC (*) would take the initiative sometimes to hook up technical people who are doing interesting work and performers and have them create collaborative works. I believe that would lead to some interesting results. - T: Finally I would like to ask you what you see in the future for theater lighting. LED lighting has a lot of excellent qualities including the fact that you can change colors easily, the lights have a long life span and they use less electricity. Do you think more and more theaters will go to LED lighting?

-

At first I had the vague idea that it would be good if theaters went to LED lighting, but since Japan’s theaters already have full lighting systems, I have come to realize that it would be difficult to change those systems entirely to LED. If LED lighting is introduced, I think it will be in a limited way, such only for replacing the horizon lights.

Rather than seeing LED replace the existing theater lighting, I think it would be more interesting to see people using, say, some 10 LED lamps and a computer along with your basic sound environment to create works for different kinds of spaces of viable sizes. There are many things that LED lighting can’t do, but in the realm of expanding the possibilities for use of spaces that don’t have the stage infrastructure, I believe that using LED can be very effective. And personally, I feel that rather than viewing LED as an innovation in lighting equipment, I am more interested in working on exploring the possibilities of LED as a tool of expression in various types of projects. - T: Do you have any new projects in the making?

-

Although there are no specific plans yet, I want to do a project with the Lebanese artist Rabih Mroue. It’s quite a simple idea, but I have done projects with dance and with concerts, so next I would like to do something in theater, with Rabih (laughs).

I have been touring overseas for years now and that experience has made me strongly aware of the language barrier that you encounter in theater. That has made me wish that I could help create theater works, if only on a small scale, where you would not feel the absolute barrier of language. But I still have no idea how to go about doing that.

true tour schedule (Japan and Europe)

Tokyo

Dates: Aug. 6 – 9, 2009

Venue: Setagaya Public Theatre / Theatre Tram

https://setagaya-pt.jp/theater_info/2009/08/true.html

Netherlands

・Amsterdam

Dates: Sep. 25 and 26, 2009

Venue: Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam (SSBA)

・Eindhoven, Netherlands

Date: Sep. 29. 2009

Venue: Parktheater Eindhoven

https://www.parktheater.nl/

Dusseldorf, Germany

・ Dates: Oct. 3 and 4, 2009

Venue: Tanzhaus NRW Dusseldorf

会場:Tanzhaus NRW Dusseldorf

https://www.tanzhaus-nrw.de/de/spielplan/index.html?month=vorschau#49

・Frankfurt, Germany

Dates: Oct. 9 and 10, 2009

Venue: Mousonturm Frankfurt

https://www.mousonturm.de/

Paris, France

Dates: Oct. 15 – 17, 2009

Venue: Maison de la culture du Japon a Paris

https://www.jpf.go.jp/mcjp/