- I would like to begin by asking about your recent work Hayasasurahime . The ancient text Records of Ancient Matters ( Kojiki ) the primary source of writings about the Japanese creation myths, and it has been translated into English as well. What gave you the idea to choose the little-known god Hayasasurahime appearing in the Records of Ancient Matters and choreographing a piece based on this god character using the music of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony?

-

The name Hayasasurahime doesn’t actually appear directly in the Records of Ancient Matters, but is mentioned indirectly as one of the “

Haraedo

” deities in the passage, “Izanagi no Mikoto went to Awagihara by the river-mouth of Tachibana of Himuka in Tsukushi and performed a purification ceremony, where he produced various gods.” Hayasasurahime is one of the “various gods” (

Haraedo no Ookami

) mentioned here. The first of these gods produced in the purification ceremony is given the name Seoritsuhime, the second is Hayaakitsuhime, the third is Ibukidonushi and the fourth is Hayasasurahime. This deity is similar to Amenouzume , the deity that is generally considered the founding deity of Japanese dance. If Amenouzume is said to be the deity that dances to change darkness to light, I believe that Hayasasurahime is a primordial deity that brings both darkness and light together is a state of pre-foundational chaos.

I believe that the image is close to that of the orgiastic rites of Dionysus or Bacchus in the European mythological tradition, where everyone drinks and dances themselves into state of catharsis.- In the choreographic theme of your work Hayasasurahime this time, I certainly felt a bacchanal element. What’s more, I also felt great appeal in the intellectual bearing of the composition that suggested an apollonian aspect as well. However, despite that, the choreography didn’t appear to be something you created in a calculated way. Rather, it had the appearance of choreography that created itself freely.

Yes. It didn’t have the feeling of working hard to compose a choreographed work. We got together and worked in the studio for a period of about half a year, and the work just seemed to emerge naturally from that process into its final state.- Still, it must have been quite a challenge choreographing a work to the entire score of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, wasn’t it?

- The 9th Symphony is a famous work, so I thought it would probably be good [to use] (laughs). Anyway, the title of the 4th movement of the 9th Symphony is taken from the title of Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy,” and I think that to some degree it represents a fundamental philosophical theme in European thought. European thought creates dualisms such as light and darkness, Heaven and Earth, God and mankind, the word and the flesh, and in some sense, I feel that Schiller is a poet who fused those dualisms together. And, I believe that is reflected in his poem Ode to Joy. For that reason, I think the themes in the 9th Symphony and the Records of Ancient Matters are not as distant in nature as one might think. Although it is true that most people will be a bit surprised when they see them put together in a work (laughs).

- I’m sure anyone would be surprised (laughs). The 9th symphony is composed in a way that it develops thematically through its four movements. I had the feeling that you took that into account as you composed your work Hayasasurahime .

- Yes. The composition is the same as Beethoven’s in that sense. The first movement goes from nothingness to something-ness, the creation of Heaven and Earth as the world is created from the chaos. The second movement is a conflict of light and darkness. The third movement is a fusing or merging of the two extremes in a gentle, heavenly image. Then, in the final fourth movement, the forces of evil cause the world to collapse, but at the same time that gives the human spirit to potential to harbor joy. It is joy that survives even as the world crumbles into a tragic state of chaos. So, I believe that what we created is actually rather faithful to the images Beethoven intended to express in his 9th Symphony.

- Yours is a work with various components, like the strings, horns and percussion sections of an orchestral work. The final part brings together butoh, Eurythmy, contemporary dance into a single composition that was very powerful. But, I would like to ask your creative process when choreographing a work. Do you start by putting together a solid overall plan for the work?

- You can think of dance as falling basically into two types: dancer-centric dance and work-centric dance. In the latter, the work’s image comes first and then the dancers are chosen to fit that image. There are some artists who think work-centric like that, but I am the type who chooses the dancer first, and at the moment they are chosen the work can come together in that moment. I am unmistakably the dancer-centric type. Rather than the type that wants to use the dancers for their own purposes, I am one who knows from the first encounter with a dancer that including them in the work will result in a certain type of movement that I can foresee intuitively and clearly. In my case, at the point where the final selection of the dancers is complete, it is as if the work itself is 99% determined. Rather than being a process of creating movement, what I do can be thought of as a process of simply feeding it with doses of “the water that is choreography.” It feels more like a process of “nourishing and raising” the work than a process of composing it.

As it was with Akaji Maro , who I worked with on this work, when I encounter another dancer, it is a very exciting experience and one in which that encounter opens up new worlds previously unknown to me.- Would you tell us what your actual working process involves when you are choreographing a new work?

- First of all, I have to get a sense of the unique “smell” of each dancer. Is it a tart, acidy smell, or a “sweet” smell, etc. Every dancer has their own distinct flavor or “smell” in that way, and that is what makes it interesting. Movement that fits that unique character comes intuitively from them. Also, I am not so much a pictorially oriented person as I am musically oriented. When I hear music, movement flows out of me naturally.

I try to avoid giving the dancers images based on words. Instead, I have them work diligently on forms. The reason is that greater strength comes out from the choreography if there is no room for [verbal] images to intervene, thus reducing the chance that the dancer will get carried away by an image. I tell that clearly what I want the positions of the hands and fingers and head to be and almost have them practice the forms faithfully as prescribed. Even if it is a dancer who has been trained in Graham technique, or a full-fledged ballet dancer, during the choreographing of a piece I ignore those acquired skills in them. The reason for this is that their movement will be more interesting if it is something they have never done before.By the way, in the case of Hayasasurahime , I had my Tenshikan dancers and Dairakudakan’s dancers practicing separately from July and didn’t bring them together until August, and it wasn’t until November that the Eurythmy members joined us and we had the whole cast practicing together for the first time. The Dairakudakan dancers were working hard for us practicing movement they don’t usually do.- Although you have used the term “dancer-oriented,” I feel that your works also have something like a “will” that shows itself in the composition of the work, a certain worldview and solid sense of conscious direction that makes them also worthy of being called “work-oriented.”

- It is true that there is such an element, in that I always have a sort of framework in my mind and I am fitting the movement that emerges from the dancers into that overall image.

- Changing the subject slightly, I would say that there were very few [in Japan’s dance world] who could ever have anticipated a collaboration between you and Akaji Maro. Although you both have roots in the butoh movement that traces back to Tatsumi Hijikata, you have walked completely different paths since then and those paths have never crossed to bring you together in all these years. What made you finally decide to work together on a production?

- I first got the idea that I would like to work with Akaji Maro after seeing him perform his piece Kawa no Hotori (2002) and felt a great interest in him as a solo dance artist. In 2005, we happened to both be on the program of a butoh festival in South Korea, and when we saw each other for the first time in decades at the festival’s closing party, we said enthusiastically that we should work together on something in the near future. This year happened to be my Tenshikan company’s 50th anniversary, so I took that opportunity to approach him this time with the offer to work together.

I believe that part of the reason that Maro and I were able to work together in this way now is the 50 years that have passed since Hijikata. Because during those 50 years I’m sure we both pursued our own courses thinking, “Who would accept the work of Maro?” and “Who would accept that of Kasai?” I’m sure that we both wanted to recognize each other’s work, but [due to our professional pride as artists] we each had trouble recognizing the other’s work. Perhaps now enough ground has emerged in each other that we are willing to give recognition to.- In your personal history in butoh, I’m certain that there are influences of both of the representative butoh artists Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ono, but the distance you have maintained with these two masters has been slightly different. With Kazuo Ono the relationship seems to be one of your teacher in an all-inclusive sense. On the other hand, with regard to Hijikata it seems that you were influenced and inspired by him in a number of ways but have also kept a significant distance from him.

- In the history of butoh, I believe that Hijikata was the one who did truly the revolutionary things. He was the first to include the movement of people with disabilities in his butoh choreography and make it successful as a stage work. In doing so, he completely dispensed with any idea that movement in dance was either good or bad, or that movement should be beautiful. In other words, he returned dance to fundamental questions: if there is no such thing as good or bad movement in dance, how should people train their bodies, what movements should they practice? In that sense, I believe Tatsumi Hijikata returned dance to its fundamental roots.

However, in some aspects Hijikata and I have ways of feeling and perceiving things that are almost 180-degrees in opposed direction. I believe that Hijikata maintained a posture based thoroughly on the philosophy of materialism when creating a dance work. In short, he wasn’t the one who believed that the spirit is eternal and the material is transient, but the opposite: the material is the eternal and the spiritual will eventually fade away. However, I am unable to create dance based on the proposition that matter is the only constant in the world. In that sense, you can say that I continued to pursue a different course from Hijikata.- In other words, you were not in agreement with Hijikata’s philosophical tendency toward materialism, were you? I was very much struck by an episode you told me about in the past, that you used to begin dancing to the sound of your mother playing the organ at church. Did elements of Christianity have a significant influence on you?

- Yes. Both my mother and her father, who was a banker, were active Christians. The home where I grew up might be described as a model of the “Taisho Period Modernism” that was prevalent among a certain sector of Japanese society at the time. I grew up in Mie Prefecture but the household was of the type of education-conscious families prominent in the upper middle class of Tokyo in that day. One example was that when foreign musicians came to Japan they often stayed at our home. My grandfather was good at English and frequently served as an interpreter for foreign cultural figures or visitors. So, I was definitely influenced by an upbringing where that was the natural state of things.

Hijikata was one who used to say, that he grew up in an environment where people said, “I’m the son of a buckwheat noodle shop from the Northeast, bring me a drink of Japanese sake.” In fact, that wasn’t how he grew up, but his stance was one of pretending that his roots were in the rural Northeast and in materialism. From my viewpoint, Hijikata’s stance was a very European type of heresy. He was very much influenced by Jean Genet and Antonin Artaud and didn’t really like Japanese rural culture. I believe that he went through an early period where he struggled seriously with the decision of whether he should try to make his career one as a writer or pursue dance. That is why the things Hijikata wrote are outstanding examples of surrealism in Japanese. No one can match Hijikata’s writing in works like Yamerumaihime . I don’t think there is anyone who could use words like objet to express aspects of Japanese thought like he did.- So, did you rather feel more of an affinity for Kazuo Ono with his firm Christian faith? You might say that the spiritual world of Kazuo Ono is the force behind physical expression of his dance. I feel that this common ground was a strong bond between you and Ono.

- When I do solo improvisational dance, I am sometimes told that I resemble Kazuo Ono. With regard to aspects like my belief that it is the strength of the spirit that moves the body from within, I feel that, indeed, I am still very much influenced by the three years I spent as an apprentice under master Kazuo Ono.

In contrast, I feel that I learned about choreography from Hijikata. I say learned, but it wasn’t that I actually studied under him as master and apprentice. Hijikata choreographed parts for me in Barairo no Dance – Shibusawa-san no Ie no Ho e and Seiaionchogakushinanzue – Tomato and I believe that the way Hijikata choreographed for me at that time probably became the foundation of my own choreography method.In practical terms the lesson I learned from him was to not make any prior preparations for the choreography. It is a method in which absolutely nothing is decided prior to meeting the dance. Rather, you concentrate on the things you feel intuitively between yourself and the dancer when you begin actual physical movement.In choreography, the important thing is to work with speed and skill, like a sushi chef preparing sashimi (raw fish slices) from fresh fish for a customer. You put the fish on the cutting board, dress it down swiftly, cut it in quick, precise slices and then place it quickly and neatly on the plate. You shouldn’t spend a lot of time thinking about rationalizations or explanations for what you are doing. That kind of choreographic timing that Hijikata had is certainly something that has become engrained in me. So, when I choreograph for dancers, I tend to bring that kind of chef’s speed and skill to the task.- I find it very interesting that the origins of your methodology for choreography go back to Hijikata in the 1960s. However, wouldn’t you say that the fundamental difference between Hijikata and Kazuo Ono was that Hijikata had his own special artifice or strategy when presenting something fresh or raw to the audience? I believe that the prime example of this is his work Twenty-seven Nights for Four Seasons ( Shiki no tame no Nijunanaban ), and it seems to me to be a case not so much of serving up the raw meat quickly and skillfully, he used it to show a new style, or a new convention that was Butoh.

I would like to ask you next what led to your forming your own studio Tenshikan in 1971. It was at a time when Akaji Maro was establishing his own company Dairakudakan and Hijikata was creating the work Twenty-seven Nights for Four Seasons and butoh was beginning to become established as a new form of dance. However, it seems to me that you set off in a different direction and created your studio Tensikan to pursue your own form of dance expression, regardless of whether it was butoh or not.- When Hijikata did Revolt of the Body ( Nikutai no Hanran ) as a solo performance event, I wrote a negative review of it for a magazine, although it was a bit audacious of me. But, rather than getting mad, Hijikata seemed little more than annoyed that I had bothered to write about it. He said, “Kasai, don’t bother with that anymore, I know, that’s enough about that.”

I believe that Hijikata’s representative work wasn’t solo works like Revolt of the Body but his choreographed works like Twenty-seven Nights for Four Seasons . It was the works he had done choreographing for other people all through the 1960s. It was in the DANCE EXPERIENCE performances and Anma and works like Tomato that I performed in. The great thing about Hijikata’s dance was the choreography he did for those works within a carefully conceived composition. That solo performance ( Revolt of the Body ) was the first and the last he ever did. He said, “I’m going to imitate you, Kasai, and do it just once.” That was the kind of attitude he did that one work with.So, what I wrote wasn’t really in criticism, In effect I was saying that Revolt of the Body was interesting as an experiment but I didn’t think it has the essence of Tatsumi Hijikata by any means. It was indeed a bit audacious of me (laughs).- Although you say it wasn’t in criticism, anyone who read it certainly thought it was (laughs). At the time, everyone was surprised that someone that much younger than Hijikata would write such a clearly critical review.

- It was audacious, but with regard to Kazuo Ono I also said clearly that I didn’t agree with his ideas about creating imagination. Ono is one who wouldn’t move a single step until he had formed a base of imagination. He is one who started with imagination and distilled it down to a few drops of essence, and then he could dance. However, I told him that, personally, I couldn’t follow that image, and that I wanted to create dance based on imagination that was more universal, something more objective that anyone could relate to.

For example, there is a cricket in the palm of his hand and suddenly he envisions the cricket as his mother. I told him that I could understand that well enough, but it is still Master Ono’s own mother and as an image it is too extremely personal. In response to that Master Ono said with a look of consternation, “But imagination is a private, personal thing by nature. There is no such thing as an objective image.In the same way, the poet Kunio Tsukamoto wrote in one of his essays about Tanka poetry that “Imagination is an extremely personal thing, no matter how you look at it.” But, at the same time he said that, “There is objectivity in the fixed-form verse of the Tanka poem.” What I told Ono was that, just as there is the objective convention of the 5-7-5-7-7 syllable verse form in Tanka, I want some form of objectivity in imagination. But, I knew that even if I said that to Ono, he could never understand or accept such a concept. He just looked at me with a perplexed expression.Well, after saying pretentious things like that to both Hijikata and Ono, a certain distance gradually grew between us. Still thinking about what Butoh should be, and also bearing a feeling of self-respect, or pride in the fact that I was the one who had first used the word “butoh,” I then took the initiative and started my studio Tenshikan.- What was your aim when you started Tenshikan?

- That is a very difficult question that I still can’t answer in a word with certainty.

In a political sense, there were political philosophies like that of the “Sekigun” (Red Army) for example at that time, but I believe I was searching for something even more radical. In short, it was a vision of a society that could exist without any sort of social power structure or centralized governing force. In other words, my idea was to create an intellectual anarchism and a corporeal hierarchy. It was a concern for questions like what Ankoku Butoh was or what Modern Dance was. Rather, I was searching for a kind of idealism that was separate from all such things. I also had the feeling that dance could be a better path to the root of things than any form of political or religious thought.- What kind of methodology did you employ at Tenshikan?

- There was just one firm element to my methodology: Don’t teach dance. If I started teaching, that would result in the creation of another form of central authority. I didn’t want that. I wanted everyone to do what they wanted to do. For seven years, I provided a place for arts and cultural activity in a state of anarchy completely free of any central authority. After defying Hijikata and Ono and starting Tenshikan, the one thing I thought I could or should do was to provide a place [for people to work and interact]. I wanted something to grow starting from absolute zero. So, I never had the intention of teaching people what Hijikata or what Ono did. My only desire was to provide a place where people who wanted to dance could dance freely and open to the changing winds of the times. The artists who flourished in that environment were people like Setsuko Yamada, Kota Yamazaki and Masahide Omori. At the time there were many people who needed that kind of space with complete freedom.

- I think it is quite amazing that a place for free creative work like Tenshikan could have continued for years in the Japanese dance world back in the 1970s, and I believe it was a dance space unique unto itself. I am certain that, from the standpoint of development of modern dance, and also from the development of butoh from the early half of the 1960s, it was unique and it must have been a completely new type of creative space. Nonetheless, at the end of the 1970s you shut it down completely and took your whole family and moved to Germany. Why was that? Was it to study the thought of Rudolf Steiner and German philosophy?

- I really feel bad about what I did (laughs). I had been talking all the time about anarchism and hierarchy and then one day I suddenly threw it all away and left. Everyone involved was angry, I’ll tell you. It wasn’t really that I wanted to study Steiner more thoroughly, or German philosophy or such. In the end, I just wanted to get to the true “core” in the roots of European culture that no Japanese had yet come in contact with.

If you ask what that core is, it is difficult to put in words. European culture is philosophy and literature and dualism, at the deepest level there is a clear methodology that involves reunifying things that have at one point been completely divided. For example, the fourth movement of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and the way it brings together light and darkness into one. What makes Europe amazing is its ability to bring together two peoples that have once been split completely apart, like oil and water, and then generate tremendous energy from their reunification, like the clashing atomic particles of a hydrogen bomb. The Japanese don’t know this way of creating energy. The Japanese have been monistic from the beginning, with heaven and earth, man and woman always joined as a single flow. What I wanted in dance was the kind of energy that comes from taking things like light and darkness, or oxygen and hydrogen, completely separating them once and then forcing them together again―though not necessarily like a hydrogen bomb.- So, you found a deep, hard to recognize root in European culture that emerged on the other side of the dualist division of mind and body that had existed since Descartes. Is that correct?

- That’s right. And one manifestation of it is Rudolf Steiner. The tragedy of a European people unable to shake off the dualism of Descartes and the people like Beethoven, Mozart and Steiner who created works that raged against it. I believe that when I deserted the people of Tenshikan and went off to Germany it was out of a desire to identify that core in an experiential way with my own body.

- What do you feel is the biggest thing you gained from your six years in Germany? Did you eventually find that fundamental core of sorts that transcended dualism?

- When I first went to Germany, I feel that I was still not fully recognizing the power of words. I think that the most fundamental power of words is, for example with the works sea, it is not the meaning of the word, but the fact that the word can create a sea [in one’s mind]. In other words, the entire “external world” exists within the human body, and it is words that bring it to life [within us]. It was during my time in Germany, I believe, that I truly came to feel that power of words. And, it is surely something that is awakened within the concepts

- But, without ever going to Germany, when I read things like Hijikata’s Ailing Dancer ( Yameru Maihime ) or your Tenshi-ron (Angel Theory), I feel already the existence of words that are used as a sort of catalyst that induces reactions in the body, words causing a sort of chemical reaction with the power they contain.

- It is indeed true that I had very real experiences of the creative power of words before going to Germany. However, it was still only within the realm of my own experience. In the experiential realm, one can know a feeling of a monistic connection of human beings to the things around them, as in a pantheistic concept, or of a unified world in a mystic sense, but I wanted to be able to explain it into words. If you can put it in words, you can communicate it to others.

- You returned to Japan from Germany in 1986, and it was with Seraphita in 1994 that you made you return to the dance world. What were you going during the 7-year blank in between? Some time during the latter half of the ’80s I attended a talk at Studio 200 in the Ikebukuro district of Tokyo where you spoke passionately about Steiner’s thought and Eurythmy, and you did a demonstration of Eurythmy movement.

- After coming back from Germany, I was doing anthroposophy all the time. At Studio 200 there was a sort of anthroposophy community, like an inner circle of friends that I talked to. It wasn’t that I was fully absorbed in it, but it was about the only connection I felt to Japan. I couldn’t think of myself as Japanese anymore, and there was a strong feeling within me of being a foreigner in my own country.

Part of it was the result of the economic “bubble” at the time. When I returned to Japan, the whole country seemed to be caught up in the bubble and I was close to being in a state of depression. Within that kind of atmosphere, I couldn’t even begin to think about creating and presenting works, and I didn’t have any desire at all to go and see other people’s dance. It turns out that, including the time in Germany, I lived for 15 years without really being active in the society. The first real social action I took, in that sense, began after Seraphita, I believe.- After that long, long blank period, you returned to the Japanese dance world in 1994. What was it that made you decide to become active again?

- The reason that I was able to spend seven years in Germany with my family of five without working for a living was because I was supported by a sort of communal framework. After returning to Japan as well, I found no place for myself in the bubble society and eventually I was only able to be active within a closed community. However, true cultural activity cannot exist within the confines of one particular community, so I decided that I had to go out into the society at large. My first step to go out into society again was Seraphita .

- What is the principal aim in your activities in Tenshikan today?

- One thing that remains the same with Tensikan before I went to Germany is that there is no organizational structure. The atmosphere is one of freedom within anarchy, but one thing we do strictly is training of the body.

One of the methods for this is Eurythmy. There are four basic bodies that every human being has. The body before conception, the fetal body before birth, the infant body during the period when the child is absorbing its mother language, and then the adult body. The adult body and the body that is shaped by the absorbing of language up until the age of three are completely different. Also, the fetal body is truly amazing. In the same sense, there is the body after death. Not just as an image, but as a fact that the dead have a body of the dead. Connecting these different bodies is the fundamental concept behind the physical training we do at Tenshikan.In practical terms, one of the forms of training is to read passages in Japanese while moving the body and listening with full concentration. Simply it involves listening as hard as you can. Then, we practice the enunciation of vowels and consonants. For example, the “ah” sound is pronounced from deep in the throat, the “oo” sound is made by shaping the lips in a “u” shape, and for the “eh” sound the tongue is used. Each sound is pronounced in precisely, one by one, and then repeated. Using the Eurythmy method, the reverberation of the sound of the words is listened to with the whole body as you move. Normally, until the age of three children don’t form memories, and that is the period when the mother tongue is absorbed. It is “the body without memories.” We practice to return to that stage of the body.- I heard that you taught dancers in a workshop in Angers, France for about a month. What kinds of things do you teach besides the four stages of the body?

- It is extremely simple things. We practice physical awareness, in things such as how the body changes when you are on the streets of the city. It is a process of renewing awareness of sensibilities related to the body. There are basically two ways to train the body. One is to build physical strength by working hard lifting barbell or doing push-ups. The other is to train the body by reaching realizations through awareness. Sometimes this latter brings bigger changes to the body. Learning things through awareness brings great changes to the body.

- Does that mean you can change a person’s body through deliberate use of words?

- It is not a matter of understanding the meaning of words, but one of using the power of words as food for imagination, that will bring change to the body. One thing I have in common with Hijikata is using words to arouse primordial essence in the body. Ono used the powers of imagination to create dance, but the ability to do that is surely one of the points of divergence in dance.

- Your work Kafun Kakumei (Pollen Revolution) (*3) has been performed in several countries. Did the different dancers (and their bodies) that you encountered in staging those performances have an effect on your views regarding the body and choreography?

- For example, this is true when choreographing works in different cultural settings like New York or France, the country where a work is performed always creates big differences. Because the way the audience views the work will be completely different. For example, for the work Das Schinkiro that I created and staged in Germany, the dancers were all of different nationalities. Those differences naturally come out in the choreography, but the German audiences that view the work are not necessarily look for the differences in nationality. In Japan, however, the audience looks at the national differences immediately, but European audiences aren’t concerned with that at all. For them, the things that the work is trying to explore are the important thing. And, conversely, if you showed concern for the nationalities involved, it would be considered rather strange. It is the same with gender differences. In Germany, men and women will be standing around naked in the same changing room conversing normally and nobody thinks it strange. Theirs is a type of globalism that ignores differences in gender, nationality and generation differences. In short, it is an approach that sees the artists purely as human resources. I sense very strongly that the trend in works today is toward one of two types: works that are created with the aim of placing the most value possible on the differences and the individuality of each person involved in the context of global culture, and a second type that uses a colder approach that use people purely as [material] resources.

When globalism began to enter dance around 2000, there was definitely a period when the Japanese began to see abstract dance that transcended differences of gender and nationality as something avant-garde and fresh. That also meant that they were stimulated by things like the early works of Forsythe. However, when it comes to creating works, I just can’t bring myself to see the dancers merely as resources. Instead, I want to spend time getting to know in detail what kind of person the dancer is, man or woman, what their nationality is and how they were raised. However, I do sometimes become curious about what kind of work would result if I did away with all that and took an abstract approach that looked at each person as simply another dancer.- What are your plans for activities overseas in 2013?

- From January I will be in Angers and Saint-Nazaire in France for a month to create and perform a duo piece with Emmanuelle Huynh titled SPIEL/Yugi . In May we will be performing that same piece in Japan.

- Do you have any plans in the future to work in collaboration with from other genre like contemporary composers and visual artists? And, what is the reason that you have not done much in that direction until now?

- I guess it is because the majority of my images tend to be a music-oriented, while on the other hand I tend to be weak in the area of visual or material images, and so it is true that I have worked mostly with musicians like Yuji Takahashi. However, if the opportunities arise, I would also like to try working with contemporary visual artists.

In fact, there is a German artist named Anselm Kiefer whose works I have long wanted to try using in combination with my dance. Kiefer is an artist who goes beyond the tableau context and creates works in which taking a new approach to the material he works with succeeds in changing the very nature of the material. He can take something like a factory and turn it into a work of art, or make a work out of a hole he has dug, so I am interested to see what would result if I were to work with some objet works he supplied me with.I would also like to have the Japanese painter Fuyuko Matsui do some stage art for me. Matsui-san paints ghostly figures, but rather than saying she paints them, it is more like the works actually become ghosts. Although her medium is traditional Japanese Nihon-ga painting, she creates something very new.- Are there any other new things that you would like to try in the future?

- Although it is just a vague idea, I am thinking about what would happen if I created an all female version of would like Hayasasurahime . The reason is that, because of my dancer-oriented approach and because of the fact that a man’s body and a woman’s body are so very different, when I create a work I am very concerned about that point.

With Hayasasurahime I was very conscious of creating a work for men, so I am thinking about the questions of what kind of work it would become if I created it again for women.- Finally, I would like to say that I and many like me will be looking forward to your new challenges in the future. Thank you for giving us so much of your time for this interview.

*1

Tenshikan is the name of a studio Kasai opened in 1971. The name means the building of angles and it is taken from the famous Castle Sant’Angelo in Rome. Kasai chose it as the name for a studio for study of techniques for approaching the human body because of its namesake’s history as an old prison that became a museum for art of Manierisme.*2

The performance of the work Seraphita – Kagami no Seiki wo Motsu Watashi no Onna at the Nakano Zero Hall in January 1994 was Kasai’s first butoh performance in 15 years. Among the performers were former Tenshikan members Setsuko Yamada and Josaku Sugita. It was a mysterious work in which Kasai exuded a hermaphroditic aspect with great appeal for the fans who had long been awaiting his return to the dance world.

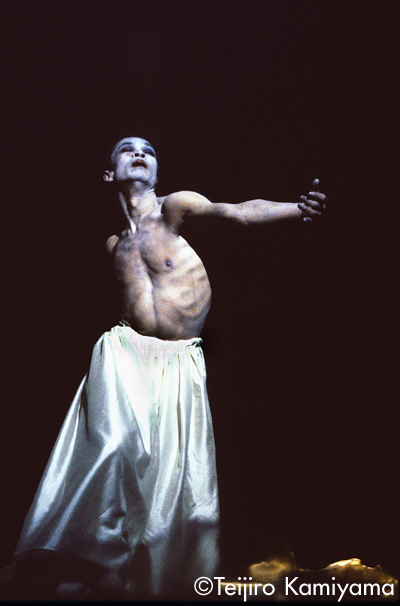

Photo: Teijiro Kamiyama

*3

Kafun Kakumei (Pollen Revolution) is a representative solo piece in Kasai’s oeuvre. It premiered in 2002 as a work in the solo dance series of Theatre Tram (Setagaya Public Theatre, Tokyo) and has since toured to several dozen cities around the world. Wearing the headpiece and kimono of the famous Kabuki role Musume Dojoji role, he dances to part of a woman falling into a state of love madness.

(2002 at Festival International Cervantino, Mexico)

Photo: Christa Cowrie

Akira Kasai x Akaji Maro

Hayasasurahime

(Nov. 29 – Dec. 2, at Setagaya Public Theatre)

Concept, Direction, Choreography: Akira Kasai

Artistic Adviser: Akaji Maro

Photo: Teijiro KamiyamaRelated Tags

- In the choreographic theme of your work Hayasasurahime this time, I certainly felt a bacchanal element. What’s more, I also felt great appeal in the intellectual bearing of the composition that suggested an apollonian aspect as well. However, despite that, the choreography didn’t appear to be something you created in a calculated way. Rather, it had the appearance of choreography that created itself freely.

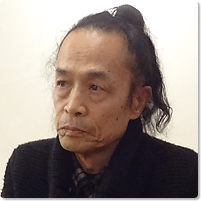

Akira Kasai

A look into the choreographic art of Akira Kasai, fifty years after entering the world of Butoh

Akira Kasai

Akira Kasai became active as a Butoh dancer after meeting Kazuo Ono in 1963 and Tatsumi Hijikata in 1964. By 1971, at the age of 28, he started his own studio Tenshikan (*1). From this studio would emerge Butoh artists Setsuko Yamada, Kota Yamazaki and others. In 1972, Kasai traveled to Germany and studied at the Eurythmy school in Stuttgart. After returning to Japan in 1985 he lectured on the anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner and held performances and workshops on Eurythmy. In 1994, Kasai made his return to Japan’s dance world with a work titled Seraphita (*2), after which he continued to present not only his own solo pieces as well as choreographing pieces for such representative butoh artists of Japan’s contemporary dance scene as Kuniko Kisanuki, Kim Ito, Naoko Shirakawa and Ikuyo Kuroda, and also figures like the famed ballet dancer Farouk Ruzimatov. At the same time he has also performed actively overseas in places like North and South America, Europe and South Korea.

Kasai has proven himself to be a unique figure of amazing and inexhaustible artistic creativity, working with equal ease in butoh, modern dance, contemporary dance and Eurythmy, as a butoh artist and choreographer. In this interview we ask Kasai anew about the foundations of his work and thought.

Interviewer: Tatsuro Ishii, dance critic