- Sankai Juku first went to Europe in 1980, and two years later in 1982 you had already received an offer by Théâtre de la Ville, Paris to co-produce your new works. At the time you must have been surprised by the boldness of such a grand offer to a young private company coming out of the Far East.

-

I still remember very well the day I received that offer. In fact it was in 1981. The Director of the Théâtre de la Ville, Paris, Gerard Violette, came with a consultant, the late Thomas Erdos, to the theater in Lyons where we were performing

Kinkan Shonen. Their offer was for us to perform

Kinkan Shonen

and one more new work. The new work was of course to be a co-production with the Théâtre de la Ville, Paris. But—and thinking back now this is really laughable—I didn’t even know much about the Théâtre de la Ville, Paris at that time, so I told them I wanted some time to think about their offer. Years later, Violette told me that I was the first one who had ever told him I needed time to think about a commission offer from Théâtre de la Ville, Paris.

Looking back now, I never imagined that our co-productions with Théâtre de la Ville, Paris would continue this long. There have now been 12 works produced there in 26 years, and to be honest, I don’t think that all of them were great successes. Still, they continued to offer the commissions, and for that consistency I am truly grateful to Mr. Violette. By continuing to offer those commissions, he gave the support that we needed to develop as a private company without any base of our own. Honestly speaking, I doubt that Sankai Juku would still exist today were it not for Théâtre de la Ville, Paris and the rest of the French arts support system. Although it is mere speculation, I would say that if I had not made that decision to go to France in 1980 but had stay in Japan and tried to continue my career there, I might have given up on dance early on. - Mr. Violette retired last year, and he has been replaced by a young director from theater in his 30s. Will this change the relationship between Théâtre de la Ville, Paris and Sankai Juku?

-

At this point, we are still scheduled to produce a new work for the 2010 spring season. And fortunately, I feel that we will be able to continue our co-production relationship under the new director, Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota. However, it is not as if we have a franchise contract with the Theatre, and there have never been any guarantees concerning future, not in the past or from now on. It is always a matter of objective judgment on the part the director after seeing the results of each new creation the artists present.

Those judgments are not made on the basis of any personal relationships with the artists involved. No matter how long a relationship of co-productions may have continued, if the latest production is definitely not up to the Theatre’s standard of quality, there will be no new commission. In fact, I know of several young companies that have received commissions from Théâtre de la Ville, Paris but were not able to present works that lived up to the Theatre’s expectations and, as a result, there was no new offer after that. It all depends on the quality of the works. It is a severe and clearly defined world. - That places a lot of responsibility on the director who makes those decisions.

-

That’s true. And that is why they place extreme importance on going to performances to see, to listen and to meet artists. They believe in their responsibility as professionals and trust their own eyes and ears to find works that they are truly convinced have the quality required for their programs. In light of this, I believe it is truly meaningful that Sankai Juku has been able to continue its series of world premieres of new works at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris since 1982. No matter how outstanding your works may be, it is still difficult for performing arts staged in the Far East to be noticed by European directors. It believe that it is only because we have had the opportunity to perform our works regularly in Paris that Sankai Juku has been able to find venues for our performances all over the world.

It should also be noted that the theaters in France, regardless of whether they are in Paris or the provinces, they are all supported by the taxpayers. So, if a theater continues to present works that are not up to par, the director becomes the subject of criticism from the audience. There is a clear system of responsibility in France. You have the artists who create works, directors who judge their worthiness and the audience who decide whether or not they like what is presented to them. And for that reason, I believe that I have been able to focus on what I should be doing as a creator, which is to concentrate on my art without the distractions involved in the difficulties of bringing it to the audience. - The work Kinkan Shonen that you performed most often in Europe at that time involved a solo part where you dance holding a live peacock and stage art that included a wall with a thousand and more tuna tails nailed to it and numerous other unprecedented devices. How did professionals in the European dance world react when they first saw Sankai Juku’s performances?

-

In France at the time, the format for contemporary dance was mainly a series of separate pieces of about 15 minutes each that were strung together in a suite-like form, which was basically the style of “Modern dance.” What suddenly emerged in contrast to that in Germany at the time was Pina Bausch’s “Dance Theatre.” She introduced a form that was completely new, something that had not existed before in the dance world, characterized by full sets of stage art and long, continuous works that often ran for two or three hours.

It was just around the time of this emergence when we first performed at the Nancy Festival in 1980, and in one of the first interviews I was asked if our dance was close to Dance Theatre. It was true in some respects that Sankai Juku’s works resembled Dance Theater, in that we made full use of stage art and designed spaces, and also that one work lasted a couple of hours. However, my approach to dance was different from Pina’s. My point of departure was definitely butoh. So, after that, whenever I was asked that question in interviews, I made a point of bringing up the names of the founders of butoh, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ono, and saying that what I am doing is “Butoh.” - That belief of yours and the performances of Sankai Juku quickly spread the Japanese word Butoh throughout the world. Nonetheless, there were critics in Japan for a while who were saying that “Sankai Juku [work] is not butoh.”

-

Yes, I was often told that by critics around the middle of the 1980s. But I never once called my dance anything other than butoh. The reason for that is because the initial impression, or inspiration, that prompted me to create works came from the influence my butoh predecessors. And I believed that fact justified my calling it butoh. That said, however, I never tried to imitate the conventions or the specific forms of the butoh of Hijikata or Ono.

It is especially significant, I believe, that when I first went to Europe in 1980, there was a period of one full year when, of necessity, I had no news whatsoever about what was going on in Japan. And I feel now that that period was an important opportunity for me to think about what butoh was to me. When I was interviewed in Europe at that time, I was often asked not about butoh in general but about what butoh meant to me personally. That caused me to realize that the reason I could only speak in vague terms about butoh, and not in a way that was convincing to the interviewers, was because I had not really defined within myself what butoh meant to me. So, just as the founders of butoh had created their own completely new “receptacle” for creativity called butoh, I decided that I had to think carefully and define my own form of butoh, my own conception of what butoh should be, that involved a methodology which was free of any simple use of already existing information, free of simple “quotation” of forms that already existed. This was in fact something very close to defining a methodology for the creative process itself. - And what is the personal conception of “what Butoh is” that you arrived at?

-

This may actually closer to a definition of what creation is rather than what Butoh is, but after leaving Japan and looking at things anew, I became extremely conscious of the importance of what I call “difference and universality” in culture.

As we toured the world performing, every city we went to was different in terms of language, food, daily life customs and all. We were drenched in a shower of differences almost every day. And, in the process I realized that culture exists exactly because of these differences. At the same time, on the other extreme there grew in me a heightened consciousness that there is a human “universality” that exists in all people, regardless of nationality or culture.

This universality might also be called the “original form of emotions” or “primitive impulse.” It is the patterns on ancient pots, it is ancient murals, it is what Taro Okamoto called the “archeologics” of culture and there is a common denominator to be found there no matter whether it is in Europe or South America or Asia. You will find it in the similarities of the myths about resurrection from the underworld that exist in so many regions of the world, in the general likeness between the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice and the Japanese tale of Izanagi and Izanami. It seems that when people confront the natural world, they get the same types of creative impulses—those are the types of thoughts that took shape in my mind.

Looking back now, I feel that those personal experiences of universality are the backbone that has enabled me to create and present my works to the world, or perhaps you could say they gave me the courage to work as I have. - So, with that courage you have gained from the experience of universality, you have continued to create and present new works at the Théâtre de la Ville, Paris over the years. They have included marvelous works like UNETSU – The Egg stands out of Curiosity (1986), in which a single thread of water falls constantly from the sky to the earth, and HIBIKI – Resonance from Far Away (1998), where the entire stage floor is covered with sand and 13 round pools of water. These are works that are outstanding not only for their choreography but also the stage art. I have heard that you said the encounter with the Théâtre de la Ville changed you consciousness of the floor in your works.

- Yes, that is true. The Théâtre de la Ville is designed so that the audience looks down on the stage, much like the outdoor theaters of ancient Greece. My encounter with this theater changed my way of thinking about the role of the floor surface. Seeing the stage floor of the Théâtre de la Ville spread out before the eyes, I felt a definite consciousness residing in it. After that, I was never able to ignore the role of the floor again, and it became an artistic material that I used very carefully and consciously in my creative process. For example, if you take the work TOKI – A Moment in the Weave of Time (2005), where I spread a thin layer of sand across the entire floor, it is easy to understand how in many Sankai Juku works the floor surface changes with the passage of time. And by the end of an hour and a half or so of dance, the footprints left by the dancers in various strengths cause a kind of large picture to take shape. At this point in my career, I have come to think of this large stage-floor picture created by the footprints one essential part of my butoh works.

- Taking that into consideration, can I ask you again how you would express what Butoh is to you?

-

Whenever I am asked that question, I answer that my butoh is a “dialogue with gravity.” This is a dialogue that people of any country should be able to understand, with very little difference in how they experience it. That is because, in addition to the universality of emotions that I mentioned earlier, there is also a “universality of the body” that all humans share.

For example we speak about the repetition of ontogeny and phylogeny, and when an individual is born, no matter what country they may be born in, we all born as inheritors of DNA that has been through the same stages of the human race’s evolution. Fish evolved into amphibians and amphibians into mammals, and as humans we began to walk the earth. We are all born with bodies into this same path of phylogeny. And the life that is nurtured in the amniotic fluid of the mother’s womb and born into the world, then goes through the same process of taking about a year to gradually learn to stand. Whether it is a Caucasian or a Mongoloid, all humans go through the same process. In other words all humans have a certain physical universality in common and everyone begins the dialogue with gravity from birth and learn through it to stand and walk. And I believe this dialogue with gravity to be an essential element of butoh. - It may be that all people learn to stand thought their initial dialogue with gravity, but not everyone can dance as a butoh dancer. How do you train a “body in dialogue with gravity” that is worthy of being seen on stage?

-

A body that is completely relaxed is a body that is lying down, right? I begin first of all with this easiest of states and then take the body through the process of sitting up and then standing as the fundamental form of body in dialogue with gravity. While doing this, attention I focused on applying the absolute “minimum strength necessary.” When in an unconscious state, the body naturally resorts to patterns of movement it already knows. Lesser instincts go to work and unnecessary tensions naturally come into the body. My job is to carefully and consciously have the dancer identify and remove these tensions one by one in order to create a body that can conduct the dialogue with gravity in the most straightforward and unaffected way.

For example, our arms are attached in a way that they hang from the torso, so if we perform the action of lying down the arms should normally just collapse along with the torso as it lies down. But in actuality, unnecessary forces come into play and the arms make preemptory movements. I call this a condition where the dialogue with gravity is broken. When this happens, I carefully note for them where the unnecessary tension has come into play.

The image of a body in which the dialogue with gravity is going well is one that, when standing up, has the center axis of the body is pointing straight toward the center of the earth. In other words, the force of gravity is distributed evenly on the bottoms of the two feet and the body is standing very easily. This is the ideal primary form. Then, from this straight-standing basic posture, the hips should ideally be lowered and the act of walking begun easily on the heels. If the position of the hips, or pelvis is too high, there is unnecessary tension at play, like in a ballet suat? In our case, unlike in Western dance, we lower the hips instead of raising them to achieve a basic posture for the body. - The way of thinking about tension then is different between Western dance and butoh. Is that correct?

-

Yes. Most Western dance is created by tension. Raising one leg and holding it up, or controlling a particular form. The foundation for movement is tension. In contrast, we think of the relaxed state as the base of our dance. It is the act of relaxing for an instant that enables a shift of the body’s weight from the right leg to the left leg, and if you can’t perform that shift of the body’s center of gravity, you can’t take a single step. In other words, the relaxed state is in fact the base and from there it is a question of how much tension is applied. I believe that the process of paying careful attention to that relaxed state and the deliberate and measured application of tension is what makes a body able to understand and dance butoh.

Naturally the movement becomes slow. After achieving an initial relaxed state, It is then a question of how you interact with gravity. If you try to move without breaking that “thread of consciousness” your movement naturally becomes gentle and slow. It seems that many people wonder why butoh movement has to be so slow-motion, but to me that slowness is a necessity. When you are attempting to engage in an attentive dialogue with gravity it naturally takes on that kind of posture and movement. - In short, the act of moving while maintaining that unbroken “thread of consciousness” naturally leads to slower movement. Is that right?

-

Yes. That’s right. You could say that all of the Sankai Juku choreography depends on whether or not you can keep that “thread of consciousness” unbroken. If that threat is broken it all becomes nothing more than exercise, or simple physical movement.

For example, once the dancers are out on the stage, outside of them is no longer an ordinary daily-life space. Rather it becomes some type of “assumed external environment” such as the universe, the underwater world or perhaps a seashore. In other words, by interacting with the light, vibrations of sound or the space itself with a particular consciousness, we are attempting to project into the minds of the audience a virtual space and time experience.

Furthermore, the dancers have their own intensive internal involvement that must not be broken. What the dancer is feeling internally at the moment may be fear or hope. And if you are able to pursue that feeling intently, without losing the thread, your movement will follow in suit naturally.

In short, Sankai Juku’s choreography consciousness always precedes form. Focusing the consciousness on the external environment and/or the internal changes gives birth to rightness of movement. That is why there is not a single mirror in our rehearsal studio, which might otherwise be used for checking the beauty of mere form. - That means that as the external environment that leads the dancer’s internal consciousness, the stage art, music and costumes must also achieve a very exacting level of artistic completion, doesn’t it?

- As you say, for me the lighting, music and stage art are equally important elements along with the dancer’s movement. Because they are means that are used to help create that invisible “something” we give expression to on the stage. This may be a rather abstract way of describing it, but I think in terms of a sort of “bridge” that is strung between us dancers, and the audience. And the among the elements used to create that “something” in the time-space of that bridge are the stage art, music and the movements of the dancers. It is not the case that the movement of the dancers is the “main” element and the music and stage art a “sub” elements, rather they are all three “sub” elements supporting the invisible bridge between us and the audience. And the important thing is that this “something” is created and appears in each performance. That said, however, there are definitely times when that process is successful and other times when it does not succeed as well.

- Since that invisible “something” cannot be seen, we wonder how you reach consensus with the other dancers.

-

Well, I would say that “consensus” is something that is reached gradually in the rehearsal [practice] studio. When I begin working with the dancers on a new piece, on our first day together I start with a short lecture on what I want to do in the new piece. And once I have communicated in that way my general idea, then we begin working on the actual physical movements, which I call “Trial #1.” The Sankai Juku dancers are of course thoroughly familiar with this process now, so when I say, “OK, let’s start Trial #1,” they know what it means. And they know that then it changes and develops naturally from there to #2 and #3. That process is repeated over and over with concentration by the dancers in the studio until a consensus is reached, or until I myself am convinced that something is right. There are times when everything goes well from the start and a five minute scene may be worked out to successfully in the course of one day in the studio, but at other time we may spend a whole day working and not even one minute of a scene is worked up to satisfaction. Still, the Sankai Juku must have the patience and the concentration to keep focused internally and keep working like that in a studio with no mirrors or music.

Through this careful and patient exchange, consensus is gradually reached and the movements of a scene become fixed. In the end, the choreography that we arrive at by this method is so certain that we can time ourselves dancing a particular scene with a stopwatch in a studio with no music and the time will not vary by more than 30 seconds. This precision comes purely from our breathing and our concentration as we dance. If there is a variance of more than 30 seconds, the dancers can feel in their bodies that something is not right. - In 2005, for the first time, you did a re-creation of Kinkan Shonen. This is a work that you originally danced four solo scenes in, but in the re-creation you had several younger dancers do these solos, and you didn’t perform at all in it. Could you tell us in some detail what made you decide to revive the work in that way and whether you were able to achieve a good sense of consensus with the young dancers?

-

The reason I decided to do the re-creation was simply because I had received offers to do it. Even after the 1993 performance of

Kinkan Shonen

at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris, that I decided would be my last, I still received many requests to perform it from different theaters. But this is a work that, physically, is very hard for me to perform anymore. That is why I decided to do a re-creation in which I entrusted that task to the younger, stronger bodies of others.

In the actual work of transcribing the piece, I placed primary importance not on transcribing [physical] forms but on transferring the emotional transitions involved. As we worked, the important thing for me was what the dancer experiences and feels, or perceives, in each movement. As long as there was no discrepancy in that [emotional/perceptive] aspect, I would tend to welcome differences in the actual forms of the movements as a natural expression of individuality consistent with the character of each dancer.

It is certainly true that with the young dancers I used, I could not get the same kind of “consensus” based in close synchronization of breathing and feeling, etc., as easily as I could with the original members of Sankai Juku. When I used the word “chinden” (precipitate, sink), the old members knew immediately from experience what I was talking about. But the young dancers would ask, “What is precipitation?” “Is it different from “falling”?” Being asked those questions made me realize things. They made me realize for example that my own expressions had become codified in a way. In that sense, this re-creation was a very fruitful process for me. - How much time do you spend in the studio preparing a new work? Could you describe the process using the latest work, TOBARI – As If in an Inexhaustible Flux , that you presented in May of 2008 at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris?

-

We spend about two months working up a new piece in the studio. During that time we stop all touring and performances. In the case of TOBARI, we used a studio in Yokohama for the first month of work. Then we moved to Paris and worked in a studio on the upper floor of the Théâtre de la Ville with a stage area the same size as the theater’s actual performance stage. Being able to work in a space with the same dimensions as the actual performance stage is extremely important for the dancers. Because, with the internal tension that is so important in my choreography, differences of, for example, even one step in a sequence can have a slight but perceptible effect on the emotional tension or the thread of concentration involved.

Also, at Théâtre de la Ville they give us access to the actual stage with the theater empty for one week before the opening performance. So we are able to rehearse there with full music, lighting and stage art for the final “trial” stages. Many of the technicians there are the same people I have been working with for the last 26 years, so they understand me when I say “This part is still a work in progress.” So, even after the stage has been set, I can say I want the lighting at this part to be changed and they gladly say, “Sure.” Creation is a process that involves changes right down to the last minute. And so, I am always impressed whenever I work with people who have a professional attitude and strive to understand what I want during the work of mounting a piece. - In Sankai Juku’s case you have your dancers actually involved in the making of the set, props and costumes. Didn’t that bother the foreign theater crews when you first started doing productions overseas?

-

Yes, it did. But with regard to this point, I have deliberately held to the same style of working since the beginnings of Sankai Juku in the 1970s. That’s because I want the dancers to get a firsthand understanding of what goes into creating a stage production. There are many things that the dancers won’t come to see if they are just brought to the stage after all the set preparations have been completed and told to go ahead and dance. For example, in the case of a prop the dancer will be using in the performance, his or her approach to that prop will be different if it is one that they have made with their own hands rather than one somebody else made. By making it themselves, the dancers get a more specific vision of how they should interact with that prop on the stage during the performance.

But, as you said, the foreign theater staffers definitely were surprised at first to see us working on the props and costumes like that. Especially in the U.S. where the unions are powerful and the jobs of each technician are clearly defined. In that environment dancers would normally never be allowed to touch the props backstage. But in the course of a long-term relationship they become more flexible and will say, “We’ll make an exception in your case.” I believe that there is definitely a lot that is gained in that way from continuing a relationship long-term. - Earlier you mentioned that there is no music in your practice studio. Can you tell us about the music production process for your works?

-

Basically, at the same time we are working on the movement in the studio, I am involved in a dialogue with the composer at simultaneously. This process differs slightly depending on who the composer of musician is.

For example, if it is Takashi Kako, it is a process of re-arranging pieces he has already composed, and in that sense it is similar to Western classical dance in that it becomes an approach where you have the basic dance and a “musical text.” In other words, in such a case the music exists from the beginning and the main focus becomes how you approach the existing emotions and poesy in the music. I engage in diligent dialogue with the composer/musician about things like whether we can change the piano to another instrument in a particular part or whether the number of phrases in one section can be doubles in number to lengthen the piece.

In the case of YAS-KAZ, the dialogue usually begins with deciding what instruments will be used. I may say it would be good to use a tabla in this part, or no, it should be an instrument with more tensive strings, or “Why don’t we add a bit of blue electric violin sound here.” So, it is a process focused on the qualities of sound of the instruments to be used.

But whether it is Kako san or YAS-KAZ or Yoichiro Yoshikawa, when the final recording is being made, I make it a point to be there in the recording studio. There at the studio I feel the vibrations of the live sound with my body and think about to what degree it can be used the stage performance. Whether it is music or any other aspect of a stage, I am the type who wants to be directly involved in the production work. It is very interesting to do so, and I learn a lot from it. - About 30 years have passed since you first performance of Kinkan Shonen at the Tokyo Fire Department Hall that made you known. But it seems that you still like to make works from scratch with your fellow artists just like you did back then, don’t you?

-

That’s true. That aspect of my work hasn’t changed much. But in our case it was really that first year in France [in 1980] that made it possible for us to be able to continue working as a company all this time, I believe. We went to France and from the network developed there we were invited by presenters to Belgium, Switzerland and Italy. And things also changed when they wrote about us in

Le Monde

and our name became known widely.

In Europe and in North America, if you have something that you want to express before an audience, no matter what it is, there is an arts organization there to support you. That brings strength and courage to the performers in their creative careers, and it is something we are grateful for. Things have begun to change somewhat in Japan, but there is still not the backbone of support young artists need. So, unfortunately you still see young people of talent going overseas to get that support. I believe that Japan needs to think once again about the significance of this phenomenon. If there is not a non-commercial system of support the balance of culture and the art is thrown off.

Ushio Amagatsu

The unending challenge of butoh artist Ushio Amagatsu, a leader in the international dance scene for over 30 years

©Yuji Arisugawa

Ushio Amagatsu

After going independent from the Dairakudakan butoh dance company led by Akaji Maro in 1975, Ushio Amagatsu formed his own company Sankai Juku. In 1977, this small company with just four male dancers gave their first public performance under the title Amagatsu Sho, and in 1978 presented the work titled Kinkan Shonen (The Kumquat Seed) that would established their name in the dance world. By 1980 they were already giving their first overseas performances in France. In their first year in Europe they won acknowledgement with performances at the Nancy Festival in the spring, the summer Avignon Festival and the autumn Sigma Festival, Bordeaux. With those performances the Sankai Juku name and the term “Butoh” rapidly spread throughout Europe. In 1982 the company entered an agreement with Théâtre de la Ville, Paris to do joint productions of new works. Since then these co-productions have continued at a pace of about one new work produced every two years. Recently, more than a quarter of a century after bursting onto the world dance scene, Sankai Juku was awarded the 2006 Asahi Performing Arts Grand Prix for the work TOKI – A Moment in the Weave of Time and the latest work TOBARI – As If in an Inexhaustible Flux continue to be presented to high acclaim. Until now, Sankai Juku has performed in approximately 700 cities in Europe, Asia, North America and Oceania.

Interviewer: Kyoko Iwaki

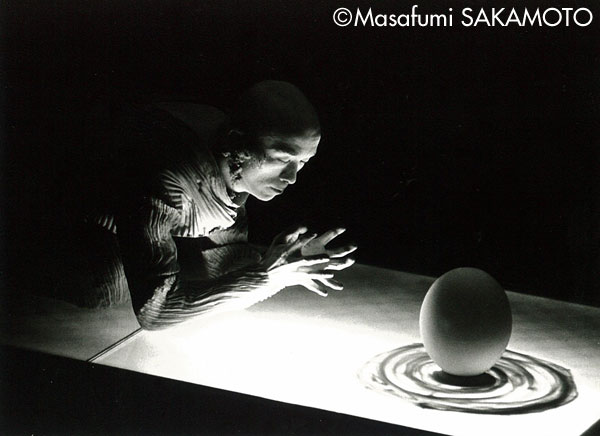

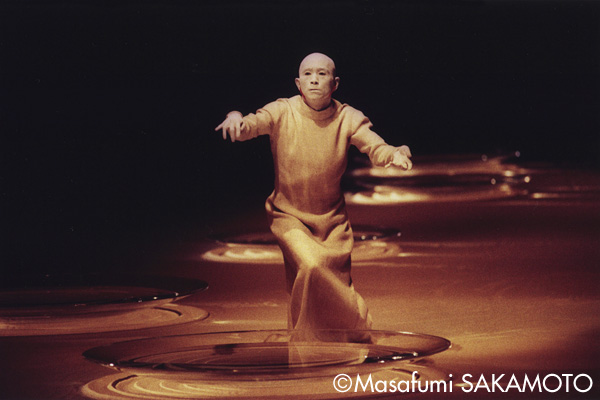

KINKAN SHONEN

Premiere: 1978 at Nihon Shobo Kaikan (Fire Department) Hall, Tokyo

©SANKAI JUKU

©Masafumi SAKAMOTO

©Minako ISHIDA

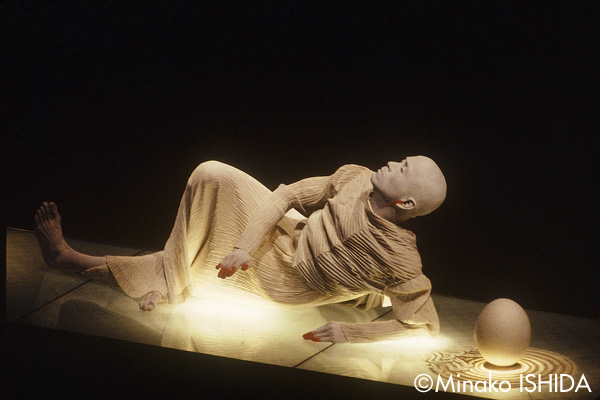

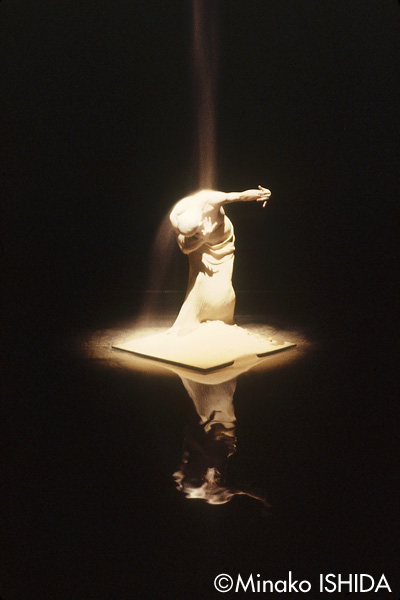

UNETSU – The Egg stands out of Curiosity

Premiere: 1986 at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris

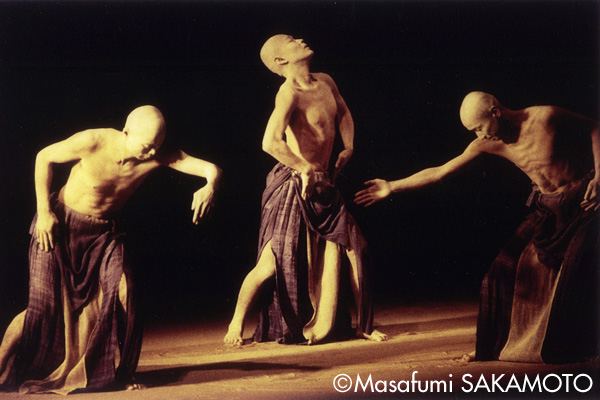

HIBIKI – Resonance from Far Away

Premiere: Dec 1998 at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris

©Masafumi SAKAMOTO

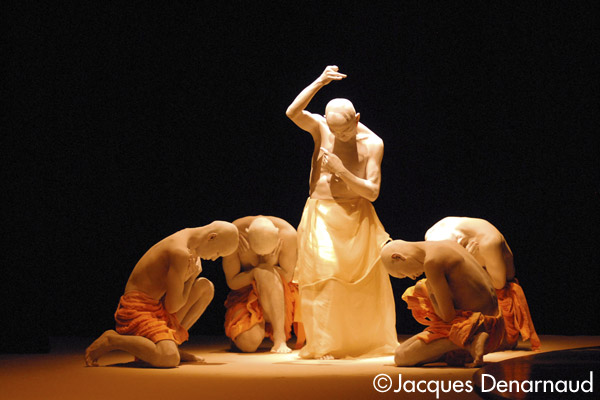

TOKI – A Moment in the Weave Time

Premiere: Dec 2005 at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris

©Jacques Denarnaud

©Jacques Denarnaud

©SANKAI JUKU

TOBARI – As If in an Inexhaustible Flux

Premiere: May 2008 at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris

Related Tags