To Belong – dialogue

- Your work To Belong – dialogue is a collaboration with the Indonesian musician Slamet Gundono and dance artist Martinus Miroto, the Japanese film director Kei Ishikawa and sound designer Yasuhiro Morinaga and others that came together under your directing as a multimedia dance work. And it strongly reflects Indonesian culture that you have been researching for years.

- People tend to associate Indonesia primarily with Bali, but I wanted to show aspects of an Indonesia that is different from the stereotypes many outsiders associate with the country. Even some of my friends asked if the work was going to have Balinese dance or kecak in it, so I wanted to show more diversity in this work.

- That is a difficult aspect of collaborations, isn’t it? You want to show the appeal of the country’s culture, but to some degree it can’t help but be seen as an introduction to the country.

- That’s true, isn’t it? Although it is an international collaboration, I felt that it could be more than just a case of “This is what we can do when our two countries work together.” I felt that there is a need to do a stage where they do their thing as they do it and we do ours and we keep an awareness of our differences but it still comes together as a work. But, that is easier said than done (laughs). It’s strange, isn’t it. Long ago, when I was first beginning dance, I felt it easy to get into European culture, but it wasn’t easy with Asian culture.

- Geographically, Asia is closer but the cultures seen far apart.

-

It seems that the more research I do the more foreign things become and I wonder what they can be (laughs). When I see the steady, unwavering dedication to the traditional dance they have learned, I feel both admiration and a contrary feeling of, “Don’t you ever question things about what you are doing?” (Laughs) What’s more, there are spiritual aspects that come into it naturally on a daily basis. Although it is not based on logic, their dedication is steady and unwavering. That is something that attracted me greatly. Because, there is something in it that I don’t have.

What I was doing with my company Leni-Basso for ten years was exactly a battle against the logic of the European style. All that time, I worked on refining my concepts, with stoic discipline. I always had the belief that something couldn’t be called a work if it didn’t have a clear conceptual essence running through it. But isn’t there a large portion of dance that naturally falls outside the bounds of logic? I began to think that, to begin with, I wasn’t really enjoying what I was doing, and also that I wanted to surprise the audience a convincing power based in chaos [rather than logic].

An Indonesian connection that began from martial arts

- How did the project that produced To Belong get started?

-

Rather than saying that the project was begun to create this work, I feel that the results of continued research over a number of years finally took form in this project. It was a huge project that involved things that I never would have done, never would have allowed myself to do in the past (laughs).

There were several stages involved, beginning with my encounter with the Perisai Diri school of the traditional Indonesian martial arts form called Pencak Silat in 2004. It is primarily a defensive martial art, but there are both offensive and defensive movement forms and they are put together in improvisational movement. I was drawn to the beauty of the movements, the beauty of the turns and the refined set of rules that go with the art. There are about 100 different schools of Silat and some of them are connected to specific faiths or beliefs, but the one I do is a modern school with a clear set of rules. I don’t have any of the schools specific movements appear as they are in To Belong , but I do use some parts of it such as the exchange of energy with the opponent and that type of thing. - Why were you drawn to the traditional martial arts rather than traditional dance?

- In works of my Leni-Basso company such as finks (2001) and Ghostly Round (2005) it was necessary to clarify a number of things in order to create communication between two [dancers’] bodies. In doing that, I found that the martial arts type movement offered effective forms that were quite refined. I practiced a number of other types of martial arts but I found that Silat suited me best. When I saw a 63-year-old Silat master moving quickly through circular movements, I was surprised and at the same time I found it to be dance-like. I was also drawn to the techniques used for achieving a sense of speed and power and the way the practitioner could synchronize his movements with those of his opponent.

- I find it interesting that a martial art, which inherently is used for the purpose of efficiently taking down an opponent, should approach dance-like movement, which inherently would contain an excess of what might be considered superfluous movement that fulfills no such specific purpose. Forms or patterns of movement are the result of condensing systems of the types of energy you direct through the body and the way you direct it. It may be drawn from a philosophy, or culture or from daily life, may it not? And, to that enters certain artistic (and therefore cultural) value systems, such as which [movement] feels better or looks better. Traditional dance is the accumulation of those values over long periods of time, and is the same true of the beauty found in the moves (forms of movement) in martial arts?

- Well, yes. In Indonesia there are many people who practice both dance and a martial art. So, my interest in Indonesia that began from Silat led me to visit the country. I went there originally to do research as part of my work at Shinshu University, where I teach, and as I traveled around doing research I was also looking for artists I could work on a collaboration with. Among the requirements for such artists was that we speak a common language (English), and that be artists who had mastered a traditional art but were also interested in seeking new forms of expression. I also wanted them to be people who were fairly well along in years, and in this search I met Martinus Miroto. He is famous in Indonesia both in the areas of traditional dance and contemporary dance, and he has a career of performance in Europe as well. And, he is also an artist who wants to do new things.

- Did you hold auditions in Indonesia?

-

No. I went to personally visit each dancer, and they ranged in age from their late 20s to dancers in their 60s. I was very kindly helped by a number of people [in seeking out artists] including the artistic director of Salihara Theater (Komunistas Salihara), where with Leni-Basso I had performed at the theater’s opening, and people at the Kelola Foundation and people at the Japan Foundation. Particularly the people at the Japan Foundation were very knowledgeable about dance in Indonesia and they gave me lots of information to work from. From what they told me, I learned that there were more dancers on Java than on Bali who would share my interests and intentions.

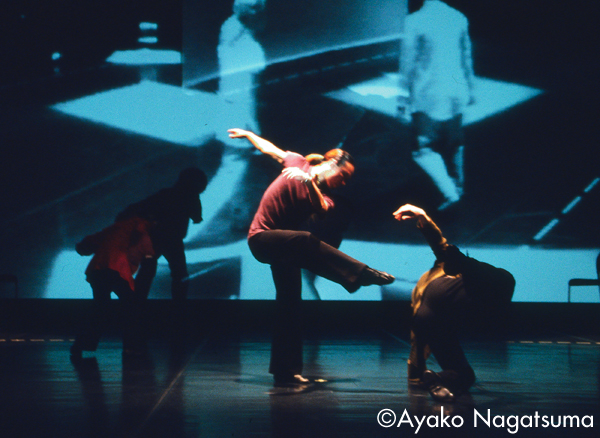

In March of 2010, I got some grant money and was able to start the project in earnest. Since way back in my career I have had the practice of creating compositional charts for all the participating artists in a project to work from. I create charts for about six scenes, like act 1, act 2, etc. for everyone to share and work from. Until Miroto was able to come to Japan, we had to work long-distance, so we depended completely on the compositional charts and Skype. I was able to invite Miroto to Japan in March of 2012 and we did a performance as a work-in-progress, then in April we did a stage performance of it with the title To Belong, and finally in September we performed To Belong – dialogue . - I saw the first work-in-progress and it was quite a thrilling event, wasn’t it? (Laughs) You were all there on stage and clearly searching for ways to proceed, saying, “What shall we do here with this part,” and at times Miroto was saying, “No, I don’t want to do that.” (Laughs)

- It was near the point of falling apart, wasn’t it? (Laughs) The staff was new and there were many parts where the work with the dancers wasn’t going well. But, I had decided from the start that that was going to be one of the meaningful parts of this project. Because, with Leni-Basso it had become a group of fellow artists where everyone knew what I wanted and they only gave me the kinds of things that I wanted. That meant that things flowed smoothly and efficiently, but there was also a sense of a closed circle where all the ideas were confined to the same basic framework. So, with the project this time I really wanted the other participants to bring forward things so different that they would have me thinking, “No, please not that!” That is why the apparent discord at that first work-in-progress presentation was, in some sense an essential step in the process.

- So, the result was a work that showed respect for what the Indonesian artists did, while maintaining a certain distance from it, wasn’t it? It wasn’t just a case of loving everything Indonesian, but presenting a work with a sense of distance that recognized the differences and that the interaction was a necessity for both sides. There was also another Indonesian dancer, Rianto. What about the distance with regard to him?

-

He is a dancer who has mastered the traditional Lengger dance form of the Banyumas region, specializing in female roles. He is a person who never says No, and he is always supporting, which has been a big help for me. He has a very strong desire to absorb new things and he will ask me things like, “What is the reason behind this strange type of movement you do?” On the other hand, he brought out a variety of elements for us that would never have come out of me. And the same was true with the Japanese dancers in this project.

The reality that fiction can convey

- How was the performance [ To Belong ] you did in Jakarta after that?

- The audience was very pleased with it and we got some good reviews. Still, it can’t be denied that one appeal was the fresh experience of Japanese dance vocabulary, so we made major revisions for the performances in Japan. To add Japanese dancers in a way that brought out the appeal of the Indonesian dance, I invited some strong and accomplished Japanese dancers to join us, including Masaharu Imazu, Ruri Mito and Yuki Nishiyama.

- The animated video at the beginning was an excellent idea, wasn’t it? The animation shows the musician and traditional Indonesian dalang narration master Slamet Gundono in an animated version with a head that has a zipper that can be opened to enter into his head (laughs). There is also video footage of the real Gundono, and including the animation in the work was a splendid move.

- As the basic framework of this piece I wanted to have the performers enter into the story of a Wayang kulit (traditional Indonesia shadow puppet theater) play. He himself is quite a cute person and his presence brought something I had never had in my compositions in the past, sort of a playful, charming aspect. The film artist Kei Ishikawa had filmed a documentary of Gundono in the woods doing narration and he showed part of it to an illustrator friend and asked him to do drawings for the animation. Then we asked another video artists I knew well from my Leni-Basso period to add graphics to it. All this made it a truly Indonesian style collage. So was the music. The musician/sound artist Yasuhiro Morinaga went to Indonesia to do field work, and he recorded things there like the sound of flies wings and the sound of water rising out of the ground in a spring, and the sound of fish respiration, then he gave that material to another musician to make a musical composition out of it, which was then returned to Morinaga. The final overall direction was done by myself, and it was quite a task.

- In the actual videos I have seen of Gundono his recitation of dalang is calm and seeps into the heart easily.

- What he recites in the piece is about the belief of papa rimo pancha , which says that there are four brothers who constantly protect is and that allows us to dispense with our egos. I is a belief that is found in some parts of Java rather than throughout Indonesia, and if you do a search on it with the Internet you will find very little information about it. But to them it is a very important story. In the history of Java, each influx of peoples from the outside has brought changes in the island’s religion and physical etiquette, but the core of the people’s spirit remains stubbornly and steadfast. The long history of Java has seen the emergence of things like Javanese Hinduism and Javanese Islam, but I have also met artists there who say things like, “Muslims look cool, so they are popular now, but my heart is closer to Buddhism. Gundono says that the true religion of the people comes from the mountains and outside religion comes from outside Java, and that they constitute a duet. There are truly many things that aren’t put into words or into written language.

- In the recent performance there is a dance duet by Rianto and Masaharu Imazu and the final group dance where I felt something like a very large interplay of energy. Within the dances that were very real actions created.

-

Thank you. The duo part was created mostly by the two of them. With the Japanese dancers in the recent performance as well, there were more parts where I left the creation up to them. That was another I challenge I decided to take on.

Of course, the final selection of what parts would be used and the final composition bringing it together was done by me. For example, in the text for the narration about the beliefs of Indonesia, I worked into it a bit of text of my own saying, “I like my own body.” This work [ To Belong ] is no more and no less than Indonesia and Japan as seen through the filter of my perceptions. I have them supply me with beliefs and teachings from Java, but I and the film artists then input our own elements and re-compose it. In that sense, there is naturally a larger amount of fiction in it. But, isn’t one of the important missions of art to depict the truths that can only be communicated through fiction?

Leni-Basso, Berlin and Java

- I would like to ask you to speak a bit more about your own career activities until now. You received a good deal of attention while still quite young, beginning in the 1980s, and in 1994 you gave the opening performance at the new Saitama Arts Theatre as a young artist. You were also a pioneer of contemporary dance deriving from your background in street dance.

- I began to get some attention in dance when I submitted a work for the Tokyo platform of the Les Rencontres Choregraphiques Internationales de Seine-Saint-Denis contest (1994) at the recommendation of the dance critic Masashi Ichikawa, and during that period I was doing a lot of different things. I did things like choreographing a body painting performance and I tried theater-type works. You say street dance, but at the time is was nothing like the cool street dance of today, it was more like a sad imitation of the “Takenoko-zoku” (rock & roll style dance groups). (Laughs) It was a time when even the term “contemporary dance” wasn’t in common use, but I could feel intuitively that on the world dance scene there were new things happening the completely different from the conventional modern dance. Among my friends of the same generation at that time were Ryohei Kondo of Condors, Yuzo Ishiyama of Nest and Chie Ito of Strange Kinoko Dance Co.

- In 1995, you went to Berlin on foreign study fellowship. Seeing your current interest in Indonesia, I wonder what it was that made you choose to go to Germany.

- When I went there it was a few years after the 1990 reunification of East and West Germany and the time when the capital had been moved from Bonn to Berlin. There was a feeling of bustle and excitement throughout the city that I liked. At first I was in what had been West Berlin but later I moved to the eastern part where our studio in a former communist sector building had no central heating, just a coal-burning stove, and I was shivering through the lessons. Old buildings were being torn down one after another and before long a movement emerged to preserve the old buildings, and I could feel the excitement among young artists wondering what the future would bring.

- It was during the “economic bubble” that Japan’s contemporary dance scene became active and exciting, and with all the development going on old sections of the cities were being torn down and new buildings going up everywhere. It is interesting seeing the way the changing cityscape influences artists, isn’t it? When we look at the conditions of the dance world in Germany at the time you went there in 1995, works like William Forsythe’s Eidos: Telos and Pina Bausch’s Danzon had won some degree of recognition and works like these appeared to have broken new ground. The newt year, 1996, the rising dance star Sasha Waltz had presented Avenue of the Astronauts .

- I saw Avenue of the Astronauts at the Dance Platform in Frankfurt. At the time, the reviews said her work was good as entertainment but that it lacked a social message, so I thought things were difficult. At the time, I was very surprised at how much discussion and debate went on even in the dance studios of Berlin. I was doing jazz dance and it was a shock to me when I first encountered butoh (although I didn’t do it myself). I had tried a variety of things in a struggle to find my own style when I was a student, but none of it had felt right. But, I was drawn to the idea of creating dance based on discussion and logic. I found Berlin to be a bit unrefined, but it suited me well.

- Would you tell us something about the unique “grid system” choreography method you had developed at that time?

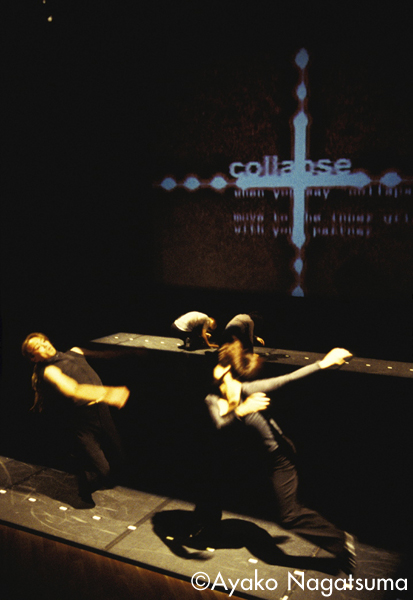

- For some time I had had a vague idea that I wanted to change the relationship between the dancer and the choreographer. I didn’t want to choreograph every bit of the dance, though I didn’t want to leave everything up to the dancer in an improvisational style, so I had long been wondering if there wasn’t a way that I could get the dance to come out naturally by sharing the same ideas with the dancer. I came up with the idea of dividing the dance floor into a grid of squares, set a certain number of rules and have the dancer conform to the rules within the specified positions, and I called this a “grid system” and it was what I used to create pieces like Quarterback Trace (1997) and bittersidewinder (’99). But, when I used the system, what I found out was that to really have it work properly I would probably have to take about 50 years of putting it in practice. (Laughs) So, when I decided to change direction and rather than creating a system I would write down what was necessary for working with the dancers in the studio. The result of that change of approach was finks (2001).

- With Leni-Basso you were also a leader in the use of lighting and video/film. In works like Quarterback Trace , you had an effect like a scanning light running across the stage and the dancers were moving in what appeared to be a state of extreme tension as if the light was chasing and trapping them.

- I like movies, so I’m attracted to the movement of light. Rather than the rich sentiment of the stories in ballet, I wondered if there wasn’t a way to create a type of dance where small impulsive moments of story [narrative] are inserted one after another. People said that it was hard to see the dancers and asked why I couldn’t put lighting on them (laughs). It is because I want to show not only the dance but the space where it takes place in its entirety. In that respect I am grateful to the lighting designer Yuji Sekiguchi who still works with me. Even though we have heated arguments with almost every work. (Laughs)

- Eventually, Leni-Basso came to be known as in Japan as the contemporary dance company doing the most international touring.

- In 1999, I was being invited to a festival in Hong Kong, and in 2001 it was the Bates Dance Festival in America, and I came to realize that in festivals there were these people known as directors and curators (laughs), and as the network grew I was invited to more and more places. It was a time when there was a limited audience in Japan, so I was worried that there was little future for what I was doing. But, the performance environment in Japan, though it can’t compare with that in a lot of European countries, I was to see that it is still better than the sad conditions that exist in a lot of countries overseas where festivals are held. So, I realized it didn’t do much good to complain.

- At that time festivals around the world were building networks and the sharing of information was proceeding at a very fast pace, which was bringing big changes to the ways tours and performances were being decided, wasn’t it?

-

I believe that is true. In the process of a work being introduced to a curator, a lot of changes happen. I realized that dance is not made only by the dance artists. The director of the Julidans Festival in the Netherlands, Jaap Van Baasbank, did a lot for me. In busy months I would be performing in 15 to 20 cities, staying in a bungalow in the Netherlands, I would be working on new works at the same time we were doing those performances. But since we were there as a group [Leni-Basso], the member dancers couldn’t continue their work in Japan. So, the risks were big and it was difficult. I asked for as much support as I could at the time from the Japan Foundation, the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the Saison Foundation. On the other hand, I felt a distance between the work I was doing and the way contemporary dance in Japan was tending toward entertainment. Around that time, I was increasingly busy with overseas touring, and the timing of a number of events led to my taking a position at Shinshu University where I work today.

Teaching at a university

- It surprised us that you could be taking on a teaching job at a university when you were so busy with overseas touring. In this sense of being an active professional dancer who also taught at a university, you were again a progressive leader, weren’t you?

-

To be honest, it was quite difficult balancing the touring and the teaching job. What’s more, at the time taking on a teaching job at a university was considered by many to be the equivalent of retirement as a performing artist, and people began to speak of Leni-Basso as a legend from the past. Even though the truth of the situation was that our increasing number of overseas tours reduced simply our number of performances in Japan (laughs). It made me aware that this truth wasn’t being communicated.

At the time there was also a movement at universities to have students doing things in the field. Since my position is in the Arts Communication Seminar of the Faculty of Arts, there are many students who are interested in dance. As the concept for a classroom course, I try to make it a class that shows that by looking at dance they can see things about Israeli culture, or Indonesian tradition or the excitement of 1960s in America and to show that there are things that can only be seen through dance. Also, there are students who may become interested in the dance costumes and begin to research the history of clothing, so I get them to do research like this in things they become interested in through dance.

Currently, the students are doing independent study based on To Belong and preparing for a performance at a hall. However, I have always had a strong resistance to the idea of getting students involved in my works or activities, and I intentionally kept from doing it. - Isn’t there merit for the students in being able to see the activities of a professionally active artist first-hand, however?

- Lately I have begun to think that there is such an aspect and this time I plan to try having the students do the research and the performance. But, in art there is always the thinking that needs to be done and the practical execution, and at the university I intend to do the thinking side of the artistic creation process thoroughly. If possible, I want not only the universities and the students but also the theaters to become involved actively. There should be more possibilities for tie-ups between universities and theaters, but in actuality there are still few points of contact. Universities are essentially not places for nurturing artists, neither is it a place where we are free to create work after work. Seen from another perspective, for students to experience dealing with issues like how to connect the audience to the artists or planning and implementing projects on the art scene where there are no manuals of best practices is something that will prove valuable in any job they may find themselves in someday, I believe.

- The other day, I was invited to participate in a talk show after a performance by the Inbal Pinto & Avshalom Pollak Dance Company in Matsumoto (where Shinshu Univ. is located) and I was impressed by the fact that such a large number of people of all ages remained to hear the talk in a very warm atmosphere.

- The people of Matsumoto have a very strong interest in the arts and culture. And, the works of Batsheva Dance Company and Inbal make contemporary dance more approachable. The reactions of students are very vivid. If they find something interesting they latch onto it with a passion, but if they don’t they are completely uninterested (laughs). But, being too easy to understand is also a problem. When we were students there was the joy and shock of going to see things we couldn’t understand, but we also felt that there was no need to see things that we already understood. (Laughs)

- After the long process that has produced To Belong , what development do you have planned next?

- The To Belong itself has plans that will continue into 2014, and I plan to continue it after that as well. To 2013, the core of the project has been the collaboration with Indonesia, and next year I will be working on a collaborative work with Yudi Tajudin of Theater Garasi. Some theatrical elements will be added, and rather than being a rearrangement of the work, it will probably end up being virtually an entirely new work. The research and performance with the students that I mentioned earlier will include some of the preparatory work for it, I believe. Furthermore, next year there will be a revised version, or perhaps it should be called a new work, to be performed in Chino city.

- Will your Indonesia research continue?

- Yes. In Indonesia there is the Sunda culture of western Java, the Java culture of central and eastern Java, with differences in each area. On the islands of Java, Bali, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, etc., there is a mosaic of cultural differences, and then there is the area with language deriving from Malay and there is part of the Malay (Melayu) culture to be found there, and every time I encounter their difference the interest doubles. I am interested now in the Sunda music and song of Bali. I haven’t been to Sumatra yet, so that remains an unknown world for me. In the course of my research I have learned about the religious rites and physical technique of the Minangkabau people of western Sumatra that also attracts me. The more I have learned about the Islam and the connections in the customs and physical techniques of each locality, the more I want to keep researching. Concerning Bali, it is fascinating that within Indonesia as a whole, which is 90% Muslim, only Bali has retained ancient rituals that predate the entering of Islam into Indonesia. I want to continue to embrace the sense of “foreign-ness” I find in all of the things I encounter and keep involving with my works and with myself.

- Thank you for your giving us so much of your time for this interview.