- How and when did your encounter with dance occur?

-

In middle school and high school I played in a rock band and in college I majored in sociology, so dance wasn’t a part of my life at all. Up until that time, the only type of physical activity I had done was joining the gymnastics club in middle school. I would go to see things like the one-man theater of Issey Ogata and the Third Theater (

Daisanbutai

) when I was in the university. Then I joined the theater group Geino Yamashiro-gumi who were doing Indonesian

Kechak

dance and other ethnic dance. I was there for about a year as participating in a college club activity.

After quitting Yamashiro-gumi I started looking for some part-time job in the theater scene and happened to find a job doing odd jobs at a striptease theater in Shinjuku called Modern Art.

Even though it was a strip theater, in the 70s it was also a base for underground theater, used by underground leaders like Shuji Terayama and Show Ryuzanji. I had a longing for the atmosphere of the 70s and that was a place where it lived on and I felt good being there. It was also stimulating to me to be there.

The strip shows they did there were only topless acts where the women were trying to be artistic dancers rather than just following the trend toward more hard-core acts, and probably for that reason there weren’t many customers (laughs). So, there weren’t many strippers and there was a lot of time between acts when the stage was empty, and when I asked the owner if it would be alright for me to perform during those breaks he said OK. A rather inauspicious beginning, isn’t it. Anyway, I played a music tape and danced for about ten minutes. You might say that the strip dancers were an inspiration for me, and since it was a strip hall in name at least, I wore a sort of unisex outfit when I danced, and from the applause I got it seemed that the audience seemed had liked it. “This is great,” I thought to myself, and that was my stage debut. I was about 20 at the time, roughly in 1985. - Now that you mention this, it does seem that there is a sort of striptease theater showcase aspect to the style of your work. Could it be that that first taste of audience applause is something that you are still hooked on (laughs)?

- I guess so (laughs). Because I have a feeling that my roots are in that lower level of real-world grittiness, rather than contemporary dance or some other school of dance. In those days, up on the stage in front of a drunken audience, all I was thinking about was how to amuse them. That was really enjoyable for me.

- I believe that the dance who had the single greatest influence on who you are today is probably Anzu Furukawa. Perhaps your dance style would be very different were it not for the encounter with Furukawa. How did you meet [butoh artist] Anzu Furukawa?

- During my high school period, I happened to see a broadcast of a Sankai Juku [butoh] performance on TV and said to myself “Wow, what is this?” I also went to see performances of Dairakudakan . I guess I was developing an interest in [butoh] and just around that time there happened to be a strip dancer at our theater who was going to Furukawa’s workshops and she offered to take me along and introduce me to her. When I went, there was also a workshop being taught by Saburo Teshigawara, which I was interested in, but it turned out to be so crowded that I didn’t feel like joining in, even though I took his workshop a few times. If I had, I might have turned out to be a mini-Teshigawara and not what I am now (laughs). I learned from Anzu [Furukawa] that besides the heavy, gritty image often attached to butoh, there could also be a light, more comical aspect. I danced in her company for three years after that, until 1990.

- What was it about Anzu’s style that fitted you body as a dancer?

- How can I describe it? Her dance is passionate but it also has an aspect that lets you step back and approach the piece with a great deal of objectiveness. I think that is an aspect that I have inherited from her.

- That does indeed seem to be carried on in your works. What kinds of activities were you involved in the years after that until you founded your company in 1995?

- For four or five years I was dancing here and there as a freelance dancer, for instance going improvisational dance at small stages. I danced in the stages of Sakiko Oshima when she was about to start her company H. Art Chaos, and I made guest appearances in the modern dance performances of Takahiko Nakamura’s modern dance. When the foreign dancers that Anzu did works with when she took her company to Germany came to Japan, I worked with them. Also, I did a collaboration with a photographer and musician.

- In 1995, you founded your own company “Kim Itoh + The Glorious Future” and in the ten years since you have been a central figure not only in the genre of butoh but also in the broader contemporary dance world. What was the first work your company performed?

- We debuted with a work that took William Golding’s novel Lords of the Flies as its theme. It was around that time that I heard about the Rencontres Choregraphiques Internationales de Saint-Denis, and since some people suggested that I apply, we entered with our work Dead and Alive—Body on the Borderline in 1996.

- Dead and Alive—Body on the Borderline brought a lot of interest to focus on the Japanese dance scene. Like a few other works by artists like Akira Kasai and Kota Yamazaki, this seems to be one of the important works that broke down the boundaries between butoh and contemporary dance and achieved new strength as dance composition. The title is quite unique and I wonder if you created with a consciousness of the image of life-death questions that is strongly associated with butoh?

-

There wasn’t any specific consciousness, but I think that my words at that time had a stronger butoh aspect than my works of recent years.

Personally, I have a sense that people who live in the big urban centers are always suppressing, or killing a part of themselves. For example, you can’t look directly into the eyes of the person standing next to you on a crowded commuter train. If you were to look at them and talk to them, people would think you were weird. So you have pull down a shutter around yourself, close out the outside world and just stand there like an object. I am not a very open person myself and it is often easier to not get involved with people, so I wonder if the feeling that it is often easier not to get involved isn’t something shared by most people living in today’s urban world.

As I was dancing and thinking about this, I saw something written by Saiichi Maruya saying in essence that he didn’t know whether Japanese today are really living or not, and I agreed with what he was saying. That’s when I thought of that title. We are breathing and our hearts beat and we have bodies, but they are bodies with an existence that can be turned off. Is that truly living, or is it a form of death? Of course that kind of view of the body is not enough in itself to create a work of dance form. I had to think about the art and music, the visuals and the space, the flow of time and other things as I created the work.

Because I believe that dance is something that is composed spatially and temporally, rather than messing with the body itself I like to think about a space, where people should be in it, how they move over a given period of time and by what routes, what the speed should be, the state of the bodies, whether they are standing or what would it be like if they were sitting for a very long time those kinds of spatial and temporal aspects of composition.

In that approach the differences with contemporary dance or butoh are irrelevant. I don’t even understand the differences very well. -

What you have just said seems to tell us a lot about your style of dance. In the history of dance Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno are great figures in dance, whether seen from a Western or an Eastern perspective. The butoh dancer concentrates on the state of the body itself and that becomes the central theme, into which the dancer submerges with quiet intensity. That process gave birth to a new style of expression that had not existed before. However, at the same time, even though it is butoh, the body is still not everything. There is the space that the dancer’s body shares with the audience. In the space that is the stage, if you are given a duration of time of perhaps 30 minutes, the question becomes how you compose the space, including the body of the dancer in it. In other words, it becomes a question of how you compose the space as a whole from an objective standpoint over the course of the given passage of time. This is true not only for butoh artists but for all dance artists. Still, it seem that there are many dancers who concentrate too much on there own body and don’t give enough consideration to objective composition. In your work, besides the pursuit of bodily movement, there is also a very precise and intentional positioning of the dancers in the space and the timing of their entrances and exits, and this seems to give a high degree of intensity and substance to the composition. However, within this strong compositional element there also seems to be another direction, which might be described as a breaking down of conventional frameworks.

The work you have done in the ten years you have been working since you won the prize at the Rencontres Choregraphiques Internationales is well known in Japan, and in works like On the Map and Gekijo Yuen and Kabe no Hana, Tabi ni Deru you have used interesting devices. On the Map is a highly bold and experimental piece in which you created a multi-focus stage with cages devoted to different themes positioned around the theater and the audience uses maps they are given to walk around and view the performances. In Gekijo Yuen you used the entire theater, including the lobby and the audience seats. In these ways, prior to being dance, you seem to have unique and even tricky ways of overturning people’s everyday consciousness of the spaces they are used to. -

I’m a type who prefers events. Not in the proscenium theater but things like street events are what I like. I was a sociology major, anyway (laughs).

This may sound strange but I want to brainwash people using a variety of methods. If it were another age, I might be some country’s dictator (laughs). I believe there are a number of ways to brainwash people, such as making people read books, showing them film images, telling them stories, and in my case I brainwash by “drawing the audience into a given situation.” So, in On the Map and Kabe no Hana I blurred the boundary between the audience and the performers and reversed their positions and overturned the audience’s sense of place. You mentioned trickiness, and I guess this may be a kind of trickiness.

By the way, I got a lot of the ideas for On the Map from Anzu Furukawa’s 1989 work Rent a body-The last Night of Ballhaus performed in Berlin. In fact I think there is a considerable amount of influence from that piece in a lot of my works. Rent A Body was a work that used the entire space of a large theater hall that had a sort of two-level atrium with a gallery above overlooking the hall and a bar down below. There were 52 dancers in all, including a few Japanese and the local workshop participants. It was a two-part composition in which there was an overall scene of simultaneously occurring “happening” type dances and in the end the audience joins in dancing with the dancers in the hall. I wanted to try a similar thing with my company and that was On the Map .

I think a lot of artists are concerned about how to break loose from or break down their original fields. In particular, I think that in the field of contemporary art there is a tendency for that in itself to become the purpose. But it’s different with me. Of course there is an aspect of not being satisfied with dancing only on the stage, but with On the Map , the truth is that I just wanted to use the audience seats as a form of stage art. I thought that doing that would present a form of art that no one had ever seen before. Some people saw it also as an attempt to reverse the positions of the audience seats and the stage, but merely indulging in that kind of simple rule-breaking carries with it the danger of ending up as a limited and uninteresting device. - That kind of thinking perhaps comes from the fact that you are avoiding being limited yourself to the confined world of dance and works made only for the theater, doesn’t it? Changing the subject somewhat, it seems that a lot of the prominent contemporary Japanese dancers/choreographers of a certain generation, like Tsuyoshi Shirai and Ikuyo Kuroda , all started out in your Glorious Future company. Does this have something to do with the way you choose your members?

- At the time people become members I am not thinking about whether they have the substance to become choreographers, and I wouldn’t know that anyway. I believe the important thing is that these people already had that substance. But I should also say that in our company’s activities I always ask our members not to think of themselves as simply hired dancers but to think about what is involved in the process of creating works and to pursue their own development as dancers. As I said earlier, I’m a dictator and I do control what should be controlled, but I’m a flawed dictator and I often tell my dancers to do things freely as they wish, leaving the responsibility on them. This may sound unkind or irresponsible, but I tend to leave the details that I am not thinking about up to them to fill in, and I guess that system is working well. Former members say “Kim-san pushes you away so coldly that before you know it you have to be doing everything yourself,” and it is true that I don’t ask them to just perform things that are prepared for them but put them in a situation where they have to work out their own issues by themselves. Not only in creating works but even in daily rehearsals, I do set things up so they have to think by themselves about their bodies and their own existence. I think this must be what leads them on to their own individual artistic activities in time.

- What does the body mean to you?

-

In the end, I guess it might be a thing to play with, and commercial instrument (laughs). Because, I always think that dance begins from play. That was exactly how Anzu Furukawa thought, too. That is why I tell dancers that they should play with their bodies more, and we do that in our workshops too. I ask them to how completely they can use their bodies like toys to play with. To do that you have to take your body apart completely and use it like a completely foreign object. That’s why dancers with a narcissistic streak or dancers who become addicted to their own bodies are not interesting to me.

In workshops for example, I may do something like use a piece of cloth and wrinkle it up, stretch it out, make various shapes with it and then I say “Let’s become this cloth.” The ideal body is one with a heart that is innocent and accepting and has the ability to accept external forces naturally, but that is not an easy state to achieve. The older you get and the more experiences you accumulate, the harder it gets. - I think that a pivotal work of your career is Kinjiki that you premiered in 2005. It was a duo with Tsuyoshi Shirai and a highly intense work that seems to have so much of your work until now condensed and concentrated in it. Kinjiki is also the name of a Yukio Mishima novel and a famous work by Tatsumi Hijikata that is said to be the work that the butoh movement was born from. Other dancers would not have the nerve it seems to take such a revered name as the title for one of their works. Using this title must have required a large amount of determination and purpose, a sense of challenge, you might say. Why did you choose this as your theme?

- I may not look like it, but I’m actually quite a militant at heart (laughs). This was a worked commissioned by the Setagaya Public Theatre and at first I had put in a proposal for a rather theatrical work using seven or eight male dancers. Since this was not a company project, I wanted to do something that couldn’t be done with my company. But when I thought about it, we do works with large numbers of dancers in the company. But I also knew that I didn’t want to do a solo, so I thought about trying a duo work. And if I were going to do a duo, Tsuyoshi Shirai would have to be the other dancer. Once that was decided, I wanted to make it a work with impact, so I chose Kinjiki as the title and theme.

- So you thought of Hijikata’s Kinjiki at such a time, or was it Yukio Mishima’s novel that was the original inspiration?

- It was both.

- That is definitely rather militant (laughs). Knowing the status of Hijikata’s Kinjiki in the butoh world, most people would not think of doing a remake because of the sensation and controversy it would surely arouse.

-

I liked the movie

U-boat

about a German submarine that I saw as a middle schooler and, it may sound funny but, I had a longing for that kind of tension in a crisis. Rather than just being laid back, I hungered for a chance to do something to fuel social change, to brainwash, to instigate rebellion. So, I thought that

Kinjiki

would be a good theme to tackle.

Anyway, it became a good chance to reexamine my roots. It made me think that perhaps I really was a butoh person at heart. To tell the truth, I had been losing some of my passion for dance in the last few years, I had just turned 40 last year and I found myself looking back on the past a lot. I think part of it was that I was at a turning point. - Certainly Kinjiki is a fitting “turning point” work. How was the response to your performance at the Lyon Biennale and Düsseldorf in September?

-

The response was very good. But whenever I go abroad, whether the work is

Kinjiki

or not, I am always introduced as “Kim Itoh the butoh artist” and even more so when the work is

Kinjiki

. But it also felt a bit strange because I was hearing a number of people asking “What is butoh anyway?”

When I performed it in Japan last year I heard that there were various opinions about the work itself but I didn’t hear any talk about why I was doing Kinjiki at this point of time. So the performances in Europe made me wonder once again whether there had been any meaning to what I had done or not and how people had seen it. - We are told that after Kinjiki premiered in Japan last year you took about half a year off and went traveling around the world.

-

I really wanted to take a rest. After starting my company in 1995 I had concentrated on getting it on a productive course. But from about three years ago I had begun to feel that we were just doing repetitions of the same things and I had lost some of my creative will. I knew that wasn’t good and just as I was thinking about taking a serious rest from it all. It was a good timing that the Saison Arts Foundation introduced its sabbatical program, and I used that to take off and travel for a while.

There is a part of me that sees Kim Itoh the dancer as a second face and the other face wants to absorb a lot of different social issues and be active in a variety of other fields. Because I used to be a sociology major (laughs). In college I wanted to get involved in media but I ended up being attracted to dance due to a chance encounter, and I have been doing dance for some 20 years now. There is a part of me that is still doesn’t think it is the real me. It is not that I have regrets but more a feeling that, while the root essence of what I was searching for may be the same, the means or style of expression was different and everything came about quite by chance. These are the thoughts I was having as I was traveling. In short, as I traveled I realized what a small world I had been working in for these 20 years. I had thought that I knew the world rather well and that I had my own worldview and knowledge, but in fact I was wrong. I realized that I have been the proverbial “big fish in a little barrel.” - I think you are one of the few choreographers in the dance world who focuses his eye on society, and that may be why your travels gave you such a vivid new view of the world. Is there anything in you that you think has clearly changed now as a result?

-

Perhaps that I have become more open (laughs). I have never been inclined toward building relationships or socializing. But now I am getting out and seeing people more regularly, maintaining relationships. I can now just enjoy having a friendly cup of tea with people.

I feel that I am more willing to take the initiative to expand my fields of activity now. When I think back, I realized that this is how I was when I first began doing dance seriously. After our company came to be recognized, I guess I became a bit aloof and self-centered. I think with that six months of travel I was able to reset myself back to that more active and outgoing self I used to have. - It certainly sounds like traveling around the world and seeing other people living in conditions of poverty or living with unexpected religious backgrounds and different values has been a very meaningful experience for you. May I ask what kinds of activities you intend to pursue from here on?

-

I still have the feeling in me that I would like to get away from dance and do other things. But that doesn’t mean a complete separation from dance. I intend to maintain the valuable relationships and activities I have built up over the years, while at the same time trying new things. I haven’t yet decided in any specific terms what my relationship with dance will be, but beginning next year I am thinking of changing the style of my company. I want to take my name out of the company name and make it simply “The Glorious Future” and, while I will remain the leader of the company, I will not be creating the works but participating as a dancer in the works that other members of the company create. This autumn we will do a workshop and then we will begin activities next spring with the members chosen from the workshop. I don’t want to be making new pieces for the company myself now, but it is important to maintain a company as part of a system for continuing to perform past works, while at the same time having it be a supportive platform for nurturing the next generation of dancers and choreographers.

Also, I have a lot of interest in writing now. I am doing haiku poetry lately and writing articles for newspapers and magazines. I want to continue to develop these activities seriously. During my travels I began writing something I title “Dictionary of the Body” ( Shitai Kokugo Jiten ) in which I pick up the various expressions relating to parts of the body, like “eyes go glazed” or “stiff necked” or “quick handed” and give my own interpretation of each one in short essays. I would like to publish these, perhaps as sequels in a magazine and eventually put them together into a book. - Will you not be choreographing dance works anymore?

-

I don’t know. I may do solo improvisational dances, but at this point I really don’t want to create any choreographed works at all. And until our new company begins operating, I don’t know what will happen there. However, I am interested in the educational side, doing workshops and serving as a judge in contests and such. And, although it may be far off in the future, I would eventually like to start a school someday.

When I took this long break from dancing as a means to recover the passion for dance that I felt I was losing, in fact it ended up taking me even farther away from dance. It seems to have been a journey to shed my old self. But, I feel that this has been for the better. Rather than saying that I have lost my passion for dance itself, I feel that that passion has been shifted in a new direction that will hopefully lead to new activities from now on. Anyway, I won’t know until I begin tackling new projects.

Kim Itoh

Kim Itoh, the cross-over dancer who redefined butoh and contemporary dance in the 90s, looks to the future

Kim Itoh

Choreographer, Dancer

Kim Itoh began studies under the butoh artist Anzu Furukawa in 1987 and began solo performing in 1990. In 1995 he founded the dance company Kim Itoh + The Glorious Future. His works employ satire and a unique sense of humor in portraying “the extraordinary within the everyday.”

In 1996, his group won the Rencontres Choregraphiques Internationales de Saint-Denis for Dead and Alive—Body on the Borderline , which led to an increasing number of overseas performances. Since then Itoh and his company have presented new works at a pace of about one a year. In addition to Japan, Itoh has performed in countries including France, Germany, the UK, Spain, Argentina, the Netherlands, the U.S., Canada and Denmark.

In 2001, Itoh choreographed a work for two invited countertenors and dancers from overseas and five chamber musicians in a work titled Close the door, open your mouth (produced by the New National Theater, Tokyo) and his company also presented the new work Hageshii Niwa . For these activities Itoh received the Shuji Terayama Award in the 1st Asahi Performing Arts Awards, which is awarded to individuals or groups who demonstrate outstanding and innovative work.

Besides performances in the conventional theater space, Itoh began a new type of dance performance in public spaces called Kaidan Shugi (Stair-ism) and based on a concept of throwing the body into the everyday spaces of staircases. This series has now included performances in the seven cities of Osaka, Kochi, Kobe, Tokyo, Sasebo and Iwate.

In 2005, he served as overall director for the pre-opening parade for the Aichi World Exposition. That year he also introduced new works Kinjiki , as a duo work with Tsuyoshi Shirai, and his company’s work Mirai no Ki . From 2005 into ’06 Itoh backpacked around the world for six months. From the spring of 2007, the name of his company will be changed from Kim Itoh + The Glorious Future to just The Glorious Future and begin activities again in a new style.

Interviewer: Tatsuro Ishii

Lords of the Flies

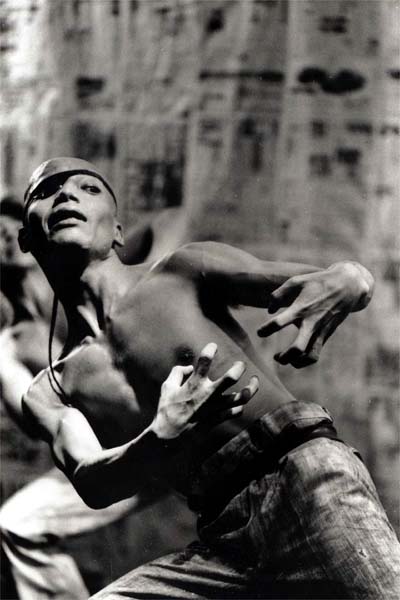

Photo: Takashi Yamanaka

Dead and Alive—Body on the Borderline

On the Map

Gekijo Yuen

Photo: Sakae Oguma (above)

Kabe no Hana, Tabi ni Deru

Photo: Miki Araki (above two)/ Koichiro Saito (bottom)

Kinjiki

Photo: Yuu kamimaki

Related Tags