The encounter with Butoh

- You studied in the Design Science department of Chiba University. Did you participate in any activities related to dance before you started university?

-

No, I never did. On the contrary, I had always been poor at sports or physical activities from the time I was a child, and in the “marathon” races they had us do in physical education, I was always the one competing with the fattest kid in the class for last place. I disliked all sports, especially ball sports. I even used to hold my ears so I wouldn’t learn the rules of baseball, all through elementary, middle and high school. Even today, I never watch the Olympics or the [football] World Cup. From a prep school in Akita Prefecture, I came to Tokyo content to go to a national university and then get a job like everyone else without really questioning that course of things. But, in my first year at university I learned that an upperclassman in the same department as me, Tsuyoshi Shirai, had just won the Rencontres Choregraphiques Internationales de Saint-Denis choreography prize. Before that, I wasn’t even aware of the existence of the small-theater world, and I had never paid money to go see a dance or theater performance. When I learned that you could go to a theater and see dance performances, I bought a copy of the entertainment information magazine Pia and when I opened its pages the first thing that caught my eye was a photograph of the whitewashed figure of [Butoh artist] Akaji Maro . So, I went to see his solo performance of the work Yukei (promise to the gods), and I immediately felt, “This is what I want to do!” So, I joined [Maro’s Butoh] company Dairakudakan.

- As I recall, Tsuyoshi Shirai’s work Living Room – Suna no Heya (room of sand) that won the Rencontres Choregraphiques Internationales de Saint-Denis choreography prize in 2000 was an excellent multimedia piece. So, you were in the same department at university as him, were you? Still, listening to your first encounter with Butoh, it sounds quite abrupt (laughs).

- I guess there was a desire somewhere in me to swing off on a completely different vector from anything I had done until then, and I believe that rushed to the surface the moment I saw Dairakudakan. Looking back, as a child I liked zombies and horror films, and I always watched the television variety programs when they had features about ghost phenomena and the like. From the last two years of elementary school into the first half of middle school, I also liked the band “X Japan” and I even copied their hairstyles using hair spray once and went to see their live concert at Tokyo Dome. In high school I was a devoted reader of the magazine Studio Voice and I ordered the photography collections of artists like Yurie Nagashima, HIROMIX, Homma Takashi and Masafumi Sanai from bookstores in Tokyo.

I believe that in Butoh I saw an aspect of those things I had been interested in, like ghosts, zombies, visual-oriented rock and other kinds of sub-culture. The first time I saw Maro-san perform, I thought that was what I wanted to become, someone dancing with a shaved head and whitewashed body. So, from the beginning it was more like doing cos-play (playing by dressing up in costumes) for me, rather than actual “dance.”- Depending on how you look at things, I can see how Butoh, with the transformation in appearance that the full-body white makeup brings, might be seen as having an element of “ cos-play .” In the case of Dairakudakan, the dancers are nearly naked with their full-body white makeup, aren’t they? Did you have any resistance to that when you started?

- No, I didn’t. Among the principles of Dairakudakan there are the words, “Even being born into this world is a great talent in itself.” So, if you feel embarrassed in your nudity, you should approach that in a positive manner and think about how you are going to act in front of the audience and show how you deal with that embarrassment—as a performer you are obliged to confront the fact that you are there to be seen, even like a freak in a “freak show.” That idea that you are an “object on view” still occupies an important place in my approach to performance.

- Does the “Pijin” of your name Pijin Neji come from the word “pidgin language” referring to the artificial language used for communication between people of different languages for trade and the like?

- I’m rather embarrassed to say that it is a name that I took on without really thinking much about it. Since long ago, there is a habit among Butoh artists of taking on stage names, and when I chose pijin it wasn’t for the meaning of pidgin language but simply because I liked the sound. Now, I rather regret that I chose a name that way.

- You were a member of Dairakudakan for a period of four years from 2000. Why did you quit after doing it for four years?

- I didn’t go to university anymore, and poured myself completely into my [Butoh] dance training. I was happy to receive pieces that people had choreographed, and I really enjoyed it. About one month after I joined the company [Dairakudakan], I went to see Kim Itoh ’s piece Dead and Alive—Body on the Borderline I was really impressed by how cool Kim-san looked, and soon I was going to all of his performances, like a fan chasing a rock star around. I loved his eye patch so much that I began to wonder why I had two good eyes, or if I could be better than him if I cut one ear off—I was really that intense in wondering what I could do. When I learned that Kim-san had quit Anzu Furukawa’s company after four years, I decided that I would also quit after four years and begin doing my own works. That’s how simplistic my thinking was at that time (laughs).

After being impressed by Kim-san’s work like that I realized that there was other interesting work out there besides what we were doing [at Dairakudakan] and I started going to see other people’s performances. At the time, there was a creative boom in contemporary dance and I felt that I wanted to join in and be a part of it [with my own works]. I had the simplistic view that if I went out there and won an award at the Toyota Choreography Awards or the Yokohama Dance Collection it would be my ticket to making it into that world.- You now have the ability to win attention as a choreographer, but you also possess elements of both Butoh and contemporary dance that make you a unique presence as a performer. You performed in the production ASOBU directed by Josef Nadj that won so much attention at the 2006 Avignon Festival, and you have done collaborative work with artists both in Japan and abroad. Earlier you said that Butoh had a “cos-play” aspect that attracted you, and I find that an interesting perspective on Butoh from the young generation. You are the first one I have ever heard calling the unique makeup of Butoh “cos-play” (laughs). Would you tell us in a little more detail about this relationship between cos-play and Butoh?

- An easy way to explain it might be by telling about the workshop I did two years ago at the Akita Public University of Art. It was a job I was given under a request for a Butoh workshop, but I wanted to do something a little different from just the usual Butoh exercises.

First of all, at the beginning of the workshop I brought out a lot of photos of Butoh dancers I had found on the Internet and printed out, then I got all the workshop participants to tape them up all over a wall. Next I got out photographs of the well-known “ ganguro girls ” men of Shibuya (who tan themselves a dark tan at tanning salons and dress up in costumes like the ganguro (dark tan) high school girls), the cos-play girls in Akihabara who dress up like anime characters, host club men, visual-oriented rock band members, motorcycle gang members, drag queens, etc., and had everyone tape these photos on the same wall intermixed with the Butoh dancers. And when we did, it is undeniable that the Butoh dancers looked no different from these other people who create their identity with the costumes they wear—in other words “cos players.”Among all of these photographs, the ones that generated the most energy were the famous “Hat Man” of Yokohama and [Butoh artist] Kazuo Ono. When looked at in this way, what Kazuo Ono was doing indeed looked like true-blooded “cos-play.” Then I began my talk, and I told the students that when I started Butoh it wasn’t to do dance but because I wanted to be connected to that kind of energy.Then I told them, “Let’s all try doing some cos-play now.” But, when people are suddenly told something like that, there is no way they are going to just jump into it. I took out a oil Magic Marker and asked one of the participants if I could write the character for “muscle” on his forehead [like the anime character “Muscle Man” ( Kinniku-man ), and he said, “No.” In other words, there are always a certain hurdles that you have to overcome in the process of beginning cos-play. It may be because people are worried about what others will think, or because they are simply embarrassed to do it. So, we then look at where that hurdle lies. Then we begin with the lowest hurdles and soon people say, “Well, maybe I could do that,” and you begin clearing them one by one until the process starts to escalate and you get to a point where you should be able to do cos-play. And as this is happening, the resistance inside your body begins to melt, and that is where I said, “OK, let’s begin some dance training.After that process of breaking down resistance with that, “Well, maybe I could do that,” attitude, the participants’ willingness to try things escalated. I had brought along the sets of materials for doing the Butoh body whitewash and the Butoh loincloths—that we call tsunpa (phonetically the reverse of “[under]pants” in Japanese)—and some props I had picked out at a nearby 100 yen shop (dollar shop). Using these, we soon had one housewife of the kind who might have done ballet when she was young take these materials and wrap her whole body in Saran Wrap, put a plumbing drain net on her head and hang little bells from her ears and begin walking around shaking her head with tinkling bell sounds. Meanwhile, a civil servant from city hall had put a colored cone on his head, and before I knew it, another man had whitewashed his whole body and put on the loincloth and stuck a plastic flower on his face and began dancing.- There certainly is a tendency in which changing your external appearance in what until then was unthinkable ways can also cause dramatic changes in a person’s [inner] feelings as well, isn’t there? Simply starting this cos-play had obviously sparked a change in them, had it?

- Yes, it had. It looks very Butoh-like. The one that had the biggest impact on me was a man of about 20 years of age. He was acting very noncommittal. He wanted to try wearing the Butoh loincloth ( fundoshi ) but he said he felt embarrassed because had a lot of dark hair on his lower body, so I told him that if he went off somewhere and changed into it and then came out wearing it, no one would care about the hair. So, he went off to the restroom and changed into the loincloth and then started applying the whitewash makeup all over his body. Then he decorated his body with plastic flowers and scrub brushes and was nearly out of breath when he finished.

After doing this cos-play workshop, we all went out onto the campus beating African drums and naturally started dancing and interacting actively with the students that we met along the way. There was a great feeling of exhilaration in all the participants, like at a festival. Then we ended by making a full-speed dash together back to the workshop hall, and as we ran the things (props) they had decorated their bodies with were falling off on the ground here and there. Then, as we were resting after the dash, we could here the tinkling sound of the mother who had hung bells on her ears coming back slowly in the distance so the bells wouldn’t fall off. The sight of her was so delightfully comical. I never thought the workshop would get everyone as excited as it did. It was a very meaningful and rewarding workshop for me.- You are performing while perceiving the interaction between yourself and the people around you—that interplay. There is a kind of excitement or elation in that. Is that the same as your physical state when you are performing on stage?

- Yes. That is the physical state I want to be in, and I believe that is the kind of dance I have been doing. In other words, by loosening the inner depths of my body, I am able to put myself in a state of relaxation and move while communicating with the environment around me, including the stage and the audience, or choreograph a system of that communication with the surrounding environment and execute it [as performance]. This physical state of being is something that I feel I can pass on to others as my method.

A performer is expected to control his or her body on the stage, but when you expose yourself to view in front of an audience, there is no way that it is not going to affect your body. You are being looked at; you are going to be nervous. The fact that this makes your body unstable is one of the elements that is always present in dance. It was already at too late an age when I first began to learn dance technique, and I believe that the reason I arrived at this form of focusing on communication with the surrounding environment was the result of my attempts to find what assets I had at my disposal and what methods I could use to stand on par with other forms of dance. Now I feel that this is my pointe .

The period of experimentation and thought

- Are there any artists outside the genre of Butoh that have influenced your performance and choreography?

-

Chelfitsch’s

Toshiki Okada

is one. Okada is a theater artist, but when I saw his work

Cooler

that won the 2005 Toyota Choreography Award, I was really shocked and impressed to see someone from outside the dance context bring such amazing physical expression to a work. Clearly it is actors that he is directing and they are speaking lines and their movement is not something that could be called “dance” in conventional terms. Nonetheless, my body told me that what I was seeing was nothing other than dance. Watching it, I couldn’t keep my body from twitching in response to what I was seeing. Until then, I had thought that my creative activities in dance would be an extension of the efforts I made to train my body and acquire technique. Now I know that there are indeed special skills/technique that are required of chelfitsch actors, but at the time I first saw them the shock of what I was seeing completely overturned the fundamental ideas I had about dance and physicality. The night after I saw that performance of Cooler , I ran a high fever. And, because of that trauma, I was too afraid to go to another chelfitsch performance.However, that experience led me to do a lot of research about Okada-san and I found that Natsuko Tezuka had apparently had a significant influence on him. So, I applied to attend one of her workshops and it turned out that at the time I was the only applicant. The result was that it turned out to be a one-on-one workshop, and that was a wonderful experience.

- Toshiki Okada’s Cooler was a work with fresh originality that could certainly have won the Grand Prix, and I believe the only reason it didn’t was because it was seen as theater rather than dance. And, when you cook at chelfitsch’s international accomplishments and reputation after that, I feel they have gotten the rewards they deserve. In Tsuyoshi Shirai and with Toshiki Okada, you have gained valuable experiences in the leading developments of contemporary Japanese theater. As for Tezuka-san, she is an artist who gives very compelling performances by a technique of filling various parts her body like her fingertips and face with palpable tension. She is one who is able to attain a high level of [positive] tension by focusing energy inside the body. What were her workshops like?

- Tezuka san is an artist who actively pursues the process of putting the things she does [in performance] into words. Seeing this, I realized that I had been plunging headlong into the things that interested me without really thinking about what they actually meant to me. In the process of going through a number of physical experiments with her, I began to see clearly what those things meant to me.

For example, you touch one point on your body and focus hard on it with all of your consciousness. When you focus all of your attention on one point of the body like that, the other parts of your body are no longer under the control of your consciousness and thus begin to move by themselves. When you focus your attention on a point behind your wisdom teeth [for example] the other parts of your body begin to move by themselves. Also, Tezuka-san told me to draw pictures of the body, telling me for example to focus my attention on parts of the body that you can’t see, like the inner organs, and then she told me to concentrate and get an image of my stomach and then actually draw that image.In other words, Tezuka-san’s dance involves a process of observing the internal parts of the body, and by doing so enters a state where if something external influences or affects the body, the body will move in response to it—you don’t move intentionally, you “tune your body” so that it is moved by those external influences. And, in that aspect, I thought it was similar to the concepts of Dairakudakan Butoh.At Dairakudakan I was often told not to move [intentionally] but to be moved. It is a state of dancing defensively rather than offensively. For example, in the case of walking in the suri-ashi style (walking without lifting the feet but by sliding them along the floor), you don’t think of “walking” [by moving your feet deliberately] but having your body move forward by means of a movement of its center of gravity. In the same sense, you don’t “jump” upward but are lifted upward as a suspended body [as if hanging from a cable]. Although these are simply changes in wording, they definitely produce a different kind of physicality. However, because I had never observed the inner body as carefully as Tezuka-san, I found something very fresh and enlightening in her method.- Are you saying that through Tezuka’s workshops you found a new form to physicality as a performer and that it showed a method that you now use on stage?

- Yes. From 2007 to about 2009, I did workshops and participated in a project called Dojo-Yaburi that gathered dancers to exchange methods and did performances together with them under the name “ Jikken (experiment) Unit,” and in the process of that, I believe that my interest shifted away from dance toward physicality.

One time, Tezuka-san said, “Cos-play is an act of deviating from standard norms to come in contact with excess, or the extreme,” and she cited the cos-players in Akihabara who dress up as anime characters and the ganguro (deeply tanned) people you see around town as examples. Those words really struck a cord in me.After that, when I looked at pictures of these kinds of cos-players and the zombies and visual-oriented bands I liked as a child and looked at them together with photographs of Butoh dancers, I felt the same kind of energy in them all. It is all very cos-play in nature. In other words, it was then that I realized for the first time that it had been my encounter with this kind of extreme energy that had started me dancing. When I was a member of Dairakudakan back then, taking something like eye-lining, it would have such a powerful impact for me when I made myself up like that, that it actually had a big effect on my body (physicality). And, although they might have looked strange from the outside, they were all things that I chose because I felt I could be honest with myself when I did them. Today, however, I can’t make myself up in that Butoh style anymore. I won’t be using that style with whitewash on a naked body anymore.- After having gone through your Butoh period, you became active in a cross-over style that wasn’t Butoh and wasn’t contemporary dance, but could also be seen as both, and now, looking back, what are your feelings about the Butoh that was the roots of your performance career?

- I believe that I am of a generation that is no longer connected to the people who started Butoh. When I came in contact with Butoh it was already mature (complete) as an art. If that wasn’t true then I wouldn’t be able to look at it as a form of cos-play. So, I always say that I have not “inherited” Butoh, but rather I “recycle” it or “reuse” it. Rather than saying that I am part of the Butoh genre, I feel that I am a performer who has recycled Butoh from a stance that is separate from that tradition.

For example, my technique is a reuse of what I learned at Dairakudakan, and I also use many of the physical elements of it. When I look at the old films of Tatsumi Hijikata performing, there were numerous elements, like the very unstable look he had when performing on wooden geta sandals, or the way his heavy headpieces made him hold his head to the side and the way his white was made his skin twitch, that make me feel that, besides the symbolic elements of his appearance, there are many things that show how serious he was about experimenting to invent new forms of physicality.Listening to tape recordings of Hijikata speaking, since I am also from Akita Prefecture, I realize that Hijikata’s Akita dialect isn’t a true Akita dialect. What I mean is, his Akita accent is one of a person who had lost his accent once and then tried to revive it. It is the same as the accent I have when I go back to Akita and try to speak with an Akita accent again. In other words, Hijikata had once separated himself from Akita and as he was doing modern dance [in Tokyo] he was thinking hard about how he could develop a sustainable form of dance for himself. And, I believe that in the course of that quest he deliberately reuse elements of his native land, the northeastern Tohoku region of Japan to create the new dance form that would become Butoh. In that sense, I think you can say that Hijikata was “recycling” Tohoku.- I am also curious to ask what kind of experience it was participating in Josef Nadj’s production ASOBU .

- Although I had already left Dairakudakan at the time, I participated in it as one of the Dairakudakan dancers. We weren’t given choreographed parts but had to create our own parts, so I remember it as being quite difficult. For two years, beginning in 2006 I was going back and forth to France to perform in Nadj’s works, and I did have a choice of remaining in France to work as a dancer, but I decide to leave France in January of 2007 to return to Japan with hopes of creating my own works, even if it meant that I would have to take a side job to support myself in the meantime.

As a choreographer

- I am very interested in your activities as a choreographer. Your work “syzygy” that premiered in 2009 involved a large plywood board, four pillars and two dancers, whose bodies were used in the same way as the board and pillars, dragging the board and rolling the pillars around the stage with a with strong, almost violent movement of the bodies and objects alike. This work of yours won the Jury Prize, the Grand Prix of the Yokohama Dance Collection EX 2011. It was a work that focused entirely on the material elements and the action, devoid of any emotive or narrative elements, wasn’t it?

-

It was a work that I created with support from Asahi Art Square’s “glow up! Dance project.” It evolved from ideas I got while thinking about whether or not I could do something using the plywood board that happened to be lying around in the venue. I took the title from a novel by Theodore Sturgeon that I liked. It has two meanings, one of the time when two planets align and the other meaning a card trick where you have two cards face down one on top of the other and turn over only the upper card. At the time I was influenced by New York’s post-modern dance movement and I found the results interesting when I tried using the bodies of the two dancers, Megumi Kamimura and Mari Fukutome, as inorganic material. After the initial shock of seeing chelfitsch works, I believe that I wanted to separate myself from the very organic physicality of Dairakudakan and do something completely opposite.

- After that, in 2010, you presented the work “The Acting Motivation.” This was a work in which you appeared along with artist Minoru Ide a friend of yours named Wada from the convenience store where you worked part-time to support yourself. It was in the form of a semi-documentary composed of a mix of real images from the lives of artists who have to work to make a living and fictional images. I saw it at the 2011 Festival/Tokyo (F/T) and I found it to be a wonderful work in which the premise was that it was a fictional stage work but also had elements linking to the real outside world. I have never seen a Japanese contemporary dance artist create such a work and I believe none could. It was completely different from the inorganic nature of “syzygy” and with it you surprised me with the breadth of perspective in your creative capability.

- Most of the artists living in Japan have to work at part-time jobs to support themselves, and it is really difficult to continue creative activities while working to earn a living. At the time I was working at a convenience store and I was really concerned about my identity. Was I freelance part-timer doing dance as a hobby, or was I an artist who worked part-time to support himself! This work has been restaged a number of times, but when I created I was really in an extreme state of mind with worries about my future, and then in the meantime there was the 3.11 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami.

The original impetus for this work came when I was asked to create something for the fringe project for the Kyoto Experiment. I accepted but I didn’t have the time to train and rehearse in the studio or to think about what kind of piece to do. It was such a painful position to be in that I began to wonder if I could look at my part-time job as a form of studio training. For a month and a half I worked eight hours a day at one convenience store and another six hours at a different store, so I was working 14 hours a day.As I worked, I did things like counting how many times a day I repeated the standard greeting when a customer entered of, “ Irasshaimase, konnichiwa ” (Welcome, good day), calculating in terms of calories how much I was working compared to dance, what differences there were in the effect on the state of my body when different kinds of customers came in, did my center of gravity shift to the right or to the left, and things like observing the feelings I had in my internal organs. That is how I worked it up into a piece for performance.For the premiere, it was performed by myself, my artist friend Ide and one of my colleagues at the convenience store that seemed to have the least interest in my dance activities, and for the performance at F/T I got the Bungaku-za company member Kaoru Soya to take the place of Ide and also changed the composition some. Looking back on it, I feel it was something like the blues. Like the way the black slaves took the instruments of their white masters and created their own different kind of music using them. So, you might say it was a kind of blues that someone living in Tokyo who didn’t know if he was an artist or a freelance part-timer created by watching and copying the documentary theater style of Europe (laughs).- This work won the Best Work award of the F/T open selection program. As a part of that award you were also given the right to create a work to perform at the next year’s F/T, but I heard that you turned it down. It was complete with a generous budget for production and the opportunity to premiere a new work at a high-profile international festival, the kind of opportunity that most artists would jump at, but you turned it down. That may be one of the best things about you (laughs), but why did you turn it down?

- After the performances of The Acting Motivation , I had the feeling that I wouldn’t be able to find anything more that I would be interested in doing, and I was even thinking about quitting my activities as an artist. I had reached the point where I was feeling that I would be deceiving audiences if I continued to present works like The Acting Motivation as theater. But, I had been invited to perform it at the Festival Bo:m in Seoul in April of 2012, and I had decided to do this one last performance. It so happened that there were many stores of the same convenience store chain that I used in this work there in Seoul and that in South Korea there are also many artists working at part-time jobs to support themselves. But, that was the last time that work was staged.

- But it was good that you were able to restage it in Seoul. After that, it seems that you had many opportunities to dance as a guest performer in different places.

- In February of 2012 I had the opportunity to appear as a guest dancer in the faifai production Anton, Neko, Kuri , and for the first time in quite a while I was able experience the joy of dancing. The work then toured overseas and it made me realize anew how very important dancing was to me. For about two years after that I continued to participate as a performer in a variety of artists’ stages, which was a great joy for me. It made me recall the days when I was dancing for Dairakudakan. Being able to perform a part that someone has choreographed for me is one of the greatest joys I know of in my life.

Also, just around that time the experience of performing in Tezuka-san’s work “ Shiteki Kaibou Jikken – 6” inspired me with the idea that the body is a form of media.- What does that mean?

- This work was based on the concept of the “dividual” as opposed to the “individual” (a concept proposed by French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, meaning a communal entity as opposed to an individual) and in the creative process of this work I was made to become conscious of the individual’s body and the communal body. Tezuka-san had an interested in the “dividual body” that served in communal context where the boundaries between other individuals are loosened, but in the course of performing in this piece I found that, from the bottom of my being, my orientation was unmistakably opposed to the dividual. Although I have some attraction to forms of expression like the Bon Odori festival dances [where everyone dances the same step in unison], I am one that essentially needs a certain amount of distance between myself and others.

However, I am also influenced by the society and the environment that I live in, and this bond with society is something that cannot be severed. My “individual body” is in fact full of many societal elements, and I feel that by showing my body I can communicate fragments of the things that are occurring in society. When I thought that, I became aware once again of “the body as media.” If that is true, then I felt that I wanted to use this body to create works, and for the first time in two years I created a new work, which was “Air or Fart” that I performed in 2014.- In that work, the sight of you moving in response to the movements of a white curtain left a strong impression on me, but I also felt that it was work with which you were searching for the next step in your creative activities; a sort of transitional point.

- After the 3.11 disaster [Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami], I thought that even after everything was swept away like that, someone would surely begin making dance and songs again spontaneously on their own. And that would be something as natural as air, or a fart. So, this work “Air or Fart” was an attempt to see if I could capture that idea and express it in a work. Perhaps it wasn’t the kind of work that I should be presenting audiences with, but I felt that that kind of honesty to a fault was something I needed.

- When you are creating a work, is there any particular methodology that you use?

- I make a point of conducting extensive interviews. I am curious to know what a particular person knows, what they are concerned about, what this person is made of. Rather than gathering at the studio to create a work, I believe it is more important to get the people who will participate to come together and report to everyone what is happening in their lives, what their present situation is. It is the things that catch my attention during those talks, or things that raise doubts in me, things like shared experiences when people go someplace; these things that I have receive in my “body as media,” as a medium, become the important elements in a work, I believe.

- How do you reflect the contents of these interviews in your works?

- In some cases they will influence the composition of the work, and sometimes I will use the contents as they are for [parts of] a performance. In the work “ Solysomundopsy ” (Meaning “no sound or even gossip” in direct translation. A word that is used in cases such as a purge where someone disappears and is not heard from.), which I performed in Busan (Pusan, S. Korea) in 2014, we did interviews of people on the streets in Fukuoka (Japan) and Busan about the current gossip or rumors going around in each city.

This work was created as part of the “Plan Co” program for collaborative works between Japanese and Korean artists, supported by JCDN and the Fukuoka City Foundation for Arts and Culture Promotion on the Japan side and the Busan Cultural Foundation and the LIG Arts Foundation on the Korean side. The period allotted for creation was just two weeks, meaning there wasn’t enough time to create a dance work, so I decided to take the interview material that had been gathered and edit it using what struck me as interesting to turn it into a performance. I wanted to create a work with children, and when they gathered teenage participants for us in Busan, by chance it turned out to be middle and high school girls from a school for orphans. Usually, when you ask someone about their name you will ask who gave you the name or who did you inherit this part (character) of your name from, which will tell you about their lineage, but in the case of these orphans they don’t know that information.When you think about it, no one really knows where a rumor comes from or where a folk art comes from. It may be that something that was originally created in an impromptu way evolved over time to become the folk art we find today. While thinking about things like that, I edited a variety of elements related to Japanese and Koreans and Fukuoka and Busan to create a performance.- Hearing this, we begin to understand about the meaning of interviews and editing in your creative process. I believe this is an important process when considering how to pick up and reflect the diversity of people living in today’s society. And, I think there are not many creators who work that way.

About collaboration

- You have been producing good results in collaborative work with people from different genres and countries. For example, recently you have created a work with the choreographer Jeeae Lim, who worked for a long time in traditional Korean dance and now lives in Berlin and is active in contemporary dance. This work you did with Lim involved three dancers and what impressed me especially about it was the way your physicality with its unique Butoh flavor stood out as different from the others. Watching it as a member of the audience renewed my awareness of the power of Butoh.

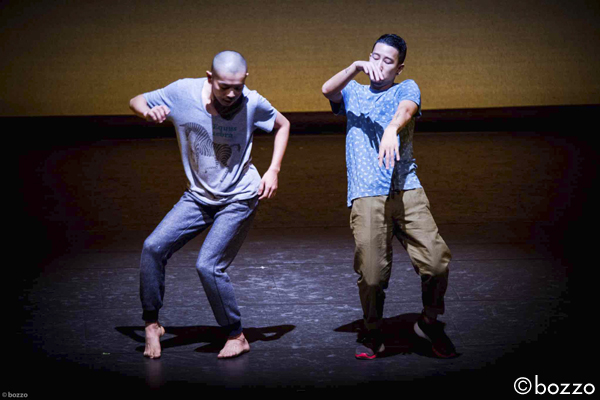

- The work Ten Years in 1 Minute presented at Festival/Tokyo (F/T) last year (2014) was one that resulted form a collaboration in Busan between myself, Lim and the Romanian dancer Sergiu Matis. The work no title is one that I performed at last year’s Toyota Choreography Award 2014 together with the house dancer Yanchi. Until then, I had thought of my technique as something little more than acquired habit, but while working with other dancers who have technique of their own, I came to think of my body itself as one form of technique, and I realized that I can dig into it and compare it with the technique of others.

- Lately you have also been doing a number of collaborations with the contemporary artist Tetsuya Umeda. I have seen a work that Umeda-san did with contact Gonzo at the Aichi Triennale 2010. You and Umeda are from the completely different genres of visual art and dance. But in the world of creation, you have styles that are bold and free of personal obsessions and you seem to have things in common in terms of live action and your consciousness of spaces. I feel something very similar between you and Umeda.

-

I have received a lot of inspiration and stimulation from Umeda-san. I first met him at the opening event “

Teiden

(blackout) EXPO” of the International Festival for Arts and Media Yokohama in 2009. It was a performance produced by Yasuo Ozawa of the Japan Performance/Art Institute and brought together contact Gonzo, Megumi Kamimura, Tetsuya Umeda and Kanta Horio. Having met him there, I went to see one of Umeda’s live performances in Harajuku. His live performances start out simply but before long the audience becomes involved and things develop into a state approaching chaos. I didn’t understand what caused it but it naturally draws people into it. It really surprised me and had me asking, “What is this?” When I talked to him I learned that by chance we were both born in 1980. When I see Umeda’s work I realize that he has a natural freedom that lets him easily cross boundaries and things that most of us are concerned with, and I thought that ability was really cool.The way he is able to move people, the way he makes spaces move, there is an unexpected strategy by which he knows how to make something move, and in a broad sense I thought that this methodology of his can be seen in a way as a form of choreography. That is what interests me. Right now, I would say that there is no one else’s work in the world that I like more than Umeda’s. I find that everything he does is OK with me.

- I definitely hope you will do more collaborations with Umeda-san. Finally, I would like to ask you what you are planning or thinking about for the future.

- Recently, I went to HAU in Germany, and I felt that the theater was functioning successfully as a media. I had the same feeling when I performed at Kobe’s DANCE BOX, and now I have a strong desire to create works to perform at theaters like that that function as media.

If the body, the stage format and the theater as a place all function as media, I feel that we can experience the condition of being honest with ourselves to a fault as we perform and we can communicate something to the audience about the kind of world we are living in today. Rather than keeping things inside ourselves, I want to be active with a consciousness that I am involved in that kind of media.

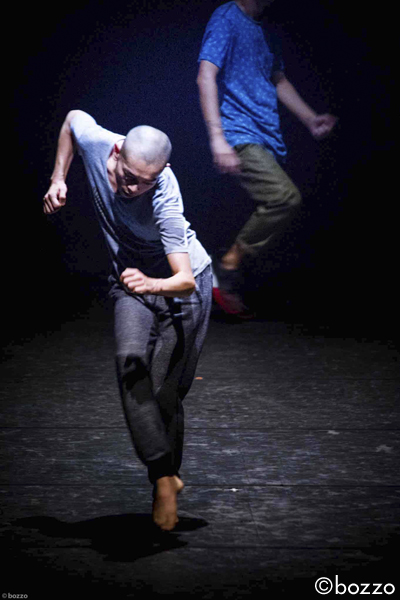

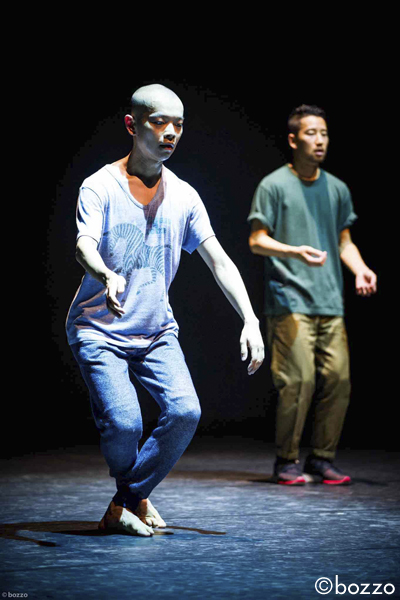

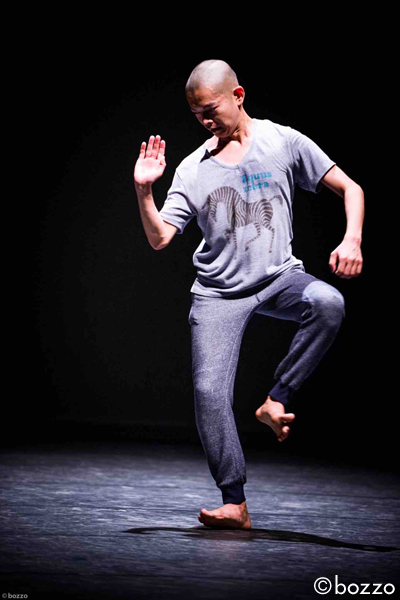

no title

(2014年)

Photo: bozzo

syzygy

Photo: Kazuyuki Matsumoto

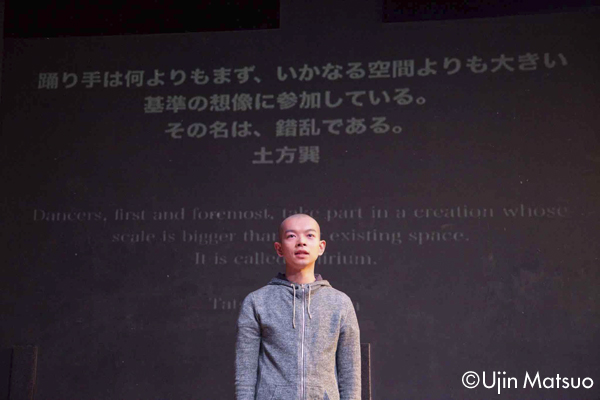

The Acting Motivation

Photo: Ujin Matsuo

Air or Fart

Photo: Yoichi Tsukada

Ten Years in 1 Minute

Photo: Kazuyuki Matsumoto

no title

Photo: bozzo

Related Tags