- Congratulations on winning the Kishida Drama Award! Since your 2008 play Kazoku no Shozo (Family Portrait) , your works have been nominated as finalists for the Award three consecutive years with high acclaim for their contemporariness. Would you begin by telling us about the award-winning play this time, Jiman no Musuko (My son, my pride)?

- Jiman no Musuko is something like a sequel to Kazoku no Shozo (Family Portrait). What I tried to do with Kazoku no Shozo was to intentionally put together in one place and one time a group of solitary, lonely people—a reclusive son and his mother, a part-timer, a convenience store clerk—and portray them as layered entities. And I placed the audience on all four sides in a raised position so they are looking down on the stage as if looking into a pool. The play itself was still in a state of experimentation, but I got a definite feeling that this kind of special orientation worked well with the text.

As in Kazoku no Shozo, a relationship between a mother and son is central to the story, and I wanted to make it a play that involved the parent and child fighting over control of certain spaces in order to stake out their own individual territory. Then, building on that, I wanted to introduce outsiders coming in to the parent and child’s space and portray the process of them pushing and pulling each other out of those spaces.

In this case “staking out one’s own territory” becomes an act of “expanding the realm of one’s own story.” People try to measure others by their own standards and only see the aspects of other that they are able to measure. In that way they label each other. In other words, people only want to see each other in terms of their own personal stories. And, I think that is true with parents and their children, too. From the moment parents give their child a name, they are labeling the child with a sort of story, and the children themselves come to believe that they have to do their part to live out the story their parents envision. Of course, there are times when they rebel and say, “This isn’t my story,” and there are also times when, conversely, they try to envelope their parents in a different story. Seen in this way, even the naming of a child can become an extremely violent act against an individual. I wrote Jiman no Musuko as an attempt to explore the possibility of making this idea the basis for a story. - Among your plays are Tsuka (Passage) that depicts a household ruled by the bedside bell rung constantly by the family’s bedridden grandmother who is never seen and Calorie no Shohi (Burning up Calories) based on the old stories of poor villagers abandoning their elderly in the mountains and others besides these two works that deal again and again with the theme of relationships between parents and children, it appears to me.

- That is definitely a fact [laughs]. It is a theme that I like a lot, I guess. Stories about relationships between parents and children make it easy to depict twists in the storyline. Even though they just happen to be parents and children, it is easy to superimpose a story about a “fated bond” on that relationship, isn’t it? However, the fact that it is easy to see blood bonds as fate also makes it easy for discrepancies or variance to occur, I believe. When a story is created based on an exaggeration of the importance of heredity and blood relations, dramatic developments of betrayal and love-and-hate relationships that wouldn’t occur between strangers can become tragedies within a parent-child relationship.

I myself was a child who grew up depending on my grandmother, I think I have had a tendency to rebel against stories that bring in a grandmother instead of the mother. The more they surround you with love, the stronger the sense that you can’t escape from that relationship. Furthermore, the older a person gets the hard it is for them to physically continue the stories they have created in their lives, so even if they say, “I will protect you,” they lack the physical strength to do so. Although a reality gap has begun to emerge between the self in the story they have create and the physical self, they try to envelope people in their story.

I have this image of children trying to become independent from parents who are trying to protect them. The image is one of a mother breastfeeding the baby while the baby gets an erection, inserts its penis in the mother’s womb and ejaculates. The son is being protected by the mother but at the same time he is strangely independent; the mother thinks she is protecting the son but the son, in his independence, has chosen the mother as his partner for implanting a new life in her. This repulsive kind of dependency that can neither be called protection or independence exists, I believe, within what is called “independence” in Japanese society. As I am writing my plays, I am thinking, can’t this be called “independence,” or, isn’t it a question of “letting go of the child”? - “Fate” or “reality gaps” are often the stuff of tragedies. I your case, however, I feel that you even look down on such themes and seem to be espouse a mood that approaches the mythological. In Jiman no Musuko you placed a blanket on the floor and had its movements or disarray symbolize changes in the “territories” occupied by the characters. In the final scene you used the devise of having a remote-control helicopter circle over the blanket to what seemed to me to be the effect of turning the world of the stage itself into a spectator.

- The helicopter was the idea of the stage art staff, but I am glad to hear that it gave you that impression. We may tend to think in abstract terms such as “buffeted by the winds of fate” but, in actuality, the actor on the stage is more often affected and moved by “spaces” or specific “objects” or “people.” That is the feeling I like. For example, saying that a desk is a boat or that the tatami mats look like a desert and have those images affect the actors’ positions or postures. Simply flying a remote-control helicopter around the stage creates a new perspective—even though the size of the actors or the stage doesn’t change, you can create a new sense of scale for the audience. Even if it is only in certain places, I want to create that sense of “being moved” by something.

- On your Sample website we find statements like, “In other words, we do not act on the basis of choices that we have made actively but, rather, we are passively made to select things and then act on the basis of those choices. We are creating stage works that take that assumption as the basis for acting.” When you are writing your plays are you thinking about creating those types of situations?

- The actual working process begins with taking the subject I want to portray and discussing it in meetings with the stage art staff, the dramaturge and the costume, lighting and production staff people. I only begin to do the actual writing after we have discussed how we are going to give expression to that subject in a specific theater space down to details such as where the audience seating will be positioned. Then I write about one third of the script before we enter into studio work-up stage. The remaining two-thirds are composed through in response to the specific needs that arise. For example, if an actor says that it is difficult to move the cloth in this situation, I will write lines that make it easier to move it, or if the art team wants to fly a helicopter, I will create a scene for that.

- You mean the play script doesn’t come first?

- That’s right. I began to experiment with this working method from Calorie no Shohi (Burning up Calories), then with Kazoku no Shozo it began to take shape and finally reached a certain degree of completion with Jiman no Musuko, I believe. In the past I used to pass out copies of a completed play script to everyone and tell them this is how I wanted it to be done. But, that led me to feel that I had to try to get beyond the things I could create just within myself; I realized that there was a limit to the variations on ideas that I could conceive all by myself. Now I find taking ideas that emerge when we are talking freely and then trying to make them work on the stage is what really stimulates me.

In this process, the presence of the dramaturge Masashi Nomura is very important. He officially began participating in the creative process from Kazoku no Shozo. The presence of someone like him who to speak across the boundaries of theater specialties like stage art and costumes has made it easier for other people working on the productions to voice their ideas more freely. His is a mysterious presence. He is not like many highly academic dramaturges and he is not like a producer either. When I tell him the kind of thing I am thinking of doing he brings a bunch of materials that help broaden the scope of ideas. Having a person like him involved makes the creative scene much more interesting.

I think that the kind of top-down operating situation where you have a writer-director dictating everything can’t produce things with realism anymore. When you look at information sources today, it is no longer just television and newspapers anymore, because now the social media like Twitter are another important source. So, everyone has their own ways of getting information. It becomes a question of how you deal with that. If people making theater don’t change with the times they will lose their reality in the eyes of the audience, I feel. - Tsuka (Passage) is a family drama, while Chikashitsu (The Basement) was set in the shop of a cultish natural foods business. Unlike these earlier works that had settings based in the real world, your works since Calorie no Shohi (Burning up Calories) seem more ambiguous in terms of when and where they are set and in their visual aspects they seem to be increasingly abstract.

- There has definitely been a change. I am roughly of the same generation as Toshiki Okada of chelfitsch and Daisuke Miura of potudo-ru, and the presence of artists like them was naturally a big shock for me. So, at first you might say I was fluctuating between Miura’s kind if intense realism and Okada’s attempt to blend dance and realism and the sense of Neo Romance it produced. To some degree I was being swept along by both of their influences. You can see that in the strong influence of Miura in my Chikashitsu (The Basement). However, from around the time of Calorie no Shohi I had become independent from Seinendan and had established a “theater company” of my own, and I feel that was giving me a direction of my own.

- Sample was originally a company made up of young Seinendan members who were participating in its performance series for young creators. Would you tell us about how Sample came to be formed?

- At Seinendan there was a performance category where young members could present their own works under a system that involved submitting a plan and a budget to the company and, if you could get together enough company members who wanted to take part in the production, the company would give you a grant and use of one of the company’s theater spaces (Komaba Agora Theater, Atelier Shumpusha). From there, members could form “Seinendan Link” groups and those who wanted to become independent could do so. Basically, the philosophy of [Seinendan leader] Oriza Hirata was that people in the directing department should eventually go independent. So, when I got an offer from an outside theater (Mitaka City Arts Center) to mount a production, that became the opportunity for me to go independent.

Our company name “Sample” was chosen because I wanted a name that wouldn’t give any sense of independent direction or intent. Rather than what you would call human dramas, I wanted to do works that looked at the world from a bit more detached and objective viewpoint. As if I am working with samples or elements of an experiment, my works are the result of a creative process similar to scientific experimentation—watching to see what kind of chemical reaction will occur if I mix a particular set of raw materials. It may be a mix of people and things, or it may be a mix of space and human beings. In either case, there is an aspect of seeing everything as raw materials, or “samples.” - After graduating from university you entered Seinindan as an actor. What motivated you to begin writing plays?

- From the time I was a university student, performing as an actor was, naturally, something I did because I had the desire to express myself and my worldview as best I could. After entering Seinendan, I went along with Oriza-san to his play writing workshops and faithfully took notes about how to write plays. But, no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t write well. That continued for about eight years. I believe that during that period I was searching for my own subject, but it wasn’t something that could be found right away. Then, one day I decided to try writing something that began from daily conversation, like, “Hello,” “Oh, hello.” But, in between the lines I begin to add acts that aren’t every day. By doing that, it begins to reveal the relationships hidden between the lines of everyday conversation. The fascination with this process is what kept me writing. And when I was writing in this way, I tried as much as possible to write in the directions of lowest probability, the directions that are hard to imagine. That is because writing that way provides a greater possibility of unexpected things revealing themselves. This has become my writing method for plays.

- One of the first products of that writing method was your maiden work Tsuka (Passage) that was nominated as a finalist for the Japan Playwrights Association’s New Playwright Award. In this play about a submissive couple whose life is being dominated by the bedridden mother they are caring for, an older brother who preaches about building a Utopian world comes into their lives and begins to reveal the desires and anxieties and dependency relationships existing beneath the surface of what had supposedly been their peaceful life. In the process, some unusual and abnormal sexual aspects are revealed as well. These qualities seem to be consistent in all of the works you have written until now.

- In Tsuka I wanted to explore the process of an outsider come into the life of a couple and begin to turn it upside-down. What life decisions do they make when confronted with this situation? I was interested in seeing them make the benevolent choice of accepting the outsider and then be trampled on as a result. Therefore, it wasn’t so much that I was dealing with a social issue as my subject. Rather, I wanted to drive the two main characters, and the actors, into a corner and see what would happen.

Concerning the sexual aspects, I guess they are a result of my interest in thinking about how the actors react at times when the voice of the loins intrudes unavoidably into what is otherwise restrained and proper conversation. It may appear humorous at times, and sad at other times. That is a reaction I am interested in seeing, so I guess it is true that I am writing the script so that such scenes are created. In that sense, the fact that I am also an actor may be revealing itself at a fundamental level in my writing.

This is because, especially when you are working as an actor in Seinendan like I did, Oriza-san will give directions to the actors such as, “If you turn this way at that moment and say nothing for five seconds, you will appear to be in sadness.” Of course, that kind of direction can build frustration in the actors, because we want to use that five seconds to do a more intense, high-level acting. At the same time, there is the enjoyment of acting as you are directed to by the director, and in fact acting as instructed does communicate that sadness to the audience effectively. Perhaps this may account for my interest in the sense of “being moved” or “manipulated” [as opposed to taking deliberate action]. - What was it that originally interested you in theater and becoming an actor?

- From the time I was a child, I did like to play out situations based on a certain assumption or imagined state. For example, children are often told by adults to “Eat your vegetables,” aren’t they? So I would think, “Isn’t the grass in the garden is a kind of vegetable, too,” and I would get my playmates to eat a wild grasses from the garden and then have to go with them as they got their stomachs treated afterwards [laughs]. If that kind of playing is the roots of theater, then I guess it is at the root of what led me to theater.

Also, when I saw my older sister act in an English-language production of The Glass Menagerie in high school. My sister played the role of the mother, Amanda, and it was very interesting to me. It is the same with Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire. I like watching troubled people like them who try to envelope the people around them in their own fabricated story. That led me to have our high school drama club do a production of The Glass Menagerie and I played the son Tom in it. That drama club wasn’t really very serious or interesting, and I myself had only joined it because there was a girl in it that I liked. Still, there were intense feelings involved [in the drama experience]. Tom is a narrator who is recalling events of the past. In other words, he is a character who is trying to create a new story but is unable to escape from the past. The overlapping and gaps between his story and the story of his troubled mother was very interesting to me. You have the mother, who stays in the house, and Tom who is striving to leave the house and then there is the daughter Laura who is trapped between the two and becomes reclusive as a result. I could feel a menagerie created there by the three characters with their individual delusions. - Then, when you went to university you joined a drama group there as well, didn’t you? Were there any playwrights or directors that influenced you while you were doing student theater during those years?

- At university there were upperclassmen who liked Shuji Terayama and Juro Kara, so I was always watching their type of underground theater. It was fun going to the tent performances and sitting on the ground watching the plays and using vinyl sheets to protect us from the water that was thrown off the stage, and things like that. There was something moving about the lines the actors spoke and there was a fascination with the bold ways that light was used and the way music was brought in for dramatic effect. So I never had any qualms about getting on stage and entering that strange world where people put on a black cape and silk hat, whitewashed their faces and moved in slow motion.

However, one can get used to that kind of [underground] atmosphere, so I began to wonder if there weren’t any other interesting things going on out there. That is how I discovered the theater works of Akio Miyazawa, Ryo Iwamatsu and Oriza Hirata. The worlds they wrote about, as well as the energy of the physical presence of the actors when acting out their plays, was completely different from the underground theater I had seen, and it made me feel that this is what I wanted to do. I especially liked Iwamatsu-san’s plays, and I even wrote one play in an attempt to copy his style. The title was “Iiwake Jinsei” (Life of Excuses) [laughs]. When I think about it, the things I am writing now may not be so different. People’s lives can usually be seen as involving excuses and I tend to continue to watch people who create their own stories in their lives. - You experienced the works of both the dramatic underground playwrights and the more restrained “quiet theater” playwrights who wrote in a daily conversational style. What made you eventually decide to chose to enter Oriza Hirata’s Seinendan company?

- Rather than any feeling of something in common [with Hirata’s style of theater], it was more out of a desire to encounter things I didn’t understand. The lines Iwamatsu-san uses are short and everyday conversational, but I also felt something poetic and intense in them. In contrast, the lines that Oriza-san uses are more hard-cut and cold, and I felt that I didn’t really understand them.

- By “cold” you are probably referring to the absence of obvious passion or immersion, aren’t you? Compared to your works that reveal desires and despair strongly, Oriza’s plays work those emotions in between the lines of daily conversation. In this way, the feeling of your works is different but in both cases yours are not plays where a story is told directly from the viewpoint of a single character in the play.

- I believe that Oriza-san’s way of looking at things is that people are never acting with firm intention as much as we would tend to think and that, in fact, people are moved into action by the effects of their environment or relationships. His plays are made up of very short spoken lines, but they are written so that each little pause has a strong effect in the relationships between the characters and the distances between them. That has influenced me a lot. Rather than summing up things in one direction, I want to show that we can’t really understand people, and I want to write that way.

However, I don’t write things like, “Wait three seconds,” or “Have everything happen at once.” While I do think it is interesting as a writer, Oriza san is such a firm pillar and has such clear beliefs that he is sort of like a father figure to me. I will never be able to transcend him by doing the same type of work, and when I am with him I get the feeling that I wouldn’t want to attempt that in the first place. But in fact, that sense is something that energizes Seinendan. It may be that we are all indeed “being moved by” him [laughs].

As for the “immersion” you mentioned, I hear that Hideto Iwai of Hi-bye, who is of the same generation as me, really likes the [late] singer Yutaka Ozaki, but I myself don’t recall ever getting really into something intensely in that way. I didn’t come along in time to get into the theater scene of the ’80s when it was at its peak with playwrights like Hideki Noda and Shoji Kokami. So I have always had a certain longing for that kind of getting intensely into something, which is why I like to write about things like cult religious groups or people with Utopia visions. But, when I write about them I don’t merely show them as fanatical, dangerous groups. Instead, I want to show the things on their reverse side as well. Those groups that get fanatical and do evil things certainly didn’t start out with the intention of doing evil. Perhaps they had good intentions at first, but those intentions got turned upside down and came out bad, or perhaps the way people looked at them changed. I want to present a full and jumbled mix of all those dualities or 3-sided realities. - So, is it safe to say that you don’t want to present one answer or head in some common direction but, rather, you feel more reality when you are setting up a fictional situation and depicting all the chaos that grows out of it?

- Yes. But that doesn’t mean I am taking a cynical approach. On the contrary, I think mine is a positive approach. Because even if you call it a portrayal of “dis-communication,” that in itself is not really an uncommon thing, and I don’t think it is a bad thing. For example, even if two people talk and are able to communicate well, that won’t change the loneliness they feel when they then go off and have to eat their meals alone. And, knowing that they share the same loneliness surely doesn’t make them feel that they are companions in that sense. So, it is OK to show both sides at the same time. I think it is alright that there are some people who want to be with someone and other who want to be alone.

- In 2010 you wrote and directed the lay Hakobune (Ark) for a production at the Kitakyushu Performing Arts Center, and you also wrote the play Seichi (Sacred Land) for director Yukio Ninagawa’s theater project for the elderly, Saitama Gold Theater. Are the things like this that you do outside of your work with Sample different in any way?

- It was decided in advance that the image source for Hakobune was to be the proletarian novel Kanikosen by Takiji Kobayashi. However, the relationship between employers and laborers today is not as clearly divided as it was in Kobayashi’s day. Today the employers are also employed by someone and the workers don’t have the kind of solidarity they used to have. So, I thought I would write about a more contemporary situation where the divisions between the two are blurred and solidarity is hard to achieve. But since I also used input I got from interviewing the local people who had been selected by audition to perform in the play, many parts of the play changed as I was writing it.

Seichi was influenced of course by the fact that there are 42 people in the Saitama Gold Theater company and by what I had seen of the interesting aspects of the elderly as performers that I had seen from watching the company’s third production, Ando-ke no Yoru (by Keralino Sandorovich). When you hear a story like that in Hakobune, you realize that there were probably people in it who had war experience, so you can’t make a story of your own out of it. So, I wrote Seichi purely with the illusions that came to a middle ground when I imagined what it would be like when I get old. Since I wasn’t going to be doing the directing, I made an effort to write things as clearly as possible with a clear structure to the story. Normally in my plays there are a considerable amount of warps in time and space and there are characters that you can’t really tell if it is a dog or a young girl, etc., so I decided to avoid those types of things [laughs].

Something I have realized recently is that with my work for Sample I don’t need to distinguish between myself as a playwright and myself as a director. In the past I felt that with regard to the things I had written I still needed to think objectively as a director, but now I don’t feel the need for such divisions [between the job of the writer and the job of the director]. In my plays the changing of scenes is often done merely through the actions of the actors, and there are times when I would rather have one scene morph into another gradually rather than having a scene change happen all at once. If I don’t do it that way I can’t give an accurate account of the progression and I can’t create the effect, or the world, that I want. So, if someone else tried to direct a play I wrote for Sample, it might be quite difficult. On the other hand, you might say that the fact that I don’t write things out clearly gives them more room for play. It could be presented any way the director wanted. - With the exception perhaps of the theater of the ’80s, I would say that you have personally experienced modern Western theater and the different trends through the history of Japanese theater from the underground movement to Oriza Hirata’s contemporary colloquial theater. Also young playwrights in their twenties today are gathering attention with works that make reference to pop culture phenomena like hip hop and comics. Within these trends, what direction do you think your activities will be moving in from now on?

- I feel with certainly that the experiments in method such as using musical type rhythm or using repetitions of a story that we see coming from young people today are different from what I am trying to do. So, I feel that my method of having actors, people, there and having them interacting with the space and things and getting ideas from the schisms and reverberations that result is something in itself that will not change in the future for me. However, I do want to do more exploring of how to depict “the Other” as they appear my works. In fact, having won the Kishida Award this time may turn out to be a turning point for me. I want to continue to show even more that “You and I have differences, but we also have things in common,” and I feel there are different methods for doing this than the ones I have been using until now.

For example, [playwright] Masataka Matsuda has written and staged a series of plays in recent years about the two cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that the atomic bomb fell on in WWII. In these works we see both the image of someone who can never be anything but an outsider with regard to the effects of the bombing no matter how hard he tries and also the image of someone knowing that fact and still trying to approach this subject, and I believe that this attitude is probably very important for theater. It is a method that doesn’t try to measure people by one’s own yardstick and show agreement or rejection of them. This is something I want to do more thinking about. In the process of working on this series, Matsuda-san broke down the world of theater he had built up until then and set off in a new direction toward documentary theater or exhibition-style theater. I honestly don’t know what direction I will end up moving in the future. But seeing a playwright change as much as Matsuda has, has given me hope and been an inspiration. - I believe that the changes that occur in a playwright reflect changes in that person’s view of theater and the audience and, by extension, changes in society. The fundamental appeal of theater, I believe, is that it deals with the here and the now. And, I believe that it is not enough to simply seek shared experience or romance. I think there is a need to look at the relationship with society as well.

- I don’t know if you would call it sociology, but I like thinking about what people rely on [spiritually] for living their lives and how the things that people rely on change. What is it that I depend on in order to stand here where I am? In other words, what are the standards I use for mapping myself? I believe there are some people who find it hard to hold such standards and maps and don’t think they are really necessary. But I want to hold them, even if they are self-made, and I am constantly searching for things than can serve as valid references for my standards.

Of course this is not a question of ideology any longer, and I don’t know if it will be technology or even social networks like Twitter or Facebook. But, I do believe that at least I can keep pursuing means of expression within that questioning and searching. It isn’t the role of the artist to tell people, “This is how you should live.” For example, I believe it is alright to show yourself honestly if in the face of something like an earthquake you become depressed and lost, or to show yourself vacillating before some greater power. So, I think it will be good for me to search for the kind of reality I can bring to the searching and vacillation of contemporary life.

Shu Matsui

Affirmation of the passive life,

the realism of Shu Matsui

Shu Matsui

Born in Tokyo, 1972. In 1996, Matsui joined Oriza Hirata’s theater company Seinendan as an actor. Later he began playwriting and directing as well. After premiering his plays Passage (winner of the 2004 New Playwright Award of the 9th Japan Playwrights Association Awards), World Premiere (2005, finalist for the 11th Japan Playwrights Association Awards), Basement (2006) and Shift (2007) in the independent production series for young Seinendan members, Matsui left Seinendan to start his own company Sample with an opening production of his play Calorie Consumption in September 2007. His plays have won acclaim particularly among those of his own generation for the unique twists they put on conventional values and the nihilistic worlds he depicts by breaking down the illusions of human relationships and communication. As the opportunities for his works to be performed abroad increase, his plays Shift and Calorie Consumption have already been translated into French and Basement has been translated into Italian. Matsui won the 55th Kishida Drama Award for Jiman no Musuko (My son, my pride) (2010). Recently, Matsui’s career includes an increasing number of activities outside his own company such as writing plays for other companies, including Seichi (Holy Ground) for the Saitama Gold Theater and Mirai wo Wasureru (Forgetting the Future) for Bungakuza. He has also directed plays in translation such a Sarah Kane’s Phaedra’s Love , written numerous short stories and essays, taught at the university level and appeared in television commercials, movies and plays.

After a period performing as an actor with Oriza Hirata’s theater company Seinendan, known for its contemporary colloquial drama style, Matsui started his own company Sample in 2007. The next year’s Kazoku no Shozo (Family Portrait), which can be seen as a prequel for Jiman no Musuko, drew attention for the way it portrays seemingly unrelated “samples” of the daily lives of a reclusive son and his mother, a part-timer, a convenience store manager and other self-injurious characters representative of the twisted side of contemporary Japanese life so realistically. This interview explores Matsui’s (born 1972) vision of contemporary life and the possibilities in expressing it and asks about his personal background.

Interviewer: Rieko Suzuki

The newest play by Shu Matsui is coming on 2011/7/1-7/10!!

English subtitled on 7/9 14:30&19:00

At Gehena

(Inspired by the novel The goddess and Toka-ton-ton of Osamu Dazai)

Venue: Hoshi-no-hall, Mitaka City Arts Center

https://mitaka-sportsandculture.or.jp/zaidan/access/

July. 1 (Fri) 19:30

July. 2 (Sat) 14:30&19:00

July. 3 (Sun) 14:30

July. 5 (Tue) 19:30

July. 6 (Wed) 14:30&19:30

July. 7 (Thu) 19:30

July. 8 (Fri) 19:30

July. 9 (Sat) 14:30&19:00 (English subtitled)

July. 10 (Sun) 14:30

3,000 yen *Tickets purchased at door are + 300 yen to Pre-sale ticket price.

Available per http://mitaka-art.jp/ticket/ or PIA 0570-02-9999 (P code: 411-899)

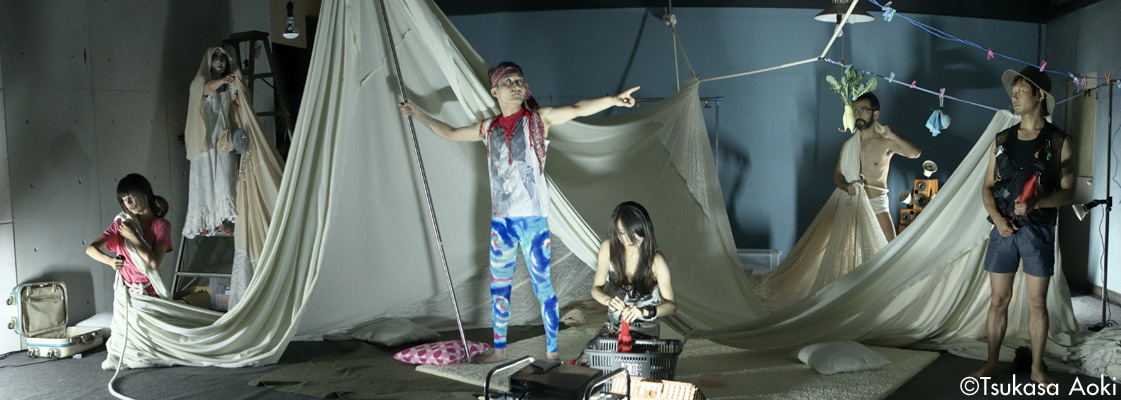

Sample Jiman no Musuko

(Sep. 15 – 21, 2010 at Atelier Helicopter)

Photo: Tsukasa Aoki

Sample Kazoku no Shozo

(Aug. 22 – 31, 2008 at Atelier Helicopter)

Photo: Tsukasa Aoki

Kitakyushu Performing Arts Center production Hakobune

(Feb. 23 – 28, 2010 at Kitakyushu Performing Arts Center-Small Theater)

Photo: Gen Fujimoto

Related Tags