- It is now 25 years since you started the Gekidan Kenko theater company in 1985. That puts you in the veteran league among today’s playwrights and directors. Nonetheless, you continue to produce a great variety of new works, many of which seem to be opening up new possibilities for Japan’s contemporary theater. For someone to start out as a musician like you did and then become a playwright and director is almost unprecedented. Could you begin by telling us what led you to start a theater company?

-

The person who continues to work with me today in my theater productions, Inuko Inuyama, used to be a member of our music circle and do our stage makeup for us when we were performing as a band. At the time she was doing music as she studied to be an actress, and when, just for fun, I wrote a skit for her to perform at culture festivals, it somehow developed into the idea of starting a theater company. That was just around the time when companies like Shoji Kokami’s Daisanbutai were beginning to become the focus of attention on the theater scene. And, although they weren’t mainstream, Akio Miyazawa’s Radical Gajiberibinba System and the recently launched Wahaha Honpo were two comedy companies leading one sector of the theater scene at the time. They were completely different, one stylish, one down home, but they kept me going to the theater once every two months or so. In the process, my interest was staring to shift toward theater.

It was just at that time that I was asked if I wanted to form a theater company, and we had the rather calculating idea that our band’s fans would be enough to fill the seats for a theater performance (laughs). Then we did a play as the maiden performance of the new company, which was financed with my private recording label, Nagomu Records as the producer. It was a kind of makeshift arrangement, and I didn’t think at the time that I would continue doing theater for very long. And in fact, in the early performances most of the audience was indeed made up of our band’s fans. - How did you come up with your very non-Japanese artist’s name, Keralino Sandorovich?

-

It is a name that one of the upperclassmen in my high school drama club gave me, and it also became my nickname in our band, Uchoten. Then, when we were making the leaflet for the performance commemorating the founding of our theater group, I needed a name to use and decided to use Keralino Sandorovich temporarily.

I like the Marx Brothers very much, and in their films, for example Groucho always used long, ostentatious roll names like Dr. Hackenbush or Rufus T. Firefly. As for Chico, since his specialty was acting with an Italian accent, he would use a name like Chicolini. I guess it was an unconscious copying of those names that led me to use Keralino Sandorovich. But I don’t remember much. And, when doing comedy routines it is more interesting to have an ostentatious name like that (laughs). - Now that you have mentioned the Marx Brothers, it seems to me that a lot of your works are based on films and music and literature that you were familiar with from your childhood. To understand this better, could you please tell us something about your childhood? We hear that your father was a musician.

- Yes. My father was a jazz musician, and I believe that had a big effect on me. Among his friends were leading comedians of the day, like Toru Yuri and Shin Morikawa, and we also have a photograph taken of me as a little child held by Enoken (Kenichi Enomoto). The sound of jazz playing was always a part of life in my childhood, and when I was in elementary school I saw a performance by Eiichi Ono on Shinji Maki’s TV program “Taisho TV Yose.” His thing was doing takes on Chaplin and it was from watching him that I first learned about Chaplin. Just after that there was a showing in Japan 10 revival Chaplin films series called “Viva! Chaplin” and I went to see Modern Times . That got me hooked on Chaplin. It was a completely different world from the ones in the popular movies of that time like The Exorcist or Enter the Dragon . It was silent movies in black & white with music somewhere between jazz and classical playing through the entire movie. But they succeeded in making you laugh without the use of words. It attracted me as a kind of dream world and I was really taken by it.

- So, that was your first encounter with silent movies.

-

The next thing I got into was Buster Keaton. At the time they had just found some Keaton film negatives that were thought to be lost and we finally had the full Keaton works again. As a result a showing was made of the full dozen or so Keaton works in Japan that drew the attention of college students and others at time. I was still in the 5th or 6th grade of elementary school, but during the summer vacation and holidays I was spending all day at the movie theater. The woman working at the concession stand there got to know me and gave me crackers sometimes which made me happy. She told me she was worried that I was spending the whole day at the theater not eating anything.

It has always been my nature that when I discover people like Chaplin and Keaton, I naturally want to find out what other artists there are in their genre. So, I would go to used book shops and look at old movie magazines and learn that after Chaplin comes Harold Lloyd, and after Keaton comes the Marx Brothers in the talking pictures, and in the process my knowledge and world of interests gradually expands. - Is it true that you had your own collection of silent films when you were young?

- I got so into silent comedies that I began buying films that only real maniac collectors knew from the US, Germany and Italy via importers. Once I even withdrew 2 mil. JPN (approx. 22,000 USD) from one of my father’s long-term savings accounts to buy films. That really got me in trouble when he found out about it! By the time I was in middle school, I was renting places to organize movie showings from my collection. When adults came to see the films, they would ask me if I was helping out my father. It was a bother to try to explain that it was my collection, so I would just answer, “Yes.” (Laughs)

- Among the artists of that period, it is Keaton that you liked best, isn’t it? It seems that Keaton is still at the base of your working style today.

- I don’t know if it is calculated, or if it comes naturally from his character, but in Keaton with his un-solicitous comedy, there is a cool and somewhat melancholic atmosphere, isn’t there? Chaplin was the original reason I came to love silent movies, but the more I came to know, the more I was attracted to Keaton and the Marx Brothers, in other words the ones whose comedy was at the opposite extreme from humanism, with an aspect of anarchy. If it weren’t for Buster Keaton, the Marx Brothers and Monty Python, I wouldn’t have continued to do the work I am doing today. And from about the age of 30, Woody Allen joined this list for me.

- You went to high school at the Nihon University Tsurugaoka High School and were in the drama club there. It is a famous school for drama in Japan. Can you tell us what plays you did there?

- Due to the influence of our teacher, we did mostly plays by Beckett, Pinter, Minoru Betsuyaku and Kunio Shimizu. We also did a Kobo Abe play. So, I couldn’t understand the plays at all (laughs). But the book by Betsuyaku that our teacher told us to read was so humorous that it made me burst out laughing as I read. When I use the word kudaranai (stupid, nonsense, ridiculous), it is usually with a positive meaning, and as I read Betsuyaku’s book I remember thinking, “How could someone his age think about such ridiculous things.” But when I actually saw his plays performed, they were staged with the dark mood of theater of the absurd and the ridiculous absurdity was lost. I felt that it would have been better to do a more straightforward presentation of the absurdities and misunderstandings and mishaps that could bring out the nonsensical humor in it as well.

- In the production of Betsuyaku’s Byoki (Sick) you directed in 1994 you cast the well-known radio DJ Katsuya Kobayashi in the role of middle-aged office worker who is needled by a strange nurse in a nonsense comedy style staging what seemed to completely overturn the entire history of interpretations of Betsuyaku’s play. From what I hear, it appears that you already had that type of theater in mind when you were in high school. But, despite having done theater in high school, you went to a vocational college for film after graduation.

- Since I had gone to a Nihon University affiliated high school, I had intended to go on to Nihon University. But when the time came to take the entrance exam, I was sick in the hospital. Just after that I heard an advertisement on late-night radio with Shoichi Ozawa saying, “If you failed to get into college, come to the Yokohama Academy of Broadcasting and Film,” and I said to myself, “OK. I’ll go.” (Laughs) The president of the academy was the film director Shohei Imamura. The pamphlet I sent for had the words, “You’ll probably never make a living in movies, so get a woman to support you.” It turned out to be a pretty unique school. That let me know from the start that the world of film was no ordinary world.

- In the Japanese movie world there were veteran directors with a good sense of comedy like Kihachi Okamoto, but were there any directors that influenced you particularly?

- Kihachi Okamoto did, and so did some of the works of Yuzo Kawashima, Ko Nakahira and Kon Ichikawa. There were some works that I thought were really cool. I also went to places like the Film Center. Among the things I liked were Yuzo Kawashima’s Kashima Ari (We have Vacancies) and Bakumatsu taiyoden (Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate) which ends at a cemetery. I thought the kind of artist who didn’t try to show the dark side of life as tragedy but dryness was cool.

- Still, you didn’t go into filmmaking.

-

The movie was a system that the more you knew, the more negative you became. Japan’s movie industry back in those days was still the kind of world where you worked for years as a director’s assistant and if you were lucky you might be able to direct your first movie after ten years or so. Even then you would probably be told to direct something you weren’t interested in at all, and if it didn’t sell, that was the end of your career as a director. I had experiences where my seniors would tell me that the subjects I was interested in were weird, or that I had to have a clearer thematic concept, and those experiences made me disillusioned with the movie world.

On the other hand, it was also a time when bright young directors like Sogo Ishii with his film Burst City , and Makoto Tezuka with his 8mm film MOMENT were drawing attention, and the PIA Film Festival had just begun as a platform for independent filmmakers to win recognition. However, even with these new developments, the chances for success were still few, and it also happened to be the time “indies” (independent) bands were becoming the trend. - Did you play an instrument at that time?

- I didn’t. Even though my father was playing acoustic bass, it seemed like a lot of noise when I watched them perform. At that time in Japan, the use of synthesizers and techno-pop using computer-generated sound had just begun, and representative of that trend were YMO (Yellow Magic Orchestra) and the punkish-techno group P-MODEL, as well as the group Plastics formed by graphic designers and stylists and the band Hikashu with Koichi Makigami (who used to be an actor of rock musical company Mr. Slim Company) as its lead singer. There had been the punk movement and afterwards came the New Wave and Techno booms that carried on the punk spirit with new technology. Among these there were some people from art school who created “instruments that they can’t play” as their expressive medium, which I found quite stimulating. I began to think about doing punk music myself, and gradually my inclination drifted away from movies. All you needed to start a band was to bring together four or five people. Then, once we started performing the response was unexpectedly good and we soon had a following of strange fans. So, we kept performing as a band without really thinking about the future.

- In that band, Uchoten, you not only sang vocals but also started a recording label that led the “indies” scene and managed to make a mainstream debut. Wasn’t your father rather pleased to see you active as a musician?

- He was a shy and reticent type, so he never said that to me directly, but after he passed away I heard from one of his friends that he had said things like, “My son may have even more talent than me.” I was 27 when he died, but he had been sick for about three years before that and we had been told that he only had two or three years to live. So his death didn’t come unexpectedly.

- While you were caring for your father in the hospital in 1988 you wrote Good Morning Colorful Mary – Another Morning of Light Fatal Wounds . That work seemed to be an important turning point in your career as a playwright. It is nonsense comedy dramatizing a breakout from a hospital played out simultaneously with a story about an old man suffering from dementia. I found it a very moving work that deals with the theme of death but dealt with in a way that the depth of its sadness also creates an equally proportion of opportunities for laughter in the context of a series of normally impossible events. I believe that was the first play you wrote about experiences from your personal life, and I don’t know of any works you wrote in that way since.

-

At the time, that was probably the only subject I could have written about.

After Good Morning Colorful Mary there were some definite changes inside me. I don’t really like American healthy, non-sarcastic comedy. I like British self-deprecating humor. And I feel that at that time I became able to think about why that is so by connecting it to the life I was living.

The deeper you analyze self-deprecating humor the more you realize that life isn’t all fun and happiness, but we still live on. You accept the fact that since you have been born you might as well live and do things. I think that’s what it is. By writing that play in that style, it provided me with an opportunity to face myself in that respect. - In 1992 your Gekidan Kenko theater company disbanded and in ’93 you switched to the theater unit Nylon 100°C. What was the reason for that change?

-

Although there were some exceptions like

Colorful Mary

, Kenko was primarily a team that specialized in doing nonsense comedies. My goal was Monty Python. One of the reasons for the disbandment was that I was beginning to see the limitations in continuing to do the same kinds of works. I started to feel lost what is really funny. It might be that the funniest thing would be nothing happens in the drama. (Laugh) Considering the very equivocal in nature of criteria for judgments about the quality of a play, or the quality of actors, I was personally wondering if it couldn’t be possible to adopted a wider perspective and do a variety of different kinds of plays from based on different senses of value. That was the idea behind launching Nylon 100°C.

For example, the first play we did as Nylon 100°C was pretty similar to what we had been doing in Kenko, but the second play, SLAPSTICKS , combined critical biography and melodrama aspects, and after that we were so encouraged that we began doing works that experimented with all possible kinds of dramatic expression and staging. - After launching Nylon 100°C, you began to produce more works—as many as five or six a year—that were also quite varied in nature. There were your old type of nonsense comedies, critical biographies, science fiction comedies and very serious tragic comedies. Such variety in works is surely rare for a playwright.

- I do such variety because I am scared of getting bored (laughs). Also, it is not that I think there is no such thing as failure for me—because there are times when things go well and times when they don’t—but I feel that rather than not doing things for fear of failure, it is better to try a lot of things in hopes that afterward I can look back and feel that some of them went well. I believe that every time I get a spark of inspiration for a work, I should follow through on it and bring it to the stage. If I didn’t think this way, I don’t believe there is any way I could produce as many works as I do.

- When you create a work, what kinds of things inspire you, and what is your working process to bring a work to completion?

- There is no process, it is just a hectic rush right up to the moment the curtain rises on opening day (laughs). Take my latest work “Tokyo Gekko Makyoku” (Tokyo tale of moonlight magic), began from film footage of Japan in the early Showa Period (beginning from 1925) that I happened to see on YouTube. The film was in color, which means that it was taken by a foreign visitor to Japan, because there was no color film in Japan at the time. The footage of places like Asakusa in Tokyo had been well maintained and was in very good condition. I was also inspired by reading copies of the magazine Shinseinen , whose contributing writers included people like Junichiro Tanizaki and Edogawa Ranpo before they became famous. They were full of the vitality and creative energy of prewar Japan and they made me imagine that would be interesting to write a detective story set in Tokyo in that period. When a few things like this come together by coincidence, they have a strong effect on me and push me to create. It is not that I have a special belief in fate but I do feel that materials for a work come together naturally for me.

- In 2001 you wrote the critical biography Kafka’s Dick and last year you presented a trilogy of plays based on Kafka’s three novels The Trial , The Castle and The Castaway/Amerika , and the three plays were performed together as “Setagaya Kafka.” Judging from this, Kafka would appear to be an important influence for you. Did you read his works from your high school years?

-

Yes, but I first didn’t understand much of what I was reading. And I fell

The Castle

by the wayside many times. What stays with you after reading Kafka is not so much the story as a certain scenes or situations, don’t you feel? For example the scene of the courtroom packed with people or a scene of bankers being concentrated on typing at the typewriter, or a scene of people being whipped in a company warehouse. I was the kind who liked scary folk tales or children’s stories and I think I read Kafka as an extension of such stories. I also liked (Gabriel) Marquez, Tove Jansson and, of course, the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales.

Kafka’s Metamorphosis was short and easy to understand, and as usual, once I read it I wanted to know what other things he had written, so I went on to read his other works. It surprised me at the time to find that Kafka died at the age of 40 without ever receiving recognition as a professional writer and that we only have his works today because of his friend Max Brod. That, in turn, fed back into my reading of his works. Kafka’s life was so mysterious itself and attractive so as himself. When you read collections of his letters you find that he had his human side and then an inflexible, selfish side that led to failings, and that was interesting to me. - Among your plays there are many in which you have the comedy on the one hand but at the same time you have a world that is steadily falling apart. Some representative works of this type are your 2003 play Harudin Hotel , in which the situation of a hotel celebrating the 10th anniversary of its opening is used to show the “10 years later” state of the original guests who stayed there on the opening night, and your 2004 play Disappearance in which the main characters are two brothers living in the world after “the war to end all wars.”

-

I guess I just have a hard time being optimistic that things will get better in time. When people of my generation were children there was a feeling that the 21st century would be a wonderful world where everything was rosy, and that was supported by positive images in our culture like the “Atom Boy” anime series, but as we grew older the predominant feeling was that things would actually not get better. I think that perhaps the last symbol of the brighter world to come was YMO. But even at that time, I think many people were listening to their techno-pop music with a feeling that there was something fake about it. After that, I felt that it wasn’t right to be optimistic and have hopes for the future. That may be why I am attracted less to ideas of Utopia and more toward Dystopia.

In terms of human relations too, I tend to write mostly about cruel situations where people’s good intentions in fact turn out to have bad effects, and my interest lies in how the characters then deal with those situations. This may be because I was often troubled by human relations when I was a child. For example, if there is a person A and person B present and the three of us are talking, but then, when B leaves and A starts talking about B in a different tone, I would always have trouble dealing with that. I think this may be a trivial thing that all children feel, but I probably had more trouble with it than my friends.

For some reason I never forget those experiences. And I will use those incidents in the plays I write now at lease once to get a laugh. I get the feeling that I am clearing up past debts so to speak by turning those things I couldn’t solve or the things that hurt me as a child into comic devices. - Watching your plays, I get the feeling that all of the characters have two faces, the face they show to others and another inner face. It feels as if the script might also be written with two separate lines for the outer face and the inner face and the choice of which line to deliver would change the course of the plot development; as if saying, “In this situation we will bring out the outer face, so use this line.” Do you have that type of sense regarding the characters’ faces?

-

Ryo Iwamatsu

, for example, says that people don’t say what they are thinking. The spoken lines are a relative thing because people don’t put their thoughts in words like they did in Shakespeare’s day. I believe there is truth to that but, on the other hand, I would tend to take an eclectic approach and say that isn’t it in fact a matter of degrees. People say things they believe and they also say things they don’t believe, so is there really a need to say it is one or the other? And that approach may take on the appearance of presenting an outer character and an inner character.

However, when I am directing actors, I stress the fact that people don’t necessarily say what they think. I say that because actors have the tendency to equate the lines of the script with emotions. Or they tend to take extreme interpretations such as believing that the lines are meant to be deceptive because the character is in fact telling a lie. I guess I prefer a looser stance in which I might say to them, “It is actually something more vague,” or “You often don’t really know the real meaning of what you are saying at the moment you say it.” - You have written some works like Disappearance that involve only a few characters, but most of your plays involve larger groups of characters. Is this something that you do for a specific purpose?

- It is easier for me to write a play involving a larger number of characters. When presenting a specific moment in time, for some reason I have a reluctance to letting one character carry too much of its specific gravity. When the final curtain comes down there is some degree of conclusion to the story. However, rather that thinking of that as the complete conclusion to everything, I always have the feeling that things will continue after that. It may sound strange to put it this way, but I write a play with a sense that the falling of the curtain is a tentative ending of sorts and beyond that point I still take responsibility within my own mind for the ongoing existence of the characters that I have introduced.

- Last year you wrote the play Ando-ke no Ichiya (One night of the Ando family) for the senior-citizen theater company Saitama Gold Theatre. It is a play involving a large number of characters in a story about an aged teacher and the former students that have gathered around him in his final days. There is foolishness and there are desires, and there is also a magical world combining elements of the real and the unreal that appears rather Fellini-esque in flavor. Ninagawa ’s directing was also outstanding, but I was moved greatly by your wonderful script as well. It must have been very difficult for you to write parts for all of the 42 middle-aged and elderly actors in that play.

- I don’t feel that I fully wrote the parts individually for each character, maybe half. In fact, the script wasn’t finished when it should have been, so I had them send me a DVD of them working in their studio rehearsals and then wrote the parts for the people as I saw them. But, actually it is much easier to write that way for a large group of 40-some actors. The play turned out well because of the strength of the actors. It is not a matter of acting skills but of human strength, I feel.

- In the last few years you have written a couple of plays about writers, including the 2007 play Waga Yami (My darkness), where one of the main characters is a novelist, and the 2008 play Sharp-san and Flat-san , involving a playwright no longer able to deal with the changing times. Do their stories overlap with your own life in some ways?

- Of course they do. There is the well-known expression for writers that if you fall into a writer’s slump you can always write about a writer in a writer’s slump. But I had always thought that writing about not being able to write is an act of admitting the fact that you are unable to write, so I had always avoided bringing writers into my plays as characters. However, once I accepted the simple fact that writing about a writer rather than about a person in a profession completely different from my own offered more possibilities for insights, I was able to write about writers without any of the old fears. In the case of Sharp-san and Flat-san , it was not the idea of writing about someone who can no longer write but the idea of writing from the perspective of “What if I had not become a writer and had taken some other path in life?”

- Earlier you spoke about being part of a generation that finds it hard to be optimistic about the future. Playwrights Suzuki Matsuo and Oriza Hirata are of your same generation. Do you find any things in common with these writers?

-

I believe there are things we have in common. I believe it is the same as with contemporaries in the rock world. For one thing, we were watching the same plays by Kohei Tsuka

and Shuji Terayama

at the same time in our lives.

I lived in the Ebisu district of Tokyo as a child and Terayama-san’s Tenjo Sajiki theater was in our neighborhood. When I was in middle school I often walked down Meiji Avenue to the Aoyama district to see Tsuka-san’s plays at the VAN 99 Hall. I first saw a Hideki Noda play, Niman Nanasen Konen no Tabi (A 27,000 light-year journey), when I was in high school. But, as for angura (Underground) theater, I thought it was amazing in some way but I never felt that I wanted to be like them. I felt that I was different from them.

The company “Radical Gajiberibinba System” that I encountered later was purely live versions of Monty Python-type comedy. The fact that both Suzuki Matsuo and I were inspired by them is evidence that we shared some of the same sensibilities. But he is someone with full of complexes who was driven to quit his job as a company employee and leave his home in Fukuoka to come to Tokyo on his own and make his career, while I am someone who was born and raised in Tokyo, where I could see anything I wanted. He overcame adversity and used that as his impetus, while I never had any adversities to overcome. I look at his work and see how he is able to create plays based on his own life. And I realize that I never had the complexes that he has as a result of his life. So I was jealous with him in that way. Well, you could say that as Tokyoites our only strength is in being raised in Tokyo, so we have to make the best of it. But, although we both have our successes and failures, when I see at Matsuo-san’s works I get a clear feeling for the things he is trying to express and I realize that it is based in shared sensibilities of our generation. He has been such a playwright I believe in the most. - If you were to put it in words, how would you describe some of the sensibilities you two share as members of the same generation?

- I think the first to give form to it was Oriza Hirata-san with what came to be called “quiet theater.” And what it was is something I believe to be an inherent embarrassment or sense of shame at being on stage in the name of theater. Matsuo-san has also said something to the effect of, “I can’t believe anyone who can stand on stage without a sense of embarrassment.” On the other hand, Noda-san, for example, seems to me to be someone how overcomes that embarrassment by experiencing the momentum of things like word play and dynamic movement on stage. That is something we of the next generation can’t do. We were only able to approach theater mentally and try to succeed on the strength of our sensitivities and ideas while admitting that we knew our limitations. I think this is a consciousness shared by many people in Japan born around 1962 – 63.

- How does that “sense of shame” actually manifest itself when you are creating a work for the stage?

- In my case, it begins with asking the actors to give up the idea of any unnatural posing on stage as a part of their approach to theater. Since I value words, I want to eliminate any unnecessary movement on stage as much as possible. From the beginning when I first came to the theater field, I always want the actors to have a consciousness of avoiding unnecessary movement and unnecessary appeals to the audience, to the degree that that is possible.

- Listening to what you say, I get the impression that your experiences from the media lie at the base of the worlds you create in your works. And many of those experiences apparently came at a very young age from a wide range of media, both old and new that you were able to absorb. It seems to me that it is the ability to utilize these experiences as resources for your creative process that makes you unique as an artist.

- In fact, I suffered seriously from asthma until the age of five. Around the age of one the doctors said I might not make it, but apparently I survived. If I was considered a precocious child, it was probably because I was mostly bedridden until the age of five. While the other children were outside playing ball, or building plastic models and playing with soccer games, I was at home in bed, where my world was only television, music and books. And, since I never gained the physical coordination a child would normally acquire in those early years, when I went to elementary school I couldn’t play like the other children, so once again I turned to books and films. I believe that is why I had a special ability to concentrate, if I do say so myself. And, I believe that the things that I absorbed during those years have an especially big influence in my creative process as a playwright and director today.

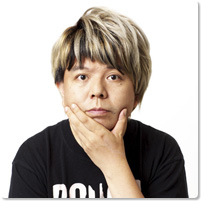

Keralino Sandorovich

Serious postmodern comedy Keralino Sandorovich

Keralino Sandorovich

After graduating from the Yokohama Movie and Broadcasting College (now the Japan Academy of Moving Images), Keralino (aka Kera) formed and sang lead vocals for the new-wave band Uchoten. While at the forefront of the indie music boom, he also established the theater company Kenko, which presented mostly nonsense comedies from 1985 – 92. In 1993, he formed his present company, Nylon 100˚C, for whom he writes and directs most of the performances. Their regular members are joined by various guest artists who stage concept-oriented performances called “sessions,” and in addition to nonsense comedies they perform a wide range of live-style works incorporating sitcom, dance, film and skits, and even a Western performed by an all-female cast. In 1999, Kera won the Kishida Drama Award for Furozun bichi (Frozen Beach) . In 2002 he won the first Asahi Performing Arts Award, and also in 2002 the fifth Tsuruya Nanboku Drama Award and the 9th Yomiuri Theater Award for Best Director for Shitsuon~Yoru no ongaku (Room Temperature: Music of the Night).

(Interviewer: Akihiko Senda)

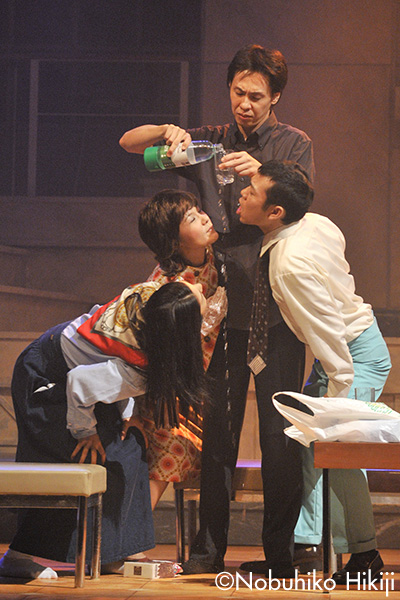

Nylon 100°C 34th Session

Setagaya Kafka

Written and directed by Keralino Sandorovich

(Sep. 28 – Oct. 12, 2009 at Honda Theatre)

Photo: Nobuhiko Hikiji

Nylon 100°C 32nd Session 15years Anniversary, Double casted play

Sharp-san, Flat-san

Black team (above)

White team (bottom)

Written and directed by Keralino Sandorovich

(Sep. – Oct., 2008 at Honda Theatre)

Photo: Nobuhiko Hikiji

Related Tags