- About how many theater companies are you doing stage art planning for today?

- The companies I design and plan for on a regular basis are Doubutsu Denki, which I’ve been involved with since college, potodo-ru, the group that first got me involved seriously in stage design, and then there are Heartland, Gring, Ashitazukan, Niwagekidan Penino, Tokio Swica, Harahoro Shangrila, Otona no Mugicha, Theatre Gekidango and Tokyo Kandenchi. I think that most of these relationships are with a certain type of artist or director who are interested in exploring and depicting the things that are revealed in human relationships.

- These companies you list are many of the young theater groups that are in the spotlight today. About how many productions do you work on a year?

- I was doing about 20 a year, but that suddenly soared to about 30 from last year. And it looks like it is going to increase again this year. It would be OK if the jobs came at an even pace, but when you get several in the works at the same time I feel like it will kill me sometimes (laughs).

- That is amazing. Many stage designers just do the initial plan and then hire someone to do the actual production work. What about you?

- Most of the stages I do are for small theater productions that are on small budgets, so I do everything myself, from the set planning and drawing the blueprints to buying the materials and putting the sets together. It is hard for me to give up the joy of the actual making of the set, so go to the workshop and do the carpentry and I paint the backdrops myself. Even when I do outsource some of the work to a set-making company, there is never a large enough budget. So I sometimes go along and help with the work in order to cut the cost. In all, I guess I do about 70% of the work myself. Of course I don’t have the time to make the smaller props.

- We hear that you are mostly self-taught. Could you tell us how you actually get started in stage design?

- When I was in theater in high school our club made it to the national high school theater contest with a production of Koharu Kisaragi’s Moral. We all did the acting and the set making together, and when I look back on it now, I realize that even back then I enjoyed thinking about how to fill a space and I remember taking the lead when we would get together to build set components like an objet pieced together from sections of water pipe.

I went on to study in the drama and theatre arts course of the Literature Department of Meiji University. I went to college imagining that the students there would be doing really interesting plays, but when I got there I was disappointed to find then doing regular drama and comedy stuff. At the time, I thought theater was supposed to be artistic and conceptual, and in art as well, I preferred abstract works. Still, I wanted to find people to do theater with, so I spent two years in Katsugeki Kobo drama club, a group that seemed to be having the most fun doing theater of the various drama circles at our university.

In the club, everyone double-roled as actors and stage staff, and in my case I doubled by doing publicity art or set-building. After that, I helped out at the Doubutsu Denki company that my upperclassman Taishi Masaoka founded in 1993 and was also active with a theater unit of my own. Around the time I graduated from university I had the vague idea that I wanted to continue in theater but I didn’t know exactly what I should do. When returned home to Gunma I found that I had a desire to study design, so I took the correspondence course in Design from Musashino Art Jr. College. But, it’s not as if that is really helping me in stage design today. I had to teach myself almost everything I know about stage art, by learning how to draw blueprints and going to help out at professional design shops and such.

At the time I was taking the correspondence course, I happened to be asked to do the set design for potudo-ru’s second production Uramimasu in 1997 because one of my underclassmen in the Katsugeki Kobo club was a high school friend of potudo-ru’s Daisuke Miura. That was the first stage design job that I actually got paid for, even though it only amounted to my travel expenses to Tokyo. - What kind of set did you design for that production?

- The setting for Uramimasu was a Japanese tatami room in an old apartment that would usually have two rooms with a small kitchen consisting on little more than a sink, a gas range and a cabinet. It was a one-act play based on just one situation. At the time I didn’t know if plays staged in everyday situations like that were beginning to be popular, but people from other companies who had seen Uramimasu would come to me after that and say that they wanted the kind of “real” set I had done for potudo-ru. And it has just continued that way until today.

In fact, at the time I felt an aversion for the kind of “real” single sets that I was being asked to do. It wasn’t that the sets weren’t interesting to make but that I wasn’t interested in those kinds of [one act situational] plays. I believed at the time that doing things like putting together found objects or a junked car and creating an abstract objet or taking a net and encircling the whole stage and audience space was more what stage art should be about.

It was a dilemma for me because as I worked I was thinking that “real” sets were something anyone could make. If you need a tatami room you can just bring the tatami from your home as it is. Where is the originality in that? So, when I did happen to get a request for an abstract set, I was determined to prove that I could do abstract sets too (laughs)! - When did you start to feel that that had become your style?

- Looking back, I think it was the potudo-ru play Knight Club in 2000 that was probably the turning point. [potudo-ru’s] Miura-san will probably get angry at me for saying this, but that was the first of their plays that I really found interesting. Until then I had tried to imaging why Miura-san had chosen a particular place as the setting for a play, but it wasn’t until Knight Club that it finally all made sense to me. Until then I had only though about making the kind of place I saw described in the script and the footnotes, but with Knight Club I felt for the first time that there was this one and only space that was absolutely essential to the dramatic development of the play and that it was my job to create that space.

- In potudo-ru’s Ai no Uzu (Whirlpool of Love) [see photo, see “Play of the Month“] and Yume no Shiro (Castle of Dreams) the stage sets are room spaces that also have very specific multi-functional aspects, like a condominium room with a loft or an apartment with a bath room in the middle of the stage.

- It is not only with potudo-ru. Most of the productions I do sets for are performed in small spaces that don’t even have stage wings. Within that limited space you have to satisfy the numerous demands of the director. So, of necessity it becomes a multi-faceted space. It is a process of considering how many of the desired elements you can fit into the space and I begin by doing sketches while imagining the lines of movement of the actors.

For example, with Ai no Uzu Miura-san said he wanted a place off to the side with a counter like a waiting room at the entrance where a club employee would be stationed and a living room in the center where the clients would gather and a playroom off of that. And I was like “Wait a minute! You know the [small] width of the stage at THEATER/TOPS!” (laughs). But he also asked me what elements would be necessary from a stage art perspective, so I was able to give my own input as we decided what form the stage would finally take. Miura-san is the type who wants to fill every available space with something, to the point that people say he has an “open space phobia.” He would forever be bringing in things like posters he has found to paste on the walls or some little prop to place in any open space he might find. Lately he seems to been cured of the tendency, though. (laughs)

Since I have never done designs for really large theaters it is hard to make comparisons, but I believe that small-theater one-act play, if you fill up a space with objects to the degree that there are no possibilities for the “place” to shift in nuance depending on how it is used, then it loses a lot of the interest that it could otherwise have. That is why I design the limited space itself with as much potential as I can. When I show my blueprints to the carpenters they often say, “You are really pushing it!” I want to use every possible inch of the limited space so people will come away saying that they never knew how large that little theater actually was. So, in the end I am laying out the spaces not in terms of feet but in terms of fractions of an inch. [The basic unit of the traditional Japanese measuring system, the shaku, is still used in carpentry and is almost exactly the same as the English foot] If I don’t do that, I don’t feel that I am making full use of the theater. There is no “backyard” in a small theater, so I often make the stage directors cry for the lack of unused space. But I do my best to designate spaces that are large enough for people to pass through or spaces where a cart can be placed to hold props. Of course, besides working as much into the space as I can, I also go through the process of eliminating things that are not necessary as well …. - When we watch plays using sets that you have designed, we often feel that we are right there watching the plot developments, up close to the actors, as if we are peeking into their world.

- It is the close proximity of the audience to the stage that gives small-theater plays their unique tension. So, you might even go so far as to say that that I have to pay attention even to the places and things the audience doesn’t see, and I want to be discerning about the details of everything the actors come in contact with on the stage. These are things I can’t compromise on. To achieve that level of attention to detail also requires technical skill, which is why I go to work part-time at the set-making companies from time to time and hang around while the construction work is going on to absorb as much as I can.

- Do you go out in search of materials to use for those set details?

- Sometimes I do. For example, when I was working on potudo-ru’s ANIMAL I made a set that included a wall under a bridge full of graffiti (see photo). I thought that I had better take the opportunity to study the technique of the guys who do graffiti in places like Shibuya, so I went to copy some of their work. And in everyday life I am always noticing details. Like if there is a particularly interesting stain [on a wall] I study it until I realize how it was made. Or, I find myself studying the details of the finish on the pillars in a building or thinking about what material I could use if I had to make a one-legged chair. I am constantly thinking about such things unconsciously. Often it’s more a process of just constantly noticing these kinds of details as I walk the streets, rather than specifically going out to look for details for a specific work. People often tell me that that habit of focusing on details is my occupational obsession.

- People often describe your style of set design as “real sets” but it seems to me that that expression is somewhat off target.

- I agree. It is true that I do bring together real materials and objects into a kind of collage, but the point is not that the final set look just like the real thing but that I create a realistic but fictional set that takes the real thing as a point of departure to create a performance space. For example, the layout of the rooms of a condominium will have a certain order with regard to the location of the entrance hall and the kitchen, etc., and I try to stick to the basic rules as much as I can. But when I have to deviate from those patterns I want to do it in an artful way that makes it look believable, even though it is a layout that a condo would never have in reality.

My aim is always to create stages that have no dead spaces, stages where the space is full of clues and possibilities. I want to create such spaces and then breathe life into them. Of course that is not something that is done just with the set alone. It only reaches completion when the actors stand in that space and bring out its potential. - Even if the aim of making the fullest possible use of the stage space is the same, the taste involved in what you fill the space with must be different for the different theater companies that come to you for designs, isn’t it?

- Of course it is different. For example, the spaces three spaces I create for potudo-ru, Gring and Ashitazukan are completely different in my mind.

Potudo-ru is the company for which I have to pay the most attention to the details, so I use a lot of deforme. For example, if there is something in the set that has a shiny surface I will make that surface extremely shiny, or if there is a pock-marked concrete wall I will make it almost excessively pock-marked and if something is going to be dirty I will accentuate the dirtiness. It will look “real” but I also use a sense of deforme to make it something that could never really exist.

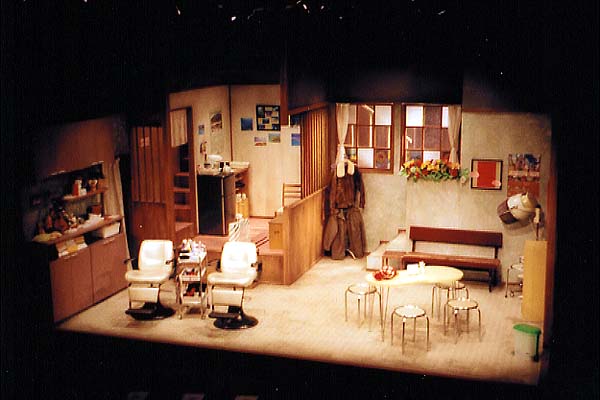

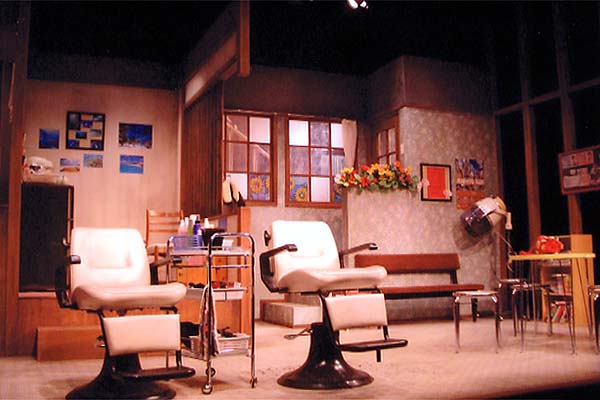

In contrast, the Ashitazukan company does the most natural dramas (although this may be a misleading expression) of any company I work with, so I want to create a more conventional sense of realism for their stages. For example, I don’t want too much white wall space because I want the room to have a sense of actually having been lived in. If I use too much deforme I will destroy the naturalness of the world they want to create on stage. So, I want to create spaces that are closest to actual daily life. Akihiro Makita’s works deal with people’s animosity and with those disagreeable but somehow endearing negative aspects of people, so there is no need to make the stage spaces unnecessarily bizarre or unnecessarily bright. So, I want to give a feeling of nonchalance to the spaces.

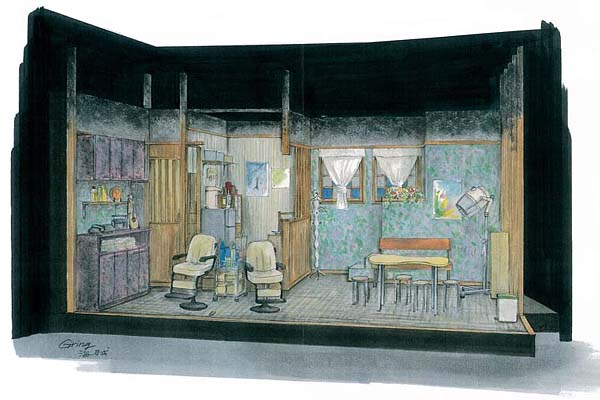

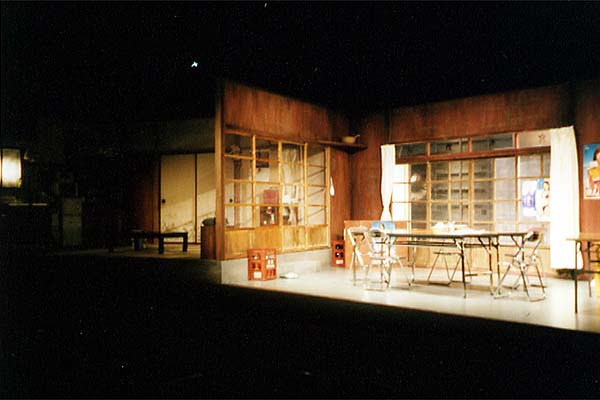

With Gring, I make stage plans that are more abstract than with the other two companies. I don’t want to fill up the space with hard-set forms but to leave spaces where breezes can drift through naturally. The company’s writer and director, Go Aoki, starts talking about a work before it is completely written. What is interesting is that he decides what characters/actors will be in the play and then writes the script while thinking about how he will bring each character in and out of the play. Each day he comes in before everyone and makes correction from the previous day and adds the next section. At the start there is only a rough outline, then as the script begins to take form the items of the set that will be necessary for the actors actions are added. Of course the demands are different for each work and it is difficult to make generalizations, but Aoki-san is the kind of writer for whom the elements of dramatic distance, such as conversation between characters across a table, and the positions on the stage become very important. I want to use my stage design to help Aoki-san create the world he is seeking.

I don’t really know what people are expecting when they ask me to do a stage design, but I certainly want to create something that will help communicate that concepts and messages that each of the directors have. That is what I believe my job to be. - You are now working with many important young writers and directors. From your perspective in stage art, what do you see as the main trends in Japan’s small-theater scene today?

- With regard to the companies that come to me for stage designs, there definitely seem to be a lot of requests for daily-life spaces, like rooms of the condominiums and apartments people life in. I used to think simply that it was because writing about those types of situations was easier for the playwrights, but recently I feel that it may be because people need a place of their own in order to express themselves. Perhaps, to some extent, in order to act they need a place with a lot of clues that tell them this is their space, a space where they belong. And there are also times when I want to say, “Why don’t you try acting in a more abstract space?”

When I was doing theater with our circle in college we practiced with a lot of physical movement, but today I don’t see many companies that begin rehearsals with voice exercises and running physical training anymore. It may be that I am just not there at the right to see those kinds of exercises, but I also notice that they will use microphones on small-theater stages now. I guess it is because they simply choose to use microphones rather than building up a stage voice. - Is it that actors have a reluctance to developing the kind of stage voice that is out of place in normal life? In the past people thought that it was that very difference from normal life that was the attraction of small-theater drama.

- I used to feel that way, too, but now I find myself accepting these plays based on the everyday with almost no resistance at all. (laughs)

- The plays are introspective, the greatest focus of interest is human interaction and relations and people are really only interested in themselves ….

- Yes, perhaps. We may be living in a time where expressing yourself is the biggest form of social protest or problem-raising that people engage in.

Toshie Tanaka

What reveals the meaning behind the stages in the form of everyday apartment rooms?

Interview with stage designer Toshie Tanaka

Toshie Tanaka

Raised in Gunma Pref. In 1974, Toshie Tanaka entered the drama and theatre arts course of Meiji University in 1993. After participating in the drama club of Gunma Prefectural Maebashi Women’s High School, she was active in the “Katsugeki Kobo” theater club of Meiji University for two years. Having had a love of painting since childhood, Tanaka began working on stage art and set design along with acting. She continued activities with the university theater company “Doubutsu Denki” and her own theater unit until graduation and after graduation completed the correspondence course in Design from the Craft and Industrial Design Dept. of the Musashino Art Jr. College. In 1997 she did the stage design for the second production of the company potodo-ru titled Uramimasu, which started Tanaka on her self-taught career in stage design. Today, her services as a stage art designer and planner are in high demand as she handles about 30 productions a year primarily in the small theater genre.

Interviewer: Eiko Tsuboike

Stage art of 2nd potudo-ru production Uramimasu

Premiere: 1997 at Waseda Drama Kan

Written and directed by Daisuke Miura

Planning/Production: potudo-ru

Tanaka’s first professional stage design for potudo-ru’s early time’s representative work.It’s a family drama like soap opera.

Stage art of 12th potudo-ru production ANIMAL

Premiere: 2004 at Mitaka City Arts Center

Written and directed by Daisuke Miura

Planning/Production: potudo-ru

This is the first “outdoor” set used by potudo-ru.

It is the hang-out of the “teamers” under a railway bridge over a river. Notice the authenticity of the graffiti.

[Stage size] proscenium: 10.8m(W)×11.0m(D)×6m(H)

Photo: Wakana Hikino

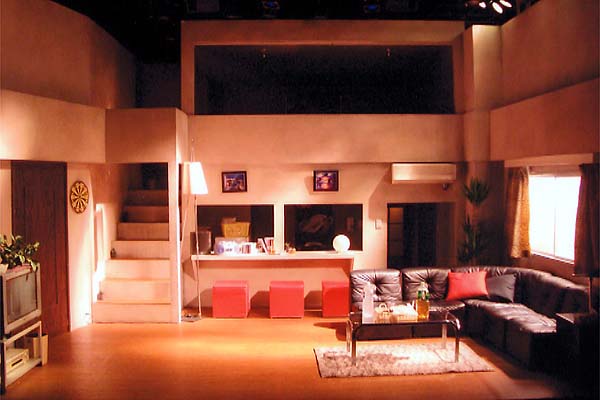

There is a stairway leading up to the loft and a door beside it that opens to a shower room, which barely visible from the audience.

The theme of this play is sexual desire. The room in the morning after the night’s events.

Stage art of 13th potudo-ru production Ai no Uzu

Premiere: 2005 at Shinjuku THEATER/TOPS

Written and directed by Daisuke Miura

Planning/Production: potudo-ru

This stage is designed to represent a singles club in an expensive condominium. The loft to the rear is the play room.

Below that at the back of the client waiting room is the staff area behind a counter.

[Stage size] movable box style: 5.75m(W)×5.95m(D)×3.95m(H)

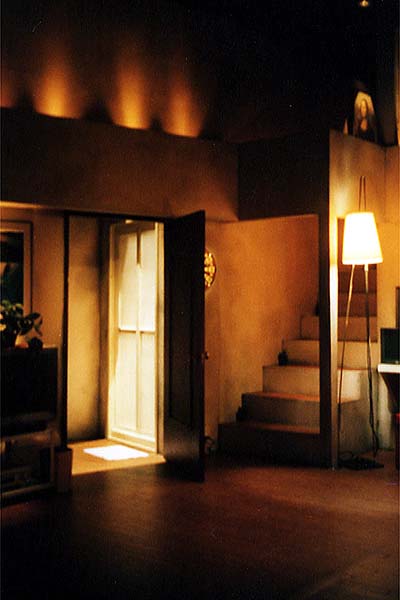

The veranda of a one-room apartment.

The design is done in fine detail that includes the color of the outside wall and even its texture.

The messy interior of the room.

It is the kind of room that today’s young people gather in to have sex, watch television, play video games, take baths, eat meals, etc.

Photo: Wakana Hikino

Photo: Wakana Hikino

The interior of the bathroom on the back wall of the room.

Photo: Wakana Hikino

14th potudo-ru production Yume no Shiro

Premiere: 2006 at Shinjuku THEATER/TOPS

Written and directed by Daisuke Miura

Planning/Production: potudo-ru

√

A rough sketch for the set of the play Pirates.

Stage art of 12th Gring production Pirates

Premiere: 2005 at The Suzunari

Written and directed by Go Aoki

Planning/Production: Gring

[Stage size] movable box style: 6.96m(W)×6.27m(D)×4.15m(H)

Stage art of Hamabe no Kame to Kurage (Turtles and Jellyfish on the Beach)

Premiere: 2006 at Shinjuku THEATER/TOPS

Written and directed by Akihiro Makita

Planning/Production: Ashitazukan

[Stage size] movable box style: 5.75m(W)×5.95m(D)×3.95m(H)

The left stage living room is connected to the right stage an election campaign office, which used to be a Japanese-style pub and is now renovated.

Stage art of Ranman!

Premiere: 2005 at Mitaka City Arts Center

Written and directed by Akihiro Makita

Planning/Production: Ashitazukan

[Stage size] proscenium: 10.8m(W)×11.0m(D)×6m(H)

Related Tags