- We would like to begin by asking about NDA, which celebrates its 10th anniversary this year.

- The acronym NDA stands for “New Dance for Asia,” and it is an international platform that invites and introduces primarily talented young Asian choreographers and dancers. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic it was held in December last year for the first time, but normally it has been held in August. Presently, we have partnerships with seven festivals in Asia and Europe (*). In this partnership, the directors from each country attend the seven festivals and select outstanding works to invite to their own festivals in a mutual performance exchange system.

*The seven festivals partnered with:

・Japan “Baku Ishii & Tatsumi Hijikata Memorial, International Dance Festival ODORU-Akita (Dancing Akita)

・Singapore: “cont-act Contemporary Dance Festival” (formerly M1 CONTACT)

・Hong Kong: “H.D.X. (Hong Kong Dance Exchange) International Festival”

・Macau: “CDE (Macau Contemporary Dance & Exchange Springboard)”

・ Laos: “FMK (Fang Mae Khong International Dance Festival)”

・Taiwan: “Stray Birds Dance Platform”

・Spain: “Masdanza”

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, our festival’s activities in 2020 were limited to posting filmed works of young choreographers in Korea online, but in 2021 we resumed actual live gatherings and exchanges. Films were taken of the performances by 11 Korean companies/groups (performed in front of audiences) in Seoul and sent to our partner festival directors, and agreements have been made for four of them to be invited to the other festivals. This year (2022), we expect to be able to invite the other festivals’ directors to Korea for true (in-person live) international exchange again. - What kind of programs does the festival have?

- It changes bit by bit each year. At first, the festival had a different name (Gwang Jin International Summer Dance Festival), but along the way we re-thought the festival concept. Just after we changed its name to NDA, in 2016 we had the following types of programs taking place over the course of a week. In general, most of the choreographers taking part are in their 20s and 30s.

・International Company & Artists Platform

・Festival Exchange Program

・Asian Solo & Duo Challenge for Masdanza

・Asia Young Generations Stage

・Korea Choreographers Night

・Dance Camp Platform in Korea - Your program “Asian Solo & Duo Challenge for Masdanza” is partnered with the Masdanza international dance festival in Spain. This festival has been affiliated with the Yokohama Dance Collection.

- This is a platform that enables winners to compete in the semifinals of the competition at Masdanza, and we held it for the first time in 2016. That time, Junpei Hamada (who won the French Embassy Prize for Young Choreographer at Yokohama Dance Collection in 2018) participated from Japan. Since we thought the program name was too long, we changed it to the Masdanza Selection from last year.

It is basically an open-call competition for new works. It is also open to dancers from outside of Korea 20 years of age or older who have experience giving performances. As judges for the competition we have the artistic director of Masdanza, Natalia Medina, the Korean critic and producer Jang Kwang-ryul, and you, Norikoshi-san, who serves as an official advisor for us at NDA. - By the way, we would also like you to tell us something about the type of audience you get at NDA.

- Our audience mainly consists of young artists. We also have dance professionals such as the artistic director of SIDance (Seoul International Dance Festival), Lee Jong-Ho, coming to see and support our festival every year, but we don’t get many of the senior professionals such as the executive people at the dance associations coming to see it. I believe that NDA is primarily valued by young dancers as a platform where they can see the activities of Korean and Asian artists of their same generation and learn about the trends of young Asian choreographers, and also as a platform where they can connect to the international scene.

Yu Hosik

Korean alternative dance platform

New Dance for Asia (NDA) celebrates its 10th year

Yu Hosik

In 2012, dancer and choreographer Yu Hosik founded New Dance for Asia (NDA) (formerly Gwang Jin International Summer Dance Festival) at the young age of 30, and this year marks the festival’s 10th anniversary. NDA is not a large festival, but in the Korean dance world that has developed largely through dance associations and universities, it holds a special place as a platform where independent dancers and young dancers from abroad can meet and have meaningful exchanges. Yu Hosik is the artistic director, and as a dancer he is famous enough to have been given one of the only two exemptions from military service that were given out to male dancers each year and is also active at the top level as a choreographer.

Interviewer: Takao Norikoshi (dance critic)

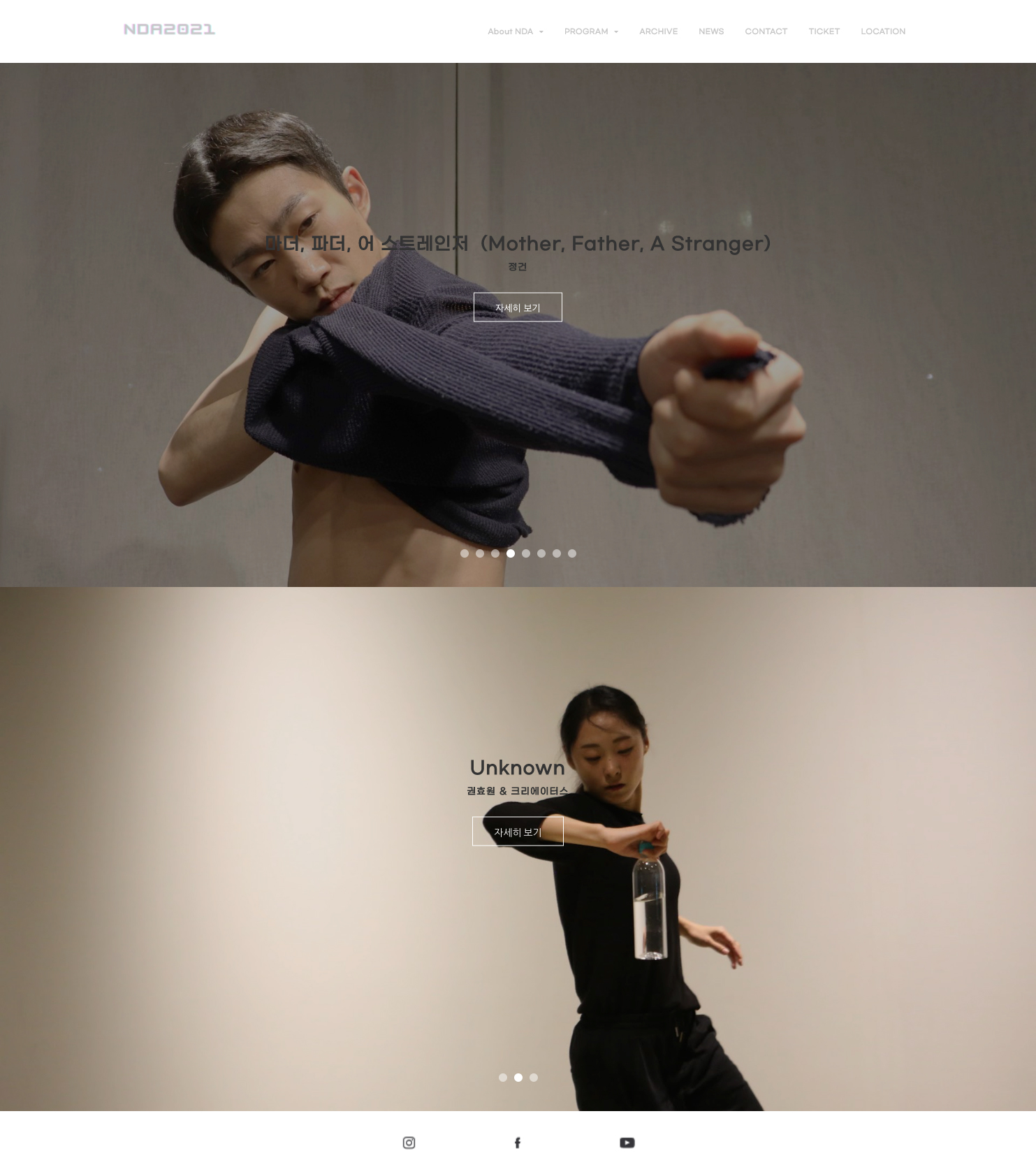

New Dance for Asia (NDA)

https://newdanceforasia.com/

- Next, would you tell us something about the history of NDA?

- We started the Gwang Jin International Summer Dance Festival (GSDF) in July of 2012 in the Gwang Jin District (Gwang Jin-gu) in the eastern part of Seoul. It was a small festival held in a small theater with seating for about 150.

- What led you to start GSDF?

- From 2008 to 2010, I was serving as a resident choreographer for Odyssey Dance Theatre in Singapore, for which I spent three weeks in residence there twice a year. The dance company there ran a large number of platforms, including of course a festival, and it also had many international exchange projects. At the time in Korea, there were almost no festivals that were run by dance companies, so we thought it would be good if we tried doing one.

- At the time, in Korea there were already some big festivals, in MODAFE (International Modern Dance Festival), in SPAF (Seoul Performing Arts Festival), and in SIDance (Seoul International Dance Festival). Didn’t you feel some insecurity about going into such a scene on your own?

- At the time, more than feelings of insecurity, I was motivated by a passion to do something. Because my aim was to start a small-scale but international platform, I felt I would be competing in a different realm from the big festivals that were competing for the big productions. So, I didn’t think they would be a threat to what I wanted to do. In fact, Korea had many festivals that were operated by the universities and the dance associations, and support grants were also given with a priority on them. So, there was a problem that the support didn’t reach the small works of young artists. At the time, ours was the only international festival for such independent artists.

- In terms of ticket sales, the dance associations and the universities also had an advantage in the scale of sales they could command, didn’t they?

- Yes, that is true. At the beginning, when we thought about ticket sales, we thought we had to program our festival with about 60% works by independent artists and about 30~40% works by university affiliated artists and dance companies. In fact, our tickets still often sold out. However, today our aim is understood widely and that results in a situation where we still have good audience draw with programs that are 80% to 90% works by independent artists.

- You were just 30 years old when you started your festival, so I’m sure you were a very unique presence in your position, in that you were very close to the active dancers you were dealing with, weren’t you? When I first heard that you were starting a festival, I thought of that as the kind of thing a wealthy person does as a hobby. And then, when I heard that you had sold your car to help finance it, I was surprised and impressed by the fact that you must be really serious about your endeavor.

- I started it with money I had saved through running a studio and giving private lessons, but when that still wasn’t enough, I did sell one of my two cars. At the time, I couldn’t even apply for a grant, because the requirement was that grants were only open to festivals that had been running for at least three years. Eventually, it wasn’t until our sixth holding that we finally got any grant money, but after that we got large grants from the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture (SFAC) and the Korea Foundation Arts and Culture.

- The word International was included in the original GSDF name, but did you actually have any performances that you invited from abroad?

- At the time, we had an exchange with the Fukuoka Dance Fringe Festival, and we invited one team from them every year. In addition, there was a German choreographer that I had previously worked with before, but the rest were all Korean domestic teams.

After we entered our third year, when I was bothered by the weakness of our identity as that kind of an festival, I consulted with you, and you advised me that rather than thinking only about Korea, it might be a good idea to aim to be a festival that provided chances for young artists from around Asia to participate in.

Considering that, I thought it would be best to think of a new name for the festival, and the proposal I got was a name that didn’t have the words “Korea” or “Seoul” in it, and that was “New Dance for Asia” (NDA). - For you and for young artists as well, rather than tiring yourselves out trying to deal with the domestic power games, isn’t it more enjoyable to meet a variety of people from abroad and build a network with them?

- That’s right. After changing the name to NDA and building partnerships with countries like Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau, and Spain, we came to be widely recognized as a festival that had the advantage of providing chances for exchanges with overseas countries. Now there are other festivals in Korea and abroad that are copying our style of orientation.

- Can we ask you now about the accomplishments of NDA until now and the changes it has gone through?

- Although we seldom have opportunities to site their accomplishments, two important figures would be Kim Bongsu and Choi Myung Hyun. Both of them expanded their field of activities overseas after appearing in NDA, and that enabled them to reach a new level. Kim Bongsu, who is presently active in one of Belgium’s leading dance companies, Peeping Tom, has established the company named Mover with Kim Seol-jin that is now the center of a lot of attention.

- Peeping Tom has performed numerous times in Japan. And Kim Seol-jin is very famous as a dancer with an extremely flexible body.

- That’s right. And Choi Myung Hyun also achieved increased connections overseas in places like Singapore, and he has his own company that is quite popular and has now celebrated its 10th Anniversary Performance.

Before COVID-19, Goblin Party performed the two-part work Landing Error at NDA. They are a company that is popular around the world and would not normally be performing at a small festival like NDA, but it was actually them that came to us saying that they wanted to perform in our festival. And after their performance, Landing Error was invited to four of our partner festivals in Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau and Laos. Unfortunately, the performances had to be postponed because of the pandemic, but they will eventually be held.

From GSDF to NDA

- Next, I would like to ask you about your personal background. What got you started with dance originally?

- When I was in middle school, I used to copy the dance routines of popular “idle” groups and my mother encouraged be to pursue dance, so I started learning modern dance when I was in my second year of middle school. With ballet, you have to start when you are very young, but in Korea, most males don’t start modern dance until they are in middle school or high school. Then, those who want to pursue dance seriously go to an arts-oriented high school or university. In my case, I went to Kyeongbuk Art High School in Daegu. In schools, dance is divided into ballet, traditional Korean dance and contemporary dance.

- At that time, what kind of dance were you doing?

- From middle school until my second year at university it was centered around Martha Graham’s technique. It wasn’t very interesting to me and I didn’t do well in terms of grades, and several times I tried to quit. I also studied other techniques like those of Jose Limon and Trinity Laban, but the schools mainly encouraged the study of Martha Graham technique. In Japan, today’s dance is divided into modern dance and contemporary dance, but in Korea modern dance and contemporary dance are seen as the same thing, and there is little tendency to separate the two.

- If you were originally fond of idle type dancing, Martha Graham’s technique is quite different, isn’t it (laughs)? How did you first come to encounter contemporary dance?

- Kim Sung-yong was a lecturer at Hanyang University in Seoul where I went, and because he had been studying in France for a long time, I learned a lot from him. Today, Kim Sung-yong is the artistic director of the Daegu City Dance Company. This is the only contemporary dance company in Korea that has dancers employed full-time. There are always 35 to 40 dancers that belong to the company and receive a salary every month. In Korea there is also the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company (KNCDC) but it doesn’t employ dancers full-time. Instead they employ dancers separately for each project. The artistic director before Kim Sung-yong was Hong Sung-yop.

- Hong Sung-yop was the first artistic director of KNCDC, right? About 15 years ago I saw a program of his works, which had unique movement and direction, as well as humor, and I thought it was very interesting. He was a real star in Korea, wasn’t he?

- He is one who all at once raised the level of Korean contemporary dance stages. It was his works that everyone of my generation watched and learned from.

Another master that I learned from was Choi Du Hyuk. He danced the role of Christ for Yuk Wan Soon’s (a pioneer who was first to introduce the modern dance of the United States to Korea) masterpiece Jesus Christ Superstar. - All Korean men have the obligation to serve in the military. We are told that only a few who have special talents in some area can receive exemption from the military duty, and for young dancers in their 20s, having to spend two years in the military is something that they really want to avoid if possible, isn’t it?

- That’s right. Today, if you can finish in the top two in one of the three categories (ballet, contemporary dance, and traditional Korean dance) in the Seoul International Dance Competition or the Korea International Contemporary Dance Competition organized by the Korean Dance Association, you can get that exemption. But in my day, in order to get exemption, you had to win first place in either the National Newcomer Dance Competition organized by the Korean Dance Association or the Dong-A Dance Competition organized by The Dong-a Ilbo (East Asia Daily).

- So that means that in your day there were only two dancers a year who could get an exemption from military service, right?

- Yes. I won the National Newcomer Dance Competition. At the time, I studied at Hanyang University, and it had the most men who were able to get military service exemption of any university. I danced a piece that I had choreographed myself, but more important than the choreography itself was the appeal of the technique involved in how well the dance could convey a concept in the space of five minutes.

When a man gets to the age of 30, he automatically has to go into the military, so the point is to get the exemption before that age. I was able to win exemption in my seventh try, but it was really difficult because there were new talents coming up each year and my upperclassmen also remained in competition. - You got your exemption from military service in 2006, and from 2008 you served as house choreographer at the company in Singapore for two years. And in 2009, the piece heavy circulation you entered in the Seoul International Choreography Festival (SCF) won the Fukuoka Dance Fringe Festival Award and you were invited to Japan to perform it. It was a work that combined sharp timing and fine nuance, wasn’t it?

- In 2007, it was a work that won the best choreographer award for young choreographers organized by the Korean Dance Association. The fact is that during the SCF I had a broken wrist, so I had one of my underclassmen dance it for me. But in Fukuoka, I danced it myself.

- With such a record of awards、why was it that you didn’t become an association-affiliated dancer?

- Having seen at first hand with my professors at university and with the upper-classmen and under-classmen I was doing creation with how much politics were at play in that world, I decided it didn’t suit me.

A big win and getting exemption from military service

Yu Hosik wake up (in Dance Bridge International)

(Nov. 2014 at Kagura-zaka Session House)

- When you were invited to perform in Japan, it was a time when the Fukuoka Dance Fringe Festival had just begun, and things were rather hand-made. And due to the lack of selection, things were really a mixture of the good and bad. Coming from Korea where things were generally on a higher technical level, it must have surprised you.

- It was like a breath of fresh air (laughs). The existing festivals that I had come to know usually had three or four performances beginning at 7:00 or 8:00 in the evening, and that ended the day’s schedule. But at the Fukuoka Dance Fringe Festival there were about 50 performances, starting at 12:00 noon and lasting until 9:00 at night! The audience would come and go freely to see the performances they were interested in, and then go out and have tea before coming back again. It felt like being in a gallery, and I thought that was a great idea.

After returning to Korea, I was proud to be able to say that at the Fukuoka Dance Fringe Festival you can watch performances from 12:00 noon. Of course, due to budget restrictions there were some things that were lacking, but since it was a fringe festival, I thought it would be a good one for our [NDA] concept of exchanging opportunities with. - You also served as an advisor for the Hokkaido Dance Project (HDP) from 2015 to 2018. So, you have seen a lot of Japanese dancers.

- HDP was also unique. The first half was a recital for the local dance studio(s) and the second half was the contemporary dance competition. That was a good way to gather audience. The approximately 1,500 seating capacity of the local public hall was filled by audience, which surprised me. Some of the competition participant from parts of Hokkaido outside of Sapporo even flew in by plane. Many of the works were amateurish, but there were also some good ones that we invited to our NDA festival.

Another unique aspect was that what we gave were not “reviews” but “advice.” After watching three performances, we were asked to make comments in front of the audience. At first that was new to me, and I had some difficulty getting used to it. - That is a method proposed by the artistic director, Kenji Hirose. Hearing such comments about the performances they have just watched encourages the audience to think about the works they are seeing. Also, with the dancers you had chosen to invite to NDA, we had them join us as “guests” and the three of us (you, myself and the guest) would talk, and I was very interested in your comments, because like most Korean dancers, you learn and teach dance at the university level, which brings a theoretical logic to your comments.

- That was good, I thought. And I also received a lot of inspiration from the unique festivals like that I saw in Japan.

- You have been involved with many Japanese dancers, including through the “ODORU-Akita” Festival that NDA has a partnership with. Is there any advice you would like to give Japanese dancers in general?

- I was only able to attend “ODORU-Akita” twice before the COVID-19 pandemic, but I liked the way they varied their programs with flexibility between the years for competition, the years for invited performances.

As for advice that I would offer Japanese dancers, I like the great diversity of ideas they bring to their works and the open appeals of them, but on the other hand, I also get the impression that more attention could be paid to way the ideas are realized in the works. And I also feel that they are not concerned very much with the details of their movements. In contrast, Korean dancers are good at the physical aspects of movement and technique, but their work lacks diversity in terms of ideas, such as the fact that duo works are almost always emphasizing contact. - When I go to overseas festivals recently, the activities of Korean and Chinese dancers are impressive, and I believe there is a consensus that the Asian dancers are strong in terms of technique. But then, when people at these festivals see Japanese dancers with their main concern on the character they project, people’s reaction often seems to be, “Wait, what is this?”

- Korean dancers have mainly worked their way through elite dance courses, so it is true that most of them have a solid technical foundation. But, in terms of their ways of thinking and the mind they bring to their dance, the educational process they have been through has in many cases had a restricting effect on these mental aspects.

Of the Japanese choreographers I have seen, I think Nobuyoshi Asai-san is especially good. He is not bad technically as well, and his work reflects clear concepts and expressive capability. He started out from street dance and then went on to Butoh (Sankai Juku), so even though he has not been through what we would consider an elite course of dance studies, he is able to choreograph works base on a sound foundation in contemporary thought. Reisa Shimojima-san, leader of the KEDAGORO company, is another who may be lacking in many aspects of basic dance technique, but she has a clear grasp of her own methods of expression, and she wins recognition in any country she goes to perform in.

About Japanese Dance

- Next I would like to ask you to tell us something about the changes you have seen in the dance environment in Korea during your ten years of NDA activities.

- There were changes in two important organizations that support dance, the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture (SFAC) and Arts Council Korea (ARKO). First of all, there has been a big change in the organization of the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture beginning in 2022, when their grants for festivals have been eliminated and the operation of that function transferred to the City of Seoul. Instead, SFAC will focus on the works creation side and is increasing its programs in that direction.

Also, this year there was a presidential election, and since the Arts Council Korea is under the auspices of the national Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, there were fears about how things will change under the new administration. However, since from last year 90% of the grants from Arts Council Korea when to their own related organizations, there wouldn’t be much effect anyway. For that reason, many of the festivals are now joining together to form associations that will serve as the recipient for grants. For example, these will be something like the Seoul Section of the International Dance Council (CID-UNESCO) of SIDance. In any regard, however, things will be more difficult for independent festivals like us to carry on activities. - Aren’t independent artists getting together to form their own associations?

- In Korea, it has become popular for groups of seven or eight independent organizations to get together and form organizations similar to cooperative unions. However, as long as there is money involved, there is always the fear that, regardless of how high their ideals may be at first, in the end there will be factions and power structure involved, just like with the associations. I don’t think that type of system is realistic for the arts in a democratic society, so I have no inclination to take part in that type of movement.

- It is true that an “Independent Artist Association” was formed in Israel, but it eventually dissolved. How about the state of support for the young artists in Korea?

- There is a lot of support for creative activities for young artists. Compared to the size of the dance population, there are a lot of educational programs, and there are many opportunities to present works. In this regard, I think Korea is one of the top classes in terms of this kind of support in the world. The big festivals like MODAFE sponsored by associations are recently providing more opportunities for independent artists. For this reason, there are more and more high-level works being created by freelance artists and independent dance companies.

- What is the process for receiving such support?

- The usual process involves first a screening of written documents explaining the project plan by the artists. The second stage is appearances at showcases or video presentations. And the third stage is interviews with the artists.

- Has there been any kind of support for young artists regarding the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic?

- There have been quite thorough anti-pandemic measures. The Republic of Korean Dance Association (former “Korean Dance Association”) took measures to see that support finances were distributed via foundations in each region of the country. As a result, for five months each in the first and second fiscal periods up to five members of independent companies were given monthly support of roughly 180,000 yen (approx. 1,440 USD). Furthermore, financial support for creative activities was also supplied separately. Also, for dance studios and theaters, support for personnel wages and operating expenses were given out.

- How about the support system for producers?

- In the past, there wasn’t enough support for them, and producers tended to be thought of as the people who wrote requests for grants for the artists, but now there are separate support grants for producers as well, which has clarified the original roles producers play. There are now famous freelance producers whose networks have expanded beyond Asia and extend to the Americas and Europe, like Park Shin Hye and Lee Mijin, who has been producer for two very popular stars worldwide, namely Kim Jae Duk of Modern Table and Kim Bora of Art Project BORA.

- How about the support for dramaturgs?

- It differs by individual depending on how they are involved in a production, but the support is increasing. And since grants include financing for production staff support, there is no problem with dramaturgs participating in productions.

- Are genres like street dance and modern circus connected with contemporary dance?

- Not as much as they should be. Circus is performed in collaboration with theater companies mainly involved in physical type performance. Until last year, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture was providing comprehensive support for circus and contemporary dance, but from this year the two are supported separately. Modern Circus is becoming more actively pursued now around Asia too, but there still aren’t any performers with the kind of impact that someone like Hisashi Watanabe has.

- Thanks to the high degree of support for dance in Korea, many young artists are creating good quality works, aren’t there? For that reason, it seems that there is a need for platforms like NDA to introduce them on the international stage.

- Yes. In the area of international exchange, Korea has a variety of foundations that will cover artists’ transportation costs to go overseas. For that reason, from now on there will be a need not merely for introducing good artists, but it will be important for there to be platforms like ours that have unique visions and networks that provide the artists with meaningful exchange opportunities.

Dramatic changes in the Korean dance scene

- My I ask your thoughts about how you want to see NDA develop in the future?

- For the last two years or so we have divided our program so that we have two parts conducted in Seoul and one in Daegu. This year we plan to experiment with having all the parts of our program, conducted in Daegu alone. This is because Daegu is the city that is second only to Seoul in terms of infrastructure, and it also has the second largest dance population, with many active young artists, and I feel a great potential there.

So, rather than competing with all of the other festivals in Seoul, I think it can probably be better for us to build a unique program in Daegu. There is the international airport in Daegu, so we can travel directly back and forth to Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and Japan, so traveling will be easy too. Of course, we will also maintain our contacts in Seoul, so that we can invite choreographers from Seoul to come and do workshops and create works in Daegu. - Will you be receiving any support from the city of Daegu?

- The Daegu Cultural Foundation doesn’t have a system for supporting festivals, but since there is support for international exchange, we are applying for support through that framework.

However, although Daegu has many dance performances, 95% of them are free of charge for admission. Most cities in Korea besides Seoul are that way. Even for the Daegu Contemporary Dance Company I mentioned earlier, their tickets for performances are about 10,000 won (about 1,000 yen. Or about 8 USD). This is thanks to the solid public support, but I still think that in order to raise the quality of the artists and their works, there is a need to increase the number of paid performances that people truly want to see and will be willing to pay the price to go to. - Listening to what you have just said, it sounds as if the level of the Daegu Contemporary Dance Company’s performances is quite high. Is there any possibility that NDA can work together with them?

- It’s possible to invite the Daegu Contemporary Dance Company to NDA, but we don’t because their works don’t fit our concept. Their current artistic director Kim Sung-yong’s term ends this December, so it may be possible to work together with him after that.

By the way, I choreographed a solo work for a female dancer of Daegu Contemporary Dance Company that is scheduled to be performed in April. It will be performed as a production of the dance company I lead, Designare Movement, which is also the organizer of the NDA. - So, Designare Movement, where the managing office of NDA is located, is actually a dance company?

- Yes. Although it is called a dance company, it doesn’t have any full-time affiliated dancers, but gathers dancers anew for each production. In fact, I just created another group in 2021 named PYDANCE, which is made up of young dancers from around Daegu. I started the group in order to be able to do creative work with young people who have a broad perspective. In October, we will present two days of performances under the title “Daegu Dance Ground.”

- Does this mean that you are presently managing a number of companies and festivals?

- That’s right. Designare Movement will hold NDA in August, and PYDANCE will hold “Daegu Dance Ground” in October. In PYDANCE, my role is as an advisor to young dancers, and we have performances planned in Poland in June and Mexico in August.

The infrastructure in Daegu is well-equipped and the support system is also good, but it is an area where the attitude towards dance tends to be rather conservative and it is also weak in terms of the amount of international exchange. - You talked earlier about the importance of the uniqueness of NDA. But the fact is that larger festivals also focus on international exchange and the subsidies for the independent festivals are decreasing. What do you want to do to develop NDA going forward?

- In order to answer that question, I think I should tell you something about the surprising discovery I had when I went to the Fang Mae Khong International Dance Festival in Laos.

The festival’s artistic director, Ole Khamchanla, is a dancer who is based in Lyon, France, but he still manages to hold the festival every year in Laos. It has been three years since NDA formed an official partnership with the Fang Mae Khong festival, but I still can’t forget how inspired I was the first time I went to their festival.

Until then I had only seen festivals that had fine theater facilities with everything needed for performances and specialized staff members. However, the festival in Laos had no infrastructure or theater, yet they were holding a festival that just showed the dance as it was.

They just had an empty lot in a residential area that they were lent free of charge, and there they piled up walls of concrete blocks to make a black-box theater, including a handmade office and shower room. For the performances they made benches to seat about 100. And the dancers themselves served in the roles of stage director and theater staff.

I don’t think they got any financial support in the form of grants for the festival, and the artistic director Ole Khamchanla brought European artists from Lyon every time. Nonetheless, the quality of the works performed was very high, and the attitude among all of the participants was very friendly, with everyone going out together to eat the local food and have a wonderful time engaged in open-minded exchange.

As you say, in Korea the money moves mainly with the associations and the amount of support fund finding its way to us independent organizations is decreasing. However, I find a lot of hope for NDA’s future when I look at what the FMK has done in Laos. - Until now, to some degree festivals in Asia have been based on the European model of associations using large budgets to organize large festivals and make opportunities for the artists. However, from now on, as NDA has done, festivals created by young artists as artistic directors may connect with other similar festivals to create a sort of underground network. And because they are small, the bonds these festivals build may be especially strong. So, I think that in this we can find big expectations for a new kind of networked festivals that fit the conditions in Asia, can’t we?

- That said, however, when we survey Asian festivals, I feel that the aspiration to become like European festivals still remains stronger than the desire to collaborate with other Asian festivals. When asked by a Korean critic why I felt the need to support the people in other Asian countries, I in turn asked how much they know about the contemporary dance in Asia?

Said in another way, I think there is still a lot that Asians can learn about the true appeal of Asian dance. In that sense, I am sure that is an area where NDA’s meaning of its existence is going to continue to grow. - To achieve that, are there any specific programs that you have in mind?

- Since we have a 10-year foundation in international exchange with the existing partners, from now on I want to do new programs deriving from our international exchange experiences until now, such as a residency program and collaborations by choreographers from Singapore, Japan and Korea.

Until a few years ago we were doing an Asia residence tour project named “Dance Cosmopolitan.” It was a project in which dancers from Thailand, Korea and Japan visited each other’s countries and created works to perform at NDA. In that project, the residencies were fun, but I felt that we needed to think more about how to make the creative process more efficient.

When we did the residencies in Korea or Japan, the costs were high, but in Laos it could be done for 1/4th the cost. So, I am thinking about doing a longer residency in Laos and then showing the work created there at NDA and the festivals in our other partner countries. Already we did a trail project in which Lee Kyung Gu of Goblin Party stayed in Laos and created a work with dancers of the local Fanglao Dance Company that was performed in Laos and at NDA, so I think there is a strong possibility of this being workable. - That means that you see the possibility for cross-border tie-ups that create programs to bring countries across Asia together. Yes. Of course, the local differences of the regions of Asia are stronger than in Europe, so it will probably take time to get used to the process. But I think that if we use residencies that take us back and forth between the localities to create dance works, I believe the kind of cross-border tie-ups you talk of will be possible.

NDA’s outlook going forward

Related Tags