- Because of your activities in a variety of fields and roles, it is difficult to know how to introduce you.

- My main profession after becoming an employee of the Korea Herald in 1977 was always that of a newspaper journalist, but I ended my more than three decades as a journalist when I quit the Yonhap News Agency in March, 2009. So now I am involved purely in the field of dance as a dance critic, chairman of the CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter and artistic director of Seoul International Dance Festival (SIDance).

- What was your initial encounter with dance?

-

I was interested in literatures, music, art and theater since I was a child and did things like writing poetry and publishing a school newspaper as well as going often to art exhibitions and concerts, but for some reason, dance remained the one thing I wasn’t interested in. As a student I remember being very bored by the performances of traditional Korean dance by a troupe from an arts high school. It was in the 1970s when everyone was interested in Western culture, and in that context dance in general appeared to be a third-rate genre not nearly as sophisticated as the other arts.

Then, in the early 1980s, the monthly dance magazine Chun asked me to do translations of critiques and essays about dance from American and French publications. At first I was doing it as translation but I gradually found the things written about dance to be very interesting, so I began going around to the different countries’ embassies in Seoul to read magazines and other materials about dance. Then I began to write articles based on the things I was reading, which turned out to be quite well received. Also, for my translations I had begun going to see dance performances.

At the time, dance critics didn’t really exist in Korea, so the job of reviewing dance performances was usually given to music critics. When I spoke with the publisher of the monthly Chum , Mr. Choi Dong-Wha, he told me that he had started doing dance critique from scratch because there was no one else to do it. He said that although there were professional theater and music critics there were none in the field of dance, so people of ability were needed to support the dance world as critics. I remember being very moved by his words, and that is what led me to take on the additional job of dance critic along with my responsibilities as a newspaper journalist. That is how I came to be involved with dance. - As a critic, how did you come to establish the CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter?

-

I guess it was my fate to become involved with dance. Originally there was an older woman, a dancer, who was making the preparations to found a CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter, but she passed away suddenly and I was asked to take over in her place. Considering the fact that my profession was first and foremost that of a newspaper journalist, I refused the offer on the basis that I was not the person for the job. But the other people who emerged as prospects were not completely trustworthy. So, I decided that even though it would be difficult I should accept the position of president. The Chapter was then officially launched in 1996.

Since the 1980s, the Korean dance scene has seen the emergence of exciting companies and highly original works. The number of critics specialized in dance has grown and the dance world here in Korea has become quite active and dynamic. Seeing these developments, I began to feel that I had to do more than just writing as a critic. I got the feeling that I wanted to work more directly on the scene and possibly help speed up the advancement of the Korean dance world in effective ways by becoming involved in the production of works and international exchange. - What kind of organization is the Korea Chapter?

-

CID (Conseil International de la Danse) was founded in 1973 as a non-profit NGO within the Paris offices of UNESCO, and today it has grown to include chapters in some 160 countries around the world. The purposes of the Korea Chapter are to maintain ongoing exchange with the chapters in these other countries to enable us to invite outstanding overseas dance to Korea and also to provide opportunities for works by Korean dancers to be performed overseas.

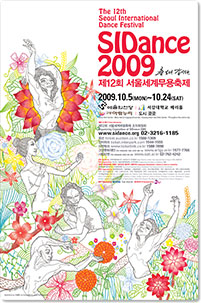

The main platform for these activities is our annual Seoul International Dance Festival (SIDance) held each autumn. In addition to SIDance we have organized the Korea-Japan Friendship Dance event in 2005 in cooperation with the Japan Foundation, which brought Japanese butoh and contemporary dance to the Korean audience, and in 2007 and 2008 we worked with South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade to organize an “Africa Arts Festival” and the “1st Arab Arts Festival.” In 2009 we worked with the Korea-Arab Society to organize our “2nd Arab Arts Festival.” These festivals are designed to deepen people’s understanding of the arts and culture of specific countries and regions of the world through dance.

Other regularly held events are our annual performances on the themes of “Korean Dance Meets World Music” and “The Shining Colors of Korean Dance,” and since 2003 we have organized a “Digital Dance Festival” focused on dance with the latest technology.

Of course, we also produce performances of foreign and domestic dance works and also produce collaborative productions with international and Korean artists. We also have academic programs and we exchange judges with dance contests around the world as some of our many other activities.

In 2003 we were accredited by the Korean government as and arts organization, which has made it possible for us to establish close working relationships with government agencies and the foreign embassies here in Korea. This, in turn, has helped lay the foundation for a wider range of exchange projects. - SIDance clearly seems to be a central part of the activities of your CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter. What was your purpose in launching this festival?

-

In order to make the impact of our newly formed CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter, we quickly applied to host CID’s biennial General Assembly. Since our Chapter had just opened, some were saying that it was too early for us to be hosting the Assembly, but I worked to convince the committee to let us host it, explaining to them how impatient Koreans are by nature. Those efforts paid off and we were able to host CID’s 13th General Assembly here in Seoul. I wanted to see us organize a world-class dance festival to accompany the holding of this big Assembly, and the result was our first SIDance festival.

As a journalist I gad spent three years as a foreign correspondent in Brussels from 1992 to ’94. During that time I had gone to a lot of different types of festivals around Europe and they made me envious. Up until that time I had been working to introduce foreign culture and arts to the Korean audience through articles and the film/video materials that I had been able to purchase in Korea. I thought SIDance would be a great opportunity to bring actual foreign performances to the stage in Korea for the first time. Also, at the time, the only Korean dance being introduced overseas were occasional performances of traditional or folk dance, whereas there were almost no opportunities for Korean contemporary dance to be performed abroad. And, in fact, there were Korean works at the time worthy of being performed internationally. I wanted SIDance to be a venue where people from overseas could see Korean contemporary dance.

At the time, the Korean dance world was isolated from the trends and movements in international dance. Korean dancers knew nothing about what foreign dancers were thinking, what kinds of works they were creating and what they were doing in terms of exchange. So, I wanted our festival to be an opportunity to get to know the international dance world. These were the two main objectives when we launched our first SIDance festival in 1998. What are your criteria for selecting works for SIDance? -

The dancers, companies and works a festival chooses to present are very important as elements that express the philosophy and directions of the festival and well as determining its identity.

As artistic director, I make selections based on the fundamentals of dance, namely the elements of the body (physical presence) and movement. It is not that we don’t invite works that are extremely conceptual or theatrical, but we do tend to avoid those directions. Personally, I am stubborn about some things, and just as we speak of music in terms of sound and paintings are in terms of color and line, I believe that dance should be spoken of mainly in terms of the body and movement. Recently there are many works that mix the different genre, but successful mixing is only possible when the artists have a solid foundation in the fundamentals of their arts. In order for outstanding crossover works or fusion works to be born, the elements from each genre must be of the very highest level. But today we see productions being turned out too easily without a solid foundation in either theater or dance, and the results are like third-class musicals. It is terrible to see. That is why, at least in our SIDance program I want to show works that are based in the beauty that is unique to dance and exhibit the unique fundamental elements and skills of dance. So, we choose works that meet this standard. Of course, because we are a festival we offer a broad-based program including some works that are theatrical or conceptual in nature as well as some non-dance type works, but the main body of our programming is works that show us the essence of dance and makes us think about the meaning and potential of dance.

The next element is the social relevance of dance. My perspective may be influenced partly by my personal background as a critic and journalist and the fact that I come to dance from the audience, but when I select works I think about the influence they have on society and the historical context from which it derives.

Lastly, because a festival is also an event, it is meaningless if it doesn’t attract a large number audience. That’s why it is also important to the program is made up of works that the audience wants to see and works that attract the curiosity of the audience.

So, probably because our programming is done from a variety of perspectives in this way, SIDance presents a relatively wide range of dance works. That includes not only contemporary dance but traditional dance and invitations for artists from other genre such as tango and flamenco that also involve the essence of dance and add color and audience appeal to our festival. - Can you tell us about the financial aspect and scale of SIDance?

-

The overall budget is in the range of 100 million won (approx. 77 million yen at current exchange rate) each year, and 40 to 50% of that comes from public sector funding, while the rest comes from corporate sponsors and ticket sales. To operate on a budget of this size, funding from corporations is very important, but it is difficult to get that funding because dance is generally not one of more popular genre in the arts and culture. Unlike the festivals organized by the public sector, such as the Seoul Performing Arts Festival and Gwacheon Hanmadang Festival, we are a private sector festival and that makes public organizations reluctant to provide funding when we ask for it. However, among the various festivals eligible for national funding, we have been recognized for the scale and quality of our festival and the weight of its contribution to the dance world. In 2005 we were designated an “Outstanding Festival” and in 2006 we won the designation of “Most Outstanding Festival,” which has helped us gradually win larger grants of government money. In South Korea we have evaluation system for public funding, and with each improvement in the evaluation rank, the grants increase by 10%. We also get assistance from government agencies of the countries whose artists we invite that helps pay for transportation to and from Korea.

The run of SIDance is around 20 days each year, during which we present a program of 10 to 20 works involving around 100 dancers. The total audience each year is about 12,000. - One of the big distinctions of the CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter is your international collaboration programs. What countries do you collaborate with on productions?

-

That may reflect my personal love of hybrid culture, such as the culture we see in towns on the Malacca Peninsula where Confucianism, Buddhism and Christianity coexist in a natural mix and towns where the bi-cultural descendents of Portuguese and Asian ethnics live, towns with architecture that shows a mixture of Spanish and native culture, the Black Christ sculptures of Brazil and Argentina, the Catholic Mass hymns sung in the indigenous languages, etc. I am interested in all of these hybrid products of culture born of native and foreign cultures, the traditional and the contemporary, East and West.

I feel that Koreans have long been lacking in their understanding and interest in the cultures of other countries. It seems to me that the Japanese have much more interest in foreign culture. I began the international collaboration programs out of a desire to encourage a greater interest in the culture of others and the belief that this requires more platforms for direct encounter and exchange. Also, since the collaborative works we produce can be performed in Seoul and in the partner country, these programs have the additional merit of expanding the performance opportunities and venues for the dancers involved.

Our first full-fledged collaborative projects were special commemorative performances to accompany the joint Korea-Japan holding of the football World Cup, which included a work titled Birds on Board choreographed by as the Hiroshi Koike for the Japanese dance Papa Tarahumara and Korean dancers and another titled Festival Day choreographed jointly by Kim Itoh and Ahn Song-Su. For the Korea-Japan Friendship Dance event in 2005 we not only invited the Japanese butoh company Dairakudakan but also produced Japan-Korea collaborative works including Caused by Economy choreographed by Kota Yamazaki a work titled Somewhere choreographed by Kim Young-Hee. I believe these projects achieved outstanding results. In addition to Japan, we have done collaborative projects with artists from some 20 countries, including the Netherlands, Singapore, Mexico, Canada, France and South Africa. These collaborations are done not only within the framework of SIDance but also as part of other projects organized by the CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter.

Since I became an executive council member of the Association of Asian Performing Arts Festival in 2004, we have been able to produce works in partnerships with festivals in numerous countries, such as the Singapore Arts Festival, Mexico’s Festival International Cervantino, Japan’s Yokohama Dance Collection R and France’s Montpellier Dance Festival, and these projects have resulted in performances in both Korea and the partner countries.

In 2007, we were chosen as the only private-sector organization to participate in the Cultural Partnership Initiative promoted by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of Korea, which enabled us to do collaborative productions with dancers from Asia and South America in 2007 and with dancers from Asia and Africa in 2008 and 2009.

The way these collaborative projects are actually conducted differ depending on the work, but there are cases where we invite foreign dancers to come to Korea and other cases where Korean dancers are sent abroad to work on them. The duration of the projects also vary. For our projects with Canada, Mexico and Japan we had participants work on creating the pieces for about a month in those localities, then the Korean dancers returned to Korea for a while before going abroad again a couple of weeks before the actual scheduled performances in those countries. Then everyone came to Korea for the performances here. These were two-country collaborations, but we have also experimented with multi-country projects in the Little Asia Dance Exchange Network program.

Even in the more active genre of theater and music, there are probably few organization that are undertaking such a variety of exchange projects with so many countries. These collaborations require a larger budget than simply inviting foreign works to Korea and they also involve more risk, because they are not works that have already won a reputation, but we still find them very rewarding to work on. What is the Cultural Partnership Initiative? -

It is a residence grant program created in 2005 as part of the Cultural Exchange Project aimed at cultural exchange with the countries of Asia. After that the scope was broadened to include South America and Africa. Unfortunately Japan is not included in the project. Perspective study residency candidates are solicited through 21 organizations in the fields of general culture (8), arts (6), culture industries (3), media (1), tourism (1) and sports (2). In the arts, the participant organizations include the, Korea Arts Management Service, the National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts, the National Folk Museum of Korea, the Arts Council Korea and the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea from the public sector and our CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter from the private sector.

The specifics of the residencies differ with the different organizations, but in our case we chose six people for six-month residencies and have them participate in multi-country workshops, creation of works and performances to gain experience in dance exchange and collaboration know-how. During the six-month residencies we also provide programs offering Korean language classes and Korean cultural experiences. Although only the support only covers the actual costs of residence and allowance for creating works, it is still an interesting and rewarding program. - What collaborations are you planning from 2010 onward?

- We had plans for collaborations with artists in Singapore, Italy, and Eastern Europe, but with the current economic downturn we have been forced to postpone them. We want to wait until the situation improves. The only project now set to be held under the Cultural Partnership Initiative for 2010 is one with Brazil. As for other countries, we haven’t decided whether do things again with Asia and Africa regions or just Asia, since we have done projects with Africa for the last two years in a row.

- You have contributed to Korean dance in many aspects. How do you view the Korea’s present dance scene?

-

I think it has finally freed itself from the academic establishment, the network of connections and the preconceptions about what creative dance should be like. In the past we often heard foreign critics say often that the Korean dance world is unable to free itself from academism. To some, academism may sound like a positive term, but what it meant in this case is that Korean dance was unable to go beyond student [college circle] dance. Because of the strict teacher-student relationship that dominated in the academic establishment of the dance world, even when independent choreographers created works, they would often be subject to review and revision by their professors. Lately the individual dancers are free of that influence and their creativity and choreographic skills have improved. As a result, they are now producing works worthy of being performed on the international stage. Of course, in the past there were always some people active on the international scene, but it is only recently that we have a large number of emerging artists capable of working on the international level.

I feel that we are finally beginning to see real reason for optimism in the Korean dance world. After the launching the SIDance festival in 1998 and beginning to build an international network, there were a number of years where there were still no works of Korean dance that we could send abroad with confidence. But now we are seeing the emergence of works and dancers that are worthy of the international stage.

Furthermore, the government is much more aware now of the serious need for internationalization and taking Korean culture abroad. In the past, government funding might be made available for overseas performances of traditional Korean dance, but never for contemporary dance. Recently, the consciousness is spreading among officials that when Korean dancers are invited to attend respected overseas festivals it is only natural that they be supported with public funding. At the end of October (2009), a “Korean Contemporary Dance Week” was organized jointly by the Korean Arts Support Center in Sao Paulo, Brazil and the City of Sao Paulo with five companies traveling from Korea to participate. This kind of event was unthinkable until quite recently. The realization of this event pleased me greatly, because it shows that the government now feels that international exchange through dance should be supported with funding from the government, whereas in the past participants in overseas exchange events in dance always had to pay their own way. Another thing that impressed me in Brazil was the fact that Korea has finally begun to follow the path of overseas performance projects to North America and South America pioneered by Japan a good number of years ago. - What trends do you see recently in dance?

- In the past there were trends taking place in the Korean dance world, but recently there are not movements that might be called trends. The Korean dance world has become much more diverse with the emergence of new talents in their 20s to early 40s. A highly diverse range of impressive choreographers representing a wide demographic, such as Lee Kyoung-Un, Shin Joung-Chol, Lee Tae-San, Chung Young-Do, Choi Hyok-Jin, Lee So-Na, Park Sung-Ho, Shin Chang-Bo and Cha Jin-Hyok are now working with great freedom and originality in genre ranging from physical dance and theatrical dance to technology-enriched dance.

- It has been two years now since South Korea’s administration change and there have been rapid changes in culture/arts policy and the system of support and grants for the arts. What are your thoughts on these developments?

- There have been proposals for a variety of revisions in the system, such as entrusting the allotment of grants to the local governments, putting the Arko Arts Theater and other public theaters in the Dae-hak Street area directly under the supervision of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and scaling down the activities that have been conducted until now by the Arts Council Korea, but currently these changes are in a state of flux, so I don’t want to make any comments about them at this point in time.

- How has the designation of the Arco Arts Theater as a facility specializing in dance influenced the Korean dance world?

-

I was very happy to see the Arco Arts Theater designated as a dance theater. For any genre of the arts to grow it needs its own specialized hardware and infrastructure, and that is something the dance community in Korea has not had until now. The dancers and choreographers active in the dance scene don’t have much capability or means to secure the necessary social conditions or environment by themselves. That is what we are very fortunate that the government has recognized the dance world and taken the initiative to build a theater for dance.

According to what I have heard, there are now plans in motion to group together the four Dae-hak Street area theaters—Arco Arts Theater, Arco City, Dongram Theater and Sansan-nanum Theater—together as the Daehakno Arts Theater to be managed by a new foundation to be launched a foundation in January 2010. It is still in the preparatory stage and the artistic director is not decided yet, so we don’t know what specific effect this move will have on the Korean dance world. - Thank you for taking time from your busy schedule for this interview.

Lee Jong-Ho

Leading South Korea’s dance world

CID-UNESCO Korean Chapter and SIDance

Lee Jong-Ho

Born 1953. Studied French Literature at Seoul National University and graduated from the university’s graduate school.

He worked as a correspondent for the French magazine Le pays du Matin Clalme (1977), as a journalist for the French weekly of the Korea Herald newspaper (1977-1978, 1979-1980), after which he transferred to the Yonhap News Agency in 1981 foreign, where he served in the foreign correspondence dept., Society Dept., foreign correspondent to Brussels, Culture Dept. chief, and senior culture editor before resigning from the company in March 2009.

He is recipient of the Ministry of Culture & Tourism Award (2007), the Korean Modern Dance Development Association’s International Exchange Development Award (2007) and the medallion of Chevalier dans l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres (2007).

He served as Executive Council Member of the Association of Asian Performing Arts Festival (2004-2008), as President of the Korean Society of Dance Critics (2001-2004), as a member of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s Performing Arts Advisory Committee (2004-2008), as a member of the planning committee for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s ASEAN Special Summit (2008-2009).

Presently he serves as President of the CID-UNESCO Korea Chapter and administrative chairman and artistic director of the SIDance festival.

SIDance (Seoul International Dance Festival)

TEL +82-2-3216-1185

FAX +82-2-3216-1187

http://sidance.org/

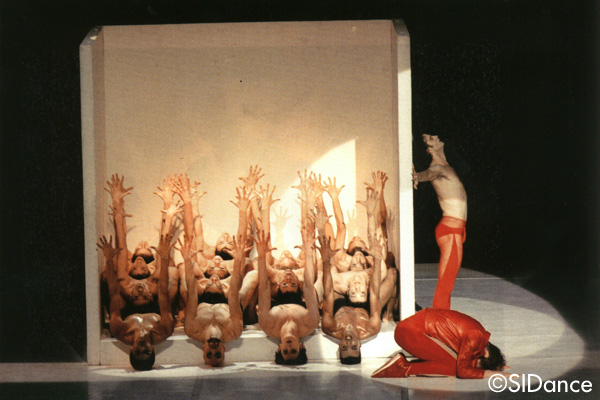

Maurice Bejart

Ballet for Life

(2001)

©SIDance

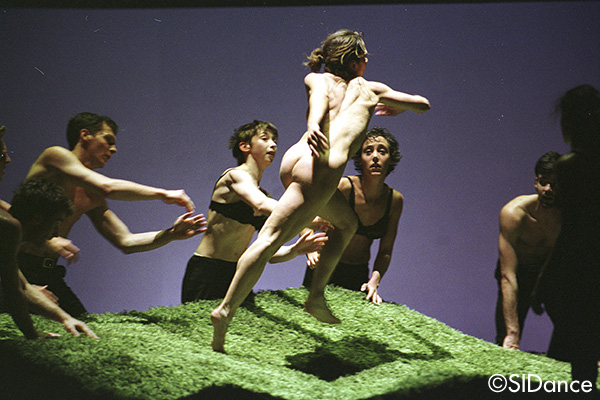

BALLET PRELJOCAJ The rite of spring (2003)

©SIDance

Akram Khan

ma (The earth)

(2004)

©SIDance

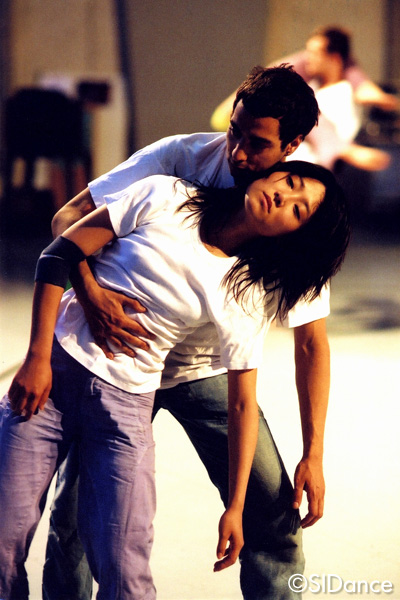

International collaborative performance with young dancers from Asia and Africa

©SIDance

Cultural Partnership Initiative

Related Tags