Culture Section and Public Relations Section

- How did your involvement with Israel begin?

-

While I was studying art in the graduate school of the Tokyo National University of the Arts I made a backpacking trip around the Middle East, visiting Turkey, Greece, Syria, Jordan, Egypt and Israel. After getting my degree I had planned to stay on as a member of the university faculty but I ended up marrying a man I had met in Israel on that trip. Although we ended up divorcing after about ten years [laughs] I had the desire to learn more about the culture of my husband’s country. It just happened that around that time there was an employment opening at the embassy and I got the job. Embassies in Japan range in size from the American Embassy with its hundreds of employees to places in one apartment with just the ambassador and a secretary or two. Among these, I believe the Israeli Embassy is medium-sized.

However, my job with the Embassy when I was first hired had nothing to do with culture, I was doing little more than just answering the phones. From there I moved to accounting and entered the political section. To begin with, at the time culture affairs were handled by the Public Relations Section. The Israeli Embassy didn’t establish a Cultural Affairs Section until 1994, four years after I began working there. It was a time of major change just after Prime Minister Rabin signed the peace agreement with Secretary General Arafat (1993 Oslo Accords, 1994 establishment of Palestinian National Authority). I was told that there was going to be peace now in the Middle East and cultural programs would become a new focus, and since I was educated at the Tokyo National University of the Arts I should head the new Cultural Affairs Section. So myself and an Israeli woman appointed as Cultural Affairs officer (the wife of an Embassy diplomat) started the Cultural Affairs Section from scratch, just the two of us.

But I had benefitted a lot from working in a number of departments at the Embassy in the four years before that. I had learned that just being informed on culture and the arts was not enough. To do the job well you had to know the important points for getting things done within the Embassy organization. - Was it smooth sailing from the beginning with the Cultural Affairs Section?

-

My superior when we started the section, Ms. Idit Amihai, was a person of exceptional capabilities, and I hear that now she is the head of the art exhibition department of the Bureau of Culture and Science in Israel. I learned a lot from her about operational skills and spirit.

In the year 1994 when the Cultural Affairs Section was launched we undertook a lot of new projects including a Dani Karavan exhibition, a concert tour by the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, contemporary art exhibitions, a film festival and a food fair. Our film festival was supported by the Japan Foundation and the Sasagawa Foundation (present Nippon Foundation). I believe our budget was about 30 million yen (approx. $390,000). That is a small budget for an embassy, but it was rather revolutionary for our Embassy, where it was difficult to even get a budget 10 million yen. From that beginning the Cultural Affairs Section gradually became an established presence capable of carrying on programs on an ongoing basis.

In that way we got off to a very good start. But soon after, Prime Minister Rabin was assassinated, and by another Israeli at that (Nov. 4, 1995) and the political situation rapidly deteriorated. Around the year 2000, terror attacks were occurring with increasing frequency and the so-called Second Intifada broke out among the Palestinians (Sept. 28, 2000), followed by the 9.11 terror attacks in the US in 2001. All of this contributed to a decline in culture and arts programs.

Since arts and culture programs can be considered a war of images, there is an aspect of them that is, of necessity, influenced greatly by public opinion. With 9.11 there was no direct connection between Al-Qaeda and Israel, the general connection with the Middle East problems caused Japanese sponsors to withdraw their support [for Israeli culture programs]. Even though it happened to be the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and Japan, all of our Cultural Affairs Section programs were cancelled. For a while we had to return all of the budget we had finally been able to get.

Later, with the second Lebanon War in 2006 and the air attacks on the Gaza Strip (2008), it was as if we were building sand castles promoting Israeli arts and culture only to have them washed away each time by the waves of war.

However, all our efforts were not for nothing. Even if the projects we undertook could not be realized, the personal relationships we built in the process have led to a small but growing number of partners who agree that the value of art and culture is not determined by politics. Those relationships of trust are now the foundation that our programs today are being built on. - At times of political tension do you get instructions from the government in Israel?

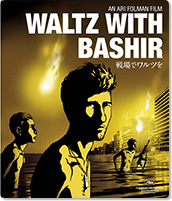

- At the Israeli Embassy, the Cultural Affairs Section and the Public Relations Section have different roles. The Public Relations Section is charged with the job of spreading information about and awareness of Israel and that includes dealing with press matters and things concerning the Holocaust, as well as organizing tourism events and expositions of Israeli products. In contrast, the Cultural Affairs Section is involved mainly in the arts and strives to introduce art works that we consider to be outstanding as art, even if they are not things intended to promote the country’s image. This is because, in fact, a lot Israeli art is in natural critical of the establishment and is of very high quality. One example is the anti-war film Waltz with Bashir (director: Ari Folman) that was nominated for the Academy Awards Best Foreign Language Film.

- That was a film that certainly attracted a lot of attention.

-

Yes. It is a full-length animated film that deals with the question of whether the Israeli army was involved in the Sabra and Shatila massacre at the Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. It won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film and several other international film awards. In the Academy Awards it vied with the Japanese film Departures for Best Foreign Language Film. The rights to distribute

Waltz with Bashir

in Japan went to Hakuhodo DYMP and the film distributing company Twin. A big debate arose at our Embassy between me and my superior as to whether we should help promote this film because of its excellence as a work of art or whether we should ignore it because of the potential damage it could do to Israel’s image.

The Cultural Affairs officer at the Embassy at the time was a strongly nationalistic woman who worried that showing this movie to the Japanese audience with their limited knowledge of the situation in the Middle East would give them a bad impression of Israel. But I argued that that would not be the case because the Japanese audience should be able to see this movie as evidence that the Israelis are intelligent people who are not afraid to examine the darker sides of their history and to look at themselves with a critical eye and to raise the results of that search to the level of art. I argued that she wasn’t giving the Japanese audience enough credit, that they were a more discerning audience than she thought. For days on end, that argument went on from early in the morning and throughout the day [laughs].

And, this is one of the things that makes me truly proud of the Embassy. I have heard that there are some embassies where local staff members who raise objections are simply dismissed and that is the end of it, but the diplomats at the Israeli Embassy in Japan have the concern to engage in discussion with the Japanese staff members when an issue arises and they listen to our opinions with sincerity. In the end, it is not the person with authority who wins but the person with the best opinion [laughs]. I believe that the most beautiful thing about Israel is not the miracles of the Old Testament or the Mediterranean Sea but this spirit of fairness and respect for others’ opinions. During the 20 years I have been involved with Israel, I have experienced very strongly the Israeli respect for freedom of opinion and freedom of speech.

The result of the extended and intense debate about Waltz with Bashir was that our Embassy did all we could to help with the film’s promotion in Japan, which included the airfare to bring the director Ari Folman and his wife to Japan for the opening, cooperating in the film’s promotion and inviting an expert on Israel to provide background information for the distributors. However, we refrained from having the Embassy of Israel listed as one of the supporters of the film’s run in Japan. If the Israeli Embassy were to be listed among the promoters, it could possible lead some to believe that it was government propaganda. The decision we made was that we would work to bring this film to the Japanese audience as a work of art but we would not put our name among the promoters or sponsors. For me, this has been one of the most significant undertakings of my career thus far. - I am a bit surprised to hear this. I had the impression that an embassy is basically an instrument of the country overseas that operates according to instructions from its country. Especially in the case of a country like Israel with its complex conditions, I assumed the policies of the homeland would be followed quite strictly. Is the division of roles of your Cultural Affairs Section and the Public Relations Section based on a consensus reached within the Embassy?

-

The compartmentalization began to become clearly defined after the year 2000. As a member of the Embassy staff it is a bit of a dilemma, but that is they way things are when you are dealing with the arts. Of course a lot of it depends on the abilities and strengths of the individual diplomat to be able to rebuff criticism from the homeland by saying that the quality of the art justifies it as a program to support. Fortunately, in the 20 years I have been working at the Embassy the officers in charge of cultural affairs have always been people with that kind of personal strength to argue in defense of the art works we chose to support, even if they happened to contain criticism of the country’s policies. I believe that is the mission of a section the deals with arts and culture. I believe that a true cultural affairs diplomat is one who has a high-level philosophical approach to what art is and the strength not to bend to the pressures of government propaganda. I believe that art is the product of people living with purpose and sincerity, and that is what gives me pride in my work.

When Haruki Murakami won the Jerusalem Award and gave an acceptance speech in Israel there was a lot of debate and controversy from a number of sectors and around me as well. When he attended the awards ceremony it was just after the Israeli bombings of the Gaza Strip and Murakami naturally voiced his opposition to the bombings. But, despite his criticism, the speech received major coverage in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. There was nothing about it in the Japanese media but, in fact there is a large left-leaning liberal faction in Israel that are pacifists. Many of the country’s intellectuals and artists want to live in peace and reconciliation with the Palestinians and there are many movements in that direction. There is no restriction of speech or outlawing of films in Israel and you will find people holding anti-war rave concerts and see gay parades. Because Israel is a country of people with different beliefs, there is an underlying culture of debate in which people exchange differing opinions.

Cultural exchange between the two countries

- Your Cultural Affairs Section seems to have a strong focus on contemporary art. Is that the case?

- The established arts that are already recognized are handled by the Public Relations Section, so the Cultural Affairs Section has concentrated mainly on the emerging contemporary arts from the outset. The history of the Jewish race is long but today’s country of Israel itself is a young one that was only founded in 1946. So, when you talk about Israeli culture, it can be said that it actually only refers to the contemporary culture since then. At the time of the founding of the Israeli nation, Jews were coming to Israel from all over the world, and what exists as Israel’s unique culture today is a combination of the culture those people brought from the different countries and the way it has been tempered by the indigenous Middle East elements.

- When introducing Israeli arts to the Japanese audience, how are your programs decided on?

-

One way is by the Japanese promoters and sponsors that approach us for assistance. For example, there are theaters like the Sai-no-Kuni Saitama Arts Theater, the Aoyama Theatre and the Setagaya Public Theatre that have invited Israeli dance companies to perform at their theaters. Then they come back and say that next year they want to invite such-and-such a company, so we add that to the lineup. Also, when there are opportunities to have high-quality Israeli films shown at film festivals like the Tokyo FILMeX or the Tokyo International Film Festival, the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, the Short Short Film Festival or the Tokyo International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, our Embassy may help out with funding and making arrangements.

In the area of film, the Japan Foundation sponsored the 1st Israeli Film Festival in 1992, which was the first large-scale introduction of Israeli film in Japan. After that festival we formed an organizing committee and six festivals were held in all at the Athenee Francais Cultural Center venue. As original programs planned by the Embassy, we have also done things like dance workshops. But, after doing our own projects for a while we realize that the results are often not worth the amount of work that does into organizing the events. The results are usually much greater if we concentrate on existing programs of high quality and have the Embassy provide funding or serve as coordinating go-betweens. I have learned that doing our own home-made programs often ends up bringing little more than our own self-satisfaction.

The other programs are decided is of course when get a request from Israel to promote a specific artist or group, or when we are asked to find a Japanese counterpart to collaborate with an Israeli artist. The function our Cultural Affairs Section performs with regard to these requests varies case-by-case. By the way, when you exclude orchestras, our Cultural Affairs Section invites about 50 Israeli artists and related people to Japan each year. - Besides these events you have mentioned, are doing other things to promote Israeli culture, such as sending out information?

-

In a number of areas we are serving as coordinators between the Israeli side and Japanese side to help make things happen more smoothly. Recently we have been helping Japanese artists go to Israel. Originally this is not a part of our role, but because Israel doesn’t have an abundance of foundations or exchange program offices represented here in Japan like many European countries do, the Embassy is about the only place where people can come for assistance or consultation. For example, when a college girl comes to us and says she wants to write a graduation thesis about dance and asks for our help, we do what we can. Sometimes it even becomes consultation about career or other personal life decisions [laughs]. It is difficult to answer all the needs but we enjoy doing it so it is no trouble.

Although it is not something the Cultural Affairs Section does, our Embassy’s Public Relations Section sends journalist to Israel on occasion, and sometimes they are writers or critics in the arts field that are going to Israel. Since our Cultural Affairs Section does have some budget, we also do some of this type of support, although it is not just for anyone.

In addition, we provide travel expenses for professionals coming to Japan to introduce some aspect of Israeli culture or the arts, and we provide shipping costs for art works for exhibitions or musical instruments for concerts. These sorts of public relations services and events related to Israel that our Embassy engages in are also introduced in our e-mail magazine and on the Embassy’s website.

One of the important missions of the Japanese staff at the Embassy is bridging the gaps that might otherwise exist between Japanese realities and the way Israelis think or the different in our worldviews. There are some works in the arts that may have been very well received in Israel but will not be well suited to the general Japanese audience. I believe it is part of the responsibility of the Japanese staff members at the Embassy to help as coordinators to make adjustments so these works can be better understood, or to find specific audiences where they will be understood.

Looking back on 17 years of the Embassy’s involvement in dance, music, film and theater

- Your Cultural Affairs Section has been in existence now for 17 years. Have you felt any changes during that time? Could we begin by asking you first about contemporary dance?

-

I have felt a very significant spread of interest in Israeli arts among the Japanese in these 17 years. The driving forces behind this growing awareness of Israeli arts from late in the 1990s through the first decade of this century have definitely been contemporary dance and classical music.

Contemporary dance in particular has been representative of the Israeli culture [since 1946] I mentioned earlier. The diaspora that scattered the Jewish people around the world gave them different languages, such as Yiddish and Ladino, and they acquired the languages and customs of the countries they lived in. But after they came to Israel, those languages were replaced by a single national language, Hebrew. In the same way, I believe that dance became a universal language in Israeli society for the very reason that it did not depend on language.

At first there was a desire by the people who came together on the kibbutz farm communes—created to convert desert or marsh lands into agricultural land–to meld the different dances they had brought from their separate countries into a shared dance culture. By the way, the popular folk dance known as Mayim Mayim originated in Israel. There are a number of factors such as the influence of the dance forms of the Jewish people from places like Yemen and the absence of traditional master-apprentice relationships such as you see in classic ballet that led to a development of great diversity, and that diversity became the driving impetus behind contemporary Israeli dance. And, that is also why contemporary dance became a very familiar medium of expression that is close to the people of Israel. At the theaters where dance is performed you will see audiences that include everyone from soldiers to the elderly and children, and they all cheer on the dancers.

Then, with the emergence of the Batsheva Dance Company in the 1990s, the government also realized that this was a cultural asset that would gain international recognition. This led to an active adoption of dance in school curriculums and made government grants available to promote Israeli dance abroad. But it was not done in the form of establishing a national dance company. Instead it continues to be support in the form of partial budget support [for existing companies and programs].

Also, I think that the creation of the Suzanne Dellal Center in 1990 as a center for dance had a major effect on Israel’s contemporary dance world. It supports young dancers and has created programs such as “International Exposure” for Israeli companies to perform new works in front of invited foreign professionals from the dance world. These activities make the Center a bridge to the outside world as well. (See link for an interview with the Center’s director, Yair Vardi ) - Israeli contemporary dance was first introduced in Japan in 1995 with performances by the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, and in 1997 the Batsheva Dance Company came to Japan and had a big impact.

-

The Japan performances of

Anaphase

that were broadcast on NHK national television sent a shockwave through the performing arts world, as people here had never expected to see something like that from Israel. That started a general interest in Israeli dance. Then, beginning near the end of the 1990s we had Japan tours by Israeli dance artists such as Noa Dar, Anat Danieli and Yossi Yungman.

The second Israeli dance “shockwave” came to Japan in 2001 when Inbal Pinto came with the work Oyster . With this people realized that Israeli dance was the real thing, and that led to tours by younger generation artists like Shlomi Bitton, Sahar Azimi, Renana Raz and Emanuel Gat, one after another.

Then a third wave occurred with Yasmeen Godder’s performances, which drew the attention of an elite audience. The performances of his work Strawberry Cream and Gunpowder at the 2006 Tokyo International Festival (current Festival / Tokyo) sold out every night and showed the audiences a new form of Israeli art.

In contrast, the Japanese companies and artists performing in Israel have been limited to the Japanese drum group Kodo, butoh dance companies Sankai Juku, Hakutobo and Dairakudakan, and the contemporary dance artists like Saburo Teshigawara, Dumb Type, Kim Itoh and Grinder-Man. To tell you the truth, the response to these Japanese artists in Israel has been mixed. So, now I want to take performance by some of the most highly acclaimed dance artists in Japan to Israel and see what the audience’s reaction is. I am certain that it will be a great stimulus for the younger generation of artists in both countries. - When introducing Israeli culture, what is the position of classical music?

- For several decades the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra has held a position of great esteem among classical music fans. In the string instruments in particular, there is a great tradition of Jewish master violinists, cello and viola players. Many famous violinists including Pinchas Zukerman, Itzhak Perlman, Maxim Vengerov, Gil Shaham, Shlomo Mintz established their careers at the Israel Philharmonic. Also, conductors from Zubin Mehta (not Israeli but long associated with the Israel Philharmonic) to Daniel Barenboim have established positions of esteem that transcend the effects of war and terrorism in the Middle East. What’s more, Israeli resident conductors Dan Ettinger, currently with the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, and Eliahu Inbal with the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra have been very influential in Japan.

- How about Israeli film?

-

Film is the next most important Israeli art after dance and classical music. Since around the year 2000, a string of Israeli films has won awards at the leading international film festivals, including Cannes, Venice and Berlin. These awards have brought Israeli film to the attention of Japanese festival directors and film distribution companies. As a result, Israeli films have won grand prix awards at the Tokyo International Film Festival and Tokyo FILMeX four times in the last three years or so. Israeli documentary films have also won a number of grand prix and special awards at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival over the last dozen years or so.

In Israel the film industry is coming of age, but compared to Japan the output of films per year is still very few. Despite this fact, however, they have a very high rate of success in international film festivals. I think this is an amazing achievement. However, the subject matter of Israeli films tends to be quite local, which makes it difficult for film distribution companies in Japan to decide whether they will be well received by the audience. The film The Band’s Visit (director: Eran Kolirin) that won the Grand Prix of the Tokyo International Film Festival in 2008 was picked up and distributed by Nikkatsu, but last year’s Grand Prix winner, Intimate Grammar (director: Nir Bergman) wasn’t picked up by any distributor.

At the Tokyo FILMeX festival the 2008 Grand Prix went to the Israeli film Tehilim (director: Raphael Nadjari) about orthodox Jews, and in 2009 the Grand Prix went to Waltz with Bashir . - How about theater?

-

In 2008, we brought an Israeli production of the Greek tragedy

Antigone

to the Shizuoka Performing Arts Center (SPAC). As I was busy doing the promotional work for that, the head of our Cultural Affairs Section suggested to me that we advertise it as a highly artistic staging of a Green tragedy. When I answered that we have to make an appeal for it as a uniquely Israeli staging of a Greek Tragedy, they argued that that will immediately suggest its chain of bloodshed.

In fact, when I tried to promote works like Waltz with Bashir and Antigone as very Israeli works, I kept coming up against the question of what is Israeli-ness separate from the country’s political realities?

Israeli artists are always questioning themselves and what their country is doing, with regard to the Palestinian problem as well as other issues, and that questioning becomes the motivation behind their art works. As long as that is true, promoting Israeli art overseas with always involve the issue of how Israeli artists view the country’s political and social realities.

Toward the 2012 celebrations of the 60th anniversary of Japan-Israel relations

- Could you tell us as much as you are able to at this point about the schedule of events planned for the 2012 celebrations of the 60th anniversary of Japan-Israel relations?

-

Planning has been delayed somewhat by the repercussions of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, but one of the main highlights will be a joint Japanese, Jewish and Arab production of

Women of Troy

directed by

Yukio Ninagawa. There will also be numerous dance performances in Japan by many of the internationally recognized Israeli dance companies we mentioned earlier. As for the Japanese companies that will be performing in Israel, names like the

Condors

and

BABY-Q

have been brought forward as candidates.

In film there will be a special feature of Israeli film from the 1960s and 70s at the Tokyo FILMeX festival. We are also approaching a number of organizers such as the Tokyo JAZZ festival. - We hear that Yukio Ninagawa’s production of Women of Troy will be staged with Jewish and ethnic Arab Israeli actors.

-

Preparations began in 2010 as a joint Japan-Israel production. First of all, people from the Cameri Theatre of Tel Aviv came to Japan in 2010 for a workshop on Japanese theater techniques at the Sai-no-Kuni Saitama Arts Theater. As part of the training in traditional Japanese theater conventions at that workshop, they had actress Kayoko Shiraishi instruct the Israeli actresses in the traditional bent-knee, dropped-pelvis walk of Japanese women, which brought complaints of lower back pain from the Israelis actors [laughs].

The script for this play is written in Arabic, Hebrew and Japanese. Plans call for Ninagawa to go to Israel early in 2012, to hold official auditions.

However, from our long years of experience in this job, we know that it is naive to believe that this type of peace exchanges in the arts will necessarily be successful. Because of the complex and deep-running emotions and conflict between the Arabs and Jews of the region, it is little more than self-indulgence on the part of Japanese to think that they can go in and try create a harmonious situation. Of course Ninagawa understands that all too well and I am sure that he has a well thought-out plan for the production and will work hard to make it successful.

In fact during the self introductions at the first meeting of the actors there was an incident of friction, though not actually a fight, between the Arab and Israeli actors trying to get their own way. While most of the Japanese were shocked by this, Ninagawa remained calm. While playing the role of the humble intermediary, he nonetheless went on to say that he hoped everyone would bring all of their passion and emotion to make a truly creative stage. It was clear that this will not a feel-good friendly peace exchange, but I am really looking forward to seeing what kind of stage it will be. - Works dealing with political subjects always have to resist the tendency to gravitate toward propaganda, and there will always be people who are critical of the results no matter what they are. Nonetheless, in order to create works of art, I guess you have to believe in the power of art to bring people together.

-

Because the people and the regimes are so different. For example, Iran is very critical of Israel politically but Iranian films are very popular in Israel and you often hear people make comments like, “Abbas Kiarostami’s films are really interesting, aren’t they?” The Israelis always say that “the individual and the regime are different and the political establishment and people’s individual talents are separate realms.” I believe that is how we should look at things.

In the end, I believe that cultural exchange should provide results that give us the opportunity to enjoy glimpses of the deeper aspects of the times we live in and things that you might describe as the 3-dimensionality of the world or its organic depth. However, to tell the truth, I think we should forget the name of the country something comes from at first and just go to see it because it looks interesting. And then, if the work was interesting you do some research and find for the first time that it was a work by an Israeli. That is the spirit with which I want to continue presenting works of art.