- In recent years your areas of activity have expanded, with video works and teaching at the university level. Could we begin by asking you to tell us about your current projects?

-

I have just returned from Sydney, Australia, where I was shooting a 3D video work to be presented at the Shanghai eArts Festival. I will set up screens in a hexagonal form and show 3D videos taken from six directions. Ordinarily, as dancers we perform facing the audience, but with this installation the audience can walk the full 360 degrees around the dancers as they watch the performance. What’s more, it’s 3D, and that lets them experience a world with a different type of reality. We will also be participating in the Yokohama Triennale with a different installation.

Of course I am also doing our KARAS performances. At the Montpellier festival in June we performed our work Miroku, which we are now touring the world with. Just after that we flew to Sweden to shoot another video work. The photographer Bengt Wanselius invited me to visit a small island where the movie director Ingmar Bergman had lived before he passed away in 2007. He said that Bergman had loved the beautiful light of the island. The light was indeed beautiful, so I used it as the site to film Rieko Saito dancing. This was a self-financed production with Wanselius in charge of photography and me directing.

As for festivals, I participated again this year in La Milanesiana festival that is held over the course of a month using several theaters around the city of Milan. This is a festival that brings together literature, video and music in various forms of collaboration, such as authors reading their works with musical accompaniment or video and music collaborations. This festival has brought together a high varied group of artists including Phillip Glass, Laurie Anderson, Umberto Eco and Lou Reed. Last year I did a performance of Black Water at La Scala Theatre. It was a collaboration with the Irish writer Colm Toibin, who has a work titled The Blackwater Lightship. He did a reading of his work before my performance. - On August 9 and 10, 2008, you had your first performances ever at the hall in the Kameido district of Tokyo where your studio is located. The work was titled 36 dance books – Proper Posture.

- I always wanted to perform once in our local community, and I danced in this one myself along with the boys and girls who performed in our Dance of Air performance. In terms of positioning as a project, it was something close to a study session. Next I would like to do something closer to a “studio performance” program as well. I want to do experimental works, and this is a starting point in that direction.

- Now you are teaching at Rikkyo University. What type of courses are you teaching?

-

At the university I am a special instructor teach a course in a department called Film and Physical [expression] Studies in the Department of Contemporary Psychology. I talk about theoretical aspects based on my experiences and we do workshops. We have both students who are primarily interested in film and students who are interested primarily in theater and dance, and of the two there certainly more interested in film.

For example, in our History of Physical Expression course I try to get the students thinking about the body; what their body is and what their bodies are feeling. Thinking and living with, dealing with our bodies are both life-long occupations. In other words, we study the body as a prerequisite to expression. I get them to think thoroughly about how to approach their bodies, and the act of “breathing” that I am always talking about. I have them think about looking at film from the viewpoint of the body, or nurturing one’s sensitivities and perceptions of visuals from the viewpoint of the body. The methods of expression they will eventually use are a matter of specific techniques and it takes time to acquire technique, so I tell the young students not to rush things and spend their time initially in refining and polishing their perceptions and sensitivities and to find viewpoint that are meaningful and relevant to them. I tell them that at least they should have the ability to express their opinions clearly in their own words at any time. So, I often have them write reports. - You definitely seem to be a total creator with regard to your works, without distinguishing between choreography and stage design as separate arts.

-

I believe it is eventually a matter of my individuality. From my experience, the methods you use to arrive at a form of expression, the way you find a methodology to lead you toward the objectives and subjects you were originally interested in, or gaining the perspective or viewpoint you need, is not a matter of simply proceeding in one direction. I believe that it is all right to use a number of different approaches.

Speaking about my case, it was while applying myself seriously to ballet that I was able to realize what kind of visual expression I was inherently most interested in. And it wasn’t until later that I realized it was because I had the will to pursue some kind of sensibility or perception that lay on the other side of “visual desires,” the will to pursue something rooted more deeply in the human experience. Whether it is a work using the body or a work using video, I experience the greatest joy when a work achieves a strong and clear sense of that pursuit of connections that lie deeper in the human soul. - Since 1995 you have been conducting your “Saburo Teshigawara Education Project (S.T.E.P.) in the UK. And you have been in educational activities that are recently gathering increasing attention in Japan.

-

The London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT) has many educational programs, and that is where I first got involved these projects. The first one I did was with handicapped children, and the next one was a project for middle school and high school students in three London districts. For that project we painted the walls and floor of a small space in the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in very strong, bright colors to do performances titled Invisible Room .

I wanted the young people to discover that they could achieve something by doing dance. And I wanted to try creating a work that was based on what they wanted to do. Dancing may not have been something that they needed to do, but once they got together and began practicing, that gradually changed. There were suicidal children, there were children who were getting into fist fights backstage. It was children in their most difficult stage of adolescence and there were children with bad home environments, which meant that we had to deal with their personal problems, and that made it even more interesting for me.

After that project, the next one I did was with the visually handicapped. It was a project of London’s The Place and there were blind people participating in it. For that project we took a good amount of time doing an extended workshop. When I couldn’t be there, I gave them a video and instructions what to do. Through that workshop we created a work titled Flower Eyes . This happened to be an exchange project with Helsinki as well and dancers from Helsinki who wanted to participate were involved too. - That is where you met the young blind man Stewart Jackson who performed in your Luminous (2000) production, isn’t it?

-

Yes it is. The woman who was his care-taker brought him to the program because she had the idea that he would benefit from the experience of dance. Even though they can’t see, it is very important for visually handicapped people to go and “see” things, which means go to feel things. And it is especially meaningful if they get involved in doing something with other people.

Besides Stewart, there was a very weak-sighted teacher from a school for the visually handicapped. I did a workshop on the relationship between the different parts of the body and breathing. Since Stewart is a young man he responds to strong forms of expression like jumps and spins and to strong music. On the other hand, the female teacher’s movements were very smooth and beautiful. In the workshop their individuality became even more accentuated and I felt a great purity to it. Watching them I got the very strong feeling that we can take our potential to much higher levels and that we could use our inherent capabilities in even more lively and vital ways.

Stewart was born blind and can’t see at all and he can’t do anything by himself, so his feelings of hesitancy and his sense of fear are very strong. For that reason he often has to suppress himself in daily life, but when that restraint is removed it can give birth to very strong expression. The strong potential and mental strength he has within himself comes out very directly.

In 2001 we presented the work Luminous at Tokyo’s Theatre Cocoon with the British actor Evroy Deer participating, and after that we toured this work internationally. Today, Stewart has reached the point where he has created a work of his own. - What kind of work is it?

- It is a wonderful work titled “Angel’s Journey.” Its theme is one of Stewart’s favorite things, angels. In it there are moments of intense, violent motion, but I believe that for him that intensity is an expression of approaching what he seeks. Besides being blind, Stewart also had a so-called learning disability, he had trouble putting memories in order. He has memories but since they are not structured normally, he had trouble speaking coherently. When he first started attending the workshop he would often lose track of the order of movements in a piece and he almost never spoke. But we found that as he continued the physical exercise of the workshop he gradually became able to put the parts together. He became able to memorize physical movements, and his ability to memorize physical movements became the impetus that enabled him to put verbal, linguistic elements together and now he has become able to speak like he wasn’t able to before. This amazed me, and made me think again about the potential of physical movement and exercise.

- So, it seems that your aim in working with people of completely different sensibilities from yourself has been not to get them to learn your form of expression but to help them bring out their own sensibilities and give form to them.

-

That’s right. That’s why I say that I am not an educator. Instead, there is the interest in being involved with other people’s bodies and physical expression and discovering things I don’t know. I don’t work with them because they have handicaps but to help bring out the things that are hidden inside them, to dig deep and bring out what can be brought out. I want to know myself, and the process of getting to know other is a similar process.

That’s why in the Dance of Air program what I want to communicate to the middle school students is the question, “What do you want to discover for yourself?” It is certain that the things they have in their minds are important to them, and that there is undoubtedly something of value that they have as people. But, if they don’t know how to bring that something out, we can say to them, “How about trying this?” That’s what technique is for and that is why I work so exclusively with teaching how the truly basic movements come out.

That is also why I don’t try to push them to give premature expression to what is inside them, even for university students. - I would like to go back for a moment to ask you what types of things you were doing when you were starting out as an artist.

- In my early career I spent the longest time studying ballet. After that I participated in various events and once every three months I worked with video artists and people who were doing rock-ish noise to present work at the “Antenna 21” space in Tokyo’s Shibuya district. That was around 1984.

- At the time, the term contemporary dance didn’t exist in Japan, so what did you call the things you were doing?

- We called it “moving works.” I didn’t like the term modern dance and I didn’t think of it as butoh. I liked theater too and often went to the small theater called Kyu-Shinkukan Gekijo, which was in a converted factory building. I danced there under bare light bulbs in the entrance hall, and I think that may have been my maiden performance.

- One of your expressions from an interview that impressed me very much and I have always remembered is the statement, “There are no internal organs in my body.” That suggests a vision of the body that is different from butoh and different from classic ballet as well.

- I still dislike the term nikutai-teki (bodily). At the time I was absorbed in the discovery of one’s body and how to express the things I discovered. I wanted experience concepts like “air” and “material” and “non-material” from the perspective of the body and give expression to them. I felt a kind of emptiness or severance in the word “air.” So, in music as well, my direction was toward noise, not in the minimalist sense of the “post-modern” artists like Steve Reich, but in the sense of “un-performed sound is music.”

- And that is what led to the “individuality” you mentioned earlier in which you plan everything from the music and lighting to the stage design in your works?

- I didn’t see anyone in the world of dance at that time that I could identify with in terms of artistic sense. Rather, I felt that artists in film or “noise” musicians may have been closer to me in artistic orientation. For a long time I felt that I didn’t need a teacher and didn’t want to be taught by anyone. But in fact, I was being taught and I was learning things [from others]. And, as I was studying ballet I was thinking, “Why do I have to do this, this isn’t in sync my body at all.” That feeling of dislocation was my starting point. It was a very important experience.

- Then, as an artist who could not be categorized into any of the existing forms and whose style of work was hard to put a name on, you came to the attention of the world when you entered a work titled Kaze no sentan (La Pointe du vent) at the 1986 Bagnolet International Choreography Competition. It was a work that shocked and stunned many people because it took as its motif the seemingly simple process of falling or crumbling down and then rising again. This was shocking because dance has always been an exercise in balance and neither ballet nor modern dance had ever permitted falling, or equated falling with failure. When I saw that repetition of falling and rising again, I felt that I was seeing something I had never seen before, a new language of dance, a new form of dance vocabulary. How did you come to conceive of that form of movement?

-

As I have often said, meeting Kei Miyata was an important part of it. At the time, we were doing long workshops where we would spend hours doing the same movements over and over. Miyata disliked dance and didn’t have experience in dance. But she had a very strong desire to do some form of physical expression. And since she had no [dance] technique, she didn’t have a basis for movement. See that, gave me the idea of trying to approach movement by first making the body empty and “feeling from within the [empty] body.” Many things are moving within the body. There is the breathing and things like “the flow of air.” In order for us to expand our sensitivities and perceptions, I thought that rather than starting from the assumption that there is “something” [like “dance”] already existing, we should start from the point where there is “nothing.” That became my point of departure.

By nature, people want to think that they possess something, and we all have a self-defense, or self-preservation instinct that functions to protect us from the viewpoints of the other and from external pressure. But for an artist whose mission is expression, the challenge is how to remove that self-defense instinct which is a normal part of everyday life.

So, when I proposed, “An empty body would crumble and fall, wouldn’t it?”, Miyata immediately understood intuitively what I was saying and she just went blank, as if suddenly deflated, and she crumbled to the ground. And, it wasn’t a crumbling from the legs, but a crumbling from the head. And it was incredibly beautiful to watch. Her body collapsed so smoothly and beautifully, it was like watching a slow-motion film of a giant building collapsing. And it had such a material sense that you could almost see the clouds of dust and smoke rising as she collapsed. That made me think, “This is not movement, it is shitsukan [a Japanese expression that includes both “sense of material” and “material quality/qualities].

In this way, Miyata has been the source of all kinds of imagination for me, and our techniques of expression are things that Miyata and I have created through the medium of her body. None of our vocabulary, with words like shitsukan [sense of material] or “breathing” and “air,” or “collapse” and “crumble,” or “solidify” and “melt,” or to become like “powder” or “gas” and melt into a space, are really about “movement” as such. They all based on an initial change in consciousness or sensibility that enables the person to become a body with a different “material quality” or a different “material sense,” and then that becomes movement. And that gives birth to specific body lines [of movement]. When I saw Miyata crumble to the ground, I saw a clear embodiment of the process, that journey if you will, and I thought it was beautiful.

In modern dance and ballet, the dancer moves as if movement is natural. They practice until step follows step skillfully and the dancer reaches the point where they can move without thinking or without any particular feeling or sensibility in mind—like a machine. But I have doubt about such a process. If you can move just by moving, then what is the purpose of the time spent studying and rehearsing in the studio?

If the most important thing is to present works, isn’t it enough just to rehearse the works? In Europe there are many dancer groups who spend all their time practicing, and their minds are so solidified around the ideas of how certain information input can produce movement that their bodies are only good for that kind predefined process. The people doing modern dance in Japan were all students of Cunningham and Martha Graham and they were all doing the same things. And when I saw the contemporary dance people were doing in France in the latter half of the 1980s, it all appeared to me as just forms, and it gave me a disappointing realization that everyone was doing the same type of thing.

In short, dancers were moving in response to sound, or moving to the dictates of an architectural environment or the conditions/atmosphere on a stage, or moving to the dictates of a [music] composer, and as long as they were moving within the confines of such couplings, their movement couldn’t help but become formalized. I am not categorically opposed to formalization in expression but, although this may be a matter of taste, I don’t think mass-production-like dance is necessary in creating works that will stand as original works of art. Dance is not a form for the purpose communicating information. What is important with dance is whether it is alive or not. That is what I felt when I met Miyata in the 1980s, and I knew from that time that I didn’t want to do dance that relied on form, formalized dance if you will.

It was at a time when we were doing a lot of studio work on this alternative type of movement that I decided to enter a work in the Bagnolet International Choreography Competition. The requirement was that it be choreography for groups of three or more dancers, so I created my first group piece. And when we performed it, I got the feeling that it had communicated something to people. - It did more than just communicate. It was fervently and emotionally received.

- It was an amazing response. Because Bagnolet was a “choreography contest” some people said that my work was too improvisational. But, today that way of thinking about where a piece is choreographed or not and the conception or perception of what that means has changed a lot. I may be the one who broke down some of the preconceptions at that time.

- After Bagnolet you got more offers than the choreographer who won first prize. And one of the offers let to your presentation of the work Constellation at the Festival Sigma De Bordeaux. I remember being slightly stunned seeing that work because you partitioned the stage in two. Usually, the stage is something that performers try to use as fully as possible, but you divided it in half with tin walls and danced within a space defined by the material quality of tin.

-

That’s right. We did a lot of crazy things like marching around beating on a steel box.

The performance at Bagnolet brought offers that suddenly filled our schedule for seven or eight months in advance. We had to prepare one new work after another. We would return to Japan and have to begin right away preparing a new work for our next engagement. After Bordeaux, we had an engagement to perform at Studio 200 in Tokyo’s Ikebukuro district, and then I went to Vienna as instructor for a workshop, which turned out to be a very important experience for me. The participants for that workshop had come from all over the world, and for a month I conducted full-day workshops each day from morning to night. During that month I really had to consolidate my thoughts and decide what it really was that I wanted to communicate, and that experience truly clarified in my mind what physical expression meant to me. - After that you performed at the Pompidou Center in Paris and at the Spiral Hall n Aoyama, Tokyo. There you created a set with materials of hard qualities like wire and glass.

- It was around that time when we were finally beginning to sense our direction as a group. Now that we performing in both Europe and Japan and from some stage we were doing more performances in Europe than in Japan. At first we made France our base in Europe, but I didn’t like French contemporary dance, and so, when we were invited to perform at Theater Am Turm (TAT) in Frankfurt, Germany, we decided to switch our base there.

- It was a great era in the performing arts when the festivals of Europe were very active and their directors full of ambition to produce new works. And there were lots of uniquely specialized festivals.

- The theaters also had well-based policies and their directors were well qualified and responsible. When TAT first asked me to visit them they told me that they did not intend it to be a short-term relationship. They said that if the invited me to perform at their theater they wanted it to be the start of at least a six or seven-year relationship. They weren’t interested in a one-off encounter. That really impressed me when I heard it, and it made me feel assured that I could make a serious creative challenge there, devoting all my energies.

- You have also been commissioned to direct and choreograph staging of the Paris Opera Ballet and I believe that your methods have been recognized in Europe for their universality.

-

For a long time we have been studying elements like air and gravity and buoyancy, how to collapse the body and how to re-build it and I believe it is the universality of these elements that people perceive. These universal things have to be have to constantly discovered, learned and technique and maintained as ways to use the body, and with our experience performing overseas and seeing the response, I felt very strongly that what we were doing had been correct.

At Canada’s Festival Internationale de Montreal and when we performed at the Chaillot Theatre as well, there were clear responses from the audience. It impressed me when one staff at the Chaillot Theatre hold me that in all the years he had been working there he had never felt more from a dance performance than he had from ours. With dance it is not a question of what is good or popular at the moment, the measure becomes what you actually feel. That is what I have been pursuing from the beginning, the “strength” that dance has as a form of expression. - Can you tell us in some specific terms what you actually teach in your workshops?

-

As living beings, we can’t live without “breathing.” And we can’t breathe without the “air” around us. In this sense, we can think of these mechanisms, including the air surrounding us, as the “body” in a holistic sense. Also, “gravity” acts on the body. We start from by getting the workshop participants to have a full experience of the “consciousness” that feels this gravity and the body and also the act of “breathing.” I tell them that there is no need to think about what memories the body may have, what they might be thinking now, or how to understand this piece of music. I tell them, let’s just concentrate on feeling our own bodies. Before understanding there is feeling, and from there it is possible to proceed toward conscious understanding.

In specific terms, we begin with simply concentrating on breathing. “Breathe in, breathe out, breathe in, breathe out,” we repeat. When I tell people to concentrate on their breathing, most people tend to close their eyes, but if you close your eyes your sense of balance suffers and your consciousness tends to focus more on sound. So, we do the breathing exercise with our eyes open. But, after a while people begin to get bored. They begin to think, “What is there in just breathing?” When they begin to get irritated like that they naturally want to do something different, and that is when things get interesting.

Then I change to, “Breathe in, breathe in again, you can still breathe in more.” And then I tell them to exhale slowly, very slowly. By doing this, I get them to be conscious of the “breadth of breath.” After having them exhale as much as they can I tell them to begin inhaling slowly. Just as a ball thrown up into the air defines a parabolic curve and falls again without stopping, our breathing is basically a ceaseless cycle that goes on unconsciously, but I tell them to be aware of the moment when they start to inhale and when they start to exhale. In the process, that becomes a rhythm. And, it can also be called a form of movement. Them, we use this breathing [rhythm] as a guide to stretch out the arms in unison with the breathing.

In ballet it is called preparation when you step back before a movement, and there is that type mechanism in all movements. For example, before breathing in you can do a slight exhale, or do a slight inhale before exhaling. In your couple actions in this way, you get a dramatic sensation as loosening yourself.

In the workshops we focus exclusively on this type of breathing and movement. Removing the expressive psychological device of saying, “That’s enough,” after breathing out fully, we first concentrate exclusively on breathing. Then we coordinate the breathing with movements and begin to harmonize them. The reason that Stewart became able to walk alone is that we had him practice coordinating breathing with the movement cycle of the heel, arch and toes leaving the ground in succession in the walking process. For him, breathing has become a source of harmonization, and taking away breathing would be like taking away a blind person’s cane or handrail. It is not as if they are putting all these things together consciously, but they have an “automatism” that enables them to do it automatically. Once they are able to consciously control their breathing, it possible then for them to add their own conditions, or coefficients if you will, and put together their own methodologies.

I believe that deep in the body there is a final “sense” that remains after a process of differentiating something out. I enjoy trying to discover that sense, and when I am working with young people I find that there is still more to discover. There is never enough time but, I believe that I have a [movement] language sense—my method—that is different from dance until now, and I want to continue pursuing it. Be it ballet or be it Noh theater, these are not things that any one person as created. They are traditions that have been created over long periods of time. When I talked about this quest of mine with a journalist from Liberation , he said I sounded like a Don Quixote (laughs). Someone in pursuit of the “endless dream.” But, for me that is a very positive thing. - Can you tell us something about your plans from here on?

-

September we will be presenting Here To Here at the Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater, and in December I will be working on in a new play at Theatre X in Tokyo’s Ryogoku district. It is based on a text by the Austrian writer Robert Musil, and I will be directing and playing the lead role in it. Musil is a very well known thinker and novelist in Europe and the script we will use is based on his work Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften ( The Man Without Qualities ). It is not that I am especially set on doing drama, but I want to experiment with what can be done with only the voice and body. I believe this performance will be quite different from anything I have done before, in terms of how the body is used.

I don’t really want to be choreographing dances right now. I believe that what I can do as an artist will continue to develop based on my individual ideas, but what I am most interested in now is not just that, but the parts that do not come from the individual, or how to deal with the parts that cannot be done by the individual alone. Earlier, I wrote that I want to be involved in a revolution that will take a thousand years. That is not an exaggeration—although the words may be (laughs). That is what I am really interested in.

Saburo Teshigawara

The continuing expansion of the world of Saburo Teshigawara, an artist who has already left a big footprint in contemporary dance

Photo: Norifumi Inagaki

Saburo Teshigawara

Saburo Teshigawara began his creative career in 1981 in his native Tokyo after studying plastic arts and classic ballet. In 1985, he formed KARAS with Kei Miyata and started group choreography along with their own activities. Since then, he and KARAS have been invited to perform every year in major cities around the world.

In addition to solo performances and his work with KARAS, Teshigawara has received international attention as a choreographer/director. In 1994/95 he choreographed for the Ballet Frankfurt at the invitation of William Forsythe, Le Sacre du Printemps for the Bayern National Ballet in 1999 and Netherland Dance Theater I in 2000. In February 2003, he was invited to choreograph a new piece AIR for the Paris Opera. Also, for the Ballet du Grand, Théâtre de Genève, he choreographed Para-Dice in 2002, and recently VACANT in May 2006.

He has keenly honed sculptural sensibilities and powerful sense of composition and command of space, as well as his decisive dance movements, all fuse to create a unique world that is his alone. Keen interests in music and space have led him to create site-specific works, and collaborations with various types of musicians.

Teshigawara has likewise received increasing international attention in the visual arts field, with art exhibitions, films/videos, as well as designing the sets, lighting and costumes for all his performances.

Besides the ongoing workshops at the KARAS studio in Tokyo, he has been involved in many educational projects. S.T.E.P. (Saburo Teshigawara Education Project) has continued since 1995 with the partners in the UK, in a program that creates performances as the culmination of year-long projects. In 2004, he was selected as a mentor of dance for The Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, to work for one year with a chosen protégé(https://www.rolex.org/rolex-mentor-protege). In 2006, he has begun teaching as a special instructor in the Department of Expression Studies, the College of Contemporary Psychology, St. Paul’s (Rikkyo) University in Japan, where he teaches movement theory and conducts workshops. Through these various projects, he continues to encourage and inspire young dancers, together with his creative work.

Interviewer: Maimi Sato

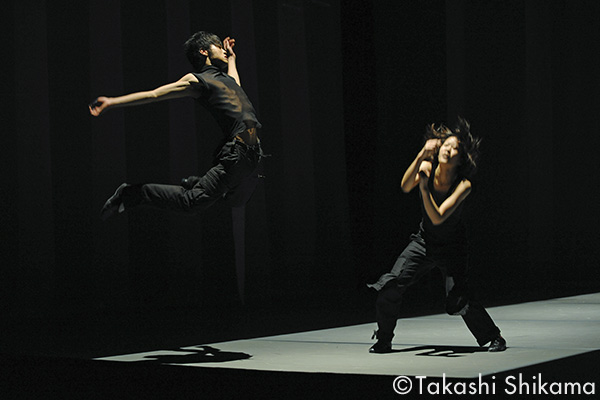

Dance of Air

Photo: Takashi Shikama / New National Theatre, Tokyo, 2008

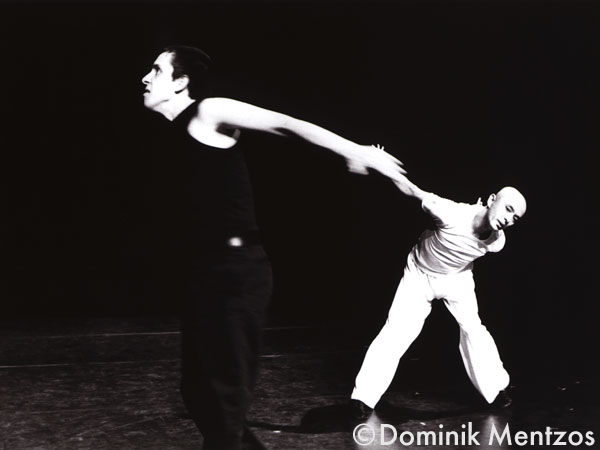

Luminous (2001)

Photo: Dominik Mentzos

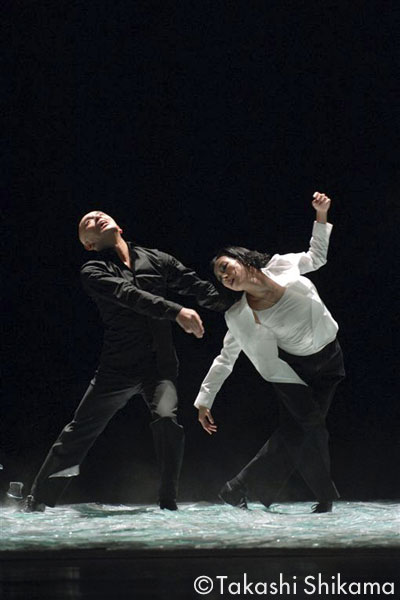

Glass Tooth

Photo: Takashi Shikama / New National Theatre, Tokyo, 2006

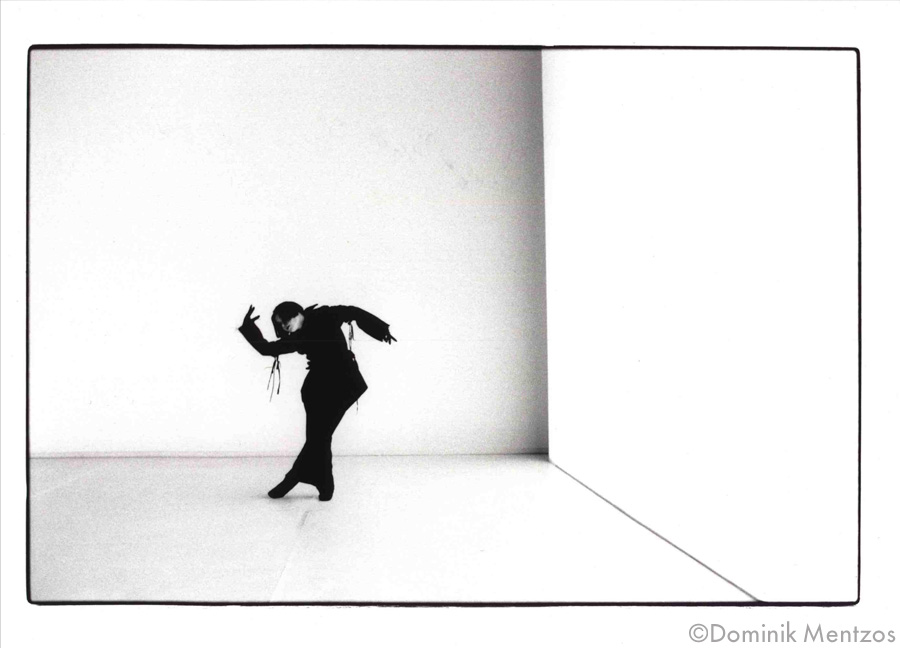

Photo: Dominik Mentzos

Here To Here (1995)

Photo: Bengt Wanselius

Related Tags