Chikara Fujiwara’s Background

- You were born in Kochi Prefecture and you moved to Tokyo alone when you were 12 we are told. Would you please begin by telling us about your childhood?

-

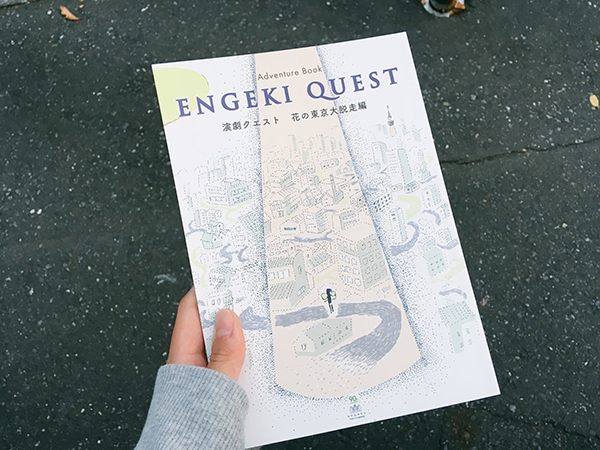

I loved books, and during my elementary schools years I spent so much of my time in the library, reading all the books I could. It was the time when the first home video game players had come out, but since they weren’t very high-spec yet, I mostly read game books. They gave you choices so you could read through them as you liked, and that was really fun, so I spent my time alone reading them. Looking back, I guess that experience is the root of my ENGEKI QUEST works today. I got good grades in school so people praised me, but I soon got tired of being good in a small town and limited environment and I wanted to get out into a world of greater knowledge as soon as possible. So, I took the entrance exam to go to the Kaisei Academy Junior High School in Tokyo. In fact, my first choice was the Nada Junior High School, but I didn’t pass their entrance exam. If I had gone to Nada in Kobe, it would have been at the time when it was struck by the Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake. That same year, 1995, was the year of the Aum Shinrikyo cult’s sarin gas terror attack on the Tokyo subways, which was a big shock for me.

- What were your junior and senior high school years like?

- At the time, all the students just wanted to study hard to get into a good university, and felt that wasn’t what I was interested in. There were some students who were interesting, but as an environment didn’t suit me. In junior high, I played the part of a good student, but when I got to high school, something snapped inside and I started going to the bars and mah-jong parlors in Ikebukuro. There I started talking to people older than me, and I made friends with LGBT people and Korean-Japanese people. Those places where I found people with different values were much more thrilling and interesting for me than the homogeneous environment of school.

- Did those kinds of people have a big influence on you?

- Yes, it probably was big. At the mah-jong parlors it didn’t matter what school I went to and as long as you were good at mah-jong you were accepted as an individual and they would treat you as an equal. That is probably what I liked about it. That was in the 1990s after the bubble economy had burst and a feeling of hopelessness had supposedly begun to spread in Japanese society. Sensitive people of my generation might have become fans of young musicians like Kenji Ozawa or the bands that came to be call the “Shibuya sound,” but perhaps because I had gone to the bars and mah-jong parlors of Ikebukuro, I wasn’t influenced by that kind of subculture. I didn’t have any encounters with theater either. I was just trouble by what I should do about the gap I felt between school and the people at the bars and mah-jong parlors. Eventually, I ended up spending two extra years studying before I finally got into university, barely. The reason I choose Rikkyo (St. Paul’s) University is because it was right near the mah-jong parlor. But that parlor quickly went out of business, so I became a serious student again (laughs).

- At university you studied political science.

- The reason I chose political science was a stupid one, just to convince my parents I was studying something legitimate, but I had the good fortune of meeting a very good professor in Michitoshi Takabatake as a result. He was one of the three founders of the Beiheiren, a coalition of anti-war groups during the Vietnam War. From professor Takabatake and from Akira Kurihara, who had dealt with the Minamata disease issue for many years, and from the assistant instructor Akifumi Kasai, I was taught about the history and philosophies behind Japan’s social activist movements. From philosophy and political science that I learned that no answers exist to explain the world we live in. It was a world that was completely opposite to the experience of studying for entrance exams. At university I also watched a lot of movies. I did absolutely nothing in the way of looking for post-graduation employment, but on an introduction from Reiji Suzuki, an upperclassman in one of the seminars I took who now works as a critic, I got a job at a local workplace in Yokohama named Kapukapu. It was a place where they had people with mental disabilities and I like the ideals behind it all. At the time, the partner I was living with had mental instability and I got to the point where I couldn’t continue to work. Unable to work and with no money, I was in a bad way, and the people who helped me out in that time of need were my network of friends from the bar I frequented when I was a student. And it was with the company whose president was a regular customer of the bar that I got a job again. In the end, it was the network of friends from the bar that saved me (laughs). It was a company that specialized in urban development projects and I went out on fieldwork, attended meetings with local government officials and edited pamphlets and did ghost writing, all of which built a foundation that contributes to my creative work today. At the same time, I worked part-time at a used book store in Komaba Todai-mae. It was there that I met Yuna Tajima, who worked as a producer at Komaba Agora Theater and started going to see plays there at her invitation.

- So, Komaba Agora Theater was where you first were introduced to theater, was it?

- Before that, I had worked part-time at a bar where Tamae Ando, a leading actress of the company potudo-ru , also worked and started going to see their plays. At Komaba Agora Theater and its studio theater Atelier Shumpusha I remember seeing the early works of the company Chiten’s Motoi Miura and Shu Matsui . All of them were very intense experiences for me, but since I didn’t have the money to spare, I couldn’t make a habit of going to plays.

When I was working at the used book store, I became friends with a group of young people in the Shimokitazawa area of Tokyo. At the time there was a popular movement to stop a planned urban development project for the Shimokitazawa area, and these young people were involved in it. Some of them were living together in a house in what we would today call a “shared house” arrangement. There happened to be an opening in the house so I was able to get a room there. Every night there would be a party-like gathering with interesting people coming and going. After a while, a group of us with shared interests started a free-paper magazine. In Shimokitazawa I also met the editor (Japan edition of Wired , etc.), writer and eventual Webzine editor and publisher Akio Nakamata, who I was able to learn a lot about editing from while drinking with him, which I feel turned out to be very important in my career later. And, at the suggestion of my partner at the time, I applied for a job at a publishing company and was fortunate to get a job there.- That began your life as an editor, did it? Living in a shared house, editing a free paper and all turned out to be progressive experiences, even though they came partly by chance for you, didn’t they?

- I believe I have always been fortunate in the people I have met. When I was working at the publishing company, I worked primarily on editing books at first. It was enjoyable and I learned the skills of editing, but the working hours were long and the stress of personal relationships and pressures of corporate life took their toll, and after two years I was suffering from depression. I became painfully aware that depression is something that could strike anyone. The experience made me decide that I was going to stop trying to live amid the pressures of organization and companies and instead I would go it alone and live freely doing things I wanted to do. Just as I was about to quit the publishing company and go freelance, at Nakamata-san’s introduction I was able to put together a book for the TBS broadcasting company’s show “Cultural Talk Radio – Life.” Through that experience, on of the show’s personalities, the critic Atsushi Sasaki (leader of the music label HEADZ, professor of literary arts at Waseda University, author of numerous books on contemporary trends) asked me to come work on the editorial staff of the magazine ex-po. Ever since then I have worked freelance.

When I was helping out with Sasaki-san’s work, he often invited me out drinking after work and he often talked about theater. As we drank, I learned a lot about the basics of critical language used in intellectual discussions. I also went along with him to interviews and learned a lot about his art of interviewing people. While working on ex-po , one of the important experiences for my future was meeting Toshiki Okada of chelfitsch. I was in charge of editing his interview series, which gave me the opportunity in 2007 to see his play Free Time , and I felt that it expressed in a very fresh and cool way some of the drifts of contemporary society. That started me seeing contemporary theater by companies like hi-bye, Sample and Tokyo Deathlock, and I felt a close affinity to the feeling of depression that they expressed and the methods and energy they used to overcome it.At the festival of plays the premiered at Komaba Agora Theater in 2009 under the title Kirenakatta 14 year-old – Returns (a festival of six original plays written by sic playwrights on the common theme of a series of child murders that occurred in Kobe in 1997) the leader of the company Faifai, Chiharu Shinoda (b. 1982, director and writer, co-founder of Faifai left in 2012) currently based in Bangkok) asked me to join in to make an “unbound magazine.” As it turned out, the magazine wasn’t finished in time for the publishing deadline, so I ended up staying at the theater every day turning a rotary printing press, and as a result I saw almost all of the performances from the audience or on the TV screen in the lobby. Seeing the same plays being performed over and over that way definitely changed my way of viewing theater. Watching the theater makers at close quarters, I found it very interesting to see what they were thinking, and what their contemporary producers and editors were thinking. The generation of playwrights like Chiharu Shinoda and Yukio Shiba participating in Returns had a sense of something like euphoria that is not present in the works of the earlier generation of theater makers such as chelfitsch and Potudo-ru that I mentioned earlier. And I feel that their sense of happiness was something that the critics weren’t expressing. In any event, I felt that there was a passion and energy at the time that was creating new things day by day. And I felt that the critics’ vocabulary wasn’t keeping pace with these new trends to be able to express them. So, I felt that I had to do something about it and I started contributing play reviews to the small-theater review webzine wonderland .

How the ENGEKI QUEST works were born

- The first work you created as an artist was ENGEKI QUEST (Theater Quest). We are told that this work resulted from a request from Haruo Kobayashi of the Yokohama art space blanClass (Founded 2009 in Yokohama as an art space to bring together artists, arts professionals, students and researchers of contemporary arts). Would you tell us about the process leading up to this first work?

-

Kobayashi-san’s request was an openly vague one for me to create something “performative.” But I felt that I wanted to create something, so I decided to try it. At the time, I had already left Tokyo and was living in Yokohama. One night, a man that I often drank with at a bar I frequented said, “People often move “upwards” in the urban context (like in Japanese moving from a smaller city to Tokyo is call moving “up” to Tokyo), but people seldom move downwards, do they?” And I realized that he had a point. So, the next day I decided to try taking the Keikyu line “down” to Miura Peninsula, and what I found there were wide-open vistas that were somehow nostalgic. After that, I frequently went down there to the city of Yokosuka to go to the bars. There you had American military people, you had Japanese National Defense Force people and an atmosphere that was uniquely raunchy, like one that appears in the songs by the pop star Momoe Yamaguchi. One day, I went to a bar with a three-sided counter and there was a middle-aged man sitting there. He didn’t say a word and just kept slowing drinking his cheap “lemon sour” cocktails. Something about his face captured my imagination, and I kept watching him.I had seen lots of plays by the young generation of theater makers in Tokyo’s small-theater scene, but in 2012 when company mum&gypsy’s Takahiro Fujita work won the Kishida Kunio Drama Award, I somehow felt that this was the end of a certain stage in my life. And as I thought about my future and felt the need to find something different, I suddenly thought that the answer might be in the mystery I found in the face of that man drinking alone in the bar in Yokosuka. Then I thought that it might be interesting to try to connect that face to a theatrical work. But, rather making something that people would come to see in a theater, I wondered how I could get people to go to a bar in Yokosuka. And as I was pondering that question, memories of the game books I played with as a child came suddenly to mind. I thought it would be interesting to have people walk in an actual following the choices in game book style. The result of that idea became my ENGEKI QUEST.

- What could it have been that young people of Tokyo couldn’t find in the small-theater scene but could find in the face of a middle-aged man drinking alone?

- When I was in Tokyo and writing things for magazines or websites, I always felt something lacking, in the sense that it wouldn’t leave any type of accumulated value in that locality. I believe that there has been a time when “grasses without roots” grew and came to flower in Tokyo, and I did actually feel the passion on the small-theater scene. But gradually, I began to feel that more and more people were just working within an already established set of systems and rules. Pioneers like Toshiki Okada and Junnosuke Tada created a new world of theater works that had no rules or systems. I had sensed the pressing need they had to create such works, because if they didn’t there would be no world for them to live in. But gradually, there became an increasingly strong trend toward simply seeking new forms of expression. It is the kind of trend you could expect in Tokyo. Perhaps there is a pressing need and possibilities for the future in that as well. But I felt that I didn’t want to bet my life on that quest.

Then the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami struck, and I felt that there was no more reason to stay in Tokyo, so I moved to Yokohama. It was only a move of 30 or 40 kilometer, but it was a big decision to make. Then, when I was thinking about where and with whom I should start to build a new life, that was the time that I encountered that middle-aged man drinking in Yokosuka. It is difficult for me to put into words what it was that I saw in that face, but I thought that I wanted to face that question with all that I had experienced and built up until then. It may be that I could have found that kind of face in a slum in the Philippines or on a bus or a market in China.

Adventure Book (adventure game scenario) adopting the game book format

- Your “ Adventure Book ,” is a new form based on the game book format. Why did game books become the method you chose to take audience out into the town to search for things like middle-aged man’s face you discovered?

-

Since quite a while ago, I had the idea that I wanted to write a game book. Because they were what I loved as a child and read over and over until they were worn and tattered. But, with my ENGEKI QUEST I have drawn from other forms besides the game book as well. Especially, they are philosopher Walter Benjamin’s “Arcades Project” and architect Christopher Alexander’s book “A Pattern Language.” Both of these books are made of literary fragments that don’t run from introduction and development to a conclusion or any story-like narrative. I have always longed to create things in that type of form that consist only of lumps of text with no storyline or conclusion. For example, one might use a case like the face of the middle-aged Yokosuka man as a subject and possibly develop a wonderful story around it that would delight an audience. But that makes the audience a passive entity that simply “consumes” the story. That is not what I want to do. My idea is that, if I create something that remains unconnected lumps of text that never link together into a single storyline, couldn’t I take advantage of the individual perceptions of each member of the audience and bring out their potential to become active creators rather than passive consumers? It may be that these separate, unlinked lumps of text may not create a story that people can grasp, but I thought that if they were put in the form of a game book, perhaps they could function effectively.

- As an art form, I think your ENGEKI QUEST is something that has brought a dramatic change to the positioning of the audience. The way you took the innately passive audience and made them active by giving them the right to take on an editorial role was revolutionary. Is it that your experience of seeing many plays in your capacity as a critic gave you doubts and questions about the way audiences are positioned.

- Those doubts and questioning were indeed very strong. When the traditional “theater” or plays are used only within the scope of the traditional system and rules, the audience will inevitably take on a passive role. Human beings should naturally have tremendous potential, but the moment the become an “audience” they become passive consumers who think, “I paid money to see this, so I want to be satisfied.” And on the theater-makers’ side as well, they are tempted to fall into the role of ones willing to give the audience the satisfying service they want. That relationship of the two parties is a very limited one I believe, a closed prospect. Isn’t that estimating people’s potential at too low a level? I want to look more positively at the audience’s potential. That is a big motivating factor for me in making ENGEKI QUEST works.

- For the young generation that is used to playing role-playing games on a daily basis and using the Internet social media where everyone is both sender and receiver, it will only become an increasingly important question how we present the arts to them. Do you feel that your work is now opening a new circuit for communicating the enjoyment that theater can bring?

- The very foundation of ENGEKI QUEST is a belief in the power of the audience. And I also want to believe in the future that today’s young people will build. That is where the real hope lies. But, I have doubts about an attitude that trusting completely in the sensibilities of the young is the answer. I don’t want to criticize young people, but I believe that there is always a need to look critically at the environment that young people are being surrounded with. For example, in the case of the social media, to what degree do people really have the right to send and receive messages independently, and where the editorial rights lie? There is convenience and a sense of cleanness in the image of the internet as a place where you can get any information you want, but isn’t there also a rather dangerous tendency to think that “everything is right here” and to not see the things that should and do exist outside? That is where I feel the presence of an “invisible wall.” I would be fine if everyone present in that internet world were happy, but unfortunately that is not the case. In fact, there is a tendency not only in Japan but also in places like South Korea for many young people to live enclosed within its “walls.” That is what makes me feel that I want to throw some stones of my own against those walls.

- For people who think there is no need to see the world that is not right here in front of their eyes, what do you think can be done to make them look farther?

- For example, if you live in Tokyo, you don’t have to see the face of that man in Yokosuka, and it is as if he doesn’t exist. I am thinking that with ENGEKI QUEST it can be possible to bring that outside world to them in a rather easy and acrobatic way. Lately, one thing I am trying to do is to make my works as game-like as possible. So, on the surface they mimic games and are thus easier to get into for more people. But, once they start playing, I would like for them to gradually realize that in fact it is not only a game but also art.

- Would you tell us in a little more detail about what it is that you want to show people through ENGEKI QUEST?

- For example, right now, at the request of the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University I am creating “ENGEKI QUEST – Escaping the Flower that is Tokyo Version” that takes Tokyo as its field. Tokyo is a strange place. Few metropolitan areas in the world are as immense, and different people have very different images of it. So, how do you perceive Tokyo?

Right behind Waseda University is the terminal where Toden Arakawa line begins, so I chose stations along the Toden line as the stage for this ENGEKI QUEST version. Along the Toden line there are many different views of Tokyo’s giant new symbol, the Sky Tree broadcasting tower. Tokyo will host the Olympics and Paralympics in 2020, and for this and other reasons the city is changing. How do the people who participate in ENGEKI QUEST view these coming changes? From the last station on the Toden line at Minowabashi Station, you can probably walk to Sanya, a district where manual laborers gather for day work. Many of the people living in Sanya today were young laborers who were brought in groups to work in Tokyo at its time of transition half a century ago when the city was preparing to host the first Tokyo Olympics and would work to build the metropolis of Tokyo we see today. For various reasons, eventually many of them were never able to return to their hometowns and grew old living here. Recently these old residents have been joined by an influx of young homeless people. Although the way different people will perceive today’s town of Sanya, its existence is an undeniable truth of today’s Tokyo. Nonetheless, people who participate in ENGEKI QUEST – Escaping the Flower that is Tokyo Version are free to choose whether they take the walk to Sanya or not. It is not the case that I want force the participants to look at the reality that is Sanya. As for Sanya, I want to show that it is a part of this world and one among the many places labeled “You are here” and that it is another of the countless choices that people can make to meet the rich diversity of people that live in this world.

The creative process for an ENGEKI QUEST

- Could you tell us in some detail about the process by which the information you gather from your research is then worked into what you call the Adventure Book?

-

Whether it is in Japan or overseas, the local collaborators who work together with you on the particular project are very important. The first thing is to decide the area that the Adventure Book will be staged for. Sometimes the area is decided by the producer that requests that a project (ENGEKI QUEST) be staged in their area, and in that case as well the first thing to do is to think about and decide the scope or size of the area to be involved. Once that scope is roughly decided, the next think is just to walk and walk around in that area exploring it. As we walk we do interviews with certain people and in certain places and try to talk with as many different types of people as possible to gather stories about the area’s history and interesting episodes that have taken place there. The length of this research stage can vary by case, but I take at least three weeks as the standard. And while we are doing this fieldwork we also gather as much written reference material as possible to study. If something catches your attention as you are walking, you do research on it, and when something catches your imagination as you are researching, you go there to see the site. So it is a repetition of this cycle of searching and learning. During this research stage I refrain from deciding on a theme for the project.

- Then do you go about editing the information you find in the research stage?

- Since the final editing rights are left up to the participants/audience, the first thing we need to find is things that will motivate them to want to play the game, to walk the area, so I start working on a structure that will provide an enticing entrance for them. In the case of the Hong Kong project, I got my inspiration from a project call “Culture Masseur” that I had participated in and then adopted a style for my project that had a mysterious masseur leading the participants around. Then I chose a provisional starting point and goal, and then it was just a process of connecting those two points with interesting spots. And sometime a theme will reveal itself during this editorial process.

- What kinds of information do you work into the Adventure Book script to guide an ENGEKI QUEST?

- Basically, the text is made up of simple directions like “Go to the right” or “Go to place such-and-such.” The more research you do the stronger the desire becomes to work more of the things that have come out in your research, but lately I try to cut out as much of that knowledge and information as I can. What is more important is to try to inspire the participants’ to use their imagination so that the will discover and feel things with their own senses. The only purpose of the Adventure Book script is to stimulate the participants’ own abilities. For example, even if there is a scene where having the participants turn to the right at a certain point that will open up a wonderful vista for them to discover, that view may not be describe in the Adventure Book script. If you go there you will see it yourself, so there is no need to describe it in the text. It is enough to just write “Turn to the right” and then just add a few sentences that stir the reader’s curiosity. Or, if there is an interesting coffeehouse in the vicinity, I might write a few words to encourage the participant to check it out. But you still leave the choice of whether to enter it or not up to the individual. When someone participates in an ENGEKI QUEST, I want to do something to rewrite the map in the person’s mind and I am hoping that they will meet different kinds of people through the experience, but the right timing for such encounters will be different with each individual.

In any event, this new Adventure Book style of script that is different from a novel or a play is still in the developmental stage. Overseas, the current state of things is that I ask the overseas collaborators to cooperate in the research stage, after which I will write the final text, but when doing a project in Japan, I have begun to put together a team of writers to write a script together. In that way, it brings in perspectives and vocabulary that are different from mine, and I feel that leaving parts up to different writers is an ideal form for an ENGEKI QUEST.

Encountering unimagined audience/protagonists

- You spoke earlier about not underestimating the potential of the members of the audience. Would you tell us a little more about your views on the audience as a presence?

- When I did my first ENGEKI QUEST for blanClass, what I discovered was that once the participants set out into the field of the quest, you will never know what to expect from them (laughs). For that quest we had arranged for professional actors and dancers to be performing along the course, but once it started it was full of unexpected results, and the audience moved in ways that were completely beyond anything I had imagined. At the end of that day, we planned to have all the participants return to blanClass for an after-event talk, but many of them didn’t come back. It turned out that a group of participants who were meeting each other for the first time at a restaurant on Miura Peninsula that specialized in simmered giblets the was mentioned in the Adventure Book script suddenly got friendly and started to have an extended eating and drinking party there. I though that kind of completely unexpected happening was a lot of fun to see. For that reason I gradually began to put fewer and fewer restrictions that would control their realm actions, and I began to think about ways that would actually encourage the participants to change the course of the quest’s development.

- One of the interesting things about an ENGEKI QUEST is that every participating “protagonist” comes away with a different experience. Is there some format that enables participants to share what they have experienced?

-

There are mainly two types of ENGEKI QUESTs. There is the “performance type” that is done on a limited schedule of a few days at a festival and the like, and there is the “display type” that is set up on a more permanent basis with the Adventure Book script placed where anyone can take one and follow it as they please. As for feedback from the participants, in the performance type we arrange a place where the participants can gather to talk about their experiences after the performances are over. With the display type, we use hashtags to allow participants to post comments about their experience on the social networks, and sometimes talk events are organized later on. For example, with the ENGEKI QUEST we did in Hong Kong, we arranged a time at the end of each day after the event for participants to give feedback. In fact, when we talked with the Hong Kong participants, they brought out one thing after another that they had experienced, so the feedback times were very stimulating.Thanks to these conversations, I felt that ENGEKI QUEST can function as a new type of platform for discussion. In Hong Kong, the people’s mother tongue is Cantonese, but many of them also get English education and are also educated in standard Chinese. The people that come to art events share a desire to preserve the established values and culture of the intellectual society, and at the same time they have misgivings about the rapid changes taking place in Hong Kong today. I felt that, depending on what input we provided in an ENGEKI QUEST, we could strike a cord with the inner misgivings of these people and get a significant response.

- In other words, you could choose to work in experiences that would stimulate discussion and positive discourse?

- Yes. But of course positive discourse is not an easy thing to achieve. For example, if someone has a particular ideology that they believe to be the truth and righteous, that truth will probably be a strong force in their life. Unfortunately, however, in today’s post-truth age, people tend to only believe what they themselves believe in and are not motivated to go beyond the invisible wall that separates them from others and become involved with people who are different from them. So, discourse is difficult. Especially in Asia, each region has a mix of people with different cultural backbones, so mutual understanding is difficult. But, I am very interested in this chaotic state that exists in Asia. There is never a single answer that will solve a problem. That is why it is necessary to start from discourse. As an approach to this state of chaos, rather than going in with a firm methodology or prior knowledge, I want to begin by walking the actual localities and listen to what the people there say. It is important that we don’t go in with a determined set of values.

Since I am also a theater critic, when I watch theater I tend to make judgments based on the aesthetic values I have acquired, but if I try to make judgments that way, I don’t think I would be able to understand the theatrical traditions of, for example, the Philippines or China. Japanese critics are used to the aesthetic values that that have filtered in from the West, so I don’t thing that looking at Asian theater through glasses tinted in the color will lead to any understanding of its real meaning, and it could lead to the decision that it is all simple outdated. If you are going to try to understand Asian theater, you at least have to begin by looking at the cultural and social backgrounds that led to their unique forms of expression. For example, in Shanghai, where there is always the need to deal with censorship, there is a lot of performance being done now under the wing of art museum educational outreach programs. If you are going to present works as “theater” you first of all have to submit the scripts to the censors and get approval for them. But that censorship process doesn’t apply if you do it as a performance at an art museum. So, there are artists in the performing arts in Shanghai who use the art museums as a path to avoid censorship while experimenting with new forms of expression. They are clever, but they rarely flaunt that cleverness in their artistic activities. Because the things they are doing could easily be censored. The performance being done in Shanghai is of the type that might be called forceful. But that might be part of the strategy that enables these artists to continue doing performance there. And probably, this is the kind of complex situation that is difficult to understand unless you are able to let go of your preconceptions.

Activities Overseas

- Up until now, you have done projects overseas in Manila, Dusseldorf, Ansan (South Korea), Shanghai and Hong Kong. What are the things you focus on when doing ENGEKI QUEST projects in foreign cities with different languages and cultural backgrounds?

-

The working method is always the same. I want to walk the towns and eat and drink with the local people (laughs). However, my collaborative connections are completely different in each locality, so I think about strategies of how to find them. I try not to use taxis as much as possible and ride the local public transportation instead. It may be buses or trams or bicycle taxis; and in that way I physically experience the flow of the cities. I try to grasp a feeling of the way the city lives and breathes. Today, community art is an important issue throughout the world. In many places in Asia as well, people are working on the issue of what can be done for the society and the communities with art. In other words, there are people everywhere who want to get out of the theater or the art museum and do things [artistic] outdoors. It seems that people find the ENGEKI QUEST format to be one that can be used to get in out touch with the society and the communities, and I feel that is why they ask me to come and do a project in their town.

- So it seems that the game book can be an effective medium for creating meaningful contact between people and the city, between people and the communities, be it in Asia or in Europe. What are your thoughts about that potential?

- When I interviewed Thailand’s Thanapol Virulhakul (a writer, choreographer, director and dancer who creates dance works with an anti-authoritarian social message) about the activities of the Democrazy Theatre Studio that he co-directs, he told me that he uses game aspects in his theater-making as a strategy for dealing with censorship. He also said that for people who normally look at the art world as something distant and hard to enter or associate with, he finds a game format to be an easy and effective way to get them involved and participating in art projects. In that sense, the game book format may be one that is easy to adopt in many different countries and regions.

What I felt from talking about my ENGEKI QUEST projects with curators and producers from around the world at an international meeting venue of the performing arts like TPAM is that they are interested in the game format as one that combines playfulness and simplicity with a potential for complexity as well. Things are especially difficult for people trying to deal with communities. Unlike presenting works in a theater, when dealing with a variety of communities, you have to get outside and away from that [theater] realm that is protected by the established concepts of art. But that isn’t an easy thing to do. That is because you have to communicate and deal with people who don’t share the same common language. In that case, games with their simple structure can provide a platform for building a common language. It is like the case of mah-jong that I cited at the beginning, if you are standing in the same [game] arena, you may find you are able to interact and communicate on the same level, regardless of differences in individual affiliations, positions or ideology.

New Projects since ENGEKI QUEST and ambitions for future

- Finally, I would like to ask you to tell us a bit about the projects you have undertaken after establishing your ENGEKI QUEST projects. At the 2018 Taipei Arts Festival in Taiwan, you presented a work titled IsLand Bar, and we hear that now you are at work writing a play titled HONEYMOON.

-

The city of Taipei is now involved in setting up a number of new performing arts platforms that have succeeded in attracting a considerable amount of attention among producers based in Asia, and my aim was to give them something they were not expecting, in a positive sense. Currently, there is a market for performing arts that is taking shape in the countries of Asia, and this is accompanied by rush of construction projects for new theaters and art museums, but the foundation for these projects seems unstable to the extent that there is an air of a potential economic bubble forming. That in itself can be seen as an interesting development, but we have to also consider whether or not simply being drawn into this market will be a good thing for the artists in the long run. Last year, it was a personal shock when my same generation’s theater-maker Noriyuki Kiguchi (a theater director, playwright and art performer active internationally before his death from lung cancer in 2017 at the age of 42) and his producer Takio Okamura both passed away. I realized that it is only by chance that they have died and I am still living. I started to think, how I and other artists will survive in this chaotic world of ours. As for myself, I want to build a place where I can live as easily as possible and enjoy the life I have. I also want to do what I can to make the relationships between artists, audiences, critics, producers, technicians theaters and festivals better than they are now. That is the idea behind the work IsLand Bar that I presented as an attempt to create a new relationship between artists and audiences in Taipei. I had 12 international artists join a performance project set up like a bar, with each of them having a table as a form of island where original cocktails created as allegories for different political or historical issues were served while they talked to the visitors (audience) that came to sit with them. My grandmother on my father’s side was born in Kaohsiung, Taiwan when the island was colonized by Japan (before WWII), and I made that the subject of conversation at my table during the performance, and the result was that it became a stimulus that revealed the complexity of the identity of the people of Taiwan. And every evening after the performance, I made the square in front of the hotel where we were staying a “secret gathering place” where the artists and the audience could gather and talk without and unnecessary barriers between the two groups.

- So that also became an extension of the project that fostered conversation, didn’t it? We are told about another project titled HONEYMOON that you began in 2017 under a grant as a Saison Foundation Senior Fellow. What was the concept behind this work?

- My ENGEKI QUEST projects are each based in a particular area, and there are many local episodes that are revealed in the course of that locality’s research that can’t eventually appear in the Adventure Book script, and I have accumulated a large number of these in my mind. Especially, one of these recurring subjects that stands out in my mind is the movements and migration of peoples. And as an extension, a result of my search for a different format to give expression to this subject, I created HONEYMOON. I recently got married, and as supposed “honeymoon” I did a research trip. When I learned that my grandmother on my mother’s side had once worked as for the Southern Manchuria Railway, I made a trip tracing my grandmother’s trail through the region from the Korean Peninsula up into Manchuria. The recent work “HONEYMOON” is an attempt to put the severe reality I found there into a work in the format of a play. This work is in part a compilation of my thoughts about what a play actually is, and at the same time it is an attempt to grasp the geographical history of the country Japan. I am still examining whether or not the format of drama or a play is the right one for this.

Since I have already established to some degree my methodology for creating ENGEKI QUEST and for writing as a critic, so perhaps It would be safer and easier for me to stick to these formats. But, as long as I am interested in people’s individual potential, I don’t want to confine myself to these frameworks. I want to continue to pioneer new, unknown methods. I want to pursue [artistically] the appeal and the awesome severity of drama. In the format that we call drama, there is a wonderful and unique potential in the nature of this powerful art form that can gather people to see a play performed. And I really believe that this wonderful and unique art form will go on to be more necessary than ever, in Japan and in the world. That is, as long as there are no unimaginable new technologies developed…. Perhaps we can say that the day when theater is no longer necessary is the day when we stop being humans. I want to continue to explore the nature of theater and drama with its unique power to fascinate and move the human heart and mind.

ENGEKI QUEST – Tokyo Exile

photo provided by 冨田粥ENGEKI QUEST – The Port Detectives and 11 stories

Directed by Takayuki Fukada

ENGEKI QUEST – The Rainbow Masseur

(2018/Hong Kong)

photo provided by Hong Kong Arts Center

ENGEKI QUEST – Liebende in Düsseldorf

(2016/Düsseldorf)

Photo: Christian Herrmann

IsLand Bar

(Taipei Art Festival 2018)

(C) Gelée Lai

Related Tags