Leading up to a Theater Career

- Would you begin by telling us about how you first got involved in theater?

- It began when I joined the “filmmaking and theater club” at my high school. From the time I was in elementary and middle school, I had thought that I would like to make movies, and I joined our high school’s club because it had filmmaking in its name, but it turned out to be only a theater club [laughs]. It was just your typical high school drama club, and since it was uncomfortable for me just participating in it in the usual way, I decided that it would be more interesting if I wrote my own plays. And when I did, I even won a prize at the prefectural drama club contest.

- What made you think that you wanted to make films?

- I was rather sickly as a child and I had to visit the hospital often, and I hated getting shots. When I took my shots bravely, my mother would reward me by letting me rent a movie at the video rental shop. I began from watching the old famous movies by Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. I loved comedy, especially Chaplin, and when I read his life story, I thought it was so cool the way he rose from poverty to become a success, and learning about the background behind his comedy was a real surprise and inspiration for me. But, since I was only watching these films at home on video, I have a bit of a complex regarding people who insisted that films have to be seen in a movie theater to really appreciate them. Also, my grandfather was the representative of a photography club in Yamanashi and was the kind of person who also played classical guitar and had a large collection of records and CDs and like listening to jazz music. And, I think that influence also had a considerable effect on me.

- Were there any artists in theater or film that particularly influenced you?

- I really loved Minoru Betsuyaku, and also the movie director Woody Allen. In his early comedy film Annie Hall where Woody Allen plays the comedian Alvy Singer, I thought it was very interesting the way he appears in a scene of recollection from his childhood. I feel that influences like that are present in the way I make theater today.

- For college you went to Oberlin University, where Oriza Hirata was an instructor in theater. Did you plan to continue theater when you went there?

- Since I wanted to make films, I was naturally thinking of going to an art university, but I was swayed when the girl I was dating at the time said she would try to go to the same university as me. As I was debating what to do, the teacher in charge of our high school drama club suggested that I go to Oberlin University because theater instructor there was Oriza Hirata. That was the first time I had heard of Oriza-san, but when I read his scripts and books they were interesting, so I decided to go there. But, it turned out that Oriza-san had just moved to Osaka University, so I ended up in the wrong university [laughs].

- He moved to Osaka University in April of 2006, so it was just when you entered Oberlin, wasn’t it. So, weren’t you planning to do film then?

- Being young and conceited, I thought that if I really wanted to do film I would have the chance someday. There is always the path of a self-taught artist as well, so for the time being I thought I would study theater, which I didn’t really know much about yet.

Starting Hanchu-Yuei with the aim of making a creator group

- In 2007, the year after you entered university, you started a theater company. Why was that?

- Since Oriza-san was no longer at our university, I decided that I would have to learn by myself, in practice. So, I invited all of the people I became friends with and before long we got together a company. The college students at the time were into units and production aimed at performances, and there weren’t many who were starting theater companies. I thought that wasn’t a good way to learn and train people for a future in theater and that it wasn’t a good way to help your art mature. Also, at the time the influence of Oriza-san was so strong that all of the students at the university doing theater at the time were doing his style of contemporary colloquial conversation type plays. But, I had the vague feeling that it wasn’t good to have everyone doing the same thing, so I was trying to do different things.

- There is Takahiro Fujita, who was two years your senior at Oberlin, and in the same year 2007 he started Mum and Gypsy, which is not really a theater company but a unit with no set group of actors or staff.

- Yes. But, rather than saying mine was a theater company with a pyramid structure with a playwright and actors, I wanted us to be a kind of cooperative where everyone was a creator with their own individual talents. So, I wanted to call it a group rather than a company.

- In 2010, Kazuki Takakura joined your group. He was from Tokyo Zokei University, wasn’t he?

- Yes. Actually, in 2009 a large number of the group I had been working with [graduated and] got jobs. I had told them that if they wanted to get regular jobs, they should do so. In the end, as soon as we all graduated it changed from a creator group to a production unit, although it wasn’t what I had hoped for. Around that time, a friend of mine at Tokyo Zokei University who had done a performance leaflet for me introduced me to Takakura, and when I went to see his graduation exhibition, I thought there was something very drama-like (theatrical) about his works. The gist of it was that he had prepared a bunch of different weapons and there was a sign that said, “Chose one of the weapons and take a pose in front of the video camera.” In short, it was a work that had people pose as a “warrior hero” in front of the camera, and the fact that it was video and the people could move their bodies as they posed struck me as theatrical and very interesting. The idea was so enticing that I also took a weapon and made my pose. But, then you find out that the camera wasn’t filming and you realized that you have been tricked by your own vanity! I thought it was great, so I took one of his calling cards from the pile and contacted him afterwards.

- Did that then lead you to being working together immediately?

- It did. Takakura was also thinking that he wanted to do something beyond the traditional fine arts relationship of “art works and viewers,” and it seems that he had already realized that the next step for him was theater. Because his eyes were on something “between” (connecting) the work and the viewer, something you might call movement, or a live aspect, or audience participation, that kind of moving aspect. So, we were talking on the same wavelength from the beginning. What’s more, we also happened to be from the same town. We had a lot in common, and before we knew it we were working together.

- Were the character costumes and the stage art for your first work Takakura’s designs?

- Yes. His specialty is forms of expression like dot-picture games, and from the beginning he had a style that went toward things that were somehow familiar, pop and nostalgic.

- In what way was Takakura involved in your creative process.

- It was rather difficult before we settled into our current working method. At first, we’d have him do everything he wanted to do for the stage art and then I would try my best to use it as it was, but it was hard to get it to come together with a good balance as a total work. For example, with the stage art, if he said some place was going to be red, when the audience eyes would always go there and not follow the actors. That is something you only realize once it is in place in the actual theater. So, I realized that a balance had to be reached.

- Originally, was your working method one of collaborative creation, or did you personally create an overall plan to begin with?

- I want to write a proper script and have it remain as a play in its written form. So, Takakura’s role was as stage art director, and lately he also does things like the advertising art and thinks about the visual presentation of Hanchu-Yuei.

- What was the first play for which you thought the respective contributions of your creator group all came together well?

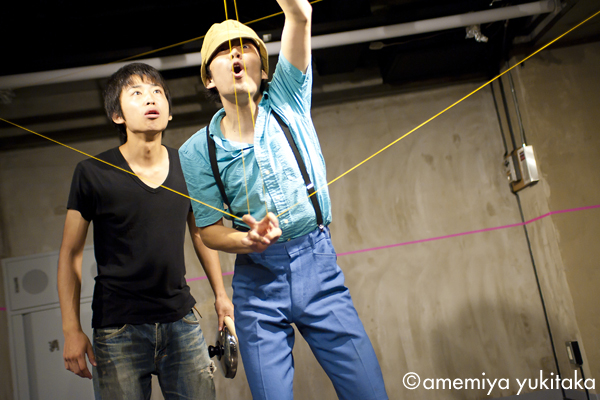

- It was “Hanchu-Yuei no Uchu Boken-ki 3D” (Hanchi-Yuei’s Space Adventure Story 3D, 2011). It was composed of an exhibition and play, and for the play, Takakura played a less active part in the stage art and the entire production had a good pulse and flow.

- How do you work with the actors?

- What I always tell the actors is that I don’t want them to think that their role and purpose is to act. Since there are things that you can’t know unless you have experienced the difficult struggle of creating a work, I want to talk to them from the standpoint of mutual respect as creators. For example, Sachiro Nomoto also makes films, Kazuki Ohashi does Nihon Buyo (traditional Japanese dance) and Fumi Kumakawa does things like making jewelry and accessories. I want a situation like this where all of the actors of Hanchu-Yuei have another face as creators in their own right. So, I often talk with them about things not related to theater, such as art that I went to see and was glad I did. That is the kind of relationships I want to build, and I feel that to some degree I have succeeded in that respect.

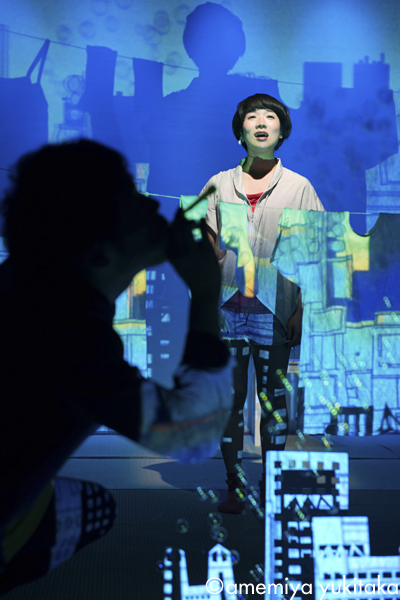

Exploring the possibilities of theater with superimposed text in “Girl X”

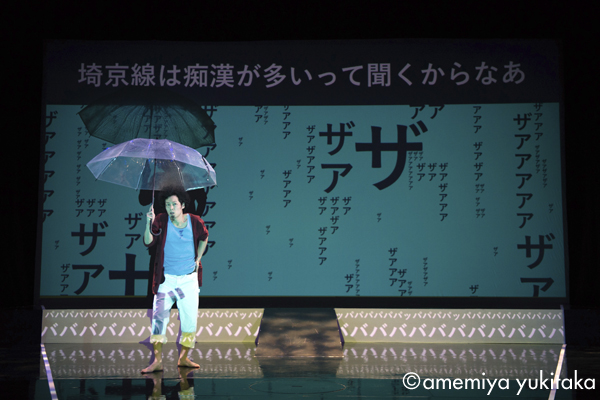

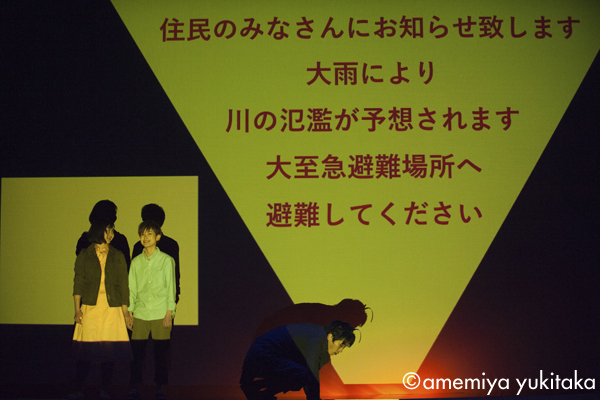

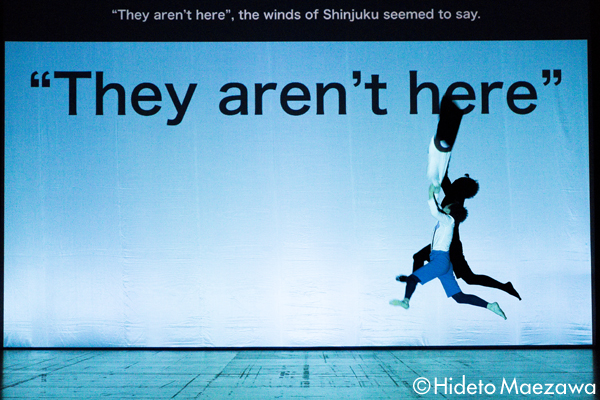

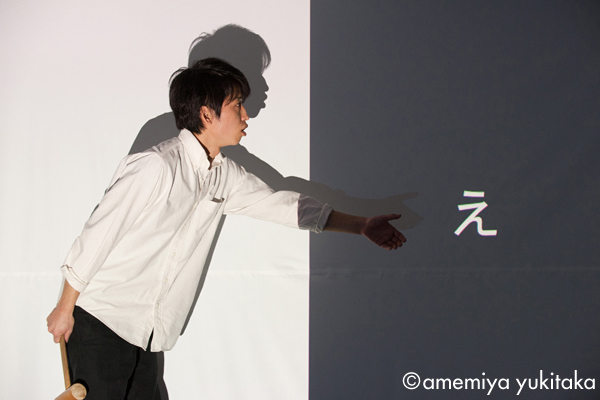

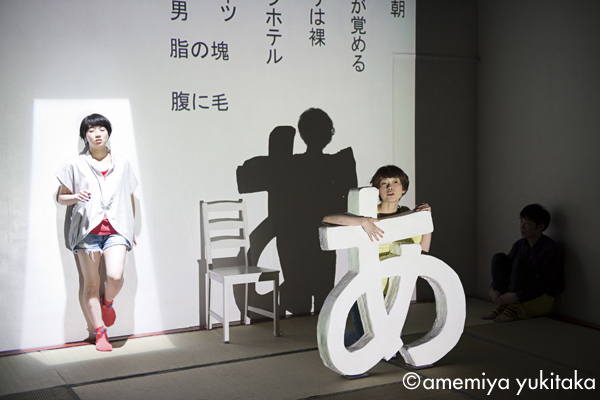

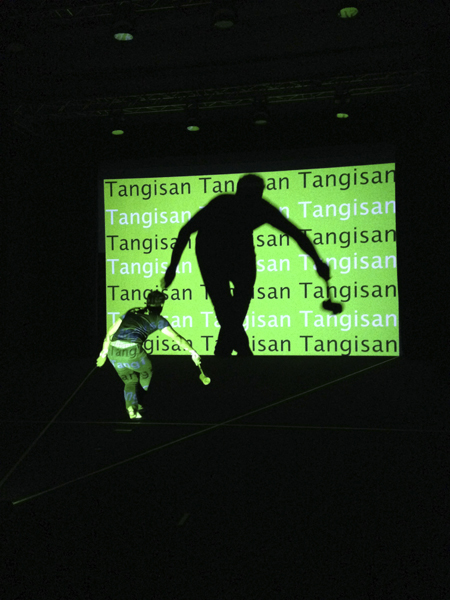

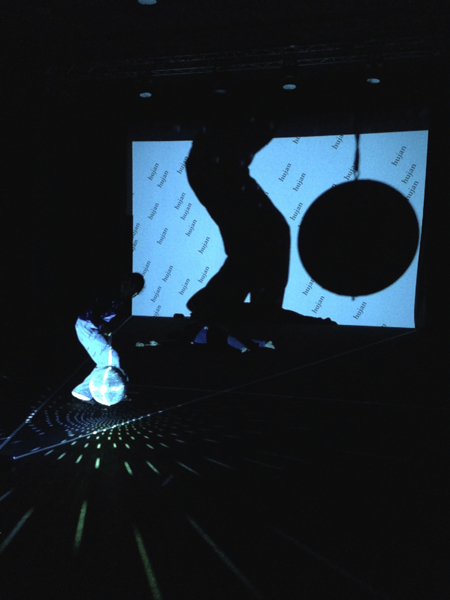

- In February 2013, you presented the premiere of “Girl X” (Yojo X) as part of the work “Hanchu-Yuei Ten – Yojo X no Jinsei de Ichiban Tanoshii Sujikan” (Hanchu-Yuei Exhibition – the most enjoyable few hours in the life of Girl X). Within the appearance of an exhibition, the first half has you (Yamamoto) performing the solo play “Tanishii Jikan” (Enjoyable time) and the second half is the play “Girl X” (length of about 60 minutes). “Girl X” was a revolutionary play that is played out by interaction between two male actors on stage and the words (script lines) of non-appearing characters that are projected on the stage background. The play is set in Tokyo in the year 2013, at a time when a series of rape-murders of young girls has been occurring. The male actors play the roles of “Man” (a sister-character’s former boyfriend), the sister’s “Younger brother” and “Sister’s husband,” while the other characters in the story never appear on stage but are represented by their script lines projected in text form on the background of the stage from a projector positioned in the audience area. The layered exposure of the text has the appearance of subtitles superimposed on the film of a movie as the story proceeds. What’s more, variance in the size and shapes of the letters of the text, as well as their movement, are used to express the feelings of the non-appearing (off-stage) characters whose spoken lines they represent. What led you to change to this completely different kind of style from what you had used previously?

- I have often had the experience of writing a play and thinking the words, the lines, I have written are good, only to be disappointed in the way they sound when I have the actors actually recite them. I thought it might be that the words were wrong, due to my lack of imagination, but when I look at the words on paper, I feel that the flow isn’t bad. So, I kept wondering why they were no good when read out loud, I couldn’t find the reason. At one point I gave up and tried rewriting the lines in a colloquial-speech drama style of conversational-drama style so they would sound better. The play I took this rewriting process to an extreme with was “Tokyo America” (2008 premiere, 2012 restaging). The setting of the play is rehearsals for a theater production, with the director calling out “Stop,” from time to time—in other words it is a backstage drama. Within this style, I left the [script] lines of the play-within-the-play as they were, meaning the way I had originally written them that didn’t sound good when spoken. With this, I thought I had solved the problem in my mind. But, I was still left with the frustration of knowing that the words (lines) as I had originally written them were not successful as a stage script. So, I kept wondering what to do. Since the original words/lines of the script as I has written it looked good to me on paper, why couldn’t I show them as [unspoken] text and let the audience experience them that way, and as I thought about how to do that, I arrived at the idea of projecting them as text on stage. What made me arrive at that idea may well have been my experiences of reading subtitles in movies. Besides words for the ears, there can also be words for the eye. Because the amount of information the audience receives through words for the ear is greater than words of the eye, the latter have greater potential to be expanded in the imagination.

- In short, words for the ear have the added aspect the voice as a physical manifestation of the actor, but with words for the eye leave the viewer free to imagine whose voice speaks them and what is the emotion they are spoken with. That is what you are saying, isn’t it?

- Yes. I was looking forward to what the audience would feel and what it would evoke in their imagination when words are suddenly projected on stage. What led to this approach was the experience I had going a workshop for the [theater] staff at Oberlin University in May of 2012. The idea I got for the workshop was to pose the question of whether or not there could be theater without a single actor. There is a table and chairs, and when there is for example a slight change in angle of the lighting or movement of a prop, or at one moment a screw falls from above, or a light suddenly shines on them, is it possible to make drama/theater purely from such elements [without actors]? That is what I had the students think with me about. Then I added one more element by using words, projecting them as script on the stage. Even though no actors appear, projecting a line of script on a chair, having the chair move was enough to cause a mental state to arise, to come into view. I felt something tangible and valuable in this experience. Then, it was with “Tokyo Fukubukuro” event at the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre that I used this method in a Hanchu-Yuei production for the first time.

- What was the work you performed at Tokyo Fukubukuro?

- Since I thought of having words appear as a divine act, I chose the metaphor of “A bored god playing with humans,” and made it a play in which the humans had to obey the words and images that appeared before them. In other words, it was a situation in which the humans were manipulated by the words. Be it [man and woman] “dating” or “breaking up,” the words were obeyed, as if being manipulated by the gods.

- Toshiki Okada, the leader of the chelfitsch company, although he doesn’t use words, creates “narrations” using situations and mental states, rather than conversational drama. Have you ever been influenced by that method of Okada.

- I must admit that, when the era of conversational drama began to lose popularity, I think I was encouraged to learn that conversation wasn’t an essential, that conversation wasn’t the only way to develop a story in drama. However, rather than being aware of that [Okada’s] method, it was the contents of [his] plays that I felt affinity to.

- In other words, it was because the words (scripts) you were writing were not words of conversational drama to begin with that the actors couldn’t speak them, wasn’t it?

- That’s right. It was never possible for me to make a story work as theater simply using conversation. I couldn’t make things work without some other element, like the developing scenes of a movie. So, I intentionally used both dialogue and text/words to go beyond the category of genre of drama. I believed that to be a method to expand the possibilities of expression.

- Because you are just projecting words on the stage, it is unclear who is addressing the words to whom, whose emotion it involves, or even whether it is indeed a line in the story or not.

- Yes. I feel that the words I project on stage are “recited” or “chanted” words. They are not lines spoken by an actor, they are words for the audience to recite in their heart and mind. That is my intention when I write. Therefore, in order to have the words fit the breathing [pace] of the audience’s [imagined] recitation, I always operate the projection of the [text] slides live by myself as the performance is going on. As I am projecting them, I am thinking, “Please recite at this pace, with these breaths”, and that also makes the words a pipeline that connects me to the audience.

- This concept of “words for the audience to recite/chant” is more than just interesting. I find it very moving.

- For example, if they are very peaceful words, the audience will recite them peacefully, won’t they? That is something I really want to do. What’s more, one of the reasons I want to try to do this is because it is not one person’s recitation but recitation in a live performance where there are people all around you. For example, if it is the words “I want to live,” it is no good just to have an actor recite it.

- If an actor says it, then it would need to be part of a dialogue, a reaction to another actor’s retort, such as “You are going to die.”

- Exactly! That is the problem that caused me so much discouragement when I wrote scripts, you could say. I always thought, “What is it that causes the words to go wrong?” It was very frustrating for me, because it made me feel that what I wanted to do was something that couldn’t be done in the theater or drama context.

- If you take this concept of the words as something to be recited by the audience one step further, it means that the audience, in effect, become characters in the play, doesn’t it?

- Yes, it does. And it also implies the appearance (presence) of the gods.

- How do you actually go about creating (writing) a work? Would you tell us about your creative process?

- First, I write the beginning part of the play. As I said earlier, I have to have a script to work from. Since I don’t like to work up the script from studio sessions with the actors, I write the script up properly, and if it doesn’t work when the actors try it, then I rewrite it. I work the script thoroughly until it is right.

- What style is the script in when it is finished. For example, are there notations about things like the size of the letters of the text to be projected and the movement of the text?

- Concerning the play, I only write the bare minimum of what is necessary. Regarding the words to be projected, the only things I specify are whether they are to be in bold print or not and what the font of the script (text) will be. Other than that, I only write a minimum, what is absolutely necessary. Therefore, I leave things like the size of the projected letters and how the words are moved up to the director. It was my frustration at not being able to believe in colloquial expression that led me to this [minimal] style of writing, and I have no qualms if a director who does believe in colloquial words has the actors read the projected words. That is the artistic realm of the director, and that is the intention with which I write as a playwright.

- Are there some works for which Takakura-san directs the designing of the words (characters/letters) and how they will be moved?

- There are. There are some productions for which I will do 90% of that work and others where he and I will each do about half. It is different with each case.

- As an director you have directed the use of text/words on the stage, and once you do that a lot of different expressive possibilities emerge regarding presentation of the words, such as animation, don’t they? In terms of size, color, placement, you can really do anything. What are your thoughts in this area?

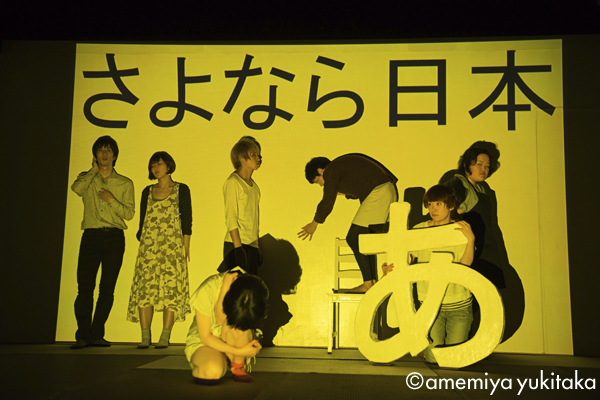

- The first time I felt that the use of words in this way had gone well was with “Girl X.” After that, I felt confident that there was a lot of expressive ways I could use words and text visually, and I tried to explore more possibilities in that area with our next production, “Sayonara Nihon – Meiso no Mama Nemuritai” (Goodbye Japan – From Meditation I Want to Drift into Sleep, 2013). But, I found as I got deeper into it that I was beginning to lose sight of what I was doing. I felt this could be very dangerous, and that I could easily lose something more important in terms of theater. So, I decided to be more austere, and now I make the visual expression of words as simple as possible.

- If your original purpose in using words was the depth of recitation, it would be meaningless is the visual expression became too dazzling, wouldn’t it?

- Yes. It would be letting the means become the end.

Information Environment and the Shaking of Moral Values

- I would like to something more about the contents of your plays. At the beginning of “Girl X” the words of a child in its mother’s womb are projected as text on the stage screen, reading, Mother, I don’t want you to be born yet, I am not ready yet to endure this rain . That came as a complete shock. The shockwave seemed to run through the whole [theater] space because of the way it captured both the weight and the lightness of living in Tokyo in 2013 after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami.

- In a word, for me as a person, it was a time when I had lost faith in what I had inside of me, so rather than look into myself, I had decided to look outward and focus myself on the society around me. And for that reason, writing Girl X was extremely difficult and painful for me. Lately, I still have difficult times, but at that time I felt like I was vomiting blood as I wrote.

- Having found a new form of expression didn’t it become easier to write?

- Probably, I had reached a point where I needed to be more honest with myself. I don’t mean to negate what I had done until then, but I feel that I had reached a point where I had to find a tool that would possibly enable me to write all that I wanted to write and a way to face more directly the things that I wanted to communicate through theater, and society and theater itself.

- What was it that you tried to face in Girl X?

- More than anything, I wanted to communicate the things I was seeing, the emotions I was seeing, the conflicts inside me and the things outside me, as honestly as I could possibly could. I felt that it was important to write these things as the 25-year-old I was at the time. I was obsessed with the belief that I had to write everything as I saw it at that moment. I wanted to cast aside any feelings of inferiority or doubt and write about the things I saw, the things I felt and the things that were happening at that time, just as I saw them.

- Among the things you write about in the 2013 Tokyo setting of the play are a series of rape-murders of young girls and men who have an abnormal interest in young girls.

- It is a question of do we have the ability to forgive such people. I don’t have an answer to this question myself. But, I asked myself if, for example, my own younger brother was a serial killer, or if a family member or relative killed someone, could you find it in yourself to forgive them? I don’t have an answer, but I thought that it would not be wrong to write a play that posed this question. I think I am questioning my own sense of values, my ethics. At the point where I realized that I couldn’t go on doing plays with characters dressed in animal costumes, I was able to take a more objective view of playwriting. When I ask, “What would I do?” I believe that this is something that will communicate with relevance to the audience.

- Since we now live in times when things beyond our imagination can occur, the old values can’t be applied, there must be a constant questioning of our challenged values.

- That’s right. In our grandparents’ era the values must have been unshakable, I believe. There was a time when every time I heard people start talking about how things were ‘in the old days,’ I wondered how they could think that way. I believe that probably, in the past, people could easily generalize because the communities they lived in were smaller than now. Our generation is more diverse and spread out. For example, I believe there was a [previous] generation that could believe all they saw on television, but now that television is no longer at the top of the media hierarchy, and newspaper are now in a shaky position, and the internet is also subject to suspicion and doubt, things are all mixed up. What reaches us on the SNS timeline is either pros or cons and also people who are lost in resignation of just being standers by, so for our generation there is really no clear values of what is evil.

- In other words, it is only our individual moral values that can put a stop to the endless perplexity?

- Yes. It can only be your own values. The fact that we no longer have any real religion may be an important factor, but really the only alternative we have is to think for ourselves and reach our own conclusions. I believe there is a universal reality in this.

- Now that our means of communication are changing, with e-mail and Twitter, etc., do you feel it is unnatural that theater makers have to base their communication solely on conversation [in plays]?

- Yes. That is what led me to use interaction between the written word [text] and people [in my plays]. In our daily lives today there is not really that much conversation with other people, is there? Because, there are few situations where we have to communicate through long conversations face to face with someone. That is why I thought it was a valid form when potudo-ru staged a play with three adjacent rooms with action going on simultaneously. If a play is going to reflect our daily lives today, you are not going to have people engaged in dialogue that goes on for 20 or 30 minutes.

- So, you want to create theater that doesn’t go out of its way to translate all communication into dialogue, and instead, is truer to our actual forms of communication today?

- Yes. I believe you could say that’s what I want to do.

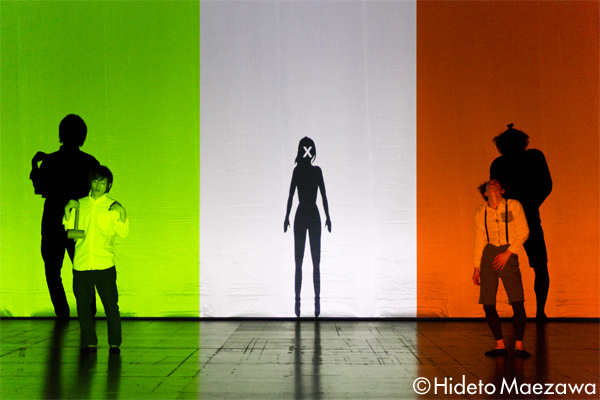

- Concerning your directing, you place a very powerful projector in the audience area and not only do you use it to project text on the stage but also on the actors, with very intense light that creates very dark shadows of them. And, the very existence of those eerie shadows on the stage seems to have meaning in itself.

- When dealing with the human form, I think it is lacking in possibilities to deal only with the flesh-and-blood body. The human shadow is part of the body and the two are inseparable. Since the shadow is an integral part of the human form, I wanted to use it as an expressive medium. There are some people who use lighting especially to disseminate the shadows when light is projected on stage art or on actors, but I can’t understand why they don’t want shadows present. I find that kind of lighting use very frustrating.

- Separating the body and the shadow and making a shadow that appears disproportionately large compared to the actor would seem to create feeling of emptiness or loneliness, rather than serving to accentuate the presence of the body.

- Creating a larger shadow serves to accentuate the smallness of a human existence. In Girl X there is a scene where we deliberately made an actor’s shadow large enough to fill the entire back screen, and our intention was to show the weakness of the human being. And, perhaps, I was unconsciously hoping that the shadow could express the dual-personality of the person. Without that shadow, the scene might not have had the effect of making the audience doubt their values, or communicate the sense of anxiety as well as it did. Perhaps I was hoping that the shadow would serve to express that sense of faltering values.

- You performed Girl X as part of the program I directed at TPAM (Tokyo Performing Arts Market) in February of 2014, and because of that performance you were invited to perform overseas.

- We premiered Girl X at a small 30-seat venue at the Shinjuku Ganka Gallery as a sort of work-in-progress, so it ended without any strong feeling of accomplishment for me. And when you invited us to perform it at TPAM while we were preparing our next work, “Sayonara Japan,” I was rather surprised, because I didn’t really feel that it was such a powerful work. I also hadn’t done the performance with any anticipation of performing abroad, and because it was performed this time in a larger space than the premiere, which gave it a different level of density, so I was worried whether or not it would communicate to everyone. But, it was particularly well received by Asian directors and we received invitations to perform in Malaysia and Thailand.

Overseas Collaborations

- Just three months after TPAM your performance in Malaysia was realized. How did that feel?

- At TPAM, Low Ngai Yuen (director of Malaysia’s Kakiseni) immediately decided to invite us to perform in Malaysia, and she was so adamant in her invitation that we agreed to go to Kuala Lumpur. And, she also decided immediately that we should stay there for a month and do a collaborative work and perform it. So I rewrote the script for Girl X with a Kuala Lumpur orientation and performed it. With the religious differences and people there being unused to things like reference to rape-murders of young girls and depictions of masturbation, it apparently was quite shocking to many people in the Malaysian audience. Malaysian people tend to be rather shy and don’t become friendly and informal as easily, so there was also something unusual for us about the feeling of distance with the Malaysian actors we worked with, and there also wasn’t much time, but I feel that I gained a lot from the experience.

- In November, you performed in Thailand and won Best Play and Best Script awards at the Bangkok Theater Festival.

- There was a lot of excitement at the Thai performance. At the after-performance talk one audience member said, “I thought this was a story of deep despair. It made me feel determined not to live like the people in the play.” But, after the talk another person came up to me and said, “She said she felt it was a story of despair, but I felt it was a purely a story of hope. I could understand the way the characters acted and I thought the events were leading them toward hope.” I thought it was great that we could get such radically different reactions from the same stage.

- After experiencing your performances in Malaysia and Thailand, what are your thoughts now about continuing to be active in Japan and the possibilities of doing work with artists from Asia or other areas of the world?

- Since we don’t receive [financial] support from anyplace, we don’t have any studio facilities and the like that we can use consistently. And, just as I was becoming painfully aware of the demerits of not having a full-time base for our activities, we were invited in this way to perform abroad and thus learned about the possibility of working abroad. I also didn’t have any reluctance about working abroad and in many ways it broadened my perspective.

- Since you are creating your works in Japanese, don’t you feel any problems with the language barrier, for example?

- Lately, I have the feeling that I should try not to do things that would be lost in translation. Previously, I never even considered such things. Of course, it was because I wasn’t thinking about such things that I was able to write Girl X as I did, but now I have gotten this new perspective to some degree.

- What are your thoughts about collaborative work with foreign artists?

- I feel that I inherently like collaborative work. Since, as I said earlier, Hanchu-Yuei was originally started with the image of a group of independent creators, what we have been doing is collaborative work from the beginning. When we worked with Ayam Fared in Malaysia, and with the collaborative project to work with Thanapol Virulhakul in Thailand from January 2015, I really had no reluctance whatsoever, though I don’t know why. I don’t speak English fluently, but I don’t think the language barrier is an insurmountable obstacle. If there is a language barrier, it creates a unique situation and relationship, which can then lead to a unique work, and if it is possible to talk extensively, I believe it can lead to the creation of a different work as a result. In any event, the type of relationship involved in a collaborative work is always a unique, one-of-a-kind opportunity anyway. At present, I think that, because I am Japanese, there are unique things that I can create.

- What are your plans for your collaborative work with Tam-san?

- TAM is a dancer, choreographer and playwright with a group called Democrazy. He is an artist who is concerned about issues in Thai society and suppression of freedom of speech, which is expressed in his works. I also have to be thinking constantly in some sense about the social issues of Japan, and in that sense I feel that we share common concerns. Although the core of Girl X will not change, I believe that the contents will change dramatically. Because our collaborative work will be performed in both Thailand and Japan, I think w will have to make it a work that can stand up in the face of the differing perspectives of the two audiences. It will be a project that will have important implications for me for the future.

- Would you tell us in a word what you think about Japan.

- When I want to bring it down to one word, when I feel despair coming on, I always go to Shinjuku. That’s because when I go there, I feel what a small thing my personal despair really is, and what a big and diverse place Japan is. Even when I feel frustrated with Japan and feel that it has hurt me, I still know that it is only Japan, not Malaysia or Thailand or anywhere else, that can heal me. That’s why Japan is both a poison and a cure for me. In that sense, I feel that it is a bond that can never be broken.