- Kakiseni started as a network platform ( kakiseni.com ) for the artists in Malaysia to exchange ideas, and today it has many programs such as Boh Cameronian Arts Awards, the Kakiseni Arts Exchange program, the KakiSENI Festival presenting a broad range of arts from Malaysia and abroad and the Kakiseni Grant program. You have been leading Kakiseni since 2009 as its second director. Can we start from what Kakiseni is and how you got started?

- Kakiseni is wordplay. “Kaki” means “foot” and “Seni” means “art”. In Malaysia, in the Malay language, when you attach something with the feet, it means that you’re really into it. If you say you’re Kaki Makan, which is food, it means you love to eat. When we say you are Kakiseni, it means that you’re really into the arts, it’s almost like saying you’re addicted to the arts.

Kakiseni was established in 2001 by two founders, Kathy Rowland and Jenny Daneels. It started primarily as an online platform where artists themselves can pool together to have conversations, as at that time so many things were happening on the scene but people didn’t have a place to talk. This was early in the year 2000, so it means everybody was just beginning to sit in front of the computer and to express themselves through blogs. Kakiseni was also the platform that started creating a database of artists, directors, and producers, so that you could just go to kakiseni.com and be connected. It was a very important marketing tool for artists as well at that point in time.

In 2008, it was announced that Kakiseni would be closed, as Kathy and Jenny were leaving Malaysia, and it seemed not relevant to run and organize a platform from afar. When I heard about the closure I thought that it was such a pity because it had been there for years, and has been working to establish a lot of artists’ careers. So we became some of the people who proposed to take over. We were chosen, as Kathy said she had a hunch and interested to see what we would do with it. But, to tell the truth, I had no idea what I was going to do with it. I just knew that you cannot complain unless you do something about it. I have to thank Kakiseni because some work that I’ve done seriously on stage has been picked up and extensively promoted on Kakiseni, and then picked up by directors who tried me in film and television works. So, it’s a platform that contributed to who I am today. Because of that I feel like I have a sense of duty to continue.

When we took over in 2009, the question that we were asking was, what Kakiseni is offering – a communication platform; is it still relevant? We went around asking all the important stakeholders, such as Ramli Ibrahim, Marion D’cruz and Jo Kukathas, and asked if it was still what they wanted. We asked them how had the industry been for them, what did they want from us, and what could we do for them? We had this conversation for about four months which culminated in Women: 100, where we had 100 hours of our performing arts dedicated to talk about women issues at that point. That’s really how we started – starting platforms to try out different collaborations. A lot of things start to fall into place, which means we didn’t plan them from the very beginning. It just happened as we went along, and I really enjoyed that process. - The new Kakiseni seems to be getting lots of cooperation from the government.

- I had the opportunity to voice the concerns of the [arts] industry to various different roundtables, such as the creative industry roundtable, the prime minister’s roundtable and the youth round table. I talked about how important the arts were as something that defines the creativity as well as the identity of the country.

We need to continuously push for it to happen and that’s when all the roundtables asked me what the road map was, what we saw ourselves doing. So again, I went back to the industry and asked them what they want, and we drew an extensive ten-year road map and we re-submitted all the road maps. And, it is through these initiatives that we then started our working relationship with the National Department for Culture and Arts (Jabatan Kebudayaan dan Kesenian Negara: JKNN), the Performance Management & Delivery Unit (PEMANDU) which is a unit under the Prime Minister’s Department, and the various different kinds of ministries.

When I believe in something I just keep going at it, keep knocking on doors. Before this, I never even knew the word lobby. Because of this experience I realize actually in other countries there are very specific roles and job scopes for people who lobby for certain things to happen. Is our country mature enough to have lobbies? Maybe not, maybe yes. We don’t know. But we won’t know the answer unless we try it. So, instead of complaining, we just see what we can do. It’s as simple as that. - Before becoming the head of Kakiseni, you were an actor, director, film director and TV producer, and then selected to be a marketing director at an international company. I believe you were still working in these fields when you started at Kakiseni?

- It was almost the same time. The switch from the arts to the corporate world doesn’t mean I’ve ever left the arts. I’ve always kept one eye on the [arts] industry. I was just doing what I can to contribute like the way alumni would at that point. I just wanted to add value whenever I could. It’s purely coming from that point, and then it evolved into what we’re doing today. Becoming the catalyst and the enabler to make certain things happen and move forward. Once I got into it, I realized a lot more things needed to be addressed.

Well, we actually still don’t have all the answers. I only know that there is a decline in the industry and we’re just trying to find out why and what we can do about it. Is there any factor that we need to take note of that is causing the decline in terms of audience as well as in terms of content being produced? Do we have the next generation of people wanting to work for performing arts? If there’s a shortage then we have to ask is there something we could do to remove or to do something about. Those are questions that need to be answered and need to be worked at. Those are important. These are not questions any artist on their own can do much about, since concentrating on anything else besides creation is compromising on their time and talent. Instead, if a dedicated group of people with the right interest look at it, it gets a chance for recovery. - When Kakiseni was re-launched in 2011, apart from Women:100 there was the re-starting of the Boh Cameronian Arts Awards (hereafter “the Awards,” which was one of the most impactful programs in the former Kakiseni since it was started in 2002. Can you introduce this Awards program and tell us the reason you decided to continue it?

- The Awards is important for two things. One, it is very important to recognize artists’ work. Not only does it work at the international level but also for the artists’ own self-esteem. The best people in the industry are judging the Awards. That’s more valuable than a lot of other things. It means the elders are approving what you do and they are giving you a ‘well done,’ and recognizing your work. That is very important as otherwise you cannot grow. This year is the 11th year of the Awards, but because of that, we will not close it. Even though we have to allocate money to do it, especially when our industry is still very young.

The second most important thing is that it also functions as a great showcase to show the other corporations how much mileage a company can get if they are involved with the arts. We need examples. If we don’t have a clear example, then no corporations will support arts. We are gaining attention from corporations slowly but surely. Now we even have calls from corporations asking what they can do with the arts. Of course, it’s still a long journey, but at least we have something to show. That’s very important for us. - Who are the judges for the Awards, and what kinds of awards are given?

- We have had many over the years, with some of the theater greats kick-starting the standard that we should aspire to, such as Marion D’cruz, Professor Dr. Mohd Anis Bin Md Nor and even Normah Nordin, an artist extraordinaire who has contributed to the arts scene for over 35 years. Today we still have Dr. Joseph Gonzales, Patrick Jonathan, Leng Poh Gee, Ivy Josiah, Reza Zainal Abidin and Wong Oi Min. Some judges were emerging artists when the awards first started but today, they are recognized for their contributions and are now serving as judges for the Awards. An example in case is Zalfian Fuzi, whose works were recognized with a few awards back in the year 2008, Ashraf Zain whose writing won his group the Best Group Performance (Theatre) in 2011 and Chang Fang Chyi who won the Best Solo Performance (Music) in the year 2013. The other notable judges include Fiona Gomez, a young choreographer, and Bilqis Hijjas, who runs dance programs for the residency and arts centre Rimbun Dahan and the MyDance Alliance.

There are four categories. Dance, Music, Musical Theatre and Theatre. Under each of them are another 11 categories from best director, to best play, best writing, best lighting, best sound, best stage design, and best ensemble performance and so on, depending on the needs of each category. Each of them will be judged by five judges, who will be watching the entire category the whole year. They will come together to ballot to ascertain who the winner is. There’s a mathematical formula and function to it. If you miss a show, then your weight as a judge drops. As judges have to watch the show throughout the year, the panel is naturally made up of established artists who live within Malaysia. The judging process is then audited by PwC for further credibility as part of their CSR program. - Awardees seem to be gaining lots of mileage out of this, including some going overseas.

- Out of more than 10 years of the Awards, the industry has seen successful artists going on to do more successful things after they were awarded. Did the awards give them that platform to do it? I am quite certain it helped. First of all, because it gave them recognition for their good work, and second, because they are immediately able to value themselves and have confidence to go outside of the country and compete internationally.

We have Mac Chan, a lighting designer, who is one of the leading award winners of all time in the Awards – he has won five awards, consecutively for lighting design. Today he is much sought after and his work as the Technical Director at Stage Centre Line Associates is well respected, and he has worked on the Singapore National Day Parade Show from 2009 to 2012 as the lighting designer as well as lighting up the Singapore Pavilion for the YeoSu World Expo 2012. We have composers and music directors like Llewellyn Marsh who went on to be picked by Universal Studios in Singapore to do work on the world stage. Then there’s the multiple award winning Lee Swee Keong and Loh Kok Man, both artists whose works have travelled extensively. And then there’s Lim Yeow Haw, a really precise stage director who is now based in Taiwan. I am sure that to a great extent, having their works recognized as an award-winning piece from Malaysia, gave them added value on the international stage. - How about the second aim to showcase arts to corporations and sponsors? Has that been successful?

- I would say not yet. The biggest difficulty—which is not just for us here in Malaysia but the same all over the world—is that people seem to see arts and business mission as two completely separate elements. How can arts play a role in any business mission is not immediately obvious to business at all. Even to begin this conversation seems almost impossible. But, we try one step at a time. Maybe we need some incentives. Maybe we give them examples. I have brought up how other cities are working to build a creative city, and things they can do to create quick wins immediately. But it’s a journey.

- What is the future vision for now for the Awards?

- There are a few things we want to do with it. The Awards only happens once a year and almost all the artists in the industry come together to celebrate. I want to use this positive energy to create more opportunities for us to recruit audience, to be seen in the public eye and to create more news, and also become more attractive to sponsors. This year we’re putting it on television, and we are opening up the Awards night to the public. We are also opening up the Awards to schools. We are going to have a category called the school section where schools are now encouraged to take part so then the school children can now have a better understanding of the industry from a very young age. It will be judged by professionals, to make it a good encouragement for them to start to aspire to want to be at a certain level. I think only when you have a dream can you improve yourself.

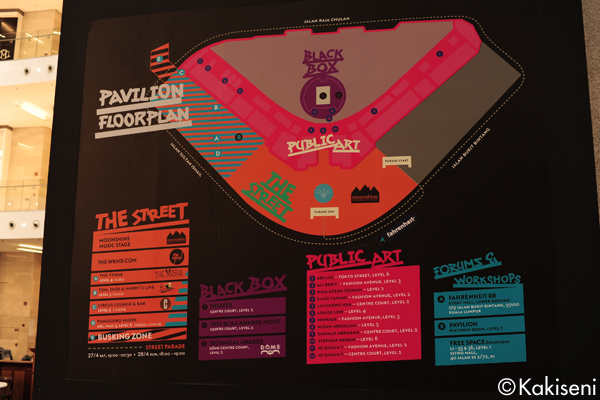

- Moving on to the KakiSENI Festival, last year in April 2013, the festival started for the first time to showcase both Malaysian and International arts in Kuala Lumpur for 10 days. It was very unique that the entire festival was held in the busiest and most vibrant shopping mall right in the middle of the capital city. Why and how did you start this festival?

- The main intention was to introduce the arts to the audience. We were having conversations with artists about the fact that people really don’t know that art is happening in the country and there’s a huge decline in the number of audience. There are a lot of really good companies already working the hardest they can, but if you go into the hall you still see that it is not filled to the brim. So, something is wrong. Just like the rest of the world, we are fighting with technology, we’re fighting with other interesting things. How do we overcome that?

So, we set up a black box in the middle of the busiest mall in the country and served arts like buffet, every half an hour there is a different show. High impact shows to introduce arts to people, regardless of whom they are and then let them think, “Oh, there’s still one more thing that we haven’t done. We have to go and watch a show.” In the first year we attracted 9,000 people all together, including a good 30% from the industry itself because they’re excited to see other country’s work. You could repeatedly watch so many shows because it was a full day of shows and was free. But actually, what we wanted to do was to catch audience who are walking by at the mall.

But of course, at the same time, they are people who are not used to it. If people are not used to it they don’t know what we’re doing. So, even after asking us, they still don’t know what we’re doing. But, it’s going to be a process of introducing. The idea of watching a dance piece for 45 minutes is common for arts people, but to someone who has never seen a dance piece longer than 4 minutes, to imagine watching a dance piece for half an hour, let alone ask them to pay for it, is not an easy task.

To break down this barrier, maybe we need to speak their language. “Wow, very good show, free to go and see.” Being free is not so good in the long term but at this point we wanted to really attract people to let them try it. As a result 80% of the audience from our survey answered that they will want to know what else is happening across town.

So, for this second year of the KakiSENI Festival in September 2014, we are planning to have a system of getting them to act immediately on the fact that they want to know more, by buying tickets on the spot for other shows happening during the same time. We want to be able to induce them to act on their immediate impulse. Maybe we can also consider discounts or corporate tie-ups as well. - KakiSENI festival 2013 had several curators for Black Box, Music Stage, Talk, Busking, Fine Arts and so on. Who are the curators?

- For the Black Box there were two curators: Moo Siew Keh, a writer and arts critic who had mainly selected local Malaysian works, and Ben Cutler, UK based actor and project manager whom we have worked with in international arts exchange before. I trusted what they have to say, and a lot of the shows were impactful, not just for the audience but also for the artists themselves. The music program was curated by Reza Salleh and Fikri Fadzil, public art was curated by Sharmin, who runs the art gallery interpr8, and the forum curator was Grey Yeoh, who has coordinated several talks regarding how to keep the arts sustainable.

For fine arts, we focused on site-specific installations that can induce some thinking, as well as featuring new artists’ work. For the music program we focused on more established musicians who’ve been on the scene and who could pull a large crowd, but not necessarily commercial ones. Then we put them in very strange sites you didn’t think there should be art or performance. The whole thing was to shock the system. The idea was that a person who has never seen arts before will, when they leave that space, want to see more arts. That’s all. It’s very simple. - It seems like you are applying authentic marketing strategy you acquired in the corporate world to the arts. What made you decide to work on the arts, not for the more commercial areas of TV and films?

- I am still involved in film and television, but I keep it quite clear that I only use my work from film and TV to influence my arts and bring it out. I feel that the way art is different from mainstream [entertainment] is that when it’s eventually documented, the art works become the reference points. Twenty or 30 years later, when we need to make a reference to a country’s identity or culture, they will look at the arts. Entertainment will never be taken as seriously as art works, because it is manufactured. Documenting what is happening in the arts in the next 30 years in Malaysia will be very important for our own future. That is why I’m trying to make sure that it is kept alive.

I generally like people. I generally like people’s thinking, and to see why they are influenced in certain ways. I believe there is always an expression, bad or good. It’s also whether the person enjoyed the process or not, and this enjoyment varies from one person to another. In the future, when you look back, these expressions will really make the identity of that era. That is what that is really exciting for me to imagine. - In 2013, apart from KakiSENI Festival, the Kakiseni Arts Exchange (AEX) was another major program. It is a program started after the re-launch of Kakiseni and was in its second year. What is this program about?

- The idea behind this was simply collaboration. If I cannot get artists out of the country, because they will have all kinds of reasons, then I thought I would bring some artists from outside in, to induce conversations, and to get people excited again.

Another purpose was to look at where we are as a country, what kind of things we are capable of, how far we can stretch. So on one hand it’s a small experiment to gauge what else needs to be done. On the other hand, it is to excite the industry as a whole. - In 2013, the second year of the AEX, the two directors were European based Carlos García Estéves and Iran based Hamed Zahmatkesh, as well as including some experienced artists from Malaysia, as mentors. And, you also gathered young international artists who applied by themselves to join the project. How did you plan the project?

- Every year we have a different thematic. For year one in 2012, we wanted to introduce to the world the different kind of skill sets that Malaysia artists will have. The theme was Collaborative Outreach. We pooled together 28 artists from 11 countries with very different skills and backgrounds, such as Andre Jewson (Australia), Sam Scott (New Zealand), Alfian Sa’at (Singapore), Sergio Martinez (Spain), and the artists from Malaysia were Ling Tang, Ayam Fared (Farid Jamaluddin), Boyz Chew Soon Heng, Jerome Kugan, Mislina Mustaffa and so on.

And for the second year in 2013, there were two projects. The first one was to give Malaysian talent a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to work together with award-winning puppeteer and thespian Hamed Zahmatkesh in Tehran. After more than a month of learning and sharing, the Malaysian participants brought a localized interpretation of the show back to Malaysia for a three-week outreach in several cities and villages, giving children in rural communities in particular a unique taste of the performing arts, right in their own backyard.

The second project was the continued project of collaborative production. For this, we wanted to match class A to class A. So we invited a class A director from overseas and matched that person with a Malaysian class A director, Jo Kukathas. The directors picked the participating artists, who gathered under open call and were very talented in different skills, including Mak Yong, Gamelan, traditional puppet, music and acrobats. It was really fruitful and stressful for everyone to understand what he is trying to see and to put something together within three weeks. - How did you choose the directors?

- We got references from many of our partners. Philippe Gaulier, who we invited as part of AEX 2012 is one of them. Through cross references with many people, we came to this year’s director. From our office Ling Tang also worked as curator director for AEX.

Kakiseni do not own a big board of directors. It cuts down on the structure so everybody is empowered to do the best that they think they can. The structure of the organization is very simple so we can work faster and go further.

I think my talent is putting the right people together most of the time. I always have the same modus operandi. I set the brief at the very beginning. Then, after whatever takes place, it is organic. After that, I hope these right people are indeed right, and I will only concentrate on getting the money to do it.

The only thing I would be very particular about would be how the poster looks, what the poster is saying, and what are we selling. Because ultimately, I’ll look at messages seriously and think why would you say this? Who would understand what you are saying? What are we selling? Those things I am very particular about, but I will leave the [artistic] content to the team. - Do you feel that your international exchange program is succeeding? Is it getting people excited as intended?

- Yes, we have got the feedback saying artists are craving for more. It was great in the first two years, and now I need to put in place a really stringent indicator.

- I would like to ask about Kakiseni Grants program (hereafter “the Grants”), started in 2011. I believe this is one of the first governmental funding programs to support arts in a transparent and scheduled way in Malaysia, isn’t it?

- I think the Grants program is one of the most meticulous things Kakiseni has attempted in the last 12 years. It started in 2012, but it’s meticulous simply because of the amount of work that’s involved that we didn’t quite foresee. We wanted to become the enabler for things to happen, so in order to speed things up we really worked as quickly as we could and then tried to hurry as many people into the system as we could. So, [we did everything] from setting up the panel, to setting up the terms and conditions, to deciding how certain things should be done.

We have five [grant] categories. One is grants to Reduce Production Costs, another is the Mentor-mentee Programme, in which experienced mentors will support the young artists’ productions, then there are the outreach grants (name changed to Arts in the Community grants from the second year), and the Apprentice Programme grants to support young people who wish to work in the industry, and finally the New Malaysian Works grants. The numbers of approved programs are about 20 for the outreach grants and more than 40 for the Reduce Production Costs grants. We are the ones who do the calling for applications, checking the applications submitted, gathering the panellists, announcing the results, arranging the contract details, holding the press conferences and working with the National Department of Culture and Arts every step of the way. - How much is the total budget?

- It’s approximately 4.4 million ringgit (approx. 1.3 million dollars) [this year]. The money goes directly from the government to the people. Not to us. It’s very important that there is no paper loss. We don’t want to have any flaws in the transparency. We are just doing all the work to make it happen.

- What kind of impact did the Grant program bring to the industry?

- We started calling for applications in 2012, and had done all the necessary work by December 2013, except for the New Malaysia Works grants. It definitely brought us more productions last year for sure, but we are now discussing the role and scheme of the Grants. The program for grants needs to change.

- Kakiseni used to be working more as the online platform and database of the people. The current function for the database seems to be more focused as a platform for young talent to promote their activities.

- Yes, it’s more for that now because the established artists have already found their own platform to do it themselves. The Internet is so much more accessible today. Before, in the decade of 2000, to do a website meant a ridiculous amount of work. But today, anybody can do a website so easily, and with very simple steps you can have a page with your own name, which is really a good thing what the technology has been doing.

The role has changed somewhat for the website, kakiseni.com. Now it is more about listing of what is happening in town, and our independent ticketing function. We have built a ticketing function that can be used by even the smallest company when they have a show in an alternative venue. We also have a blog exchange where critic reviews are being put up about shows, which we found is insufficient in the current market.

Other than that, today people already have spaces to share and get connected. They can do it on their own Facebook page and tag the whole world, so they don’t need to go and find specific websites to do that, which is a really fair movement that affects all kinds of industries. - So Kakiseni moved on from an online platform to a real-world platform using many different strategies, such as festivals and exchanges.

- Absolutely. It became more physical, more real. The online listing and other functions are still there. And, we are still thinking how we can play a stronger role in the digital age, but everything needs money from here.

- If you had big money, what would you want to do?

- Oh, my god. I’ll have a mobile application that makes it really easy for you to experience arts from point A to point Z. You know you have to get a taxi to most of the theaters in Kuala Lumpur. So using this application, you could get a taxi easily, which could already be paid from the very beginning. It goes straight to the theater, you watch the performance, you come out, you can say whatever you want about that show on the app, and you can buy your next ticket off the application. At the same time, you can even find friends to go with you on your Facebook page. So at the next show you all meet up near the theatre, you can search and book a reservation at a place for dinner before or after the show. Then your taxi will be waiting for you wherever you are so that you can safely go home. You can arrange your whole journey. Wouldn’t that be awesome?

So, it’s the point A to Z of the entire experience. When you think about what is stopping us from going to a theater show, it’s because you have no friend to go together with, no transportation and you don’t know where to eat. I’ve got work so it’s difficult to book a ticket, I don’t know what’s happening. With this app I could cut all these excuses away, it would give you no excuse and make sure it’s a wonderful time. How’s that? That’s what I want to do. - Let me ask a few questions about yourself. You started your career as an actor. What brought you on stage?

- I was always a performer even back in school. I’m always the girl who wants to be on the stage, so when there’s an audition, I will go. I’ve been quite lucky in most auditions; I usually have a pretty good success rate, even if it means being one of the people working backstage. I was always happy with that because I understand the road to stand as an actress is a long one.

- Why did you choose to be on the supporting side of the arts?

- I think what I’m really intrigued with is these conversations that you have in the performing arts arena. With television, for example, the conversation is never as deep or never as thought-provoking. But, in performing arts it’s really the deeper you are the better it is. It has always been this one area that left me the most insecure. I could do television, or I could do film—and I’ve been awarded for works in both—and I could market formats to different countries successfully with either the shows coming off with top ratings or acclaimed. But, when it’s working for the stage, I’m never happy, never satisfied, never sure, always insecure. It’s really strange to worry about what people say, what people think. I’ve directed quite a bit for the stage and it’s the most tormenting period of my life but also the most thought-provoking. It’s the most alive I’ve ever felt and all that impact is quite amazing. So it’s not just another thing I’ve done. It’s always the thing I have been doing that caused me the most pain. I think artists are all like that and maybe this is the closest presence that I am able to feel. We want to be in pain, we feed on the pain.

- I would like to ask your views on the performing arts in Malaysia. People say that the scene in Malaysia tends to be divided by the culture and the language. Do you think it is still so?

- While artists feed on insecurity in their work to continuously produce more, as I just mentioned, not many artists take to becoming uncomfortable dealing with things which are not art to them, such as the business side, the marketing, the publicity and the P&L. Yes, it is difficult. Because when you’re trying something different, something you never thought about before, it is crossing your comfort level. It is difficult to expand your work to an audience of a different culture that you don’t know, that you don’t understand, or you have never known before. Yet they are just complaining that people (audiences) don’t come. But, nothing has been done to tell these new audiences to come. I am also a stern believer that artists should never compromise their time and energy to turn arts into business. Because, it is not business. But content is content and we need other support to help with the sustainability and the outreach to different kinds of audience.

I feel [the divisions of ethnicity, language and culture] is going to get worse. People fear, and because of all this, things are becoming a lot more non-inclusive. That’s why in most of the platforms that we’ve provided one key criteria is that it must really be cross-cultural. It is never about their languages and their education background but it’s about creation. It is obviously not moving at the pace we imagined, but then again, in all kinds of change it takes some time before it happens. People are more comfortable in their own zone. If it’s already difficult for the successful artists, imagine how it’ll be for the upcoming and emerging artists.

Another reason behind the perception of divide that we have is that artists are not performing enough – not at a quantum where they have the opportunity to look at approaching audience from different backgrounds and compare the responses. Once, we had Krishen Jit, who would talk about this issue, and people respected his point of view because of his background, for his involvement and experience. But today, who else do we have? This needs to be an ongoing conversation, not one that is looked at as instigating divide but as a means to overcome it. - How about the inter-ethnic or multi-language collaboration works that have been done in Malaysia before?

- When the form has less language barrier then it’s easier to transcend the different culture. For example, people may be less afraid to go and see dance work because they don’t have to understand text. But then it’s the level of interest that we’ll need to plant here. And then it’s the marketing.

Multi-language works may be appealing, for example, like the way Jo Kukathas has always involved many elements of culture and backdrops in her pieces. But if people are not exposed to the information because it’s perhaps only marketed in English, then other segments may not realize what they’ve been missing. So, there is a need for different strategies and long-term attempts. - I see. What are your thoughts about Kakiseni’s role in this?

- We do whatever we can, but the artists themselves also need to shift and change. If some company comes to us to ask how to reach a certain target [audience], we can help. However, we are not going to ask around if they want to reach an audience from a different language group. Do you want some Chinese audience? Do you want some Malay audience? I’m not going to do that. I believe in capitalism, where supply and demand pull together. I believe in exchanges. I can only excite them to create more, to let them try something new. That’s all I can do. But beyond that everybody has to do something. If they ask for help, sure I will do whatever I can, but it has to happen naturally.

It seems there are fundamentally similar problems in Japan and many other countries. In dance, music, theater, fine arts, traditional arts, there are comfort zones in each one and each have different audiences, and it seems difficult to achieve crossover. Of course approaching to the overseas people with different cultural background is much higher challenge. At the bottom this is relevant to many countries and thus creative attempt to challenge this issue is very intriguing. - I agree, and we have to realize it ourselves. What do you feel is the other major agenda for the Malaysia’s arts scene?

- Definitely funding. Many cases artists don’t have someone looking at fundraising or marketing properly and they try to do it themselves, thinking that it can help save costs. But all these are very specific job scopes, and they shouldn’t beat themselves up and be personal about it when it didn’t work well by themselves. But, having said that, it’s also an artist’s journey. It will not change until they start to realize why it is not working or that they need to share these works with someone.

There will always be an issue like funding, and it is a worldwide issue. But more pressing, in my opinion, is that in today’s environment, what is endangering the works of artists is brain drain from over-expression. They’ve already expressed their thoughts in many different platforms via the social media constantly, so they’re suddenly struggling to find new voices for new works.

And then, we are also declining because we are in really good times. We have no war, we’re not dying from hunger or any catastrophe and we are complacent. The only voice [today] is the voice of complaining. That’s just one mode of expression, and we need more. - Lastly, please share with us your vision on collaborating with other countries?

- I think what’s interesting to note is that the artists who are invited from outside to Malaysia are invited by established artists themselves who are yearning for a bit more relationship outside and want some new challenges. If you are a new artist, maybe you look forward to working with some other artist outside because the world now is so limitless, or just so that you can say that you worked internationally.

I don’t think working with other countries is uncommon, nor can it be considered a trend. I just think that it is necessary. It’s just easier for people to come in to Malaysia to do things because English is used broadly compared to most other Asian countries.

However, to the audience, I think their concern ultimately is still whether the end result of collaboration is a good piece of work or not. They don’t care who the collaborator is and they don’t care if it’s somebody from Denmark, for example. Unless it’s really good they’re not going to care. I think the challenge here is really getting the audience to know that something is happening. At the end of the day, whichever country they came from, it’s really about whether the show is good.

Low Ngai Yuen

Malaysia’s Kakiseni,

A platform for the performing arts

Low Ngai Yuen

Director of Kakiseni

In the multi-ethnic country of Malaysia where Malay, Chinese and Indian represent the three major ethnic cultures, Kakiseni was founded in 2001 as the only online platform for artists to gather online, post information about productions and events, share news about auditions, reviews, interviews, and thus functioning as a hub for the artists and for the arts information. Since Ms. Low Ngai Yuen assumed the role of the organization’s second director in 2009, Kakiseni has been transforming into a platform with a fuller range of programs. Apart from keeping and expanding the legacy of the Boh Cameronian Arts Awards, the new Kakiseni has been presenting new programs to stimulate and inspire the Malaysian arts scene, such as KakiSENI Festival and the Kakiseni Arts Exchange program for international exchange. In 2011, it also started the Kakiseni Grants program together with the government to establish a comprehensive scheme of public funding for the performing arts in Malaysia.

With its rapidly growing economy, Malaysia now boasts a National Theatre (Istana Budaya) with South East Asia’s top quality of facilities, while its KL Performing Arts Centre, Malaysia’s first full-scale private arts center, helps the arts grow by nurturing young talents and producing internationally acclaimed artists. Theatres and galleries are also being built one after another inside the growing number of shopping malls.

With the aim of improving this environment and creating a vital ecosystem of the arts, Kakiseni continues to be a valuable organization that not only creates its own projects but also works to build a network and infrastructure to support and strengthen the performing arts environment.

Interviewer: Mio Yachita, The Japan Foundation Kuala Lumpur

Kakiseni

https://kakiseni.com/

(C) Kakiseni

Boh Cameronian Arts Awards

(C) Kakiseni

KakiSENI Festival 2013

(Apr. 22 – May. 1, 2013)

(C) Kakiseni

Theatre “Black Box” in shopping mall

Sun Son Theatre Into the Flood

Louise Low Seok Loo Not blue, but colourful (sculpture)

Rhythm in Bronze

Kolumpo

Kakiseni Arts Exchange (AEX)

Puppeteer and thespian Hamed Zahmatkesh’s project “The Abrisham Journey”

(C) Kakiseni

Related Tags