- We have heard that before you sought to become a director you had wanted to be a painter and had been painting from quite a young age. Would you tell us from what age and in what style you painted?

-

The earliest form of play that I remember from my childhood was drawing pictures. I remember copying all kinds of illustrations that were popular at the time. By the time I was going to nursery school I began learning to draw and paint from a teacher, and by the time I was in elementary school I was studying with a formal art school. There I learned to draw still life and from the beginning I was pretty good at it. Whenever there was a painting contest in elementary school I always got the Gold Prize and I remember thinking of myself as a good painter. Soon I wasn’t satisfied just to win prizes at school, so I went out and got information about painting contests run by the newspapers and national open exhibitions, and I submitted paintings to as many as I could.

- Were there any other forms of play you did as a child that could have contributed to your creative activities today?

Pranks. For example the name Penino in my company Niwa Gekidan Penino’s name was my nickname when I was in middle school, and it came from a prank I played one day on the way to school. One morning on the way to school it suddenly began raining cats and dogs. It was such a violent rain that I got the feeling, “Isn’t this like war?” It was at the time when the Rambo movies were popular. One thing led to another and before we knew it I got about ten of my friends to join me in taking off our clothes and charge through the rain naked, holding our umbrellas like guns all the way to school. We were completely naked (laughs). And since, naturally, our penises were hanging out as we ran, everyone started calling me Penino from that day on. I would think up pranks like that and get everyone involved in doing them. I still consider this prank aspect an important part of my creative process today. But in middle school I guess I went too far with the pranks, because my family would have no more to do with me. After I graduated from middle school they sent me away from my home in Toyama prefecture to go to a boys’ boarding school in Chiba prefecture where all the students lived on campus in dormitories.- You have frequently said that the boarding school you went to in high school was famous as a school for undesirable types. In that kind of environment were you continue to paint and play pranks?

As for the prank side, there were a lot of students there that had been involved in pranks that were much worse and on a more serious scale that, with my contrary nature, seeing them made me decide to get serious about my studies instead. I got the feeling that if I got involved with those kids I could get in some serious trouble. I didn’t want that to happen, so I buried myself in my studies. As for painting, I was fortunate that there was a math teacher at the school who was very knowledgeable about art. What’s more, he lived in the dormitory too. So, almost every night I would visit his room to watch movies or have him teach me about painting or talk about art. What I got into at that time were the Surrealist artists. I was aware from a young age that I had an interest in that kind of other-dimension, somewhat repulsive kind of world, but when I first saw the paintings of Salvador Dali and Marcel Duchamp I realized that I loved the kind of art they called surrealism. And, I still like their works today.- Now that you mention it, there definitely does seem to me to be a kind of other-dimension quality to the time that flows through the works of Niwa Gekidan Penino similar to the world of the Surrealists. For example, in the work Kuroi OL (Dark Office Ladies) (2004) where you set up a long tent in the public square in front of the West Exit of Shinjuku Station in Tokyo with a channel of mud running through it, there is an office lady in black mourning clothes who is constantly hanging out stockings to dry. In the busy everyday reality of businessmen rushing to and from work in the big Shinjuku district, the scenes of office ladies’ everyday life created a different flow of time that was daydream-like.

That was a work done just after I graduated from university. If theater is an art of time, then that was the first work where I was aware of a sense of time that I felt good in. Looking back through my memories, I believe that I was aware of and liked such unique warps of time even before I encountered Surrealism. Part of the reason may be that my family home in Toyama is a traditional Japanese style house built about 120 years ago and it has a Noh stage and a tea ceremony room, a garden and on the other side of the garden is another small tea ceremony cottage, and there is even a room for doing calligraphy.- That’s very impressive.

Not really. The area of the grounds devoted to those rooms is large but our living quarters are actually quite small. But, the grounds of the home have a special atmosphere where you could here the clonk of the bamboo shishiodoshi clapper. The strange sense of time that flows through that house is something that I have always loved, and I think it was there that I realized how interesting it could be to manipulate the flow of time.- So, during your high school years you discovered Surrealism and you were following your dream of becoming a painter. What made you suddenly decide to go to medical school and become a psychiatrist? Could you please tell us how that came about?

At the time I began to think about my future and the career I should purse, Japan had fallen into a serious economic recession and it was no longer a society where you could make a living just by doing what you wanted. Even the painting teacher I mentioned earlier that I respected so much told me, “If you want to continue doing the things you like, get some kind of professional license first, just in case.” And that made me think that, indeed, must be the way things are. So, I decided to get a doctor’s license. The reason I chose to go to medical school was simply because my father is a doctor. Also, I had done enough extra studying in high school that without knowing it I had accumulated enough knowledge and credits to get into a medical school. I also thought that the medical profession is one where you can make enough money, and it would satisfy my parents, so I changed course in my third year of high school. However, because it was a career course that I had chosen purely for practical reasons, once I started medical school the studies naturally became a pain. I had no motivation at all to study medicine. That fact that I chose a profession that I was so fundamentally against my nature is proof of what a fool I am.- Then, as you were studying hard to get your doctor’s license, you began doing theater. Could you tell us in a few words what led you to become involved in theater?

The university I went to had a unique program in which the students spent their first year living in dormitories on a campus at the foot of Mt. Fuji. During that year there was no clear distinction between classes and club activities and we were all given the opportunity to do things like horseback riding, Japanese Kendo fencing and Karate together. In other words, it was a system where we were free to enjoy doing what we wanted. One of the activities scheduled for us to enjoy ourselves was a Christmas pageant at the end of the year and we prepared a play to perform in it. That time I wasn’t participating as a playwright but as an actor. That was the first theater experience of my life. The title was “The Troubled Director” and it was simply a story about the continuous worries and uncertainty of a director. At the time, none of us knew the word for a theater director ( enshutsuka ) so we used the word for a movie director ( kantoku ). (Laughs) It was a very serious drama and, for some reason, when the final curtain came down, everyone in the cast started crying. That made us want to continue doing drama, and since there wasn’t a drama club in our university, we started one. But, I wasn’t interested in doing serious drama. After much searching in high school, I had arrived at a kind of obsessive painting style where I took with a large canvas and started filling it up with minute, highly detailed images. Doing that, I had reached a point where I couldn’t paint anymore. So, I wanted to do something lighter, something you could laugh at. I wanted to do comedy of the type I had seen performed by the Meiji University’s Sodosha theater company. So, in my third year at university I got together with members of our drama club and we started Niwa Gekidan Penino.- Would you tell us how many people there are in Niwa Gekidan Penino now?

Including me there are four. First of all, I make the final decisions as the writer and director. Then there is a person I confer with on this and that before coming to the final decisions. There is another person who acts like a curator giving me academic advice about things like what kinds of productions there have been and how they have been directed, and what is happening now on the international scene. The fourth person is a technician who puts my artistic ideas into blueprint form.- You were born in 1976 and you started Penino in 2000. In Japan’s small theater world at the time, cynical comedy of the kind seen in Suzuki Matsuo’s Otona Keikaku and Kerarino Sandorovich’s Nylon 100°C was popular. But, your plays are different from that mainstream comedy. Rather than that type of cynicism or cutting humor, your scripts seem to have a free-wheeling riotous flavor that reaches toward the surreal. Were there any directors of the previous generation that influenced you?

I have never seen any of the plays of Matsuo-san, and I just saw one of Kera-san’s plays for the first time last year. What I liked best by far in my university days was the plays of Juro Kara. I first saw a performance of Jaga no Me on a television program when I was about 20 and it really stunned me. It was like painting and film and music all rolled into one, and I felt it was the most interesting thing I had seen in my life. There are a number of reasons why it was so exciting, but what I would give as the first is the uplifting feeling of the theatrical space it created. I didn’t understand the story at all. I didn’t even understand the lines that were being spoken. But, for some reason the space was full of exhilarating excitement and expectation. I loved that feeling tremendously. And, I like how Kara “draws pictures” in his direction, actually I fell in love with its beauty. The lighting would come on and the actors would rush in and line up and it all formed a perfect picture. Then the lights go out and when the next scene starts they rush in again and create a different picture. Having been a painter myself, it was extremely interesting. I never joined Kara’s company but I think it is safe to say that a lot of my know-how for creating stages is things I learned from Juro Kara. Seeing Kara-san’s stages made me realize that it was possible for a play to be based on the simple pursuit of pictorial beauty. Until then I have been troubled quite a bit by the inability to write scripts, but Kara san’s work made me think that perhaps a script wasn’t really necessary to create a play.- We hear that now you don’t write scripts at all. Instead you draw storyboards to create your plays.

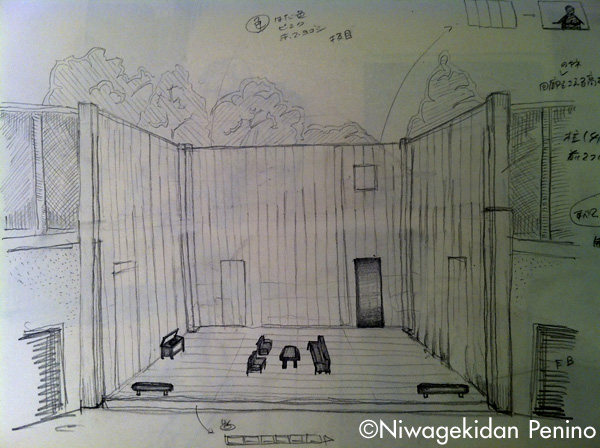

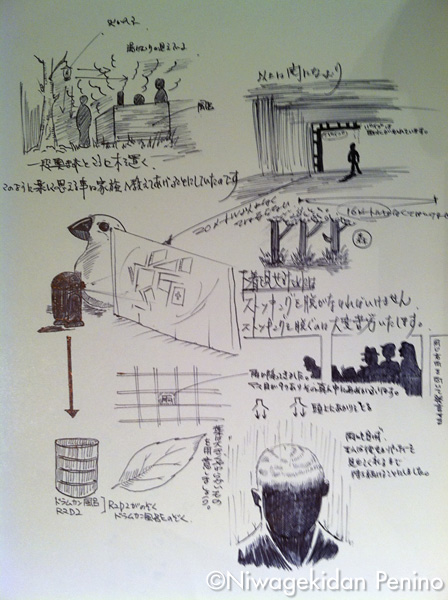

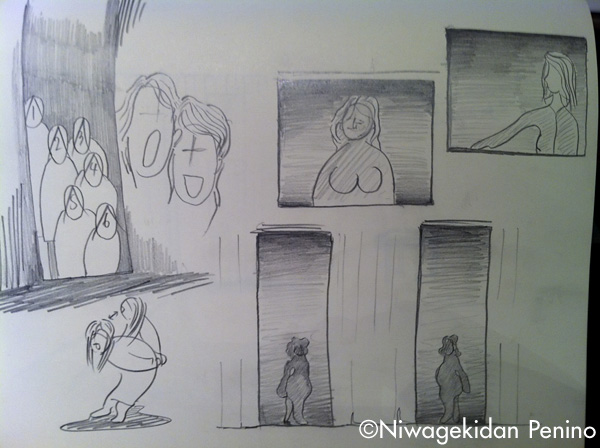

That’s right. There was a period three or four years ago when I tried writing scripts but it didn’t go very well. I’m not suited for it, the act of writing with words. There are too many elements that get lost by putting things into words. So, lately I have returned to the method of drawing storyboards and directing from them. Of necessity, the quality of the work increases with the number of storyboards. It begins with the completion of a first picture, and that leads to the idea for the next picture. That process continues one storyboard after another like a row of dominoes knocking down one after the other. And, when that leads to a good final picture, a satisfying work reaches completion. That is what the process feels like.- We certainly do get the feeling that each scene in your plays is framed with the artistic precision of a painting. For example, in last year’s Chekhov? (2010) based on a thesis about Chekhov, the impression was one of a beautiful painting composed of the perfectly controlled figures and motions of the people on stage, without regard for the human confrontations and internal conflicts.

When I’m working as a psychiatrist and seeing thousands of patients, I can’t enjoy works like those of Lars von Trier where you have characters that clearly have personality disorders. You would understand this if you led a life like mine where I am working day after day from 8:00 in the morning listening to people tell me things like, “I was raped by a person I had trusted.” It naturally makes you want to think that there should be more enjoyable things in life (laughs). That is why it is hard for me to be interested in Chekhov’s plays. From the standpoint of a doctor, you take it as a given premise that the world is a messed-up place. But, people have to accept all that and carry on with their lives. We have to try to live our lives comfortably. That leads to the feeling that it might be OK to enjoy yourself by thinking about erotic things or things that make you laugh. That is why I don’t bring any serious psychological portrayals into my own words. I would rather not bring those types of elements into my works.- In your company’s early productions you did a variety of experimental theater works that stepped outside the conventional framework of theater. For example, in your work Dark Master (2003) you had the spoken lines transmitted to headsets worn by all the members of the audience, and in Mrs.p.p.Overeem (2003) you had the audience seats sectioned off into cubicles with boards and delivered the line to each cubicle on electronic displays. What were the purposes of these kinds of experiments?

One aspect of my creative process for plays is that I am always thinking about how comfortable the audience will feel and they feel watching the play. In short, I pay a great deal of attention to what kind of theater experience it will be for the receiving side, the audience, rather than obsessing about the precision of the play itself. This approach perhaps has the influence of Nintendo in it. Video games were really popular when I was a student, and makers like Sega and Sony were also bringing out lots of new game consoles. But the makers besides Nintendo were mainly concerned about improving the definition of their picture to make the images look as real as possible. But, rather than trying to increase the fidelity of the images like that, Nintendo focused on what would be most fun for the gamer. They were interested in the “playing experience” they offered the players. I still appreciate that stance very much today. So, in my plays, you could say that I am not concerned as much with increasing the fidelity of the play but, rather, with how to make the audience’s theater experience itself more interesting.- In 2004 you remodeled your apartment in the Aoyama district of Tokyo to make it the small theater “Hakobune” (Ark) with a 25-person seating capacity. Was this a result of your desire to try to make the audience’s theater experience more interesting?

Well, you could see it that way, but there was also another reason. By creating my own studio in that way, I wanted to make a concerted effort to thoroughly explore my policies as a director. Doesn’t it seem that the profession of theater director is a rather vaguely defined thing? You could say that the skills required for the profession are rather unclear. So, here in Japan when a person called a director is given the job of staging a new work, they go about it in a sort of trail and error fashion. In my case, I felt that if I were going to continue to work as a director, it wouldn’t be good for me to approach the profession with such a vague attitude. I thought it would be best for me to at least try to grasp what lay at the core of approach as a director. As I was thinking about this question, I recalled how Marcel Duchamp made miniature models of all his works in boxes that he could carry around with him. That story made a lot of sense to me and made me think that I should create something where I could grasp all aspects of my work in one view. That led to the idea to create my Hakobune theater in my apartment.- The maiden performance at your Hakobune theater was the 2004 performance of Chiisana (small) Limbo Restaurant . For that play you created an unimaginably strange space with syrup dripping from the ceiling and the floor covered with an expanse of vegetable fields, all in the small single room of the apartment. Did actually staging a play there lead to any insights about your policies as a director as you hoped?

It made painfully aware of the fact that I am only interested in pictorial elements like the position of hands, the angle of the body and the color of the space. It was also interesting the way it made clear what kind of color quality I like. I tend to like to use colors that look like they are covered with a layer of dust. It is not that I choose that kind of color to achieve a sense of old nostalgic things. It is simply a matter of lighting effects. The stage art in Cantor’s plays is, I believe, always done in colors that look like they are covered in dust, and when I actually used that kind of color in my stage art I found that it is in fact a highly calculated coloring. When an entire set is unified in that kind of color the lighting can be used to create a great variety of different qualities. Simply changing the lighting makes it possible to produce completely different qualities of expression for the different scenes. Staging plays in my Hakobune theater really helped clarify my approach and sensitivities in the area of color and lighting.- So, as a former painter you approach stage creation with the same process and sensitivities as when creating a painting. That suggests that you would also be interested in what for the play could be likened to the painting’s frame, namely the theater proscenium.

To be sure, most of the theaters in Japan are not very attractive places. I would like to see a bit more sense of quality, or some distinctive quality that would make them stand out. I can’t understand why they design them with the same kind of anonymous look as any station building. That is something I really dislike, but I have my Hakobune and I think it will continue to be the base of my creative activities. When I am invited to do a production somewhere else, it always comes down eventually to a question of budget and I can’t ask for too much extravagance (laughs). But if someone were to suddenly give me a big lump sum and say I could build my own special theater, I think I would make a theater with seating for about 300 and a building that looked like a fine old temple.- You really do have an affinity for unusual spaces. Many of the playwrights of your generation write plays that are based on an extension of reality found in the material from everyday life. Is it safe to say that you are not interested in that kind of theater?

There was a period where I tried imitating that kind of “theater of the everyday.” Around 2007 I was asked by a producer if I wanted to try directing a production of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck . For that, I had to direct for the first time in my career a play that had a stage script, spoken lines and conversation. To prepare myself for that I wrote a script in a “theater of the everyday” style for a Penino production titled Egao no Toride (Fortress of Smiles). But, how should I say it? For everyday type acting there is nothing that I can really direct the actors to do, other than what comes to them naturally, is there? All they have to do is watch the variety programs on television for a week and come up with some ideas. It really made me mad. For me, going out of your way to bring reality into the theater was actually defying the essence of theater, and I couldn’t understand why we should make effort to bring the everyday into theater, which is inherently a realm of images. Later, something that I felt while I was staging The Wild Duck was how unnatural it felt to direct a play in manner where you are saying, “OK, now we will rehearse pages 1 to 5. As a director who wants to bring to create stages with a quality of time that is not found in everyday life, chopping up that time into arbitrary fragments like that makes it very difficult to grasp the sense of time that I, as the director, want to keep flowing through the play. In our company’s rehearsals we always go through the whole play in each rehearsal. For these various reasons, I realized how poorly suited I was for directing plays in the traditional format.

- Could I ask you to tell us your thoughts about acting? You are not interested in psychological characterization. You don’t like actors using superficial techniques. That implies that you have no interest in actors who are skilled at acting roles of modern theater standards like the works of Chekhov and Ibsen? Would you tell us what your definition of a good actor is?

First of all, I am looking at the overall picture as a composition, so I am concerned more about the overall balance more than the individual actor qualities. The appearance of the actors as objects placed on the stage is important to me. About my personal preference … How shall I express it? I feel drawn to people with faces that look like they have been persecuted or discriminated against all their lives (laughs). As I said to the three men who acted in the production Extase that we staged in Shizuoka Performing Arts Center recently, actors are people who do worthless things on stage and then have to act proud of themselves and claim their worth as “attractions.” I believe that kind of misdirected strength of will, or nerve, is similar, for example, to the energy emitted by a person has been persecuted or the subject of discrimination. I feel that kind of person emits an aura of unshakeable self-confidence of a form similar perhaps to an outpouring of resentment.- That is an interesting idea. In any case, what you want is for the actor to stand on stage with a confident, unshakeable presence?

That’s right. In proper terms it is “Being confident in one’s cowardice.” That is why I tell the actors that appear in my plays to choose one of three attitudes to stand on the stage with. The first is to take to the stage as if you have played this role in 50,000 performances already and this is your 50,001st. The second is to act like an actor who receives a million dollars per stage. The thirds is to act like a person who has been thoroughly discriminated against by society but you have the job of going on stage and entertaining people. I believe that if an actor goes on stage with one of these three attitudes they will be attractive as an actor. In short, the important thing is how the actor draws a line that separates them from the audience. The more clearly that attitude of distinction is defined, the better the actor will be. I think the same is true of the play itself as well. It is always a matter of attitude.- That is fascinating. You profess to have no interest in the inner psychological machinations of people and yet you worked as a psychiatrist (laughs).

That’s true. I think I was no good as a doctor (laughs). I don’t see patients anymore but when I look back a few years, I think I basically didn’t know what was sick about the patients I saw. For example, there was one patient who complained that he only wanted to take pictures of dead cats. But I didn’t see anything wrong with that and suggested that he go ahead and take lots of pictures of those dead bodies. Now he is a successful photographer. The idea for Frustrating Picture Book for Adults also came from a former patient. It was a person who had a guilt complex about masturbating. That led to the creating of that kind of play where everything that happens seems to have sexual undertones. It may be improper to say this, but rather than getting serious about patients’ problems, I become fascinated by them.- Frustrating Picture Book for Adults was performed at HAU in Berlin in 2010 and further performances were then scheduled for Switzerland and the Netherlands. After the HAU performances a review was printed that pointed out a similarity between you directing style of cutting up a picture randomly into fragments and the novels of William Burroughs. How do you feel about the way your works are received abroad?

One thing that impressed me among the reactions after the HAU performances was being told that the other Japanese performances at that festival by chelfitsch and faifai could be seen in the context of Japanese pop culture as seen from the West, but Penino’s work didn’t fit in that same context. And, although our performance was definitely of another cultural context from that of the West, it didn’t have the feeling of something exotic. I think they saw something universal in our work. This year it will be performed in Belgium and Germany. We are able to do this because we were able to have the set of stage art we made for the HAU production of Frustrating Picture Book for Adults stored at Groningen in the Netherlands. A lot of effort goes into creating the stage art for one of our works and the sets we make are not portable, which is a problem in overseas performances. So for each performance we have to go early and re-create the stage art. But it is possible [because the basic set of Frustrating Picture Book for Adults was stored for reuse], and working with local staff at each venue to re-create the fine details of the stage art is an enjoyable process for me.- The new work Extase that you presented at the 2011 World Theater Festival Shizuoka had a set where you built a huge ten-meter wall on three sides of the outdoor stage and in doing so created a man-made set that completely shut out the surrounding woods of the outdoor theater. That, indeed, is not a portable set.

That is true (laughs). After the disastrous earthquake and tsunami of March 11, I was tired of seeing images of what you might call the violence of nature. So this became a stage that started from the act of shutting out the woods. So when those light pink muscle colored walls are torn down, the play becomes meaningless as a work. It was a project where we were to do a residence of three months there and create a new work, but until I decided to build those walls I couldn’t come up with any idea of what kind of work I wanted to create. So, for the first week I was there in Shizuoka I just stared at the endless sky and woods completely at a loss. I didn’t know what to do, because no ideas came to mind. Then it suddenly occurred to me that it was because there was no frame. So when I decided to build the walls the things I should do became clear. I realized once again that because my roots are in painting, no ideas come to me until I see the canvas. Next I had to decide what color to make the walls. Muscle color would be good, I thought. As the actors to stand in front of the muscle colored walls I wanted old grandmothers. The grandmothers they got together for me were old and amateurs, so they couldn’t memorize lines well. But I found out that apparently they could sing. So, I thought the setting could be the playroom of a home for the elderly. In that way things came together through a process of elimination. But due to the limitations of the performers, it became a work where they performed without hesitation.- As our final question, would you tell us about the outlook for the future of Niwa Gekidan Penino?

I am always at a loss when I am asked this question because I really have no outlook for the future. I can’t think in those terms. Well, I do believe that I will continue creating art that respond to the time and situation. I really don’t care about the future. If I were to say one thing, it would be that I want us to be a strong company doing strong works. Really, that is all I want.

Niwa gekidan Penino

Kuroi OL

(Dark Office Ladies)

(Nov. 2004 at Nishi-Shinjuku 6-chome special stage)

Photo: Aki Tanaka

Tanino’s storyboard

Niwa gekidan Penino

Chiisana (small) Limbo Restaurant

(Apr – May, 2004 at Hakobune)

Photo: Aki Tanaka

Niwa gekidan Penino

Frustrating Picture Book for Adults

(Oct. 2009 at HAU Theater, Berlin, Germany)

Photo(s) by Tim Deussen, www.fotoscout.de

Extase

(Jun. 4 – 5, 2011 at Open Air Theatre UDO, Shizuoka Performing Arts Park)

Photo: Shizuoka Performing Arts CenterRelated Tags

Kuro Tanino

Creating illusionary spaces The world of Kuro Tanino

Kuro Tanino

Born in Toyama Pref. in 1976. Tanino is leader of the theater company Niwa Gekidan Penino (Theatre of the Garden Penino) and serves as its representative, playwright and director. While a medical student, he formed the company in 2000. In 2009, Tanino and Niwa Gekidan Penino were invited to participate in the 2009 “Tokyo-Shibuya” program of the HAU Theater ’s festival in Berlin, Germany with his play Irairasuru Otonano Ehon (Frustrating Picture Book for Adults) , after which he has continued to participate in theater festivals in Japan and abroad. March 2015 saw the premiere of his new play Käfig aus Wasser created in residence at Theater Krefeld in Krefeld, Germany. Tanino’s recent works include Chekov?! (2011), Daremo Shitanai Anata no Heya (2012), Okina Trunk no naka no Hako (2013), Tanino to Dwarf-tachi ni yoru Kantor ni Sasageru Homage (2015), Dark Master (2003, 2006, 2016) and others. Tanino’s play Jigokudani Onsen, Mumyo no Yado that premiered in 2015 was the winner of the 60th Kunio Kishida Drama Award.

Niwa Gekidan Penino

https://niwagekidan.org

Interviewer: Kyoko Iwaki