Kakushin Tomoyoshi Satsuma Biwa recital “Nagori no HANA ICHI KAN”

(Oct. 28, 2021 at Gallery éf Asakusa)

Expanding from Satsuma Biwa

The Thoughts of Kakushin Tomoyoshi

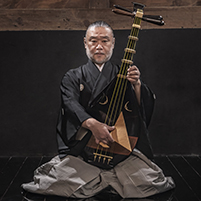

Born in 1965 in the Asakusa district of Tokyo as a grandson of Satsuma Biwa player Sokusui Yamaguchi and Kakushin Tomoyoshi. He grew up in an environment rich in traditional Japanese culture and performing arts, and learned various traditional arts including traditional Japanese dance from the age of three. 1984, he entered the Nihon University College of Art and studied Japan’s medieval performing arts in the theatre department. In 1987, he decided to become a performer of the Satsuma Biwa, as both of his grandfather were, and he studied under the master Kinshi Tsuruta. Since then, in addition to his activities as a Satsuma Biwa performer, he has performed with musicians and artists from various genres, including the rock group SeikimaⅡ, and in other activities he has recorded the first DVD of the Biwa Music Association based on a work titled Joheki no Hamlet (Hamlet on the Rampart), a newly written work by the novelist Osamu Hashimoto. Kakushin has also performed the Toru Takemitsu pieces Eclipse and November Steps with shakuhachi flute player Dozan Fujiwara. He is also active promoting the Biwa by teaching children, and has worked as an advisor on historical background of the traditional arts for historical TV drama series on NHK, Japan’s national television network. In other fields he has served as a music director and performer for computer games. He is recipient of the “Shoreisho” Education Encouragement Award of the Ministry of Education and the NHK Chairman’s Award. He is also a part-time lecturer for the Music Department at the Nihon University College of Art, and he serves on the board of directors of the NPO ACT.JC.

Kakushin Tomoyoshi Satsuma Biwa recital “Nagori no HANA ICHI KAN”

(Oct. 28, 2021 at Gallery éf Asakusa)

Exhibition “Biwa Meiki no Kazu Kazu” (Oct. 27, 29, 2021 at Gallery éf Asakusa)

*1 Satsuma Biwa

The Satsuma Biwa originated from the Biwa that was used by blind monks in Satsuma (present day Kagoshima Prefecture) and was adapted for use as an instrument to help in the intellectual training of members of the warrior (samurai) class with lyrics written by Jisshinsai (Lord Jisshin Shimazu) and music by the blind monk Juchoin (Ryoko Fuchiwaki). These pieces were written to convey the moral teachings of Buddhism and Confucianism in easy to understand terminology. But because the players were Satsuma samurai, as the times evolved into a period of civil wars. That time was the age of provincial wars, the content and expressive quality of Satsuma Biwa became increasingly valiant and heroic. With this, the influence of the ethical message of Jisshinsai, and that of the lyrical laments of women in lyric like “Xun yang jiang” of Bai Letian brought a tone of sadness to Satsuma Biwa music.

As for the musical qualities of Satsuma Biwa, there is a style of playing all the strings at a fast tempo and singing in an equally bold style called Kuzushi and a contrasting style of more melodic and sorrowful songs called Gingawari. What’s more, there is a type of full volume vocalization close to that of the Gidayubushi ballad drama that uses the full depth of voice from the abdomen which is different from the usual rather subdued voice used in most traditional Japanese Hogaku music. In this sense it is clear that the Satsuma Biwa music inherits a strong influence of the Martial spirit of the Satsuma warrior class.

(Eishi Kikkawa)

*2 Kinshi Tsuruta (1911 – 95)

Born in Takikawa city in Hokkaido, Kinshi Tsuruta was a Satsuma Biwa player and composer. She started the Biwa as a child through the influence of an older brother, and at the age of seven moved to Tokyo to study under the master Gensui Komine. There, she mastered the Kinshin-ryu style of Satsuma Biwa and began performing professionally and teaching younger apprentices from before the age of 20. Later, however, she turned to a successful period as an entrepreneur. Kinshi made her return debut as a Biwa performer in 1955. In 1964, she composed and performed her piece Dannoura for the Masaki Kobayashi film Kaidan (Ghost Story), and this led to her meeting the composer Toru Takemitsu. In 1967, she performed Takemitsu’s piece November Steps to international acclaim. In Kinshi’s ongoing quest for ever higher levels of deeply expressive Biwa music, she made revolutionary changes in the Biwa as an instrument and in Biwa performance.

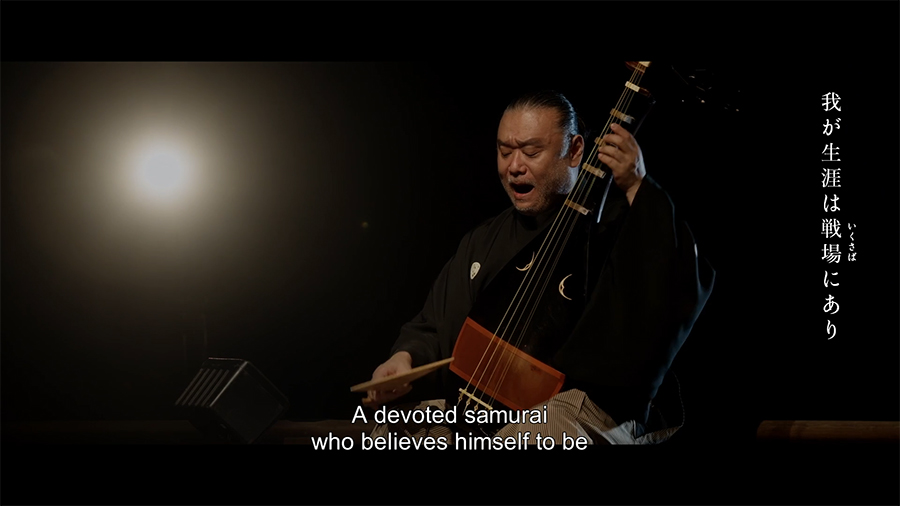

Nakamura Kazutaro × Onoe Ukon “ART KABUKI” Overseas Distribution Edition (2021)

Satsuma Biwa: Kakushin Tomoyoshi

https://md.jpf.go.jp/es/Actividades/Arte-y-Cultura/evento/322/art-kabuki-online

Related Tags