Involvement in multiple genres as choreographer and dancer

- With the new year only just begun, it is surprising to us that as of mid-February, you have already presented and performed in three productions: the Kyoto Symphony Orchestra Crossover “Ballet vs. the Orchestra” New Year Gala (composition, choreography, performer), the National Ballet of Japan’s Phoenix (choreography) and No Exit with Akira Shirai (choreography, performer). No Exit being a re-production as it is, in contrast to the first work, which focused mainly around dance, the provocative new production contained a lot of dialogue.

- These productions have coincided with each other but I was lucky enough to spend ample time in preparing for all of them separately. Jiří Kylián was known to say that creation of one minute of a piece, which took a whole day, was a job well done, and I abide by that rule (laughs). A lot must go into a piece before it can ever be choreographed.

- You involve yourself in a wide range of genres both as choreographer and dancer. Your appearances in archival works like the historic Japanese modern dance piece Fire of Prometheus (2016, premiered 1950), choreography by Takaya Eguchi and music by Akira Ifukube, and your collaborative works with Noh are good examples of this. It is obvious that there is a tremendous amount of research behind your works, constantly pushing the quality of the performances to their limits.

- The truth is that I do not frame things in terms of genre much. It is more like happenstance: I am fortunate to come across pieces I may be able to succeed at, at the right times. It was a coincidence, for example, that I was collaborating with Noh performers simultaneously in the 2017 Trilateral Arts Festival production A STONE (choreography) and as dancer in SAYUSA (Left-Right-Left *1) (direction). I was ambivalent toward it, in that I held profound respect for these traditional Japanese art forms, but also some resentment toward what I perceived at the time as an aloofness or inaccessibility in them. Dancing in Europe as I had been, I had become accustomed to the feedback that my performances were “in the style of Noh,” “like Butoh,” “like an exotic flower,” despite the fact that I was dancing much like those [non-Japanese] around me. This irked me, and I consciously avoided expressive elements that may be perceived as being Japanese in nature. On returned to Japan, though, I ultimately found these forms of expression attractive once again. It happened that I had the opportunity to speak to Yukiko Umewaka, the daughter of national treasure Minoru Umewaka, and to visit her home, which houses a Noh theater. A very agreeable person, I developed a very vivid relationship with Ms. Umewaka.

- And this encounter led to A STONE, which featured live Noh hayashi (instrumental accompaniment) in its telling of the story of Zeami. I just happened to be present at the initial meeting of the participating artists, and the atmosphere was tense. At one point there was a clear line drawn in the sand that some things just “could not be done.”

- From what I understand the Noh hayashi musicians (having no conductor) place importance on improvisation, which means that leading up to a production, there is no rehearsal of the musical elements in the performance. We were able to request the score of the flute part for ourselves, rendered vocally, in order to rehearse. We paid careful attention to this recording in choreographing our dance, and learned it virtually by heart to be able to react to any changes in the tempo during the actual performance. Our efforts seemed to draw the attention of the Noh performers, who offered to rehearse with the music “as many times as we liked.” I believe that it was a new experience for them to see the way these young dancers could meld themselves to the music quickly. As for the final performances, each encounter felt as though we were again meeting for the first time. For Sayusa, in which I participated as a dancer, musical director Genjiro Okura (shoulder drum) put forward many artistic considerations, resulting in an equally interesting process.

- We would now like to ask you about your personal background in dance. Did you begin with ballet?

- When I was a child, my father moved our family to Italy where he trained in violin making. Although I was too young to remember, when I was about three I saw people dancing on a television weather report program and I said to my mother, “I want to do that, too.” It wasn’t just exercise and it wasn’t eurhythmics, it was something unknown.

- People were dancing on the TV weather report show?

- They were (laughs). I couldn’t understand the words, but the feeling of the peoples’ movement was very vivid to me. I was rather slow at learning words, and just about the time I was learning to express myself in Japanese, we moved to Italy. Even when I felt that something was beautiful, I couldn’t express it in words. Words and language are supposed to connect people, but I got the feeling at an early age that they could also divide people. And I got the feeling that I wanted to devote myself to something that could enable direct communication with going through words.

- That was something you felt acutely as a child, didn’t you? Because you were at the age when you begin to build the connections between yourself and the world.

- Yes, it was. But I wasn’t allowed to study it right away. I would play records we had at home and dance with a stuffed doll diligently for two hours (laughs). I played Mozart and Bach and for some reason Mendelssohn, and I also liked music from northern Europe. Finally, it was at the age of five that my mother let me begin ballet lessons. We returned to Japan just before I would enter elementary school, but I continued ballet. But moving my body was embarrassing a young girl, stretching was embarrassing, and I disliked changing into leotards and going out on the floor to practice with all the others. So, I just clung to my chair and did nothing at the lessons, and then when I got home I would dance freely (laughs). I continued ballet until the age of 18, and in 1988 I won a prize in the Prix de Lausanne competition and after that I lived abroad.

- Did you have the feeling that you wanted to dance abroad from the beginning?

- In fact, my mother was against me doing ballet and she told me, “If you can’t do it on the international level, you should quit it right away.” But I also wanted to test my own capabilities, which is why I entered the competition. And I won the Prix Niveau Professionnel.

- At the time, there prizes that enabled dancers to study ballet abroad and the professional prize that meant a dancer had the level of skill to work as a professional in one of the ballet companies. So, that means yours was quite an amazing achievement.

- However, the prize didn’t include an introduction to join a specific company, so I just took the prize money and returned to Japan. Because I was still a high school student in a pre-collegiate course, everyone around me was preparing for their college entrance exams. Nonetheless, I had not yet decided what I was going to do in the future. It just happened at the time that the Jeune Ballet de France was touring Japan and I went to see their performance at Kanagawa Kenmin Hall. Regardless of the performance itself, it inspired me to see dancers my own age performing, and I got permission to join them in their morning lesson and quickly became friends with them. It just happened that one of the dancers got an injury that evening and it left them with no one who could do the grand fouetté 32 times as required in that repertoire. And since they were going to continue their tour the next day, I got a telephone call and I was asked, “Megumi, can you do it 32 times?” “Yes, I can,” I answered. So I joined the company the next day, just to do the grand fouetté. When they asked me if I could come with them to France, I relied, “Of course,” and that is how I came to dance in France.

- Are there so few dancers in France that can’t do the fouetté 32 times?

- It is not uncommon in Japan, but in Europe the educational system is different, so there are indeed fewer than you would expect. There are many dancers that have beautiful bodies and can dance contemporary as well, but they can only do about eight fouetté. So in the classes I instruct, I always have them practice the grand fouetté and tell them that it can be a key to success.

- After that you became a member of the GBF Youth Ballet company, didn’t you?

- That’s right. And it was there that I was able to join in the production of Quartet for the End of Time (Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps) by one of the leading choreographers of the day, Mathilde Monnier and contemporary music composer Olivier Messiaen, and become interested in creation of new works. The Youth Ballet company toured around France twice a year performing ballet. Sometimes we performed in gymnasiums and community centers and experienced things like having the children of a dreary coal mining town run after our bus seemingly forever as we drove out of town after our performance, and it was these kinds of experiences that got me interested in educational programs for children.

- But eventually injury would cause you to leave the company.

- I had an old ligament injury that I got in a ball game tournament in high school. In Japan, we only had lessons twice a week, but in Europe we worked seven or eight hours every day and I guess the load of that stress caught up with me in time. At the hospital in France they told me my ankle was one of about a 60-year-old, and that if I had waited another week I would have been unable to run for the rest of my life. So, I returned to Japan and had an operation on it.

- For rehabilitation you went to Ecole Superieure de Danse de Cannes Rosella Hightower ballet school, and after that you got contracts with the Avignon Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris and the Ballets de Monte-Carlo.

- Monaco is very close to Cannes, and I heard there would be auditions there, which I tried out for and got a contract. But it was for the summer of the next season, so in the meantime I was invited by the director to join the company in Avignon for half a year. The director was one of the finest technical trainers in France, so I was able to make a lot of progress in my spin and jumping technique there.

- Would you tell us how you came to move from Ballets de Monte-Carlo to the Netherlands Dance Theatre (NDT)?

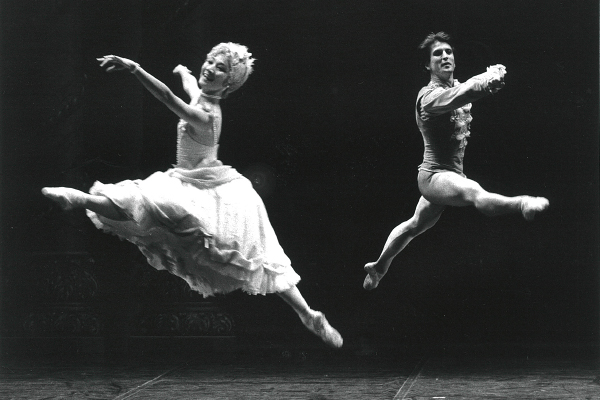

- At the time, the director at Monaco, Jean Yves Esquerre, was formerly of NDT (*2) and in their repertory were works by artists like Kylián and Neumeier and Forsyth. Several months after I joined the company, I had the opportunity to see a rehearsal of Kylián’s Verlärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) and was amazed by what I was seeing. There were auditions being held for NDT2 in a few weeks, and it just happened to be during the vacation of Ballets de Monte-Carlo, so I thought that I just had to try out (laughs).

- Kylián’s Verlärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) is choreographed to Schoenberg’s music of the same name inspired by Richard Fedor Leopold Dehmel’s poem that describes a man and woman walking through a forest on a moonlit night. What was it that impressed you so strongly about the piece after only seeing a rehearsal of it?

- Near the end, a man and woman are doing repeated rotational movements as their steps come together and separate utilizing centrifugal force as they turn, and with each rotation there is a progression into a new dimension. I love the dance of Ludmila Semenyaka, a former prima with The Bolshoi Ballet, and when she does a rotation it is as if the world of expression changes from what it was before each time. I felt that being achieved by the strength of the work Verlärte Nacht, and it made me feel suddenly that I had to see more. At the auditions there were hundreds trying out and it was overwhelming, but I was one of the four selected to be new members of the company.

- You were a member of NDT from 1991 to 1999. What were those nine years like?

- When I began dancing at NDT, Nacho Duato and Mats Ek had developed from NDT dancers into choreographers, and were creating works for the company. The company was in the midst of growing and it was giving work to talented young choreographers and nurturing them. Ohad Naharin had been very successful doing choreography for NDT before he went on to become artistic director at Batsheva Dance Company. It was tremendously thrilling to be a dancer then involved in the process of these people becoming successful as choreographers.

- What a wonderful list of great choreographers you have just mentioned. From then, NDT became a gathering place for leading talents in contemporary ballet and contemporary dance, in what was truly a golden era, wasn’t it?

- The years that I was there had indeed been a time when that golden era was achieved. Because Mats and Ohad, and of course Kylián, were choreographers who really dug deep into the depths of dancers to bring things out of them, there were also difficult experiences for us as dancers, but for that same reason they were also bringing out new discoveries for me and there were always new experiences.

It was also a time when, depending on the place, Kylián’s new works might be accepted or booed and reviled, and depending on the reviews that appeared in the newspaper the next day, the audience draw would be affected, so it was also a stressful time. They were hectic times when in New York, a performance one day at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) would be followed the next day by one at Lincoln Center, and in Paris, a Théâtre de la Ville performance could be followed by one at the Opéra National de Paris. - Were there any other Japanese members of NDT besides you?

- After me, Rui Watanabe and Shintaro Oue entered NDT2, but because the tours and working times of NDT1 and NDT2 were different, I had very little contact with them. So effectively I was the only one in NDT1 at the time. In my 20 years based abroad I very rarely had an opportunity to speak to anyone in Japanese.

- In those days, NDT visited Japan numerous times for performances. Especially impressive were the Saitama Arts Theater’s “Sainokuni Kylián Project (2000 to 2004). At the request of the theater’s director at the time, Makoto Moroi, there were programs like a residency for NDT3, and in 2002, a Japan tour by all three of the NDT groups, NDT1, 2 and 3.

- Seeing me performing in the NDT production of One of a Kind, Moroi-san told Kylián that he wanted me to perform a solo piece at Saitama Arts Theater. In fact, at the time that request was made in 1999, I had already quit NDT to begin working freelance, but Moroi-san kept the offer standing for me. But Kylián had said there were not many good solo works for women, so he was not very enthusiastic about the project. Eventually, however, Kylián said that he would choreograph one for me to perform. And the piece, which also included performance by Eri Matsuzaki, was performed in 2001 under the title Blackbird.

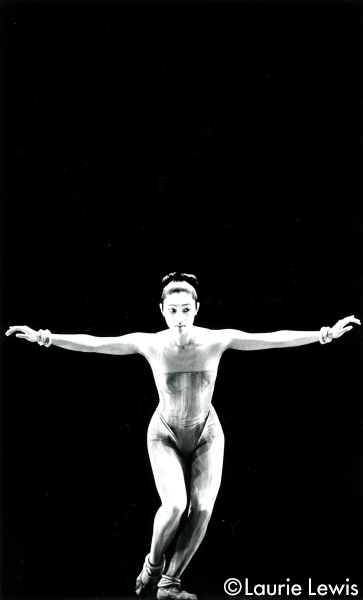

- Blackbird is one of the products of the Kylián Project. From above the stage, thin gauze tubes were hung and when you began to move around a woman in black appears and begins to cut them. From a speaker the audience hears Kylián reading from Becket or speak a narrative in a whispering voice while you dance out the story of a dancer’s life while your face or parts of your body are projected in the background along with video of you dancing with your NDT partner Ken Ossola. In the final portion, you leave the stage fully nude after a very moving performance and you have portrayed the life of the dancer and the god-like way in which the dancer dedicates herself body and soul to dance. The costume design was by the fashion designer Yoshiki Hishinuma. What was the creative process like for this piece?

- At that time I was visiting companies around the world to teach performance of Kylián works while also dancing my own performances, so I was working bit by bit in places around the world, devoting a lot of time to each work. Kylián had not done a new work for some time, but when he created the new work Click – pause – silence he felt good about it and began working on Blackbird in bits and pieces.

- When Blackbird was re-produced (2002) you were pregnant at the time and dancing with your abdomen bulging, which made a very strong impression. The hanging gauze tubes then took on the image of the birth canal or umbilical chores, which was powerful imagery. Was dancing like that a deliberate artistic choice of yours?

- I changed the choreography I dance from what it had been for the premiere performance. For a ballet company there is always the choice to have a substitute dancer perform, but since I was performing freelance under my own name at the time, I decided I had to perform myself, even if it meant crawling on the stage floor, and I learned a lot for that experience. Because one is performing with that determination, it is bound to convey something more, so it is important to think about what you intend to convey in a case like that. Because it is not only a perfectly danced performance in perfect physical condition that can tough an audience. So I have never cancelled a performance for a reason like that (smiles).

- By the way, in 2000, the year before the premiere of Blackbird, you choreographed and performed your own solo piece dream·window. It was your first original work and it won the Netherlands’ Golden Theater Prize.

- The work dream·window began from something I imagined when I say the gardens designed by the Zen monk Soseki Muso, who designed the famous gardens of Kokedera (Moss Temple) and Tenryuji Temple in Kyoto. There is a rock and a woman, and she sits on the rock and envisions it as a coffin or a gravestone. When I dance, something like an other self comes out of me, and in this piece the woman becomes what can be considered my other self, and she discovers in herself another self as the piece unfolds.

- After years of working on the cutting edge of the European dance world, you moved your base of activities to Japan in 2007 and began activities by establishing the project company Dance Sanga. Until 2014, you conducted dance research and experimental performances with your colleagues. What made you decide to move your base to Japan? And, what were the aims of you activities with the Sanga group?

- When my child reached the age of four and it was time to begin school education, I felt strongly that I wanted my child to be able to read and write and communicate with others in Japanese, and that is why I returned to Japan. That was the primary reason.

The Sanga name comes from the Sanskrit word Sangha which in the Buddhist context refers to the gathering of believers to eat and pray after the Buddha’s life in this world ended, and it was used in the meaning of a “place of beginning.” I personally wanted to return to a “neutral” state of myself, and to do it not alone but with a group of people. I began Dance Sanga with the aim of creating such a place. Soon after I started it, I was given a residency at Yokohama’s BankART NYK Studio 202. I was in my 30s and still young and I gathered a group of young dancers in their 20s and early 30s, many of whom had been active abroad for a while and then returned to Japan. The key words I used were to shave away the unnecessary so that I could always have access to myself in a neutral state, and I gradually created a [training] method for that purpose. - After returning your base of activities to Japan, you began to work actively and ambitiously not only as a dancer but as a choreographer as well on many works. One of the works was with the ballet dancer Yasuyuki Shuto. You have collaborated frequently with Shuto-san in the DEDICATED project series that he produced from 2011 at the Kanagawa Arts Theatre. How did the two of you first come to work together?

- I choreographed a work for a production of Cinderella (2009) by the Noma Ballet Company, and I was looking for someone to dance the part of the prince. Earlier I had seen Shuto dance in a production titled Perfect conception that Kylián had done for The Tokyo Ballet, and I had liked his work. So, I thought I really wanted him to perform for us, so I called him. I am a person who has only made a phone call a few times in my life, but that was how much I wanted his participation. At the time, however Shuto-san had quite the Tokyo Ballet and was taking some time to think about things, so refused my offer. But, about a week later I called him again and asked him if he would like to work with me on a different project. The result was a collaboration titled The Well-Tempered (2009), which was a duet piece using Bach piano music. And before we presented that piece, we danced a duo piece in an installation by Keiko Sato titled Toki no Niwa (Kanagawa Kenmin Hall Gallery). And that led to a duo piece titled Shakespeare THE SONNETS (2011, New National Theatre) inspired by a Shakespeare poetry collection.

- Could you tell us about Shuto-san, the artist that you have done these creations with?

- Shuto-san is a very mysterious person, and although we supposedly speak together about a lot of things in the creative process for our collaborations, the minute he stands on stage, I am so surprised that I have to ask, “Who is this person,” “I’m seeing him for the first time!” And I believe that Shuto-san you think you are seeing for the first time is the real is the real Shuto-san. No matter how many times I work with him, he never appears the same way twice. I think that is the biggest reason that I always want to work with him again on new pieces.

- I would like to ask what process your creative work follows. For example, what sort of process did you follow in creating the work Death – Hamlet dealing with the theme of death that you directed and choreographed for the 2016 DEDICATED series? The work borrowed on the plot of Hamlet with Shuto-san in the role of Hamlet and you in the double roles of Ophelia and Gertrude, with an ensemble of seven actors. The opening scene is set in a present-day museum, and as soon rehearsals began, Shuto-san said that you began saying, “There is a picture here.” Does a finished picture suddenly appear to you like that?

- Basically, the feeling is that I see scenes of a work that is already complete. But, as with dreams, there are many inconsistencies. And it is difficult to know how many of those should be left. Like a mandala suddenly appearing to your eyes, the feeling is one of the things I want to make suddenly coming to me.

- Is that true with your works based on plays as well as works based on music, such as The Firebird that you did for The New National Theatre Ballet Company (that drew notice for its stage sculpture with the appearance of a contemporary phoenix in high heals that seemed to pose questions of gender)?

- Yes, it’s the same. When a vision doesn’t come, I do more detailed research to broaden my perception and that is when a vivid image of what I want to do most will come to me.

- I once had the opportunity to do an article on the production Asleep to the World (2013) for which the music director was the improvisational musician Kazuhisa Uchihashi and the performers were Yukio Suzuki and Shintaro Hirahara. In m interview for that article, I was told a lot about the “half asleep and half awake” poetry of the legendary Persian mystic poet Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī that the title of the production was based on. I was told things like, “the human spirit awakes when the body is sleeping,” but I have to admit that I didn’t understand at all how that interpreted into dance. Since it would seem that dancers have to be given specific choreography to dance, how do you communicate such things?

- Well …. With regard to the body’s range of motion and dynamics, there are truly a wide range of techniques for choreographing and ways of communicating things. But, when you are creating a piece, it is a fascinating fact that you can never repeat movement that you have done when you are told to improvise and just move intuitively. Still, when you have movement that you arrived at intuitively during the creation process, there is a need to analyze that movement and fix its definition if you are going to give it to a dancer as choreography.

- In other words, choreography is the process of analyzing and fixing the definition of movement that occurs intuitively on the base of a dancer’s highly developed skills?

- Of course there are many methods of choreography and, depending on the individual artist, that which they call choreography may differ completely. In the Netherlands where I was active for many years there were conservatories and academies of dance and they had different approaches to choreography, and the characteristics were different. The Royal Conservatory in the Hague teaches old ballet strictly according to traditional method, but the Academy in Rotterdam is led by people who work according to the Cunningham system and its basic technique, to they are good at introducing new experimental things in their works, while the Academy in Amsterdam for example has the philosophy that it is not good to be bound by a specific base of technique, so they promote a “non-dance” approach. Since the Netherlands is a small country, these different schools competed with each other, and that made it a very interesting place for dance. The non-dance people criticized us for being bound by technique.

- Even the people at NDT were criticized for being bound by technique?

- Yes. But there is no way I could pretend that the ballet I had been learning from the age of five never existed, could I? In particular, the ballet I had studied early on was strongly influenced by Russian ballet with its strong emphasis on the details of style and aesthetic beauty. So, once you have input that kind of style into your body, it is difficult to erase, and perhaps it is difficult to respond differently. I like the Bolshoi Ballet Company very much, and I had shaped my skeletal structure and musculature all for that style of ballet. The path that I would pursue had already been built into my body, and I sensed that I my potential on the skeletal and muscular level was already limited. Of course, in order to dance ballet repertoire of the old aesthetic style absolutely requires that kind of ballet technique. When I danced the choreography of artists like Ohad Naharin, there were times that I felt my ballet training was a hindrance for me in moving to a new level of movement. So, just after I went freelance, I feel that I was headed in a direction in which I would dismantle and negate the ballet background I had acquired and create new works and forms of dance expression that would not depend on it. While in Europe I had done my best to avoid being seen to have an oriental appeal in my performance, but when I returned to Japan the critics would say I have aspects that are not Japanese, so what can I do (laughs)? But lately I have made peace with those things that I had forbidden myself to do and I am now able to deal with things on a single plane. Dispensing with unnecessary preferences or principles, I am now able to humbly bring the best of my resources that each different work demands.

- ”Made peace with” is an interesting expression to choose.

- One big opportunity came with the job I undertook for the year-round educational programs that are conducted at the Red Brick Warehouse No. 1 in Yokohama. At the end of that year, I presented my work Silent Songs as a culmination of the program. It was a piece with one portion that speaks about the history of dance, and I studied a number of things for that. I want to be able to communicate something about what might be called the spiritual heritage of dance that the human race has compiled since long ago and the ways it is present today, and I have come to feel that it is an important mission of mine.

Of course it is possible to view films of old dance. But, for example, like the way we can see the geological strata piled up from the past when we cut a cross-section of the ground, I think it world offer a tremendously rich experience if we could show how the history of dance is engrained in the movement of a someone dancing in front of you now. Think about that, it seems foolish to stick to a limited set of preferences and principles. Because I want to learn more, and there is an almost unlimited array of dances in the world that I want to know about. - After the career that you have built, I think is fantastic that it has led you to a point where you want to learn about a wider world of dance.

- No. It’s just that I’m slow (laughs).

- The work Triplet in Spiral (2018) that you wrote, directed, choreographed and performed in also had Ryohei Kondo (choreography, directing) and other young ballet dancers performing in it, and it appeared to be a work that you created for young people. Are you interested in nurturing young artists?

- For the longest time my only concern was my own dancing, and I was never in a position where I was doing any teaching. When I was about 27 at NDT, I had a class to teach for the first time when we created a piece for a theater in Brandenburg, Germany, and I think that was my first experience of teaching. When I was about 29, I did things like instructing workshops at the Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater, and I was also going to ballet companies around the world to teach them to perform Kylián pieces. Kylián’s works may appear to be close to ballet, but actually they are quite far from ballet. So it required that I do some research to figure out how to teach the difference in the bodily movements required. So, at first it was more a case of coaching with professional dancers rather than actually teaching people to dance

The turning point came when in my early 30s I started coaching 17 or 18 year-olds who were competing in the Prix de Lausanne. I would have them dance and then offer them advice for raising the level of the dance in the final stages of their preparation. It was from that experience that I became interested in the teaching young dancers from the early development stage. When I returned to Japan, it was with the idea of doing both creation and educating dancers, including the intuitive and technical aspects, like the two parallel wheels of a car. It was with that idea that I wanted to start the Choreographic Center. The fact is that Triplet in Spiral was the starting production for that. For the performance, it was Miu Kato that I selected from the audition participants. She was the kind of new talent that I wanted to find. - That was a big decision that you made. What was it that led to such a step?

- Around the age of 30, I repeatedly had dreams where I was told, “Until you get into education, nothing new will start.” (Laughs)

- Was that a revelation?

- When I looked back on my life, the feeling was one making a journey in a small boat in the great expanse of sea. I wondered if my compass was working right, the map I was following correct; I couldn’t even answer those questions. I was adrift among storms at times, and sometime the water would dry up, and I felt I had no shore to reach. But when the time was right, I knew there would be ports that I could depend on. At times it would be a theater, or a choreographer or my friends and family. I believe that there are a variety of “ports” like that on different levels where I could stop and breathe for a while, get new information and clean water to drink, and then sleep on the land. And when it was time to depart again on the journey I would have the latest map and a compass I could trust. Although I am still on my journey, I thought that I wanted to create a “home port” for young people.

- Please tell us of your plans for the future. Could you tell us something you are planning, even if it is just a, “best case scenario?”

- It is in the dancer’s disposition to harbor an inner struggle, and, equally, in order to accomplish things out in the world one also needs others to work with. At our Choreographic Center we place an emphasis on developing a rapport between artists and producers, and that the relationship then serve as a foundation on which projects are built. My vision is for the Center to serve as a base from which dancers can develop themselves freely without feeling unduly worried, and that it be sufficiently equipped and organized to allow artists who come there to embark on their next journey, like a dependable port. So, it will be a metaphorical “port.”

Practically speaking, we want to offer training and career development support to dancers with a focus on the performances, as well as provide resources for research on the larger performing arts scene and archival work on dance. The nurturing of choreographers would be another goal. We are trying to develop a place where there is an open exchange on how professional choreographers and emerging choreographers from abroad develop their projects, providing hands-on experience in the process of collaborating with a dramaturge to compile pieces as well as attending to the various details that should be addressed before a work is finally presented to an audience. I think it would be great, for example, if we could present works by up-and-coming young artists alongside critically acclaimed historical works, and provide a platform for younger artists to plan and create works.

As a lead-up to the establishment of the Choreographic Center last year we produced a performance of Triplet in Spiral, and as the Choreographic Center, we hosted Miki Orihara (residing in NYC) as guest lecturer. Orihara is knowledgeable on the Graham Technique, having studied under Martha Graham directly. She accompanied her explanations of Graham’s work with the actual movements, and we found this very instructive. I believe it was a lecture with a great amount of reach, dealing with music, the relevant political issues of the time, stage art and lighting through the lens of Graham pieces. Lectures such as these can educate not only dancers but audiences as well. I would like for the Choreographic Center to be a place where one might discover the breadth of the art of dance, from traditional Japanese dance to hip hop to tribal dances of Africa. - Are you going to be teaching there yourself?

- Right. And to do this properly I need to define upon my own dance method. It must have both movements based on ballet training, and those that do not. I happened to read a treatise on singing, once. It described how in Italy, instruction had traditionally been separated into two categories, notes that could be sung within one’s normal vocal range, and those that could not. These were then combined, retroactively. Such an approach has been deemed too time-consuming, and today they are taught together from the start. The treatise concluded that because a combination of the two voices had become default, it placed a limit on the potential of vocal expression.

This spoke to me deeply. There is a similar phenomenon in dance. Ballet movements should be practiced every day as such, and expressions which ballet alone do not allow must be learned in addition to this. Competence in ballet is the fundamental requirement. From there, my own background includes training in the Limón technique and the methods of Ohad Naharin and William Forsythe I have done since I was young, as well as other elements like Yoga and Tai-chi that I have found to be important. I have built a method of my own that draws on all of these elements. Unfortunately, I cannot claim that I can lay this out as one single coherent method, at present (laughs). - Perhaps you might refer to it as Naharin has described his Gaga method, as a method something that is “continually being updated.”

- Yes. Although I am not a ballet teacher, I want to provide dancers with a neutral and orthodox base in dance; because the orthodox part is the most difficult. Although it is very rare in actual stages for everyone to go out and dance in toe shoes, I believe it is important to teach the fundamentals of ballet. For example, while the Alexander Technique doesn’t connect directly to any form of dance expression, it gives dancers a base for dance, and actors a base for acting and people who aren’t engaged in any form of expression a sense of the body that will be very useful in their lives. Feldenkrais method or Gaga also have that aspect. Which means a method doesn’t have to be directly related to a particular type of output. So, I believe that sort of solid ground from with rich things can be grown is an important aspect of a method.

- I think the idea of a method that is not meant for dancing classic ballet but as a technique for living a better life is very impressive. Where is your Choreographic Center based?

- The location takes THE STUDIO (*3) as its base to begin with. The locations for performances are not always theaters, and we are looking for places that can be used well and carefully. And, we intend to look carefully for supporters.

Today there is plenty of information available and it looks as if we will have free choice regarding our future course, but the possibilities for a dancer’s future are more limited than one might think. So it comes down to winning a prize in a contest or a chance to study abroad. Therefore, many young dancers are uncertain what course to follow. So, at the Choreographic Center I want us to be able to serve as a home port where we can make careful use of the experience of numerous people with careers in dance to help in young dancers’ choices. Since there are some who learn with their physicality and some who learn with their minds, I hope we provide a selection of resources from which they can make their own choices. Although it may be small in scale, that is the kind of place I want to build. - That sounds wonderful. Though ideally this is work that the national government should be undertaking.

- But, I also think that if there are people who can do it, it is a good thing if people like us can work on a small scale when the chance is there. There are things that can only be done if you have the freedom to act and there are many things that can’t be done with a structure that is too large. So, we will be doing what we can, little by little.