- You began studying butoh from 1997 at Asbestos-kan. Therefore, I believe that is your point of departure in dance, but were you involved in any other types of dance before that?

- Up until high school I played soccer and was totally involved in sports. I was born and raised in Shizuoka Prefecture and moved to Tokyo in 1990 to attend college. My first big encounter in Tokyo was film. I became absorbed in the movies of Shuji Terayama and David Lynch and movies like Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas. I wanted to try shooting a movie of my own, but I knew that would take a lot of money. Instead I entered a small theater company with the intention of becoming an actor, which was something that required no more than one’s own body.

I did theater for about two years but I found that I had an ongoing discomfort with saying my lines. I was especially uncomfortable when we would do practice sessions where I had to improvise lines spontaneously, and I couldn’t do it well. To begin with, I am not a person who speaks easily with people and I always felt embarrassed when the script called for me to shout out dramatic lines.

It was then that a colleague in the company told me about this awesome art form called butoh. I had no idea what butoh was at the time, so I found a performance and went to see it but there was nothing interesting about it for me at first and I wondered what was supposed to be awesome about it (laughs). But among the leaflets I got at that performance I happened to see a notice about a workshop to be held at the Asbestos-kan and I thought that maybe if I used that to test myself I might find out what was so awesome about butoh. So I decided to attend the workshop.

The workshop was planned as a two-month series of sessions taught by different butoh artists. I was taught by Kazuo Ono, by Yoshito Ono, by Akira Kasai, by Koichi Tamano and by Moe Yamamoto, and all of them had their own distinct style and character. One after another all these famous butoh masters came to Asbestos-kan to teach us. In addition to the butoh masters we were also given a photo workshop by photographer Eiko Hosoe. - After [butoh pioneer] Tatsumi Hijikata’s death his wife, Akiko Motofuji, began the “Karada no Gakko” (School of the Body) that you took part in. The classes were conducted in small groups with a wonderful slate on instructors, not only from butoh but from different genre as well. While Hijikata was still alive, he seemed to dominate the atmosphere at Asbestos-kan as the king of butoh, but when Motofuji took over after his death the style became very open, I believe. And that is the atmosphere in which you had your first real encounter with butoh, wasn’t it?

- I experienced butoh at that time and found the fascination in using the body. Everything about that experience was fresh and new. With ballet, for example, you may think it is a wonderful art, but it is not something that you can just do and pick right away. Butoh is different, however. With butoh, all you need is your body. If you want to use your voice, you can use it. Eventually I quit college and continued to go to Asbestos-kan to study while working part time. That was in 1997 and ’98 when I was around 24. I tended to be reclusive when I was in college, reading books all the time and was something of an egghead. People in butoh have a tendency to be very careful and serious about their use of words, and I felt that when I was using my body in butoh it helped me achieve a solid, balanced relationship between words (the mind) and the body.

- That was where you also began to experience performing in front of an audience, wasn’t it?

- I was able to perform in a lot of Motofuji’s works. It happened to be at the time of the 30th anniversary of Tatsumi Hijikata’s death and there were performances at the Mito Art Museum and the Aichi Art Center that I performed in. Motofuji, Kazuo and Yoshito Ono danced the main parts while the rest of us appeared on stage like objet or in short group dance parts. We did a variety of things, like just standing there bare-bodied or just jumping (laughs).

After a while we students began doing our own small productions and performances. For those performances I began creating my own short pieces. After that I also participated in performances by groups consisting of dancers who had formerly studied at Dairakudakan, such as Daizuko Farm, SAL VANILLA and YAN-SHU. That is where I first experience the Dairakudakan style of practicing (training) butoh, and it was another form of culture shock for me. - In Dairakudakan style butoh, works are created from the base of some very strictly defined forms. It must have been very different from the butoh you learned from Motofuji, Kazuo Ono and Yoshito Ono.

- Yes. There was more concern with “forms” and more group dance than what I learned at Asbestos-kan. At first I was often told, “You certainly an Asbestos student.” That was a big complex for me at the time and it made things hard for me. However, gradually I learned the joys of the new style and there was a time when I actually wanted to join Dairakudakan and study there for a while, but someone told me, “You are too impressionable. It is better that you not go there.” If it wasn’t for that bit of advice, I would probably be dancing as a member of Dairakudakan today (laughs).

- Having learned what could be called “butoh” from a number of different teachers, when was it that you became aware that you wanted to do your own creative works within the genre of butoh? And what were the circumstances that turned you in that direction?

- The people who have studied at Dairakudakan have a saying “one person, one school [style of dance].” They all have the idea that eventually they will become independent and pursue their own style of expression. When I was performing with SAL VANILLA, they told me I could use their group as a springboard for pursuing my own creative work. So while I was performing with them I also began to perform solo pieces of my own. I began doing that regularly from about 1998, and in 2000 I asked some friends to join me to start a new company that we named “Bulldog Ekisu (extract/essence).” The member were people I had met at Asbestos and former Dairakudakan people I had worked with. It was like people saying “Let’s start a band!” (laughs). It was that kind of spontaneous momentum that we wanted to start a group to pursue our own forms of physical expression. At that time I had promised myself that I would do one group production and one solo work a year. And ever since then I have maintained that pace of performances of my own works.

- At that time, did you consider what you were doing to be butoh?

- To tell the truth, I didn’t know at the time that butoh was a form of dance (laughs). I thought that butoh was butoh, dance was dance and theater was theater. But when we went overseas we were called butoh dancers. Gradually I realized that butoh was a form of dance. When I first started butoh I was satisfied with the idea that we simply whitewashed ourselves and became butoh bodies [through our training]. However, I gradually came to feel that I wanted to dance my own form of creative dance. So, when we started Bulldog Ekisu, I didn’t use whitewash, I danced in regular clothes and in a style that was completely different from butoh. But since the audience was always our butoh colleagues, they’d say, “What is this supposed to be?” They didn’t understand what I was trying to do.

- I was watching all the ST Spot performances around that time and I felt that what you were doing was neither butoh or modern dance, but perhaps something closer to the early post-modern dance that was being done in America in the early 1960s, or perhaps something you could call a rather “cool” form of movement. Even though you had been doing butoh, was there something that caused you to reach a point where you would not be satisfied with that anymore?

- The first person to start what we call butoh was Hijikata, but in fact he already had a body that had been trained in modern dance and his butoh was built on top of that. In my case, however, I realized that I had been trying to do butoh with no prior training or ability to dance, and I began to wonder if that was really acceptable. So, I decided that I should begin again by studying dance for a while, and for about a year and a half I studied a variety of different genre, everything from the basics of ballet to hip hop to Tai chi. At first I entered a ballet class that turned out to be one for fairly advanced dancers and the teacher realized immediately that I was a complete beginner and said, “What is he doing here?” (Laughs)

- That is certainly an episode that shows how ambitious and serious you were (laughs).

- I realized my mistake and got out of there fast (laughs). Ballet is absolutely something I am not capable of, and for that reason it was the most interesting of all. It gave me the opportunity to focus on every part of the body [and their movement].

- Although your involvement in dance began from butoh, today you are thought of more as a contemporary dance artist. What was it that led you to begin creating pieces that were closer to contemporary dance?

- It was when I entered the ST Spot “Lab” program with a solo work. This is a program ST Spot holds every year with a different curator each year as director. I entered in 2002 with a solo piece when the curator was Kota Yamazaki and with a group work in 2003 when Zan Yamashita was curator. That work won the Lab Award and gave me the opportunity to participate in showcases, where my works could be seen by a different audience.

That was a time when I had a feeling somewhere inside me that I wanted to get rid of everything butoh-like in me and, instead, try things like using the body [movements/presence] of amateurs. At that time I also changed our group name to Kingyo (goldfish). The reason for that name was simple: I wanted to keep goldfish (laughs). Goldfish have a cute image, but in fact the more expensive types that are called beautiful actually have a rather grotesque appearance. So the name bears the nuance that values vary with the eyes of the beholders. - It was also around that time when you met Ko Murobushi, wasn’t it?

- I had seen the performances of Ko Murobushi several times, but I had never actually met and spoke with him. The first time I spoke to him was at a performance in Mexico in September of 2003 when he approached me as a dancer. From a point where I was trying to separate myself from butoh, this encounter made me think about giving it one more go from a new standpoint. Meeting and speaking to Murobushi there in Mexico let to creating a new piece, which we did in ten days. After returning to Tokyo it was developed into the Ko & Edge Co. work titled Bibou no Aozora (Handsome Blue Sky).

Murobushi taught me about the possibilities of butoh and about how to use the body and he made me want to make another go with the task of doing the kind of dance that shows the body. I had grown to dislike very much my body that had come to know butoh, but this encounter with Murobushi made me think again and come to believe once again that there were things I could do with it that an amateur’s body couldn’t. - The work Yaguka-yaguka ah… that you submitted to the 2005 Toyota Choreography Awards and won the audience-balloted “Audience Award” with seemed to be one that, for better or worse, had almost no remnants of the butoh you had done up until then. I took that as a positive trend because it seemed to show your point of departure with group works, without relation to either butoh or contemporary dance. It would seem that doing group dance works would be very difficult for someone like yourself who had done primarily solo pieces in small performance spaces until then. How did you create that work?

- It may still be the same now, but I believe it is a work that shows clearly my intention to create a state of chaos. It may not be what you call a happening, but it is a work with a lot of people coming and going onto the stage. It was an attempt to explore the interesting possibilities of staging (directing) rather than the strengths of the dancers’ bodies per se. Like the work I won the Lab Award with, I used interesting people I knew around me, like a person who was doing performance, a comedian and a chiropractor who also did karate. I wanted to show the interest of having people with a variety of different kinds bodies performing. However, because these were not people who are doing dance regularly, it is a style that is hard to continue.

- At that time, did you begin to find an interest in being involved on the directing side rather than always dancing yourself?

- Also, with that line-up of performers, there were times when I tended to stand out from the rest [as the only real dancer]. Considering that fact, it was a time when I was thinking that it would be better for me to concentrate only on directing.

- You took the title for your work Chinmoku to Hakariaeruhodoni (Confronting Silence) from the book Confronting Silence ( Oto: Chinmoku to Hakariaeruhodoni ) by the composer Toru Takemitsu. Were you influenced by Takemitsu?

- I haven’t listened to the music of Takemitsu, but in his books we find writings about all the qualities an artist needs. When we read him we find so much to identify with, and that is what influenced me.

- Takemitsu’s is wonderful writing, isn’t it; like the sound of music flowing. The title Oto: Chinmoku to Hakariaeruhodoni in the original Japanese is phrased in a way that would not occur to one normally. Hijikata created a revolutionary work that used the title of Yukio Mishima’s novel Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors) directly, and that became one of the pioneering works of butoh. In your case, how do you link your titles with your dance works?

- When creating a work the title is extremely important, and when the title is a solid fit the choreography comes together with no wavering or uncertainty. For me it is very important a title I come up with holds strong and rings perfectly true.

Takemitsu’s title Oto: Chinmoku to Hakariaeruhodoni ( Confronting Silence ) implies the tremendous awe or weight of making a single sound, and in dance I think the same concept applies. With the same feeling of weight involved before Takemitsu touches the first key on the piano, the same thing happens in dance, I believe. I wanted to think about the feeling that should come before making the first move in dance, rather than just stepping lightly into it. I think that is why my piece Confronting Silence has a good number of intervals [between movements] in it. - In Takemitsu’s music, there is as much profound tension when no sound is being made as there is when there are sounds. That means that there is as much being said in the completely silent moments as there is in the moments when there are reverberations of sound. It that sense, it seems that your works have received positive inspiration from Takemitsu.

- The period when I began to work with Murobushi was a time when I was once again confronting the question of what the body is. I decided to work with the people I was involved with around me to work on the question of what I wanted to do in dance with a small number of people. I wanted to search for methods to show things with strong bodies, and I also wanted to search for myself. I feel that it was these directions that led to the recent work I have done.

- In other words, while on the one hand being influenced in various ways by Murobushi-san, you were also searching in directions different from him?

- I believe that the people of Murobushi’s generation have a very strong spirit of opposition to established ways. And I believe that they have continued to pose questions for themselves based on the belief that butoh is absolutely not dance. But my generation believes that it is alright to consider butoh a form of dance. If we don’t think and work that way, there is no reality for us. On the other hand, there is also the danger that such thinking can easily lead to a state where people believe that anything is acceptable.

- In other words, you want to value the special butoh concern for the body while at the same time wishing to see dance through a larger perspective, not confined to butoh. Is that correct? Is Confronting Silence a reflection of this?

- That’s right. I don’t know whether it will continue to take this form, but there was something I was experimenting with in this work. But there are also other things I want to try and I don’t feel any need to define a single style for myself.

- I would like to ask you now about how you work in the studio. From seeing your works I would imagine that your creative process is quite different from other choreographers who work up their pieces in the studio. Could you tell us about your process when creating a new piece?

- First I think about how the movements in a new piece will connect and once I have more or less conceived the structure of the entire piece I take it to the studio to try it out. In the past I used to go off in the hills by myself and practice movements as I walked. It would look strange if people were to see me (laughs). In an effort to save time, and because there are not many people involved, when working with the dancers in the studio stage I make drawings. They are very simple notifications of how the movements of the piece proceed, the positions of the dancers and images of what I want to do in each scene. In this way I communicate what I want to do in the piece in general, but I don’t think it is fully understood in this initial stage. In my mind as well, it is still just in the drawing stage and I don’t fully understand what it will be like. It is only by putting it into actual movement that I come to fully understand it.

- I know that recently you are also asked to serve as instructor for many workshops. What do you do in your workshops?

- When working with participants from the general public, I start by having them play a game of tag while holding hands with a partner. Holding hands builds familiarity more quickly than self-introductions. Next we do a game in which the same partners pull against each other. But it is not just a pulling game, I add an aspect of imagination, such as having them imagine that they are pulling for their lives at the edge of a cliff. That produces a desire not to fall over. But because they are being pulled they will fall over, but the desire not to fall creates a momentary slip in the flow of time. Creating this slip in time is an important part of my workshops. When time slips, a slip in space also occurs. And we do it to the point where the participants actually fall.

Since falling over is not something people normally do in their daily lives, the act of falling teaches us new things about our bodies. Next I might tell them to do things that make them focus on the “inside” of their bodies, such as imagining that they are being pulled from their stomach, or from deep inside their ear. Being pulled from the shoulder and “being pulled from a bone inside the shoulder may look the same, but the physical sense it gives is slightly different. In these way I get the participants to being concentrating on the outsides and insides of their bodies and their breathing. Having them think about opposites like outside and inside gradually gets them thinking about the entire body. This is a process that I take time to play out over the course of a workshop.

Also, no matter who the participants may be, I make a point of communicating things through words as much as possible. The things I want to teach may be things that I have learned over time by watching and borrowing from others, but a workshop is usually only a week long at most. So, if I simply use the old method of going through a movement and telling the participants, “This is how it’s done,” doubts will still remain in them and in myself. But if I make a point of communicating what I am doing in words, that relieves the doubts of the participants.

For example, there are often cases where people who want to dance will get into a state where they want to dance so much that they can’t stop themselves. When that happens, many dancers will tell them they should introduce more intervals of pause, but they don’t tell them how they should find the intervals within themselves. It may be good for people to find their own answer through trial and error, but there are many people who never find an answer. When that happens I will make an effort to make specific suggestions of things they might try. - It is very interesting to hear you talk about your workshops. It gives us a glimpse of what the body and the intervals of pause mean in your dance. I happened to notice on the Kingyo (Goldfish) website mention of “documentary type directing and choreography.” What does that mean?

- There was a period when I was debating a question of reality within myself, whether it was OK to allow myself to actually enter the realm of dance or whether I should stop one step short of that. I also think about the human relations involved between people in a group dance work and I used that expression because I want to pursue reality and a documentary type approach in my works. The slightest of things can cause gaps to form in human relations. For example, if feelings are too strong they can throw things off course and lead to violence or extremism. Lately I want to get away from this focus and do other things, but when it comes to group works, one can’t help but be concerned about the human relations aspect.

- When you are working in the studio, do you use images of those moments when a “slip” in time or a “gap” in human relations occurs in your body movements or simulate them in your mind?

- In the beginning, I had the idea in mind that it would be interesting if that happened. But when you actually try to do it that way in the studio, it isn’t interesting at all. Because of the difference between what one imagines in the mind and the body’s actual physical expression, you have to experiment thoroughly in actual movement to find how to express it with the body. Sometimes things like dramatic pause are necessary.

I am often asked if my dance is improvisational, or how much of it is decided (choreographed) in advance, and the answer is that it is decided (set in choreography) to a large degree. A great deal of studio practice is necessary to make set (choreographed) movement look like improvisation. Although the movements are decided, you mustn’t let the dancers move like they are going through a set of defined movements. To achieve that, I keep telling them opposite things, I keep them in confusion searching for the answer. But at the same time I keep telling them to follow the choreography, which puts them in a tough position; and I do feel sorry for them (laughs). In the process, another type of positive interaction is born within that confusion and struggle, and it shows [the viewer] their searching and doubt in a positive and skillful way. - That seems to me to be one of the most appealing aspects of your works. From the beginning to the end of the work you avoid showing any signs of it being a usual dance work where the dancers are actually dancing (choreography as “dance” for the bodies (dancers) involved). Instead, we get the impression that you are choreographing the performance space as a whole inclusive of the bodies of the dancers, or you might say that we feel your sensitivity to the space throughout the work. I feel that in Confronting Silence and also in Kotoba no Saki (The Point of Words) and Yaguka-yaguka ah .

- In my mind, I have a sense that the choreography doesn’t matter. What matters is that the scene isn’t complete or successful unless a person (dancer) is there in that particular place at that particular time, and if the person is there, things come together successfully. So in that sense, I am using people like objects, and there are times when I am using them like elements in the composition of the stage art. There are “absolute positions” or points that must be filled in the compositional sense, like in a picture. I absolutely want the dancer to be in that position at that moment, and you could say that that is the reason for the choreography involved.

- So, that must be why we, the viewers, get a strong impression that it is not a dancer occupying a certain position on the stage but a human being existing there. That may connect in some sense to your choice of the word “documentary,” but in any event, it seems to me to be a skillful device for not letting things appear to be intentional manipulation.

- I do indeed make considerable effort to avoid letting things appear overly intentional and thereby manipulative. If I just let the dancers go through a [choreographed] piece copying my own body movements, it ends up being nothing more than my own movements. Therefore, we spend a lot of time using the dancer’s own body in the studio to find the nuances of movement that are best for the particular dancer’s body, the movement that the individual dancer is able to do most naturally.

- Your recent work Love vibration is a collaboration between a violinist and you dancing solo. In that piece the violinist was not merely an accompanist but performed with virtually the same level of presence on stage as you, the dancer. What made you decide to do such a collaboration?

- I was asked to participate in a project in which the dance and the music would be created together from the initial creation stage of the work. I had never worked with violin before and the possibilities of a one-on-one work between two men was also interesting, so I decided to accept the offer. The violinist was a person I had never met before and we were brought together for the first time at a retreat to create the work. It is not easy to spend that much time together working with a person from another genre, but I realized this time that doing so expands the possibilities tremendously. So, if I have an opportunity like that again, there are many things I would like to experiment with.

- Your latest work Kotoba no Saki (The Point of Words) appears to be a work in which your concern for the body until now comes out more prominently than in previous works. Like a “straight ball” pitched by Yukio Suzuki. Can you tell us about this work?

- This is a work that I did out of a growing desire to choreograph more completely for the body [movement]. But I still find that when you move the body, words also follow of necessity. So, it made me feel that I wanted to arrive at a good-feeling balance between “words” and “using only the body” and going back and forth between the two. I don’t want to be an egg head and I also feel that it is too simple just to say that all I need is the body—but it still hasn’t reached the point where I am satisfied, so I want to try again using more dancers in future works.

- It did feel like a work in progress that could be developed into even stronger works with greater resilience, so I really look forward to seeing what you will do in your next attempt.

I believe that you have reached a very productive and fulfilling period in your career. Can you tell us something about your vision for the next year or two? - What I want to work on has become very clear to me, and as a result I have largely concentrated on the body, the body and more body for the past year or two in a pursuit of myself. And with the creation of Love vibration and Kotoba no Saki I think I have seen, or reached a bottom point, and in doing I feel that I have cleared on question I had been working on. Next, I want to try working again with more dancers. Now I think I am ready to show another aspect [of dance and composition]. It may be a reaction to the period I have just been through of an internal pursuit of the meaning of the body, but I am interested now in the external elements of space and time.

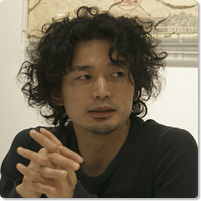

Yukio Suzuki

The new realm of contemporary dance pioneered by Yukio Suzuki, an inheritor of the compelling body movement of butoh

Yukio Suzuki

Born in 1972. Suzuki studied butoh at the Asbestos-kan (Asbestos House) from 1997 and danced in the works of Ko Murobushi and other artists. In 2000 he started the group Kingyo. He gained attention in the dance world for his documentary-like style of directing and choreography that uses compelling placement of dancers with a strong emphasis on their physical presence. In recent years he has expanded his activities as a choreographer with projects like choreographing for dancers of the Tokyo City Ballet Company and participating in the Asian Dance Conference. He also conducts workshops based on butoh methodology. With a highly sensitive consciousness of the body, he conducts programs around the country aimed at creating dancer-specific works. In 2003 he won the ST Spot Lab Award. In 2004 he participated in the final Next-Next program of the Saison Foundation. In 2005 he was the Session House resident artist. In 2007 he was nominated for the Kyoto Arts Center Performing Arts Award 2007. In the Toyota Choreography Awards he was winner of the Audience Award in 2005 and the Choreographer of the Next Generation (grand prize) award in 2008.

Interviewer: Tatsuro Ishii

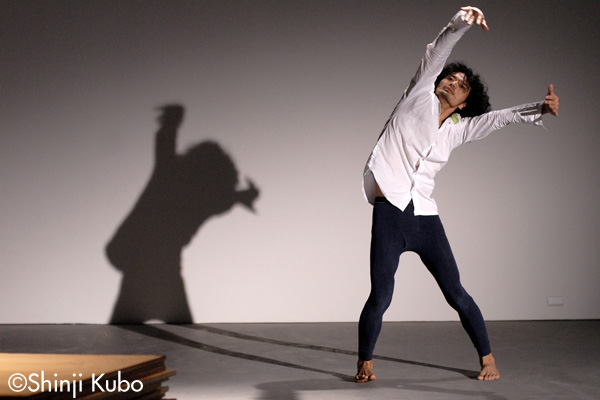

Kotoba no Saki (The Point of Words)

(2008)

©Shinsuke Hatashima

©Yohta Kataoka

©Takayoshi Susaki

©Shinji Kubo

Chinmoku to Hakariaeruhodoni (Confronting Silence)

(2007)

©Ryuichi Maruo

Love vibration

(2007)

Directed by Yukio Suzuki

Music composed and played by Yasutaka Henmi

©Japan Contemporary Dance Network (JCDN)

Inu no Jomyaku ni shitto sezu

(2006)

Related Tags