- The Walker Art Center is considered one of the nation’s “big five” multidisciplinary art centers for modern and contemporary art (*1). Along with its visual arts collections and exhibitions, the Walker’s performing arts programs are internationally renowned. Can we begin by asking you about the history and the vision of the Walker. Did it start as a gallery?

-

Walker Art Center in its earlier days was a gallery, meaning that it represented the collection of T.B. Walker (*2), who was a major figure in the industrialized Twin Cities. He was involved in the lumber business and had his own personal art collection which he was interested in opening up to the public. He was a person quite interested in the arts and traveled the world extensively. He had a very eclectic collection ranging from folk art to very traditional paintings of many different eras to more contemporary works. The first Walker Art Center was in his own home and it was on this same piece of land where the Walker Art Center stands today.

The focus of Walker Art Center as a contemporary art center really did not begin until the 1940s, coming out of our role as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) (*3) project during the Roosevelt administration. The Walker not only started to provide work for artists but also started to connect the art to a much broader general public. WPA really helped to ground the Walker as a place to reach out and connect with everyday people of the Midwest, instead of remaining an elitist institution. I think that some of our outreach and education programs and some of our interests in connecting contemporary art to a broad-based population stem all the way back to this time.

The Walker continued to be primarily a public museum during the 40’s and the 50’s. In the 50s, however, a volunteer committee, called the Center Arts Council (CAC) (*4), was formed, and they began to recommend and even help produce a number of dance recitals, jazz concerts, lectures, and film programs. While they were not adopted as an official part of the curatorial mission, they came under the banner of the Walker, and great artists were invited to perform and important lectures were held. That slowly morphed into more professional presentation of performing arts and film programs.

In the early 1960s, the first coordinator of the CAC, John Ludwig was hired. He was a staff member of the Walker for coordinating events at the Guthrie Theater. Then, a woman by the name of Suzanne Weil took the program and really expanded the programming in the performing arts. It was Martin Friedman who became the director of the Walker in the early 60’s and was really a transformational figure for the Walker that hired Suzanne and encouraged her to have as experimental and exciting a program as she could put together. He was very committed to multiple disciplines and put the Walker on the map internationally. Suzanne was also presenting many of the most famous rock bands at the Guthrie Theater (*5), which was originally seeded in part by the Walker. It was the Walker Board members who brought Tyrone Guthrie over and gave the initial seed money and the land that was owned by the Walker throughout the history of the time with the Guthrie (*6). So, when the Guthrie wasn’t using the theater facility, the Walker could have its own programs happening there.

Through the 60s, rock bands from the Who to Led Zeppelin to Frank Zappa, and a lot of folk singers were presented. At that time, there wasn’t a developed industry of rock and roll promotion, and I think that Martin Friedman and Suzanne Weil felt that in the 1960s, where a lot of the excitement and energy that was happening was in the world of rock’n roll, and I think that they were interested in connecting open-minded willing to experiment generation who was making the 60s music and rock to the threads of exciting innovations happening in visual arts.

In addition to pop music, Sue brought leading figures in Jazz, such as Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, and major new music figures including Philip Glass and the Steve Reich Ensemble. There were also really important residencies by dance artists including Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown, as well as major theatrical innovators like Mabou Mines, Richard Foreman and Robert Wilson. These artists were all making stops here and even getting commissioned by the Walker. That continued throughout the 70’s and 80’s.

It was the year of 1970, however, that is an important point to look at because it was the year that the performing arts became an official department within the Walker. Then, we were really seen not as a subsidiary or ancillary aspect of the Walker, but an official aspect of what the Walker was all about. Until that point, the concerts and recitals were viewed as side-projects to a visual arts center. Now we were really emerging as a multidisciplinary arts center.

The programming through the 70’s and 80’s did not primarily happen at the Walker. There really wasn’t a theater here, so the various curators beginning with Suzanne Weil would find spaces all over town. They’d find co-presenting partners and had often encouraged artists to create site-specific projects all over the Twin Cities. I think that the Walker’s international reputation in the performing arts began to be established with these kinds of commissions and residencies. These artists were recognized internationally, and they’d talk about how the Walker sponsored or commissioned their works. From the 60’s on, there was much openness to innovative international work, but the focus was primarily on American artists. - Did the Walker start performing arts programs to attract more people to contemporary visual arts, which often were seen as difficult to understand?

-

I think that even from the start, it was less of a tactic or a strategy to find new audiences, but rather it came from a view that there were a lot of important artists but they just didn’t happen to be working in the plastic arts. They worked in sound, or they worked in movement but they deserved the same kind of support and platform that sculptors and painters had been given at the Walker. It was of course, wonderful that new audiences were coming to the Walker, but it came out more from an ethic or a belief that contemporary expressions had many forms and it was far beyond just what you can do in the gallery space.

At that period in the 60’s and 70’s in America even major figures such as John Cage or Merce Cunningham or Philip Glass weren’t given theaters to perform in. They didn’t have very many places to play in New York or in other parts of the country. The traditional theaters that were doing long runs were still working maybe with Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey and others, but they hadn’t really opened up to avant-garde at all. So, those artists needed to look at arts centers or gallery spaces. Some of the most interesting work in New York, for instance, was happening in SoHo in gallery spaces or in loft spaces or in warehouses. The Walker served a very critical role as a significant institution to put its name behind these innovators. Some of the events were quite provocative happenings and things that really tested the boundaries of propriety. Giving them the stamp of approval from a major institution helped a number of artists transition into touring their work around the country because then they were viewed as a little more accepted or acceptable.

When we reopened after the expansion in 2005, we did a new catalogue of our permanent collection (*7). It was the first time that we really had a lot of information about the history of the different art forms, including the performing arts in addition to the visual arts. We’re very proud of it because I think that this was a further step toward a sense of equality between the different artistic disciplines and the performing arts programs to become part of the written history of the Walker. - Besides the Walker, were there any other institutions in the U.S. that focused on supporting cutting edge work in performing arts through commissioning and residencies in the 60’s?

- In many ways the U.S. performing arts field’s commitment to ideas such as residencies with artists and commissioning new work was led in part by places like the Walker.

- So, the Walker, acting on its vision, was leading the trend and influenced the field nationally?

- Yes. In fact, the directors of the Walker have gone on to do really interesting important things. For example, Suzanne Weil went on to lead the program at the National Endowment for the Arts, as did Nigel Redden who took her job a few years later. Nigel is now running the Lincoln Center Festival and the Spoleto Festival. John Killacky who had the job before me went on to run the Yerba Buena Center in San Francisco and is now at the San Francisco Foundation. Robert Sterns went on from here to start the Wexner Center and then continued to do good work with Arts Midwest. What I find very encouraging is that for more than a dozen multi-disciplinary contemporary arts centers that started 10 or 15 years after the Walker was established (e.g. MassMoCA, the ICA in Boston, the Museum of Contemporary Arts in Chicago, the Wexner Center, Portland Institute of Contemporary Arts, Diverse Works in Houston), the Walker’s commitment to multi-disciplinary programs across contemporary art forms helped create a template that they could emulate and experiment with.

- Besides the Walker, there are other significant arts organizations in the Twin Cities that are actively contributing to the community and the field and influencing the rest of the country. To name a few, the Guthrie Theater, the Children’s Theater Company, the Playwrights Center, the Opera and the Orchestra. Why in the Twin Cities do so many visionary arts and cultural leaders gather and thrive?

-

People often wonder and ask that question, and I think that we need to point to a couple of things. One is that we have really visionary philanthropists – individuals who are willing to give a lot of money and to help set a direction of very high standards and of adventurousness on the part of the organization. There are individuals and families in this community that date back for a hundred years plus who have funded the arts heavily to make Minneapolis stand out nationally. For example, Ken and Judy Dayton, who were a part of the family who ran the Dayton-Hudson Corporation which evolved into Target (*8), helped establish the new directions for the Walker led by Martin Friedman and gave hundreds of millions of dollars to help this institution and many others.

Then there were major foundations such as the McKnight Foundation, the Jerome Foundation, the General Mills, St. Paul Companies. Inordinate numbers of foundations that support culture were based here in the Twin Cities and I think that really allowed organizations to take interesting chances and encouraged them to collaborate together. This in turn attracted artist to live here. Also, there existed a cultural heritage of the Scandinavian immigrants who really felt a commitment to public institutions and to culture as a publicly funded entity. Perhaps, they became stewards for making culture part of people’s lives. Also, things build on each other. Cultural institutions continue to grow, more people want to live here because they know the Walker is here, the Guthrie is here. Things just keep growing. Last week at the election, something incredibly encouraging step at the State-wide level happened: people voted for tax increase to support culture as well as open land and clean water. - This season started off with Merce Cunningham’s large-scale site-specific work “Ocean,” and it include Batsheva Dance Company from Israel, Chelfitsch Theater Company from Japan, Hoipolloi theatre and a sound artist Ray Lee from the U.K., a French percussion ensemble; Eiko & Koma and the Builders Association from New York as well as local artists programs. The season is consists of 28 different artists’ programs between September 2008 and the end of May 2009. Please talk about the current program policy for the performing arts.

-

We’ve retained the commitment to be involved in both very established artists and emerging artists. Our criteria for established artists is if they are continuing to push out the form that they work in and push themselves in new directions. If artists like Merce Cunningham, who’s about to turn 90, continues to throw ambitious and interesting challenges to himself and his art form, we feel like they should continued to be supported by us. But I’d say that the bulk of our work is with the mid-career artists, people in their mid-30s to late 50s, who are right at the height of their innovative abilities, who aren’t necessarily well known nationally or internationally yet, but who really have a track record of strong work and are asking interesting questions. I’ve always felt, and I believe the directors before me did too, that any arts institution that is an integrated part of its community needs to have and be supportive of in some significant way the artists who are right in their own community. So, we’ve always tried to find different ways to commission or present a work from artist who is based in Minnesota.

About 80% of our program presents artists who are nationally or internationally known. The other 20% we continue to feel is very important and having them both really helps make connections between national and local artists. While we don’t pretend that we can support everyone – there are other organizations that do that more consistently and probably better – we feel that we can create threads that play important roles as part of the ecosystem of the Twin Cities’ cultural scene. - Please talk more in detail about the Walker’s residency programs.

- Residencies tend to break into two different types. One is really about helping artists develop their work. We call them “Production Residencies.” Often artists are faced with the situation to go straight from the rehearsal space to a major theater and premiere a work with a few days of technical load-in. At the Walker, since we opened the McGuire Theater in 2005, we are now able to give the artists enough time to develop and finish making their work.

- How many days do you usually give to the artists to develop and/or finish their works?

- For the artists that we select for Production Residencies anywhere from 10 days to a month depending on the complexity of the work and what the artists’ needs are. Of course when we have an artist in residence there’re all those wonderful opportunities to connect the visiting artists to local artists and local populations, to teach classes, etc. But the primary focus is about giving them a chance to make their work the highest quality that they possibly can so that it can be seen in the best light when it goes to New York or travels internationally.

- Such works after Production Residencies are premiered here at the Walker before going on tours?

-

That’s usually the case, although it is not necessarily the most desirable thing. There’s a certain prestige to do a world premiere, but it also asks your audiences to take a bit more of a chance. Sometimes, works evolves after the premiere. I still think that it’s wonderful for us to have the chance to see the work here first. We’ve probably done 15 or 20 since we re-opened, and most of those works have gone on to travel the world and have been widely well received and well acclaimed.

The other kind of residencies are what we call “Community Residencies”. These are about working with artists either at the earlier stage of their work or with an idea where there is a great interest in being involved with communities who are based here in the Twin Cities. It’s a really involved creative process where artists are combining their work with either issues or passions that exist here locally in the various communities. I think that it’s a way of bringing art and people together in the making or exploration of something that is very enriching for the people. It often serves as artists’ research at an early stage for a work that they want to do further down the road.

We have done these kinds of residencies with Bill T. Jones, Ralph Lemon, Liz Lerman and a visual artist named Nari Ward and many other artists over the years. We don’t try to make it removed at all from the creative work that artists want or need to do, but we try to do it with artists who feel they need or will benefit from and could give back to community members who work within our neighborhoods and communities.

Seikou Sundiata, the poet and performance artist, a few years back had a production residency here for a work called “the 51st (dream) state” which questioned what kind of democracy we have become in America. From an African American poet’s point of view, he explored the whole question of what is it to be an American, what is democracy, etc. We worked in collaboration with the Humphrey Center at the University of Minnesota. There were a series of classes, interactions, workshops, dinner parties and salons where Seikou came and just heard from people and talked to them. He led people through exercises and created some public activities. He videotaped some of the events that ended up in his final art work, which we eventually presented as a finished work the following year. - Do you initiate this kind of project that deeply involves the community?

-

It’s a combination of things. I’d say that the majority happens to be artists who are looking at questions and issues that they are concerned about. If I’m aware that there are the similar concerns or if I think there’s a way to connect very directly with things going on here or with people’s issues and passions that I would take a lead and hope that we will find – and we always have found – communities interested in connecting with national artists and exploring topics. But sometimes, I’d be approached by local organizations or individuals who want to work on a particular issue, and then we will seek out an artist. In any case, it is important that the artist is passionate about exploring the content issue. I don’t want just a community exercise. It’s ultimately about the artwork, but an artwork that can embrace and empower people in its making.

I think that these lines between presentation of art and interaction with art and the collective making of art are all breaking down a bit more. I think that we’re entering into the age where many people are not going to be satisfied with just going and watching art. They will want, in some ways, to be part of it, or to be behind the scenes and knowing how and why it was put together, and so more and more of our projects even that aren’t residencies, many of our commission projects ultimately involve local artists or non-performers, so, more and more of our projects are blurring lines between the local and the global in very interesting ways, and I love that part, but it brings associated challenges financial, logistical, and everything else as well. - Please introduce some of the highlights of this season in the context of local/national interface and the participations of local artists and community.

-

The season’s opening, Cunningham’s “Ocean” that we produced in a granite quarry needed 150 classically trained instrumentalists. We built the stage on the floor of the quarry an hour and a half north of the Twin Cities. Cunningham is a world class artist, but it involved musicians drawn from all over the state of Minnesota playing a John Cage inspired original score. It involved the quarry workers, as well as the people of St. Cloud, and we partnered with the Northrop Auditorium of the University of Minnesota, the College of St. Benedicts and other organizations in the state.

Eiko and Koma were here for a three-week developmental residency. They needed a musician doing a certain kind of Indonesian music. I put them in touch with a Gamelan player via the Shubert Club (*9) in Saint Paul. They were thrilled and ended up having him as a collaborator on the project.

The Builder’s Association, which is another big production residency, interviewed a number of local immigrant community members and integrated that into the visual and aural designs of the work. They also had a website, which we set up at community centers throughout the Twin Cities, where people could record their own stories. These were also integrated into the theater work.

A project by a legendary jazz figure, Yusef Lateef, in collaboration with a local musician, Douglas Ewart who’s nationally known started when Douglas came to me one day and said that his dream is to do a project with Yusef.

“Choreographers’ Evening” has served as the major gathering for the Twin Cities dance community. This is a platform of all local choreographers that’s curated this year by a locally based choreographer, Sally Rousse.

Thus, many of our projects have local / national interface. It shows how much our work has grown. It’s also making some of the most interesting and relevant feelings for audience here. - Do you think that the trend of local/national interface and the audience desire to participate in the process of arts making have to do with the growth in the Internet?

- Definitely, because the Internet is all about the ownership of content and participatory and communicative interaction. I think that it is also affecting the creative process of contemporary forms of live performances, and will affect the more traditional forms in the coming decade or two. But the Walker’s role is to be ahead of the time and try to adopt and embrace these trends. Even if we fail sometimes, we want to continue to function as a kind of R & D engine for the performing arts in the country.

- Do you also conduct community outreach programs in a conventional sense such as workshops and master classes?

-

We have an award winning wonderful education department that has six different departments within, and a number of projects that I just mentioned, like the Builder’s Association having web stations in community centers, were all in collaboration with our education department. They helped us reach out and connect with people. The education program also consistently runs wonderful tours. These are usually through galleries, but some of them are evolving through performing arts now too. It will connect the three program departments and weave the ideas and theme together. For example, the tour guide will talk not just about the art work in the galleries, but the works of the theater maker or the performance artists who will be performing at the theater next month.

There is also a youth education program, which is actively involved with hundreds of schools in our region. Often, it’s a hands-on in arts classes, or it’s tours to the Walker, or it’s combined with our web project, “Arts Connected”, and giving online resources about modern art pieces to children. There are also the public programs out of education department. They sponsor a lot of key speakers, thinkers and writers around art, cultural and other social issues that they bring in on a consistent basis. This includes an important series around the design trends. There’s also just a “communities program” within education that’s really dedicated fully to finding new ways to make connections with other partners outside of the Walker. These are not other arts organizations necessarily but community organizations and collaborative neighborhood organizations who otherwise might not normally find their way to the Walker.

One of the key roles of the education department is interpretation and to help frame for the public the work that we are showing or presenting. They write didactics, create education guides and set up education tours, etc. Historically, most of their work has been for the art works in the galleries but they are increasingly doing similar interpretation for the performing artists. - Have you seen an increase in attendance as a result of community outreach and the relevance of the programs?

-

I think that it’s an interesting dynamic because we’ve retained very consistently over the past 15 or 20 years unusually large audience for a contemporary arts center compared to others around the country. But we also do very challenging work, so, it’s not always easy to get people interested in things that they don’t know about, or don’t know what to call. Our first priority is committed to the mission of supporting artists of innovative forms and challenging work. From this starting point we develop a structure of education, residency and community activities around the work to bring people to it and to support it. We’re always setting a very high bar and major challenges for ourselves because we take on the most difficult work and the most difficult-to-explain artwork. But, that being said, we average 70 to 80% attendance at all of our performances, and many of them sell out.

Our educational programs are very well attended. The education department runs a program called Free Thursdays. Every Thursday evening between 5pm and 9pm the admission to the Walker is gratis and there are special programs, such as lectures, performances and music and gallery tours that attract thousands of people. Many young people are here every Thursday night just to be part of the Walker experience, and that’s been a very successful program. Then, we do special programs like “Rock the Garden” where we bring innovative rock bands to the Sculpture Garden and up to eight thousand people can turn out. A lot of those people then turn into Walker members. So, I think we have effective strategies to continue to have a broad circle of people interested in what we’re doing. - What is the organizational structure of the Walker and how many staff work here?

- The entire Walker full-time staff is about 120 or 125. That includes front of house, people in registrations (the people who care for all the art work), marketing and finance and press. Then there are three separate primary curatorial departments. Visual arts is the largest and the longest standing. There’re as many as five or six curators within that program, either full-time curators or associate or assistant curators. In the Film & Video department there is staff of four and the performing arts have a staff of five.

- What is the budget of the Walker and the performing arts programs?

- The entire walker’s budget is about $22 million, of which the performing arts budget is about $1 million. The performing arts budget only reflects the programming budget, including artists’ fee, travel, lodging, technical and marketing. It doesn’t include all the operations, salaries and other overhead, which is included in the $22 million.

- Do the three curatorial departments coordinate programs to share the same theme or focus?

-

We try very hard and we do as much as we can. I think our current director is very interested in finding even more ways that the different art forms can feel integrated and can be planned together. The challenge, of course, is that there are very different timeframes for each of these disciplines. The Exhibition may be planning four years from now, I’m working hard on finishing plans for the next season which is about a year to year and a half from now and the film department is working on the programs three to six month from now. So, it’s very difficult to line things up, but we’re working on the system to communicate with one another so that we can plan things jointly, or that we can take advantage of when there are things that seem naturally connected to frame them together.

There are times that everyone works together. For instance, last year when the Yoko Ono show came, I was involved in doing some music programming, and there was a slide and lecture program and performance by Yoko, and the film department showed films by her. - The Walker’s current exhibition is featuring Tatsumi Kudo’s work and a film series directed by Nagisa Oshima is going on here too. To date, the Walker has presented major exhibitions related to Japan as well as a number of significant performing artists. Do you think that there’s a kind of “aesthetic match” between the Walker’s programming directions and Japanese artistic expressions?

-

I don’t know quite how to say it intelligently, but I think that the Walker has for decades looked at Japan as another center of innovative thinking and new forms in contemporary art and expression and that were really across disciplines. For example, there was a landmark exhibition that was one of the most popular in our entire history that Martin Friedman led in the mid-80s, called “Tokyo Form and Spirit”. That exhibition drew a great number of people. It covered design, architecture, fashion, visual art, and media and it was a spectacular exhibition.

There’s been a feeling that artists in Japan are often using technology or examining certain questions about living in modern times in ways that feel very ahead of our time. So we try to respond to that by being a major entry point for those artists in North America. Certainly, it’s been the case in the gallery spaces, and in dance, we presented Kazuo Ohno, Sankai Juku, Dairakudakan, Dumb-Type, Kim Itoh, Min Tanaka, Akira Kasai, Eiko & Koma, Kei Takei in the Sculpture Garden, and so on – really a rich long history. The film program has been very internationally-oriented. It’s been committed for a long time to new trends in Japanese films as well as retrospectives of the masters of Japanese filmmaking. - When you consider presenting Japanese artists in the future, what would you look for in them?

- I think that it’s very similar to how we look at American artists or European artists. Is this something that I’d never seen before, or is this something that feels like it’s asking new kinds of questions whether be in form or in content. In recent years, I’m looking at Japanese artists who are really adept at innovation within technology in theatrical work, for example, but who also have an equally powerful questions and contents in what their work’s about. I continued to be very impressed and fascinated with so much work coming out of Japan. And there’s a major figure I really admire but whom I not had a chance to bring over to the Walker and who we’re hoping to work out next year, Saburo Teshigawara. We’re now deeply involved in many grants and other efforts. He’s a kind of interdisciplinary artist who works across many genres, similar to someone like William Forsythe, Meredith Monk, or Merce Cunningham who, I think, is really right for this kind of institution.

- What is the Walker’s vision for the future?

-

I think that we’re interested in moving even further in finding ways that different disciplines work together, finding how these art forms can collaborate or can speak to one another. You’ll see our gallery space starting to feel even more interdisciplinary. We’ve done this before, but probably more frequent collaboration between visual artists and/or filmmakers, performance people and theater artists. We will continue to be a platform that people, who are otherwise kept apart because the fields are kept so separate, can actually come together and be inspired by one another.

I think that you’ll continue to see very much commitment to commissioning work. Even in a down economic time we feel that it’s so important to give artists money upfront to support the making of new work before it’s really seen the light of day yet – what in Europe and I think in Japan is called “co-producing.” I think that as the economic times become more difficult, more arts organizations are pulling away from commissioning work, so we feel that it’s even more important than ever. - You are certainly one of the leaders in the field, serving on grants panels, advisor groups and being an active member of significant networks. I think it connects the Walker’s vision to the field nationally and internationally. Can you briefly talk about the organizations that you or the performing arts department is associated with.

- I’m a co-founder and a part of the contemporary art network, which is 12 organizations all over the country that represent performance programs within multi-disciplinary contemporary institutions. So, that’s an important network. Regarding the National Performance Network (NPN), we’re one of the 12 founding organizations and I continue to be very active with it. There is a new organization called the African Consortium, which is dedicated to the greater exchange between the Continent of Africa and the North America – there are ten organizations involved in that and we’re a founding member. We’re very involved in and I’ve been an advisor to the National Dance Project, which is an important system of support for contemporary dance production and touring. I’ve been on an advisory board for the Japan Society in New York for the last 2 years. Over the years, both myself and Julie Voigt, our Senior Program Officer, sat on The Japan Foundation’s Performing Arts Japan grant panel and we’ve taken regular trips to Japan. I co-chaired with Ella Buff a major meeting around increased commitment in the U.S. presenters field to international programming, called International Presenters Forum at Jacob’s Pillow. I’ve also been on the Etonne Donne, French American Fund for Performing Arts, which is a panel that supports exchange between the French and American artists. I’ve also served as sort of an Ambassador for the Australian Arts Council essentially helping people getting greater awareness and understanding for Australian artists. I’ve also been doing independent special research in Brazil, South Africa and Indonesia around new artists and art forms in terms of launching new projects and collaborations.

- The list of the organizations alone speaks to the fact that the Walker is functioning as a pivot of national and international network in the field of performing arts. Thank you very much for your time today, sharing with us the inspiring history and the vision of the Walker.

Philip Bither

The Minneapolis-based Walker Art Center, an international hub for cutting-edge performing arts

Photo: Kyoko Yoshida

Philip Bither

Senior curator of performing arts of the Walker Art Center

The Walker Art Center, located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, is one of the most distinguished multidisciplinary arts institutions in the United States boasting a long history of activities. The Walker occupies a 17-acre (approx. 6.9 hectare) urban campus that includes museum and theater facilities as well as a sculpture garden. Its programs include modern and contemporary visual arts, performing arts, and film and video, design and new media.

(Interview: Kyoko Yoshida, Director, U.S./Japan Cultural Trade Network, Inc.)

*1

The Walker’s permanent collection includes work from artists such as Matthew Barney, Roy Lichtenstein, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, and Andy Warhol, and its performing arts program has commissioned Merce Cunningham, Ornette Coleman, Wooster Group, Robert Wilson, Bill T. Jones, Meredith Monk, Mabou Mines, Trisha Brown and hundreds of others.

*2

The Walker was founded in 1879 by Thomas Barlow Walker (1840-1928) and was formally established at its current location in 1927 as the first public art gallery in the Upper Midwest.

*3 Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration was the largest New Deal agency, employing millions of people and affecting most every locality in the United States, especially rural and western mountain populations. It was created by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidential order, and funded by Congress on April 8, 1935. Between 1935 and 1943 the WPA provided almost 8 million jobs. The program built many public buildings, projects and roads and operated large arts, drama, media and literacy projects. Almost every community in America has a park, bridge or school constructed by the agency.

*4 Center Arts Council

An advisory group which provided support and advice for the Walker’s programs. The Walker’s staff usually coordinated the CAC meetings.

*5 Guthrie Theater

The Guthrie Theater was founded in the city of Minneapolis, MN, by Sir Tyrone Guthrie in 1963 as the first regional theater with a resident acting company that would perform the classics in rotating repertory with the highest professional standards. After four decades, the original Guthrie closed down and moved to a new location by the Mississippi River to open a new theater complex with three different stages in 2006.

*6

The Guthrie Theater was housed in the same building with the Walker’s gallery and other facilities until it closed down to relocate and re-open in 2006.

*7 catalogue of our permanent collection

Titled “BITS & PIECES PUT TOGETHER TO PRESENT A SEMBLENCE OF A WHOLE,” the catalogue can be purchased at the Walker gift shop or online. The Walker has been publishing catalogues every 8 or so years.

*8 Target

Target Corporation is an American retailing company that was founded in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1902. In 1962, the first Target store opened in Roseville, Minnesota, and in 2000 the company changed its name from Dayton Hudson to Target. It is the fifth largest retailer by sales revenue in the United States, and The company is ranked at number 31 on the Fortune 500 as of 2008.

*9 Shubert Club

The Schubert Club, established in 1882 in Saint. Paul, MN, is a non-profit arts organization that presents concert series annually, operates a Museum of Musical Instruments, and provides various programs to promote classical music.

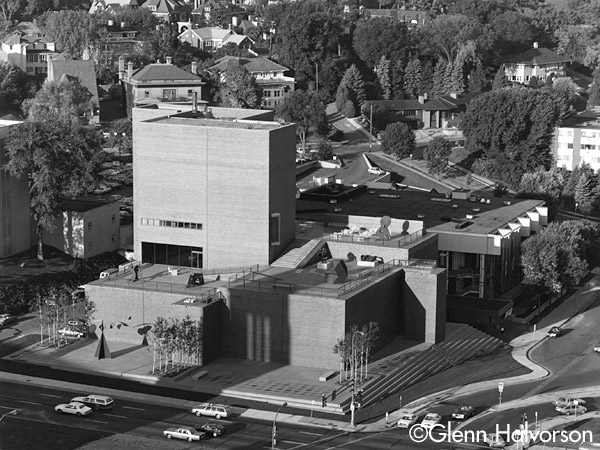

Photo: Gene Pittman

Photo: Gene Pittman

Walker Art Center, 2005. Herzog & de Meuron expansion (Theater Tower) on left and Barnes building (Gallery Tower) on right. February 2005 – a few months before grand opening.

Photo: Gene Pittman

Walker Art Center

https://www.walkerart.org/

Photograph of TB Walker on grand stairway in the foyer of the newly-constructed Walker Art Galleries, 1927.

Walker Art Galleries at 1710 Lyndale Avenue in Minneapolis, 1930 – the “Moorish” facade.

Barnes building in 1985; viewed from east. (The Guthrie Theater is building connected at right of Barnes with the banners extending from roof.)

Photo: Glenn Halvorson

McGuire Theater, 2008.

Photo: Cameron Wittig

Three views of Administrative offices in Herzog & de Meuron expansion, 2006.

Photo: Cameron Wittig

U.S. Bank Orientation Lounge, 2005.

Photo: Cameron Wittig

Bazinet Garden Lobby, 2005. Dan Graham sculpture/video-viewing area.

Photo: Cameron Wittig

Photo: Kyoko Yoshida

Mark di Suvero sculpture, Molecule, in Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, 1998.

Photo: Glenn Halvorson

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen sculpture, Spoonbridge and Cherry, in Minneapolis Sculpture Garden.

Photo: Dan Dennehy

Haegue Yang’s, Blind Room, installed for Brave New Worlds exhibition, 2007.

Photo: Gene Pittman

Gallery view from exhibition, Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love , 2007.

Photo: Gene Pittman

Related Tags