- This July (2013) you have just been appointed artistic director of the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company, haven’t you?

- The Korean National Contemporary Dance Company was launched in August of 2010. As an organization it is still just three years old and the responsibilities carried by the artistic director are great. There is the responsibility of creating systems for it as a national arts organization that are both comprehensive and organic at the same time, and because contemporary dance is still an unfamiliar genre for most Koreans, there is also the responsibility of developing an audience and market for contemporary dance. There is a mountain of work to be done.

- You have been one of the pioneers and leaders of the Korean contemporary dance scene for some 30 years. Would you tell us how chose to make dance your profession?

-

When I was in elementary school I started ballet lessons. At first I was just one of many students dancing in the back row, but they gradually moved me up one row at a time until I was given the chance to dance in the center of the front row. But, during the final performance, everything went white in my head and I couldn’t remember the moves of the dance. I was just a child but it was a big shock for me, and after that no matter how people tried to persuade me, I couldn’t make myself dance again.

After that I went to the Keumlan Middle School, which was affiliated with the Ewha Womans University and on the same campus. At the time, all students were required to take dance classes that involved creating and performing dances, regardless of whether or not they intended to major in dance in the future. That got me involved positively in dance again. Thinking that I wanted to try realizing my dream of dancing once again, I chose dance as my extracurricular club activity in high school. I believe that experience made me discover myself and develop myself through dance, and also helped me learn about finding a place within society. From there I went on to study in the Dance Department of Ewha Womans University. - In the dance department you surely could have studied various types of dance, such as traditional Korean dance or ballet. What made you choose contemporary dance?

- At university, professor Yook Wan-soon taught us the dance technique of America’s modern dance pioneer, Martha Graham. That was “contemporary dance” at the time. It was such a departure from anything I had seen until then and seemed quite unfamiliar, but I also felt a sense of freedom in it. To me, contemporary dance is a form of dance in which you can use technique but your body is not bound to the technique and you are able to express yourself freely. That is what attracted me to it. In fact, when I saw the students at our university who were majoring in contemporary dance and how tall they all were, I had the vague feeling that a short person like me would end up having to choose Korean traditional dance as my major. But, in my second year, my professor advised me to choose contemporary dance.

- I have seen performances of your Ahn Ae-soon Dance Company and found that your works pursue both the contemporary and working elements of traditional Korean dance into contemporary dance.

-

When I was still in university I held “Ahn Ae-soon Dance Recitals” and then, as an extension of that work, I founded my own company in 1985. Looking back, I feel that my personal themes in dance have changed about every ten years. During the 1990s my theme was reinterpretation of the traditional. I was absorbed in the process of interpreting traditional elements in terms of contemporary movement. For that reason, my works of that period can be characterized by a sense of the ritualistic and of a pious and solemn atmosphere. Among the representative works of that period were Karma(1990),

Shikim

(a ritual for cleansing the impurities of the dead before sending them off to paradise) (1992),

Empty Space

(1994) and

The 11th Shadow

(1998).

From the end of the 1990s, my concern for about ten years was finding unique contemporary dance based in things Korean. During that search I had the opportunity to see a Kuk ritual (a rite of song and dance in which a mudan (priestess/medium) offers food and gifts to the gods to ask for a wish to be granted). In the dance of the Kuk ritual I found elements that are shared with the contemporary dance elements of play, dissection/disassembling, improvisation and audience participation, which surprised me. It was a very fresh and inspiring discovery for me. Based on that I began creating dance that incorporated primarily the elements of play and dissection/disassembling. The representative works of these efforts were Gut – Play (2001), A-ii-go (Ambiguous Points) (2002) and Circle – After the Other (2003), and these pieces were praised as constituting a new direction in Ahn Ae-soon’s work.

Now, the thing I have been interested in for the past few years is Korea’s modernization. In the rush of events in the period of modernization, many things were destroyed and many things forgotten, and in their place many new things came in. Korea’s modernization was a collision of tradition and the contemporary that happened in a very short period of time. Out of my desire to put the social and cultural stories hidden within this period, I created the works White Noise (2003), 3 Tenses (2007), Galapagos (2008) and S is P (2012).

I have always chosen subjects of the times from my own perspective and pursued them as contemporary dance. Since ways of thinking and expression continue to change with the times, I believe it is natural for the creators to change too. Perhaps my dance is something that continues to change with the times. - In April of this year you did Soko in Kaite Aru (It is Written There) as a collaboration between Zan Yamashita and your Ahn Ae-soon Dance Company and performed it at Festival Bo:m. You have long been actively involved in exchanges like this between Korean and Japanese dance artists.

- The first thing I performed in Japan was my piece Root. I believe that was in 1983. I was invited to perform for an event commemorating Isadora Duncan. After that, I met the dance producer of the Aoyama Theatre, the late Seiji Takaya when I performed at the Bagnolet Choreographer Competition (current Les Rencontres Choregraphiques Internationales de Seine-Saint-Denis) where he was serving as a member of the jury. Through Mr. Takaya, I was able to participate in the Yokohama Dance Collection (2002), the Dance Triennale Tokyo (2004), the Korea Dance Museum (2005) and other events and perform numerous times in Japan. Mr. Takaya loved Korean dance very much and he invited many Korean dance artists to Japan. He served as a bridge for dance exchange between Japan and Korea and for us he was an irreplaceable international friend. Sadly, he passed away in 2010. Honoring the wishes of his family, a group of dancers gathered to plant a memorial cherry tree in Mr. Takaya’s honor on the grounds of the Daehangno Arts Theater in September of 2012 when I was artistic director of the Hanguk Performing Arts Center. Mr. Takaya loved Daehangno and that tree was planted with the wish that he would always be able to see dance in Daehangno and that he would always be watching us. I hope when people from Japan visit Daehangno they will stop to see the tree. I think a visit will make you feel the depth of the bonds in dance between Japan and Korea.

- Hanguk Performing Arts Center (Hanpac) was established in 2010 as a merging of the Arko Arts Theater and the Daehangno Arts Theater. At the same time, Hanpac took over the organizing of the Seoul Performing Arts Festival (SPAF) and you became the artistic director of both Hanpac and the SPAF festival for three years. At this time the Arko Arts Theater was designated as a dance-centric theater, which I believe had an important impact toward enervating the Korean dance world and expanding the audience for dance. What sort of policies did you bring to your job of artistic director of Hanpac?

-

There was a review of the operation of national agencies and national arts and culture organizations like the Arts Council Korea under the umbrella of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism that led to the opening of Hanpac as a merger of the Arko Arts Theater and Daehangno Arts Theater formerly run by Arts Council Korea. At that time the decision was made that the Arko Arts Theater would specialize primarily in dance along with experimental cross-over works, while the Daehangno Arts Theater would specialize primarily in theater, presenting works familiar to the standard audience.

As the artistic director in dance, I worked to present programs focused on introducing contemporary dance, nurturing young dancers and choreographers and building communication with the audience. It had been 50 years since American “contemporary dance” had entered Korea. During that time a contemporary dance world had been formed primarily in the universities and had produced many dancers and choreographers, but the works they produced were still stuck in the modern dance era. But, at the time of these new developments (in 2010), the Korean dance world was in a period of change that involved looking at what was happening in the international dance world and asking what Korea’s own contemporary dance should be in order to move from modern to contemporary dance. In response to this, there was a need to provide a rich variety of new experiences through creation, education and festivals. There was also the need to deal with the issue building audience in a situation where most people saw contemporary dance as “difficult” and “hard to understand” or “unfamiliar.”

To answer these needs, we started a number of programs aimed at finding and nurturing new dancers and choreographers, like our “Soloist” program that selects and brings together emerging dancers and choreographers from Korea and abroad in the genre of contemporary dance, ballet and traditional Korean dance to create works and give performances, and our “Rising Star” program bringing together next-generation choreographers. We also tried planning collaborative works that brought together artists from other dance genres like hip hop and media performance to overturn people’s preconceptions of contemporary dance. In the area of efforts to develop audience, we made efforts to bring in new audience from outside the dance world with initiatives like gathering a panels of artists and critics from other genres like film or fine arts and organizing groups of general audience and creating venues where they could meet with the dancers and choreographers and talk with them directly about works and dance in general. Through experiences like these that give people the opportunity to look at what they had considered “too abstract” contemporary dance from a number of new perspectives, we are now finding more young people from the general audience enjoying dance, while a group of hard-core dance fans is also being formed. - In the same year as Hanpac, the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company was also newly created. What were the events leading up to this development?

-

Under our country’s previous administration’s social reform program there was a major review of the culture and arts field. Former President Lee Myung-bak proposed a culture and arts program as part of his campaign platform that consisted of four main pillars, one of which was “Creating a country of strength in cultural creativity”. One of the specific initiatives in that program was “establishing culture and arts institutions, strengthening their operations and nurturing national arts organizations.” In line with this campaign promise, the Arts Council Korea was relocated and the Artist House facilities developed, the National Theater Company of Korea was incorporated as non-profit organization, and The Korea National Archives of the Arts, the Hanguk Performing Arts Center and the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company were newly established.

Establishing a Korean National Contemporary Dance Company was long-time dream of the dance community and numerous proposals for it had been raised in the past but failed to reach fruition. In theater there was the National Theater Company of Korea and in dance there was the Korea National Ballet and for traditional Korean dance the National Dance Company of Korea, but in the case of contemporary dance, we felt that everything from creation of works to education had been left up to the efforts of the private sector. In times like these, there is definitely a limit to what can be done when the private sector has to bear the full weight of the system for creative work and production. Policy based on a good balance of support makes it possible to bring people a wide range of performances to view, and meeting with the audience through these performances contributes to the further development and vitalization of contemporary dance.

I believe that the government has now begun to support contemporary dance with the awareness that they are supporting contemporary creativity just as in the other genre that seek contemporary relevance. In the contemporary are reflections of our lives and all of the aspects of our cultural activities. Without knowledge of these things, we can’t know how people are living in the 21st century. - What are the policies guiding the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company?

-

Our slogan is “Contemporary Dance as Art toward the People.” And in order to realize this aim, we base our programs on the main pillars of “Creation of high-level contemporary dance works,” “Improvement of dancers’ skill by operating project members,” “Invitation performance of excellent choreographers in Korea and abroad” and “Active overseas exchanges.” The previous artistic director, Hong Sung-Yop undertook a variety of initiatives, but moving forward, I believe the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company needs to build its own solid system of operation.

A particularly pressing issue we face is the barrier that exists between ourselves and the audience. If you ask 100 Koreans today, 100 would probably say that contemporary dance is too difficult, too abstract and something that they don’t really understand. Contemporary dance should be an art form that is alive and developing with the populace in the present, but in fact there is a distance separating the art and the people. The big issues that the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company faces now are how to meet the public while maintaining artistic substance and an experimental approach, how to expand the points of contact with the public while strengthening the contemporary relevance of contemporary dance and how to pursue both artistic worth and public appeal at the same time. The direction I want to see us pursue is contemporary dance as a shared public asset that anyone can participate in and enjoy, regardless of social strata, region and generation; to find in dance the common social and regional elements of life together with the audience and to create together dance that embodies it. - Would you tell us about some of the specific programs you are engaging in?

-

Each year we plan to create and perform four to six regularly scheduled productions. In September we will present the first of these regular productions since I became artistic director. It is titled

Eleven Minutes

and it will be performed at the Seoul Arts Center Jayu Theater. This is a work that was planned and initiated by the previous artistic director and it involves five young dancers taking inspiration from a text by the Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho’s book

Eleven Minutes

to create expressions of soul and body, and love and life. Also, in order to show that contemporary dance is not an art that uses dance as its sole expressive medium, I believe that there is a need to bring in a mix of other genres as well. For that reason, in this work we brought in the young jazz band K-jazz Tno and had the poet and playwright Kim Gyoung-Ju participate in the project as dramaturge. Before the public performance we gathered a group of six professionals, including a dance anthropologist, dancers and critics, and we did a showcase presentation. In ways like this we are creating platforms for thinking about contemporary-ness in the arts with professionals from various genres with the aim of searching for ways to make contemporary dance an art for the general public with a style that is distinctive and unique to the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company. From now on, I want to see us bring in professionals from other genres and create works that will remain as part of our repertoire for a long time.

I plan to present a work that I have planned and developed this December, and I am considering making it a heart-warming work on the subject of family. Until now, contemporary dance has been an art form conducted in small studios with a young and experimental orientation in pursuit of artistic expression. I believe that is part of the reason for the distance that has been crated between it and the audience. I hope to see works of contemporary dance that will be enjoyable for the whole family to view, much like the ballet works Swan Lake or The Nutcracker Suite.

In order to create a program that is organic in nature and based mainly on regularly scheduled performances, we will need to create a repertoire of works for the regular performances. Creating a repertoire will enable a shift from performances of one off productions to a performance repertoire that can be distributed, in order to make regional tours and long-run performances possible. I also want to conduct workshops along with performances in order to give people experiences of the self and the body that lead to discoveries of the instincts and everyday phenomenon that lie within and, in turn, lead to deeper understanding of dance. I also want us to listen to the stories of people living in the different regions and create works of dance that give expression to those stories.

Another thing I want to do, which we have already tried at Hanguk Performing Arts Center, is audience-participation type works. Something we have already started with our September presentation of Eleven Minutes is open studio sessions and showcases as platforms for audience monitoring. Having people of the general public come in an watch studio rehearsals and then exchange opinions with the artists, creates a positive kind of tension for the artists and provides the audience with a point of approach to deepen their understanding of dance. Watching contemporary dance provides an opportunity to think together about contemporary society’s issues and historical issues. I believe that in order to express through dance everything from the historic elements influencing our times to the daily realities of our personal lives, we need a process through which we can come to understand our times together with other people.

Creating programs of long-run performances and the related business operations for our Korean National Contemporary Dance Company will create conditions where the dancers and choreographers will have a stable economic base from which to concentrate on their creating activities. At the company, we have adopted a “project-based member system” in which the participants work on a contract basis for each specific project, rather than a full-time company member system. The usual length of these project contracts is three to four months, but I believe that longer-term contracts of about 11 months are also a possibility.

In addition to these programs, we are also planning a dance-related publication program that will involve people from the academic world in areas like art and philosophy, and also educational programs aimed at specialized professionals. I believe that our Korean National Contemporary Dance Company has the responsibility to involve in community dance in a broad sense of the term. - “Invitation performance of excellent choreographers in Korea and abroad” and “Active overseas exchanges” are two of the pillars of the company’s policy you mentioned earlier. Would you tell us your ideas on the subject of international exchange?

-

During the three years that I served as artistic director at Hanpac, we invited the French choreographer Joelle Bouvier and produced the work

What About Love

with him, and we did a co-production of Social Skin with Ivgi & Greben, who are considered important choreographers of the next generation in Europe. We also held performances at New York’s Next Wave Festival and in Mexico and Germany.

Korea’s domestic market for dance is small and it will require a good amount of time to develop the routes for distribution of dance works. I want to work actively to promote international exchange with countries overseas that have large dance markets and audiences. Of course, I am also thinking about co-production of works. However, to engage in collaborative production of works requires that we have a vision; we need to have a philosophy that is relevant for Korea in this era and the methodology to give expression to it. We also need people who are able to work on equal terms with foreign creators. To be honest, since I have only been here at the company for about a month, we haven’t been able to gather these resources and personnel yet. Now, we need to apply ourselves to a serious study of what directions the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company should pursue with regard to overseas exchanges. - I would like to ask you next about your views on the current state of Korean contemporary dance. You have said that despite its short history, Korean contemporary dance has made big progress and that Korean dancers have gone to America and Europe and won recognition as dancers. You have also said that Korean creative dance is becoming globalized and its choreographers have also been recognized internationally. Would you tell us what you see as the reasons for this progress?

-

I think the role of the universities has been an important one. In the Republic of Korea, I believe that there are 40 to 50 universities that have dance departments. These departments have produced many accomplished graduates. However, while this educational system teaches technique and dance skills, it is difficult to say whether this system is producing true creators. In fact, there are many young people coming out of the system with good physical attributes and technique, but we see very few who can be called choreographers. I think that the nurturing of choreographers will be one of the keys to the development of [Korean] contemporary dance in the future.

While I was at Hanguk Performing Arts Center, we started a two-year “Next-generation Choreographer Class” in 2011 as an ARCO performing arts incubation program. This course is taught with a curriculum aimed at teaching the participants to think for themselves, create theories, make presentations that describe abstracts for dance in words and instills the ability to express oneself in physical movement. It includes an 8-month education program based on mentoring and provides opportunities for exchange with domestic and foreign artists and showcase performances, and in its two years 22 persons participated. We hope that programs like this will help produce choreographers to lead the next generation. - Would you tell us your views on the recent trends in Korean contemporary dance? Are there any choreographers that you are watching in particular?

-

Until now, I have felt that there has been a lack of diversity in the works created, but recently we are seeing works showing great diversity in expression. Diversity in this sense is a matter of the consciousness an artist brings to his or her approach to dance. In other words, I believe that we are now seeing greater diversity in the viewpoints from which artists are perceiving our times through dance.

Among the artists now, I am particularly watching the work of Im Jee-Aee, who majored in Korean dance and is now active in Berlin, exploring the possibilities of new dance vocabulary emerging from the meeting of tradition and the contemporary, and the body and media. Other artists to watch are Youn Pu-Leum, who creates works dealing with directions related to feminism, Park Sun-Ho of the Brecht Dance Company, Shin Chang-Ho of the LDP Dance Company, Kim Sung-Yong, who has performed frequently in Japan, Kim Jae-Duk of Modern Table, Kim Bo-Ram of the Ambiguous Dance Company and Ji Kyung-Min of Goblin Part. I am looking forward to seeing in what directions these choreographers will lead the Korean contemporary dance world from now on. - Recently there has been an increase in the number of producers and production companies specializing in dance.

-

The Korean dance market is so small and the base so lacking that people who are put in charge of production don’t continue for long, due to factors like the economic realities. For that reason, the leader of a dance company usually served as its producer as well. In the past, for people who had majored in dance through high school and university, they had no other choices than to become a dancer or choreographer, but now some of these people are beginning to choose to work in stage production or as producers. So, now there are younger people in their 30s or early 40s active in these fields. Hoping to increase the number of qualified people in these fields, we created a “Dance Production Professional Training Program” in cooperation with the Korea Arts Management Service when I was at Hanguk Performing Arts Center. Tying up with the Next-generation Choreographer Class, this was a program to match choreographers with young production person and have them put together a production plan. Because even if you nurture good choreographers, if you don’t have producers to distribute their works the market will not grow.

One recent trend is the decrease in the number of dancers who are keeping a position as company members and a shift toward a project-specific system in which the company name may be used but there is a new team selected for each project going to performance. Personally, I just dissolved my own company recently. This is because of the fact that there are restrictions on the activities that a representative of a national company can engage in as the representative of a private company, but also because there are fewer dancers in positions as full-time company members and more working on teams put together for individual productions. I think many companies are operating like this now. I believe it is also a result of the fact there is a greater demand for producers and production professionals.

Also, with dance festivals like the International Modern Dance Festival (MoDaFe) and the Seoul Int’l Dance Festival (SIDance) and comprehensive performing arts festivals and events like the Seoul Performing Arts Festival, Festival Bo:m and Culture Seoul Station 284, there are now more platforms for dance performances in Korea than in the past. So, there is also a need for more producers and production professionals to supporting these events. I think that these conditions will naturally lead to new developments in contemporary dance. - In closing, I would like to ask for your thoughts about the societal role of contemporary dance.

- I believe that being contemporary means to understand society, to have awareness of the world and history, to think about contemporary issues and project ideas. It is the same with dance. I want it to be a medium that uses the body to be aware of, experience and help heal the problems of contemporary society, and I believe that the role of contemporary dance should be to discover a variety of physical contexts, like the historical body, the social body, the body at play and then create and present dance works that connect them to contemporary issues. Unfortunately, Korean contemporary dance is still concerned primarily with personal or individual aesthetics. I hope to see an increase in the number of contemporary dancers and contemporary choreographers who go beyond that to create contemporary works, and I want to see the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company become an entity that does that too.

Ahn Ae-Soon

Korean contemporary dance,

Progressing dynamically under new national arts policies

Ahn Ae-Soon

Born in 1960, Ahn graduated from the Dance Department of Ewha Womans University and then received a Doctor of Science degree from Hanyang University.

In 1985, she formed the Ahn Ae-soon Dance Company. Invitations to perform at international festivals include the Yokohama Dance Collection, Festival Global Dance, Singapore Arts Festival, Festival Internacional Cervantino, Dance Triennale Tokyo, Korean Dance Museum and others. Her unique creative style that seeks to express traditional Korean culture and philosophy as well as Korean dance movement through contemporary dance has won the attention of critics. Her awards include the choreography award of the 1998 Bagnolet Choreographer Competition, the 2000 Korean Dance Critics Award, the 2003 best choreographer award The Modern Dance Promotion of Korea and the 2004 Arts Council Korea artist of the year award.

For her activities in musicals, Ahn is also the recipient of the choreography award of the Korean Musical Awards in 1997 and 2006 and the choreography award of the 2007 Musical Awards. From 1985 to 2013 she was artistic director of the Ahn Ae-soon Dance Company, from 2010 to 2012 she served as artistic director of the Hanguk Performing Arts Center and the Seoul Performing Arts Festival. As of July 2013 Ahn is artistic director of the Korean National Contemporary Dance Company.

Interviewer: Noriko Kimura, Seoul-based performing arts coordinator, translator

Korea National Contemporary Dance Company

CompanySeoul Calligraphy Art Museum 3fl, Seoul Arts Center Nambu Loop Line 2406, Seocho-gu, Seoul, Korea 137-718

Phone. +82-2-3472-1420

https://www.kncdc.kr/

Ahn Ae-soon Dance Company

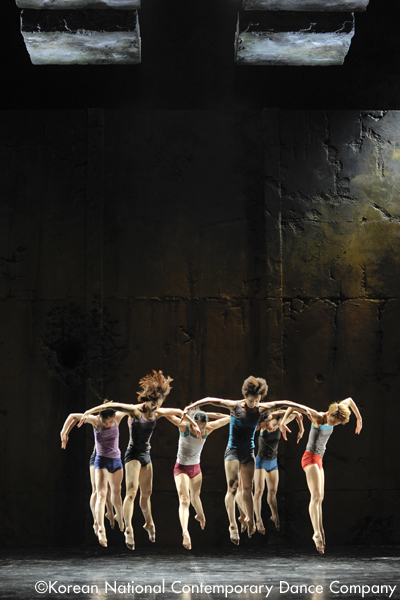

Circle – After the Other

(premiered 2003)

Ahn Ae-soon Dance Company

White Noise

(premiered 2007)

Ahn Ae-soon Dance Company

Bul-ssang

(premiered 2009)

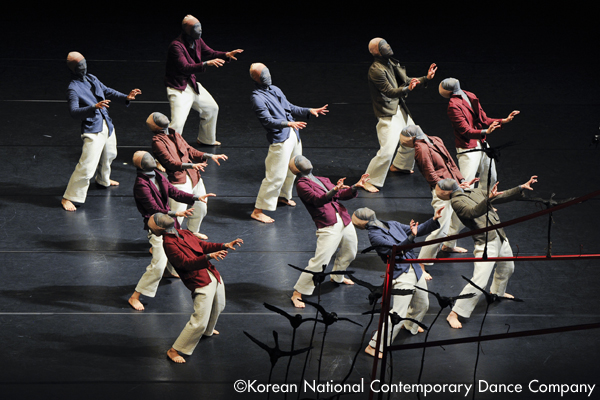

Korean National Contemporary Dance Company

Suspicious Paradise

(2011)

Korean National Contemporary Dance Company

HOSITAMTAM

(2012)

Korean National Contemporary Dance Company

Eleven Minutes

(2013)

Related Tags