- For the international audience you are certainly one of the best known Korean directors thanks to a number of prominent productions such as the joint production by your Michoo company and Japan’s Gekidan Subaru (Theater Company Subaru) of the play Hibakari—400 Years of Portrait (2001), the production you directed at Tokyo’s New National Theater of Ariel Dorfman’s play The Other Side (2004) and as the overall director for the opening ceremony performances of the joint Korea-Japan holding of the FIFA World Cup in 2002. Could we begin by asking you to tell us about the history of your involvement in theater?

- After graduating from high school some friends and I rented a small practice studio of about 66 sq. m. on an island in the Hangang River, and the production of M.J. Synge’s In the shadow of the Glen that we mounted there was the start of my career in theater. After that I joined the theater company Sanha, where I worked as a directing assistant to Cha Bum-seok, who is recognized as the prominent figure in Korea’s realist theater movement, and others. At the same time I attended Sorabol College and began a formal education in theater arts. The year after I graduated from college, my teacher, Ho kyu started the theater company Minye, and I became one of the founding members, and one of the new company’s early productions, a play titled Seoul Maltugi , became my debut work as a director. This work was later performed at the 1984 Korea-Japan Theater Festival in Tokyo as well.

- Seoul Maltugi is a Madang [folk] theater (*) play that includes criticism of authority and it, along with the Madang-Nori performances you have presented annually for the past 30 years, is one of the many works using forms of expression based on traditional Korean theater that you have presented over the years. Were you interested in traditional Korean theater from the very beginning of your career?

- I began gathering materials on traditional Korean theater when I was a student. Also, my teacher, Ho kyu, is an important figure in the history of Korean theater as the first to attempt transplanting traditional forms into contemporary theater. Due perhaps to that influence, when I went to England to study the Royal Shakespeare Company’s system I got the very strong feeling that I wanted to develop a theater language of my own. Korea has old traditional performance arts including mask theater and ritual plays called Ku and Namsadang consisting of a variety of performing arts performed by traveling troupes of musicians and dancers. So, I also began to explore the traditional arts and aesthetics and search for my own unique ways to apply them in the contemporary context.

- When you made your directing debut in the mid-1980s we are told that there were many experiments with making contemporary use of the traditional Korean performing arts in what seemed to be a paradigm shift away from realist theater based on scripts and spoken lines and toward forms that incorporated the physical aspects of traditional Korean theater and an emerging small-theater scene.

- I felt an aversion to artificial intonations and hairpieces or wigs used in theater in translation at the time and I resisted doing plays in translation, but I never had any particular desire to start a small-theater type movement. Inherently, I believe that theater is a composite art form that brings together the actors’ acting, music and art into one unified performance. In 1986 I got together actors from my generation to form the Michoo theater company, and at the same time we started an actor’s school and formed an orchestra with the aim of creating a performance style that brought together the spoken storyline, physical movement and song in a unified performance. In other words, our aim with Michoo was to create a company that could do both acting and music performance.

- After your activities with Michoo you eventually became the first artistic director of the reorganized National Theater Company of Korea, Inc. Could you tell us how you felt after taking over that new position?

- To tell the truth, taking on the job of artistic director wasn’t easy for me. I felt the pressure of the important job of having to build a new type of national theater company, and I also had the feeling that perhaps the job of changing the national theater company was something that should be left to the leadership of younger talent. But, I decided to take the job because I felt that establishing a positive new direction for the national theater company would be good for Korean theater as a whole.

- Why was the National Theater Company of Korea made into an independent organization?

- After its establishment just prior to the Korean War, the National Theater Company of Korea led the theater world in Korea for many years, but there were factors like a failure to present theater that was relevant to the audience in the 1980s and an overall lack of impressive accomplishments in the last 30 years. Some of Korea’s representative directors tried their hand at the job of artistic director during this time, but under the bureaucratized system it ended up as nothing more than repetitions of the kinds of works they had been doing in the private sector being presented in a public institution. You could say it was a problem of a lack of imagination and autonomy. Many people in the Korean theater world felt the seriousness of this problem and there was a general desire for someone to reform the system and reposition the National Theater Company of Korea. This desire in the theater world was behind the eventual move of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism to change the status of the National Theater Company of Korea from that of a resident company of the National Theater to an independent incorporated organization.

Prior to this in the year 2000, the Korea National Opera Company, the Korea National Ballet Company and the National Chorus Company of Korea became incorporated organizations when they were shifted from the National Theater of Korea to the Seoul Arts Center. So the issue and this trend toward incorporating these national arts and culture organizations has been around since that time. And the current [Lee] administration had clearly stated its policy of incorporating the National Theater Company of Korea and the National Museum of Contemporary Art as independent non-profit organizations early on.

In 2009 a white paper was issued for the plan to incorporate the National Theater Company of Korea and an act was implemented to set aside a budget of 4.7 billion won (approx. USD 4.35 mil.) for the incorporation. Then in April of 2010 the contracts of all the former National Theater Company of Korea members terminated and in June a new board of directors was put together and in July the new National Theater Company of Korea, Inc, was launched. Then, I was appointed for the post of the company’s first artistic director in November of 2010. But the path toward this incorporation was not always a smooth one. There was the contract termination of the former company members, conflicts with the labor union that led to strikes and cancelled performances and there was disagreement over the choice of artistic directors. However, from a state where the art of theater itself was in danger, we were able to find ground for the new National Theater Company of Korea to move forward boldly, and in January of this year we opened our new company’s maiden production of Oedipus Rex (directed by Han Tae-suk) at the Myeongdong Theater. As for the National Museum of Contemporary Art, its incorporation is now being reviewed in a congressional screening committee. - Would you tell us about the organizational structure of the National Theater Company of Korea?

- There is a board of directors that reviews and makes decisions on issues concerning the company’s major directions. Then there is the artistic director and the resident directors and the administrative director. The term of the artistic director is three years. The three resident directors have a term of one year. The artistic director and the resident directors are responsible for the specific programming while the Program Planning Dept. handles the practical aspects. Then there is our Academic and Publishing Dept. and the Accounting Dept. Besides these departments there is a separate National Children and Youth Theater Research Institute under the company’s auspices.

- What is the composition of the Company members?

- There are only two [permanent] company members and they are Chang Min-ho (87) and Paik Sung-hee (86), who have served as senior members of the National Theater Company of Korea since its founding (in 1950). In the past, the National Theater Company of Korea had on its payroll receiving a regular salary like national civil servants. There is of course nothing wrong with receiving a salary as such, but if financial security causes laxity in theater people and causes them to choose the safest course in the things they do, that is a system that has to be reformed. Theater people should live through theater, and if their lives become a matter of just going to work at their jobs every day, there will be no progress or development. It is important for artists to make a living, but I believe that the fundamental part of our job is to show that there is something more important than that.

After assuming the job of artistic director, I stated that we would create a repertory system for our company’s works. Then I started a system where auditions would be held to select company members for each season and they would be given one-year contracts. The aim of this system is to create a balance between economic stability and creative development. The desire is to give a larger number of theater people the opportunity to be rewarded for their work, rather than having the same small group of people receive all the rewards and support available. Art has to always be alive and flowing. And it always has to be responding to the changes in society. I believe that when financial security becomes a lure that weakens the thespian’s societal awareness, it is no more than a regressive system. - What does the repertory system for the company’s works you just mentioned involve?

- I want to create a system that creates works that can be loved by the audience of a span of several years rather than short-lived works that end after one performance run. To create good works you need good actors. I want to make it one of my missions is to create such a system.

- What is the role of the Academic and Publishing Department?

- In addition to creating works, the National Theater Company of Korea is also devoting efforts to educational programs. Running these educational programs is one of the main jobs of the Academic and Publishing Department. Many universities in the country have theater arts and film departments, but under the system as it is today, it is difficult to train and nurture professional actors. At the National Theater Company of Korea, we intend to develop programs capable of turning out professional theater people. Currently, we have launched practical educational curriculums including an actor training program, director and playwright workshops and masters classes inviting foreign theater professionals as instructors. We also have what we call an “audience classroom” where we have open script readings and preview performances that audience can come and watch and then discuss with the director and actors.

However, prior to these kinds of practical educational activities, I feel a need for social education. Because theater people need to understand society and human beings. Acting must be based on things that the actors want to communicate or strong feelings that they have. They have to know how society is structured, what contradictions it carries and what a variety of different people there are. Isn’t it only after you understand these things that you can create works of meaning and relevance? I want to begin by taking them to places like the slums and the courtroom where they can discover the different faces of society.

Other jobs of this department include publishing “rehearsal books” recording the development of the National Theater Company of Korea’s productions from the rehearsals through the final performances, publishing a quarterly magazine, printing the programs for performances and keeping an archive of videos of the performances. - You have established a National Child and Youth Theater Research Institute under the company’s auspices. What kind programs and activities does it pursue?

- We established it in hopes that the young people of the next generation will be able to learn about people and the world in an open way and that theater will help give them the strength to be able to look at life seriously. This office was just opened his May but going forward plans call for it to be involved in creating quality child and youth theater works and establishing a system for such creation, as well as working to train and nurture human resources and specialists in this area, while also working to grow the audience and organize nationwide tours of productions to include regions that are often excluded from arts an culture programs. We hope it will become a model for child and youth theater companies.

- So, you have started a broad range of programs for creating works, education and child and youth theater. Can you tell us something about the concepts that define the direction of the new National Theater Company of Korea’s activities?

- Our approach to the activities of the National Theater Company of Korea is expressed most clearly in our “Declaration of National Theater Company of Korea.” It may be a little long, but let me quote it here.

The theater we pursue will express the true humanity and the truth of life that is here and now. The theater we pursue will renounce any pretense of exaggeration and rehabilitate the quintessential life force of the theater. The theater we pursue will embrace living heritage of Korean theater and expand the horizon of contemporary theater. The theater we pursue will answer the questions of today’s Korean society and suggest radical agendas through the artistic practice. The theater we pursue will transcend the boundary of theater and be a window of communication and culture exchange with the world.

This declaration is written on one of the walls in our facility. The 60-year tradition and history of the old National Theater Company of Korea spanned the same 60 years as the history of modern Korea after the Korean War. Building on that tradition, we want to be a company that can bring to life the inherent potential of theater as a total art form that brings together poetry, music, dance, space and time, media and more. To do that, I believe it is important that the larger potential audience that exists in society and bring them to the theater. At the same time, since we are a national institution, we need to develop a vision from both a national and international perspective. - Could you explain in more specific terms what you mean by a vision based on both a national and international perspective?

- Regarding the national perspective, we have to create a theatrical vision that looks to the future with a focus on improving relations between North and South Korea and ultimately our reunification. For example, after our liberation [from Japanese colonial rule] at the end World War II many of Korea’s theater people went to People’s Democratic Republic of Korea in the North. And after the separation into North and South Korea there has never been any exchange between the theater people of the North and South. This is one of the problems that has to be taken into account in the National Theater Company of Korea’s long-term vision, I believe.

Regarding the international perspective, some explanation is necessary perhaps. The “National” in the National Theater Company of Korea’s name has a strong nuance of nation. A nation is a nation as it is distinct from other nations. So, the national theater company of the Republic of Korea should be conscious of the national theaters of other countries and establish relationships with them, I believe. One of the significant events of the past was how Jean Vilar revitalized theater from the grassroots level through his activities at France’s Théâtre National Populaire and other platforms, but I believe that today there is a need to bring new vitality to theater through exchanges with other countries. At the National Theater Company of Korea we are interested the possibilities that the process of dramatic change in northeastern Asia can bring to theater development and we are now working to promote theatrical collaboration and exchange between China, Japan and Korea. This should lead to mutual understanding and cooperation through theater. These three northeast Asian countries have a lot of similarities and using the overall processes of theater to bring out common areas of interest and expand mutual understanding between the three is one of the visions of the National Theater Company of Korea. - As a theater company you will be pursuing the vision you have described through the theater works you present. May I ask what your personal idea of a good theater work is?

- Different directors have different standards regarding theater works, but for me the most important thing is social relevance. I believe that theater is one of the tools that can be used to send out messages and communication with the society. I want to create not only works that show the audience things from the stage but also works that allows us to feel the changes I the audience from the stage. A good work is one that uses the stage to share feelings and communicate with the audience.

- You just said that theater is a tool for sending out messages and communicating with society, but is the National Theater Company of Korea able to send messages that are critical of the government?

- Even though we are a national theater, there is no idea that we should be presenting works that suit the tastes of the government. However, theater is not a tool for inciting conflict. It also can be a means to solve conflicts. Good theater can serve as an antidote for society’s ills.

- From what you say, your company will be involved in a wide range of programs and activities. Could you tell us what your budget is like?

- Although we are an independent incorporated organization, we operate under a system by which we receive government funding on an annual basis. In 2011 that annual budget was approximately 5.2 billion won (approx. USD 4.35 mil.), and when you subtract personnel salaries and operating costs, we have about 2.5 billion won (approx. USD 2.3 mil.) for funding our programs. Since this is our first year of operations, we won’t know exactly until the accounting is done at the end of the fiscal year, but we believe that about 45% of our budget goes for our productions and related business.

- Would you tell us about your company’s facility that opened this March?

- The new base of the National Theater Company of Korea is a complex behind Seoul Station now called the “Open Arts Space.” The complex was originally built in 1981 as a logistics base for the Defense Security Command involved with the gathering of intelligence and research and the facility consisted of vehicle garages and maintenance/repair workshops that were used for 30 years before the site was vacated and its operations moved to another location. In 2008, Ministry of National Defense gave the approval for the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Sports to used the vacated facilities for an arts and culture space.

There are two theaters in the complex. One is a 323-seat theater named the Paik Sung-hee/Chang Min-ho Theater after the two senior company members Chang Min-ho and Paik Sung-hee, and it is used for the performances of the company’s main selected works. The other is the 100-seat “Theater Pan” which is used not only for plays but also as a venue where artists from various genres including dance, art, music, film, performance and design can come together to meet and explore the possibilities of collaboration and experimental works. We also have a working relationship with the Myeongdong Theater for presenting works there. In addition, our complex has two studio spaces that are used for rehearsals and for our educational programs. These facilities were all created by renovating the former garage and workshop facilities, and they have become quite interesting spaces. In addition to being used as creative spaces, we hope they will become cultural spaces for the citizens as well. The office wing is shared with the Traditional Arts Department of the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Sports. It is very significant and beneficial that the newly re-launched National Theater Company of Korea has been blessed with facilities like these. - The red exterior of the complex is very impressive. It there some special meaning to this red coloring?

- It is intended to express the spirit of challenge and passion. In Korea the color red has long been strongly associated with communism and there were worries at first about whether the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Sports would agree to painting red exterior and whether the general public would accept it. But, fortunately, after Korea’s joint hosting of the football World Cup [in 2002 when all the South Korean supporters wore the red of their team’s uniform] the “red complex” no longer exists and the red exterior of our facility has been well received.

- What significance has the incorporation of the National Theater Company of Korea had in Korea’s performing arts world?

- The incorporation of the National Theater Company of Korea has first of all given us the need to deal with the issue of deciding our own future and the reason for our existence. That is why need to build a strong foundation by establishing a repertory system and creating works that will bring a large audience to our performances. In addition to building this foundation to make us a viable institution, we have to create works that have the power to move people like in past eras when theater was a influential force in society. Since our maiden production of

Oedipus Rex

we have continued to present works with strong cultural and social vision in our new theater’s inaugural production of

March Snow

(written by Pe San-shik, directed by Sohn Jin-chaek) and our regular-schedule production of

Kitchen

(by Arnold Wesker, directed by Lee Byun-fun) that have brought to us a large audience. In this way, we will continue to create the viability, the

raison d’être

of the National Theater Company of Korea.

As a national institution, the National Theater Company of Korea also has the role of supporting the creative flow in the private sector and helping in the creation of new movements in the theater world. Because we believe in the vitality of the young generation of theater people and the metabolism of the next generations, we have worked to create an environment where they can create freely. One of the products of these efforts is Theater Pan, and we hope it will become a “power station” for the performing arts where artists from other genres can work together with theater people to create new works. - How do you view the positioning and role of the National Theater Company of Korea in your country’s theater world?

- There is still a feeling among many theater people in Korea today that if the National Theater Company of Korea is healthy and vital the Korean theater world as a whole becomes healthy and vital. The National Theater Company of Korea can be the one to pose questions about the contemporary directions of theater and stimulate responses that lead to new movements. Of course, it is able to play this role because it is a public institution that receives a given budget to operate with. The atmosphere in today’s Korean theater world is one where people expect us to perform a role theatrical exploration and pursuing new directions because of our foundation as a publicly funded institution.

We want to create works base on universal dramas of humanity and the world brought to the stage in an atmosphere where theater people are able to think and work freely with as few corrupting pressures as possible. I want the National Theater Company of Korea to be a group that continues to pose questions to society and to the theater world about what constitutes truly human life and what keeps people from living that type of life. - What types of plans do you have in the area of international exchange?

- In specific terms, we have formally established a cooperative agreement with the National Theater of China and are presently talking about what our exchanges will include in the future. We have also begun talks with the New National Theater in Tokyo about a cooperative agreement, although the talks are still in the preliminary stage. These agreements are the beginning of our efforts to build a framework for theater exchange programs in northeastern Asia. From this framework I want to see us establish programs of mutual performance exchanges in northeastern Asia and also platforms for discussion. I want to see us shake up the order of Western European hegemony in the performing arts and establish new aesthetics for the performing arts of northeastern Asia.

That doesn’t mean that we will negate good works of the West, however. For example, in Eastern Europe there is a grand tradition of theater with its true inherent value that has survived the dramatic changes brought about by 20th century capitalism. We will be open to exchange with any organization or company that deals seriously with the questions that have been consistently at the core of theater since its birth, such as the problems of human relations, the problems of humanity and history and the questions of theatrical forms.

One of the exchange projects we are working on currently that will be realized later this year is a production of Woyzeck directed by a Polish director. And in June we had a project named “Asia Now Theater” consisting of drama reading of works by playwrights from China, Taiwan and Iran. The Nobel Literature Award winning writer Gao Xingjian took part in that program and as a result of that we are now talking with him about future exchanges. - Would you tell us something about your plans for your 3-year term as artistic director of the company?

- When I took the position of artistic director I made it my goal to return theater to the people. That means to have people experience theater as something familiar and close to them. To do that, we have to create good works and make people feel that they want to come to the theater again. We have to take the initiative to make a diagnosis of the problems of Korean theater and then make a prescription to cure its ills. This entails the full spectrum of issues involved in theater, from the performances to education and cultural policy.

- I want to thank you for taking time from your busy schedule to grant us this interview. I often go to the red buildings of the National Theater Company of Korea to see performances or attend workshops and I sometimes have meetings with people while drinking coffee under one of the parasols in the garden. Every time I am there I am inspired to see the lively faces and figures of the people of your company coming and going. I look forward to your activities in the future.

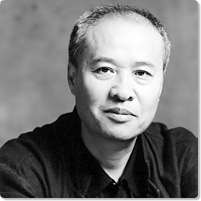

Sohn Jin-chaek

Re-launched as an independent organization,

the National Theater Company of Korea

Sohn Jin-chaek

Born 1947. Sohn Jin-chaek is known in Korea and abroad as a director who brings traditional Korean performing arts methods into contemporary theater works in effective ways. After majoring in theater arts at Sorabol College, he participated in the founding of the theater company Minye and made his directing debut with the company in 1984 with the production Seoul Maltugi . In 1982 he studied for one year at the Royal Shakespeare Company in the UK. In 1986, Sohn started his own theater company Michoo, for which he has directed numerous works since, while also managing the Michoo Studio, the Michoo Actors School and the Michoo Orchestra. Since 1981 he has also organized the annual Madang-Nori festival presenting a variety of traditional Korean performing arts. In its 30th holding this year, this festival draws more than 200,000 visitors annually and has become one of the popular events of the Korean New Year’s season. Sohn has also played a prominent role in national events, including serving as chief director of the Han River Festival of arts and culture accompanying the 1988 Seoul Olympics and directed the opening ceremony for the 2002 FIFA World Cup. N addition to his theater directing, Sohn has also played a leading role as a festival director and artistic director for a number of performing arts festivals. Currently he is artistic director of the National Theater Company of Korea.

Interviewer: Kyoko Kimura, Seoul-based coordinator and translator

*Madang theater

Madang theater is a form of theater that carries on traditional Korean performance arts in the contemporary context and is characterized by a use of caricature and satire to criticize current affairs and societal wrongs and thus perform a social role as relevant popular theater. Another characteristic is the tendency to employ the group dynamics and communal nature of traditional performance arts to create active and communal type communication with the audience and to play with time and space in flexible ways. Traditionally, Madang theater has been performed outdoors in places like town squares (madang).

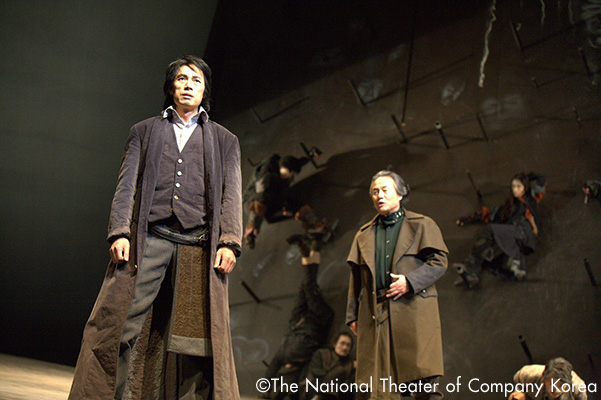

The national company’s inaugural production of Oedipus Rex (Myeongdong Theater)

The National Theater Company of Korea building

Theater Pan

The Declaration of the National Theater Company of Korea inside the company building. The production

March Snow

celebrating the opening of the Paik Sung-hee/Chang Min-ho Theater

A regularly scheduled performance of Kitchen

(Myeongdong Theater)

Related Tags