Yokohama Dance Collection since its inception

- In its 26th holding this year, the Yokohama Dance Collection has been virtually the only international dance festival held in the greater metropolitan area of Japan’s capital. For many years, it has contributed to the advancement of Japanese contemporary dance by serving as the main proving ground for new dancers and choreographers among other things. I have watched its development from its inaugural holding and the way it has vividly shown the changes of the times through changes in its own contents (*1). This year, in addition to the established Competitions I and II, it featured performances by last year’s award winners, the international program (changed to recorded presentations due to the coronavirus pandemic) and symposiums, compositional instruction courses and more.

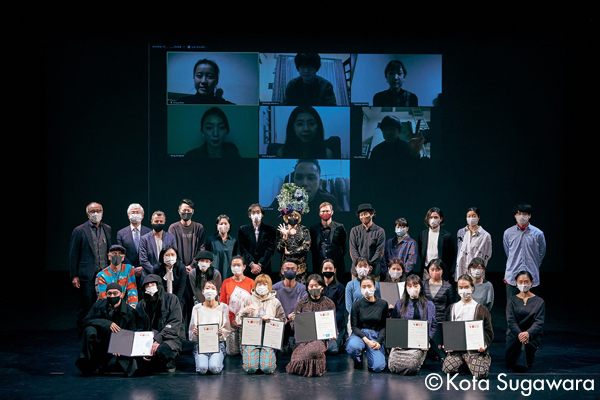

- This year the Collection had to be held in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, but as in years past, the two competitions were held with Competition I for accomplished choreographers and Competition II for emerging (25 and under) dance artists. For Competition I there were 83 applicants from 12 countries and regions, from which 10 finalists from four countries were chosen to compete in the final performances. Due to restrictions on travel, the performances for judging included full-stage recorded video presentations. They were last-ditch efforts, but we received some comments that they showed the way to new possibilities.

- As a new program beginning this year, you started a “Choreographer Course for Compositional Development.” Since overseas dance professionals are know to point out that Japan has many good dancers but the ability to develop dance pieces is weak,” this seems to be a course that truly addresses a pressing need.

- We had a program for past Dance Collection prize winners in which Akiko Kitamura served as facilitator and the Belgium-based choreographer Alain Platel and Korea’s Kim Jeaduk served as mentors to help a group of six Japanese choreographers go through past works and re-compose them. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, Platel and Jeaduk couldn’t come to Japan, but they agreed to hold online lectures and workshops, etc., instead to give the participants an opportunity to observe their choreographing approach and personal histories.

- I would like to begin by looking back over the history of the Yokohama Dance Collection. When the first edition was held in 1996, the venue was not the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No.1 like today but the Yokohama Landmark Hall.

- That’s right. At the time of the launch of the Yokohama Dance Collection, “DanColle” as we call it, also served as the “Japan platform” for France’s Bagnolet International Choreography Award (hereafter: Bagnolet), and from 2000 it became the focus of attention as the “Yokohama Platform.” From 2002, when the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1 opened as “a space that creates bustling activity and culture at the harbor,” that became the Collection’s main venue.

- At the time, Bagnolet was recognized proving ground for contemporary dance artists, and when Saburo Teshigawara won an award there in 1986, it opened the way for him to become an internationally recognized performer. This marked the birth of one of the few platforms from which Japanese dance artists could move on to the world stage, and it became the focus of much attention for Japanese dance artists to follow in the footsteps of Teshigawara, so to speak. However, the first Bagnolet invitational platform was actually held at the Aoyama Round Theatre in the Kodomo no Shiro children’s amusement facility in Tokyo’s Shibuya district.

- To begin with, the start of everything came when Takaya Seiji, a member of the Bagnolet Arts Evaluation Committee and producer of the Aoyama Theatre and the Aoyama Round Theatre, moved to establish a Japan invitational platform for the Bagnolet International Choreography Award (Bagnolet). I am told that it was also in collaboration with another member of the Arts Evaluation Committee, Ko Ishikawa of the Yokohama Arts Foundation (also Director of the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1 from 2003) that the two organized the initial Yokohama Dance Collection.

- At that time in Japan, the very term contemporary dance had not even come into common use. So, Bagnolet and the (Yokohama) Dance Collection became the guiding beacon that led Japan into the age of “contemporary dance.”

- It was from there Japanese dance artists like Kim Itoh, Tsuyoshi Shirai, Hiroaki Umeda and others emerged to become recognized international artists. However, in 1996, Bagnolet changed from being a competition to become a festival, and with that, the Yokohama Dance Collection had to consider moving in the same direction. It was from there, in 2000, that the move to adopt a “Solo x Duo Competition” format was adopted and the “Embassy of France Award for Young Choreographers” that enabled young Japanese dance artists to win residence opportunities in France was established, and new programs other that performances, such as workshops, became and added focus of the event.

- With these changes in the programming, the event’s name was also revised with the addition of an “R” at the end to become the Yokohama Dance Collection R in 2005 and then adding a “EX” to make it the Yokohama Dance Collection Z in 2011. Finally, it returned to the original Yokohama Dance Collection in 2016.

- In the “R” period, the Collection sought to pioneer a role as an Asian dance market, and in the “EX” period, the “Competition” program was established to cultivate emerging choreographers. The practice of inviting more guests from overseas festivals also took hold, and new awards were added that included support for overseas artistic activities. Also, from 2011, new synergistic effects were also achieved through tie-ups with TPAM (International Performing Arts Meeting) in Yokohama that began to be held at the same time, which gave more overseas performing arts professionals exposure to Japanese dance artists.

- The tie-ups with overseas festivals also included more than just awards, such as the new HOTPOT East Asia Dance Platform that was launched in 2017.

- The HOTPOT East Asia Dance Platform was established as a tie-up between Yokohama (Dance Collection), Hong Kong (City Contemporary Dance Festival) and Seoul (SIDance), to be held each year on a rotating basis between the three cities. In the 3rd holding last year, it was sponsored by Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1 in February and featured performances of 12 works by choreographers based in East Asia. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, some companies were not able to come to Japan.

The reason we started HOTPOT is that from the connections we built up with the international dance community through Yokohama Dance Collection, we felt the need for a platform to support the activities of Japanese and other Asian dance artists. The idea was to invite directors and dance professionals not only from Asia but also from Europe and North America to discuss issues and have exchanges with. In addition, we have also begun collaborative efforts with the Kinosaki International Art Center and the Europe-based Aerowaves network dedicated to introducing young artists worldwide. Also, we want to continue to actively engage and cooperate with Asia Network for Dance (AND+), a platform whose core members are contemporary dance professional active on the front line in Asia. - Since TPAM (International Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama) moved from Tokyo to Yokohama in 2011 and is now held at the same time as Yokohama Dance Collection, you have continued to work together in a close relationship, haven’t you?

- As a sign of its intent to strengthen its bonds with its diverse stakeholders here in Yokohama, TPAM changed its name and restart as YPAM (Yokohama Performing Arts Meeting) as of December 2021. For this reason, Yokohama Dance Collection wants to take this opportunity to further deepen its bonds with them next year, beginning from December. In this way, we are always thinking about ways to use our strengths to build our programs in an integrated, multi-layer fashion in order to open up dance to society at large in more and more ways.

- By the way, in your capacity as Director of Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1, you started a new Choreographer System as of the end of 2020.

- It may sound close in image to the associate choreographer systems adopted in Europe, but what it involves is our soliciting applications from choreographers based in Japan and abroad and select ones to work with us for a period of two years. In specific terms, the system involves giving the choreographers a budget of up to 2 million yen a year to support their creation and staging dance works, and in addition to that, in conference with the professionals from our various departments, we will record and publicize the various activities in creating and staging works, educational programs and community outreach programs. For this new Choreographer System we had about 40 applications and we are now in the process of selecting our first choreographers for the program. We hope that by connecting to the world through Yokohama Dance Collection and HOTPOT East Asia Dance Platform, this new Choreographer System will help us strengthen our ties with the various cultural institutions in Yokohama and the local community.

- Next, I would like to ask you about your personal background. What was your first encounter with contemporary dance like?

- Actually, my first encounter with contemporary dance came quite late. When I was at university, I had numerous opportunities to work with a group who were studying production, which got me interested in that work, and while still in university we started a production business. But when I reached the age of about 25, I wanted to begin exploring other areas, and I was fortunate to have the opportunity to go to New York and see musical productions there. At the time, there were many interesting musicals playing on Broadway, like The Phantom of the Opera and Sarafina, so I was going to the theaters quite often. That led me to the feeling that I wanted to be involved in Theater in some way.

- So, your initial encounter with the performing arts came through musicals, didn’t it? About how long did you stay in New York?

- It was about a year. It was just about the time of the passing away of Japan’s Showa Emperor (Hirohito) in January 1989. After that, on invitation from the Japan Traditional Arts International Exchange Association, I was given the opportunity become involved in doing surveys on overseas traditional arts and to invite performances of them to Japan and organize overseas performances for Japanese traditional arts companies. Through a variety of programs, I was also aided by the people of The Japan Foundation. The 1980s were a time when there were a lot of attention on programs promoting international exchange in the arts and culture, and there was also a worldwide renewal of interest in the traditional arts, while most of the research I did was in Asia, I also had opportunities to go abroad to do surveys in Spain, France and other countries. I worked there for about 13 years. When I think about contemporary dance now, it may that my experiences from that time inspired my interest in artists who, at the time, were working in their own localities to develop their own unique choreographic language.

- When you look back now on your more than 10 years in the field of the traditional arts, what are some of the things that left the strongest impressions on you?

- In today’s coronavirus pandemic, I particularly think about the nature of traditional Japanese arts such as Kagura and the like. It makes me think again about the spirit of the performers who carried their tradition by dancing even when there was not even a single spectator there to watch, and the meaning in such local traditional arts. During the first half of the 2000s, I worked with the cooperation of Susan Barge (an American dancer active in the nascent period of France’s contemporary dance scene) to create a production of Iwami Kagura drum performance to be performed in France and Japan, and I think that may have been one of the experiences that made me think about its meaning most deeply and certainly left a big impression on me.

- After that, you moved on to work at Aoyama Theatre. How did that shift come about?

- There was an international event organized by World Folkloriada, an official advisory body to UNESCO’s International Council of Organizations of Folklore Festivals and Folk Arts (CIOFF). It is festival that gathers performers of a variety traditional folk arts designated Intangible Cultural Heritage arts from some 80 countries, and plans call for its 6th holding to take place this summer in Ufa, Russia, after being delayed for one year by the coronavirus pandemic. In 2000, this festival was scheduled to be held in eight venues around Japan, centered on Tokyo’s Shibuya district, and I became involved as a producer. The Aoyama Theatre and the Aoyama Round Theatre were among the organizers chosen, and we were given the role mounting performances and other programs, and this was the first time that I met Seiji Takaya, who was the theater’s managing director.

- Seiji Takaya-san was a figure who left a big mark on Japan’s dance world. In 1986, he established the Aoyama Ballet Festival at Aoyama Theatre, and he helped bring the final competition of the prestigious Prix de Lausanne (Lausanne International Ballet Competition) to Japan. This was one of only three times that the final competition was held outside of Lausanne in the competition’s long history, with the other two being in New York and Moscow. In the early years of contemporary dance, Takaya established the Japan Platform for the Bagnolet International Choreography Awards, and he also began the Dance Biennale Tokyo, which was at the time practically the only international dance festival in Tokyo. With efforts like these, he pioneered the environment to nurture Japanese dance. Unfortunately, Takaya passed away in 2010.

- Takaya-san was a producer of grand scale. He believed that it was important to build a base of support for Japan’s contemporary dance artists as well as those of other genres, and that led him to establish the Japan Platform to select dancers for Bagnolet, and he succeeded in doing that in 1991. After that, the second Japan Platform was held at Sogetsu Hall in 1994 and from the third holding (1996) it moved to the Yokohama Dance Collection.

- The Japan Platform was an innovative event that opened up a new era in Japanese dance. The first winner was Mika Kurosawa, and the second time winners were Toshiko Takeuchi and Kota Yamazaki, and later other young artists like H.ART CHAOS and Akiko Kitamura followed.

- Amidst such a background, you became a producer at Aoyama Theatre from 2001. I believe you made that move in the middle of preparations for the holding of the Dance Biennale Tokyo to be held in 2002.

- We began those preparations as a team of three, including Takaya-san, Kumi Hiraoka and myself. At the first Dance Biennale, the artists invited from abroad included Ohad Naharin, Amanda Miller and John Jaspers, and the participants from Japan included Tsuyoshi Shirai, Ikuyo Kuroda, Un Yamada and Takiko Iwabuchi, and a total of 24 artist/groups performed over a period of 11 days at Aoyama Theatre and Aoyama Round Theatre.

- That was the first time that such a large-scale international dance festival had been held in Tokyo, so it had a big impact in society. For young dancers it was like the light at the end of a long, dark tunnel, bringing the feeling that at last they had a big stage of their own to perform on.

- When Tsuyoshi Shirai’s Study of Live works Baneto “Living Room” that won an award at the 2000 Yokohama Dance Collection was performed two years later at the Biennale, we began to be more conscious of the possibilities of cooperation between festivals. We had that performance in the 1,200-seat Aoyama Theatre, and Takaya-san was the kind of producer who never feared big undertakings like that. I believe it was because of his strong determination to bring contemporary dance to that level.

Things had begun to change, but there was still an awareness that Japan was still lacking in the infrastructure to support the creating work of the dancers. I personally felt that it was my role to seek out public-sector support to enable continued holding of the festival, and thinking about a number of conditions involved, we changed the cycle of the festival to make it a Dance Triennale held once every three years from 2006. - In 2002 and 2004 it was held as a biennale and in 2006, ’09 and ’12 it was held as a Triennale. Lack of public funding had always been an issue, but amidst such conditions, some theaters like Aoyama Theatre and Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1 had struggled on. Channels for overseas exchange were opened and when necessary staff were even sent along with the artists to serve as interpreters to support them. For young dancers with no staff of their own, this was surely a big help.

- Unfortunately, these kinds of conditions perhaps haven’t changed much to this day. I certainly have regrets myself, but I think that in Japan and in Asia, not enough has been done to develop the creative infrastructure and environment to support the dance artists.

At Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1, we are looking for ways to create programs on multiple levels and consolidate them as systems. Of course, all systems soon become outdated and there is a need to keep updating them based on societal trends. But, in Japan and in Asia as well, if we don’t find partners that we can work together with, it doesn’t result in lasting movements. It would be good if we could create choreography and dance centers at the national level where creative work and research as well as promotion and archiving are conducted along with scholarly efforts are conducted, as they are in a country like France, but there are still many difficult hurdles that stand in the way. One of the possibilities is perhaps to have places like Yokohama can take the initiative to set up systems or organizations, and then the national government can come in and provide support. - Is it the case that unless you initiate something and achieve some level of success with it, the national government will not move? If it hadn’t been for the way Dance Biennale Tokyo led to the creation of connections between artists and the birth of networks among theaters, and even though they don’t lead to the forming of associations and the like, an organized movement to improve the environment for creative activities would not have taken place?

- That is a point that leaves a lot to be regretted, and it is unfortunate. From the 2nd Dance Biennale Tokyo in 2014, we spoke with Hiroyuki Kobayashi-san (current President of SPIRAL) and Maki Miyakubo (Director Dance Nippon Associates) of SPIRAL theater, which is also in Aoyama, and made an agreement we organize the festival together. This was a case where two bases in the Aoyama district of Tokyo, which had become a center for culture in areas such a fashion, worked together to expand their combined scope. However, although we were looking to support the activities of dance artists, at that time there was still no real concept of forming an organization that brought together professionals involved in dance. Now that we find ourselves under the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, the failure to create such a coalition at that time has cast a dark shadow, I believe.

- At Aoyama Theatre, other than the festival, you were involved in organizing a number of programs focused on dance.

- Believing that creating dance works at the theater and then having performances of them was a way to build a stronger creative environment, we started a series of performances of new pieces named “TOKYO DANCE TODAY,” which was held at a pace of about twice a year. Also, in order to promote discussion and exchange between young Japanese and Korean dancers, we started the “KOREA+JAPAN Dance Contact” program organized jointly by theaters in Japan and South Korea and held alternately between the two countries. We also planned a program in which theaters in Seoul, Montreal and Tokyo each chose artists whose works would then tour the three cities, and it was planned not as just as a tie-up between the theaters but also to take a form that would encourage collaborations between the artists.

- Then came the sudden announcement that the Kodomo no Shiro facility that had played such an important role in the promotion of dance would be closing. On September 28, 2012, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Education announced that the facility would be closed by the end of March 2015. With this, the Association for Child Development that ran the Kodomo no Shiro announced the closing for January 23, 2015, and eventually it was closed on January 30th of 2015.

- The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s announcement appeared in the newspaper the day after the conclusion of the 2012 Dance Triennale Tokyo, and not only myself but everyone around me learned of the closing at that time. Although people at the top of the Association may have been discussing it before that.

- It was an announcement that came just as the Dance Triennale had become the focus of so much attention, not only in the dance world but in the society at large. There were also some ambiguities about the reason behind the closing, and there was a signature-gathering protest movement and a lot of news about it in the media. There were also numerous opinions flying about how the remaining real estate would be used, and that continues until today (as of March 2021).

- It was truly shocking news at the time, but looking back at it now, it seems to me that the theater there should have been used with a broader vision concerning its programs. Ever since its opening in 1985, it had offered attractive programs in the theater, dance and music fields, and its efforts in the area of nurturing the next generation of artists were also highly praised. However, it might be said that there was a lack of efforts to connect across a broader range of society, and a lack of efforts to communicate with its various stakeholders, which is regrettable.

- From the time of the closing of Kodomo no Shiro to your move to Yokohama, what kinds of activities were you engaged in?

- From 2014, the name was changed to Dance New Air (DNA), since I thought that an international dance festival based in Aoyama could become the core of contemporary dance development in the greater metropolitan area, I was looking for ways to keep the festival going. Then, in May of 2015 we launched Dance Nippon Associates (DNA) as a general incorporated association to serve as the festival’s mother company for its executive committee, and with solid cooperation from SPIRAL, we had an organization to keep the festival going

- Would you please tell us in specific terms how festivals can be used to develop the creative infrastructure and environment for dance artists?

- Festivals can be said to be devices that can go beyond existing concepts and boundaries. And besides presenting performances, they can offer a wide range of opportunities for exchanges and workshops, programs for building new audience, etc., as well as offering places and funding for ideas for creating new works and cross-over collaborations. There is just such a wide range of things that festivals can do, and all of these things can contribute to developing the environment for the artists’ creative activities. Especially with artists based in Japan, I have always tried to share the risk to enable them to be experimental and adventurous with the work they present at festivals.

- After that, you were given the position as director of the administrative office of the giant citizen-participation type festival Dance Dance Dance @ Yokohama (hereafter DDD) that the city of Yokohama launched.

- About three months before the closing of Aoyama Theatre, I got an offer to take that position. I already had a connection with Yokohama through the festival, and I had been a member of the jury for the Dance Collection Competition I since 2011. I worked until March 31st of 2015 on the closing of Aoyama Theatre and then from April 1st I started working for the Yokohama DDD. The DDD festival started in 2012 and was held once every three years, so when I started in 2015 as the administrative director, it was for the second edition of DDD. The festival was a long one that ran from August 1st to October 4th of 2015.

- In all, DDD attracted total audience in the millions, and the program was also incredible with more than 200 works,(*2) making it a festival with a completely different concept that the Dance Triennale you had worked on.

- That’s right. Of course the dancers’ performances were the core of the programming, but there were also public participation events at places like street venues and courtyards of commercial facilities, and we also placed a lot of importance on things like stages where amateurs and pros danced together in genre-less dance styles and programs to nurture next-generation artists. In a broad sense, I think it amounted to activities with the overall aim of spreading dance culture throughout society.

- That certainly sounds like a positive response to what you mentioned earlier about your regrets of not having done more at Aoyama Theatre to open up dance to the communities and society at large, wasn’t it?

- Yes. In 2015, when I actually became involved in DDD, it made me really happy. There were a lot of programs where artists went to schools to instruct dance workshops, and throughout the two months of the festival there were events that made use of public spaces to open up dance to the public. To be able to have dance events like that taking place in venues around the city each weekend is something that is very difficult for one theater to achieve. It was something that was only achieved by having the various departments of the city government working together, and that convinced me anew of the power of the local governments. Yokohama may be a special case, but everyone involved is very serious about the work they do. Even people who are newly appointed to the department in charge of DDD take about three months to go around and see numerous dance events to get the basic knowledge so that they can join in the programming of public participation events, performance programs and promotion. It is truly amazing to watch them.

Going forward, I think it is important for us to build strong lateral bonds between the numerous festivals and other events taking place in Yokohama. For example, there is one of Japan’s largest Jazz festivals, the “Yokohama Jazz Promenade,” and I wonder if we can’t set up an arrangement were the audiences can go back and forth between it and the other dance and performing arts festivals that are going on. I wonder if there aren’t ways that we can get more people like university students and employees of the companies in the Minato Mirai are to be actively attending performing arts events. I wonder if we can use things like games and ICT (Information and Communication Technology) to create collaborations between the artists and corporate employees and students. We have now begun work to create dialogue in these directions. - Then, in 2016, you became director of Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1.

- Originally, the Red Brick Warehouse housed the customs offices of the new Minato Wharf warehouse complex. Now it has become ordinary property facilities of the Port of Yokohama. Now the Red Brick Warehouse No. 1 is run by Yokohama Arts Foundation for the purpose of bringing vitality and culture to this area of the harbor by using primarily its second floor as space for exhibitions and the like and the 3rd floor as a hall for performances of dance, theater and live music event.

- Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No. 1 has until worked in cooperation with the Yokohama Dance Collection, HOTPOT and AND+ we mentioned earlier, as well as DDD and TPAM to build the infrastructure and environment for dance creation on a number of levels over the years. Would you tell us something now about your vision for the future?

- I believe that many of the creators working Japan’s contemporary dance world are ones with their own unique choreography language who are now active around the world. Certainly, in the past, there was a period when the mainstream influences ran from the West to the East, but from now on I think there will be a growing number of dance creators who will learn from the examples of the traditional arts such as Japanese traditional dance (Buyo), Noh and also from Japanese folk performing arts, and having grasped an understanding of these traditions and their histories, we will choreographers who will pursue their own new choreographic language and dance artists who will create dance that deals with social issues and local issues. And, with regard to dance artists in Asia, we want to talk with and strengthen cooperative relationships with the creators and the professionals who are active on the front line. At the same time, we want to help build a richer culture of dance and choreographic language in each of the regions and create platforms that encourage discussion and exchange. And we are linking these activities with HOTPOT East Asia Dance Platform and with AND+ (Asia Network for Dance).

- Another reality that the dance world faces is the lack of accessibility regarding the folk performing arts that remain in Japan’s localities and contemporary dance, and furthermore, folk performing arts have limited access to performance halls that tend to belong to the local communities.

- I think this situation has to change. I feel that in Japan there are not many dance creators who are working with a real grasp of not only the folk performing arts and traditional Japanese dance (Buyo) but also with the modern and post-modern dance movements. So, I feel that another important theme to address is a re-examination of the traditional arts and the history and social factors surrounding them.

- In Japan’s contemporary dance, because of the lack of means for younger artists to become familiar with the masterworks of the movement’s early period, a state of discontinuity is already forming. On the other hand, compared to 30 years ago when the dance market was virtually monopolized by the West, there are now contemporary dance cultures in many Asian localities that are growing independently, and we are beginning to see a growing network of theaters and festivals. We are also beginning to see exchanges between dancers in Asia to the point that I believe we are finally seeing the emergence of dance that is firmly rooted in Asian history. So, movements like HOTPOT and AND+ are really becoming important. And to further strengthen the infrastructure and environment for dance creation, we are going to make platforms for nurturing the next generation of producers too.

- Whenever you are undertaking something new there will be times when help from people from the outside with proven skills will be necessary, but I believe that in order to ensure the continued existence of the systems and organizations that are formed, it is necessary to take measures to ensure that producers can act independently as producers. In the Yokohama Arts Foundation there is a department dedicated to nurture specialists in the arts and culture that has begun activities in training, evaluation and actual fieldwork. The Foundation sends producers to each of the specialized agencies involved in the arts and culture, and in the dance field, there are two producers, Katsuhiro Nakatomi and Anna Nakaso, who serve as coproducers for the Yokohama Dance Collection.

- This year Yokohama Dance Collection will once again be heavily affected by the coronavirus pandemic. Are there any lessons that you have learned from these conditions?

- I believe that we will have to continue evaluating the risks involved with the pandemic and taking appropriate countermeasures. One of the things that this pandemic has reinforced our awareness of is the importance of discussion with others. Since we didn’t have the opportunity to interact with others through the receptions that have been part of the Competition programs, we made a time period after the performance jury session for the jurors and creators to talk with the artists, and that turned out to be a very positive thing. Those discussions helped deepen mutual understanding for both the creator side and the viewer side, and it gives birth to new ideas for activities for the future. Also, with our Master Class for Choreographers, we had not only discussions between the facilitator and mentors and the choreographers but also, we created an opportunity for all of the participating choreographers to share tips for re-composing their pieces, which proved to be very valuable. I want us to continue this type of discussion program in the future.

Also, considering the fact that the pandemic is going to continue for a while longer, we have begun efforts to find ways to use digitalization to a greater degree in the creative process for new works. Although it is still in the conceptual stage, I want to see us prepare a presentation environment with video and virtual reality and the use of avatars that can be used to create game-like dance creation. It would also be interesting it we could talk with members of AND+ to get presenters from Hong Kong, Singapore and other places to join us in this development effort. - In the Yokohama Dance Collection Competition II (young artists) this time, there was one Encouragement Award that went to work submitted as a video recording.

- There are some works with concepts that are so clear that they can be communicated by video, but it can also be said that one of the great appeals of dance is that it is an art form with elements that can only be communicated and experienced between the dancers and a live audience. It is also said to be an art that is only complete when there is an audience to view it, so I think it is very important that we continue to increase the value of the theater to the point where audiences want to clear the hurdles that may arise in order to be there to share the same space and time with the performers and the rest of the audience.

- The coronavirus pandemic has led to a giant boom in the popularity of free streaming of dance films online, so some people are pointing out that this can reduce people’s motivation to go to the theater.

- Videos of break dance that are now so popular may get another boost when break dance becomes an official competition category at the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris. Also, in a Japan we have seen the launch of a professional dance league called D.LEAGUE. I think this kind of base has been evident since the popular introduction of rhythmic dance as a subject in junior high schools after the 2008 revision of Japan’s educational school course guidelines. These developments in the Olympics, in dance videos and in rhythmic dance classes in schools are surely leading to a growth in the dance base on a larger scale. But this is not all there is to dance. That’s why I want to continue to work hard to help build the type of environment that encourages the creation of all types of dance expression based in originality, and the kind of environment that connects this talent and professionalism to society.