- Let me start with a question about yourself. How did you get interested in theatre?

-

My interest in theatre first came through studying English literature in the secondary school when I was 13 years old. I enjoyed it a lot. We had three books to study for the first year but my school was very special and had eight supplementary books to read and write a book review on. This means we read 11 books a year, which is quite a lot for the kids of that age. That made me interested in reading about the people from different cultures. The interest kept growing through my pre-university and university periods.

Although there was no Theatre Studies program when I was at the National University of Singapore (NUS), I always wanted to stage a play. But, I had no confidence. Then in my second year, there was a drama competition. My friend said, “Let’s do one before we leave the university. If we’re too late, there will be no more opportunity.” I agreed. We picked up Woody Allen’s play God , and totally adapted it into the Singaporean context. People were laughing from the beginning to the end and we won the outstanding production award.

Nevertheless, there was a sense of dissatisfaction after that – we felt that our adaptation of a foreign play, especially something like Woody Allen’s work whose success heavily relies on typically New York kind of neurosis, missed our cultural roots. So I started to think; What if we adapt it more deeply – or even do our own new work? - Then you started your own group.

-

Yes. After the competition, I told everyone in the group that I wanted to start a group. We also invited people in other groups in the competition. I wanted to form a group because, I think, I wished to have a group I could belong to after graduation.

We had to find a name for the group. Someone said, “How about Necessary Theatre?” I liked the word “necessary”, and another person suggested “The Necessary Stage (TNS)”, which sounded more layered. We got excited with that, and the new company got a name.

Then we needed to decide what to do. We all agreed that the focus should be on local works with our own metaphors and images. After studying western literature, I was quite envious of them. I felt we did not have our own voice. Actually, there was a lot of negativity toward doing original works when we started the company in 1987. There were no established methodologies to develop them, and thus it was much safer to stage the tested foreign scripts. At the very beginning, we did not have fixed roles in the company. We shared the role of director, playwright and actors, and then improvised. Thus, the sense of collaboration was there by default at TNS.

Things became a bit more complex because there was the Marxist Conspiracy and detention in 1987 (*1) . We were asked a lot of questions before the authorities finally approved our registration as a society. They asked why we wanted to do local plays, because they were suspicious that we were planning to stage subversive political plays. They also questioned why all of our Executive Committee members were Catholics. Because of the involvement of the church members in the Marxist conspiracy case, they were cautious of the Catholics too. Actually, I did not realize it until they pointed it out… It was only because we were old friends from the same Catholic junior college! - It is interesting to learn that TNS was seen with such a political perspective from the very beginning of the history of the company. How did TNS develop after that?

-

Around that time, there was a platform called Singapore Lunchtime Performances. NUS had one, and commercial companies like Shell and Development Bank of Singapore held their own lunchtime performances at their own small venues located in the city centre. A lot of amateur theatre performances, including ours, were staged there. The fee was very small, but it was truly a nurturing environment for young practitioners. Even after many of us graduated from NUS, we still performed several times on campus as well.

It was a time when there were very few theatre companies in Singapore. Newspapers covered us, there were no competing shows, and people come to our show. We started as an amateur on-campus group, but gradually developed to a semi-professional and to a professional company.

In the meantime, we also developed our own method of work – the collaboration and device way, and Haresh Sharma, who is now a co-artistic director of the M1 Singapore Fringe Festival, became a resident playwright of the company. In creating our local works, we heavily involved actors in the process, and workshopped the script with them. Thus, Haresh’s writing method was not a traditional one done at his desk but more like a theatre-making experience.

One of our most successful early productions, Lanterns Never Go Out (1989) was created as one of the lunchtime performances, but after being restaged 6 times, it was invited to the national Singapore Arts Festival . The cycle of restaging, workshopping, listening to feedback, and improving the work started to be formalized as a method of TNS.

All of this happened as the theatre scene in Singapore was being professionalized. In 1991, National Arts Council (NAC) spun off from the Ministry of Community Development and the government started to commit itself in the arts in the long run. Then we started to leave our daytime jobs and became doing theatre fulltime. NAC had a policy to privilege the groups doing local plays to nurture local arts. For example, their Theatre in Residence scheme that let you rent a theatre for free requested the grantees to produce four plays a year; at least two out of four had to be local plays, and the other two could be either local or foreign. Of course, it was too good a deal to miss for theatre companies and a lot of people started to force themselves to do local plays. It was a huge turn of events, and TNS grew up in the arts scene that was evolving. - What was the biggest challenge for TNS in last 26 years?

-

I think it was censorship. We deal with local issues, atmosphere and environment, and create socially engaged works. Our productions are neither entertainment nor purely personal psychological stories. They always have a social edge. In the 1980s, that kind of theatre was heavily criticized – other artists consider it less artistic counter-propaganda, and the government was concerned with the way the controversial issues were presented in the works.

Things were very difficult because when we dug deeper into the issues, we needed to explore the various causes of the social problems. For example, Off Centre (1993) was a story about mental illness. It had to talk also about the element in society that was not compassionate enough to accept the people with mental illness who wish to be reintegrated into the community. We needed to look at the root causes that made up Singaporeans who were then solely driven by the ethos of productivity. You cannot avoid that. But, this made our works more controversial.

Although the authorities started to encourage the arts, they were not ready to accept works that were critical about the society and themselves. So, it was difficult to negotiate with them. Authorities were very nervous about being represented in a negative light. In Off Centre , the middle-ground authority was uncomfortable with the story because the protagonist broke down in the army. Initially, it was commissioned by the Ministry of Health, but they did not wish to sponsor a play that put another ministry – Ministry of Defense – in a bad light.

We did not want to change the script, so eventually the Ministry of Health decided to accept our proposal to take back the sponsorship money and let us go on with the play. The actors had spent nine months for research and rehearsals, and they all agreed to cut the fees. Thus, we decided to go on. Then the government got paranoid. “Where do you get money from?”, they asked. They did not understand our passion and instead investigated us, suspecting that we were funded by a foreign agency! We had to realize that this kind of thing would always be with us as long as we do local works. - Along with the local plays, intercultural/international collaboration is one of the main pillars of TNS’s current works. How do you maintain the coherence in your artistic vision?

-

In the 1990s, we looked at Singapore as multicultural, multilingual and multi-religious. We were celebrating difference and brought in actors from different ethnic backgrounds. At the same time, we were also looking into the marginalized minority groups. What we developed through these projects is our relationship with the others – those who were different from us and often less privileged. We faced problems about how to represent them.

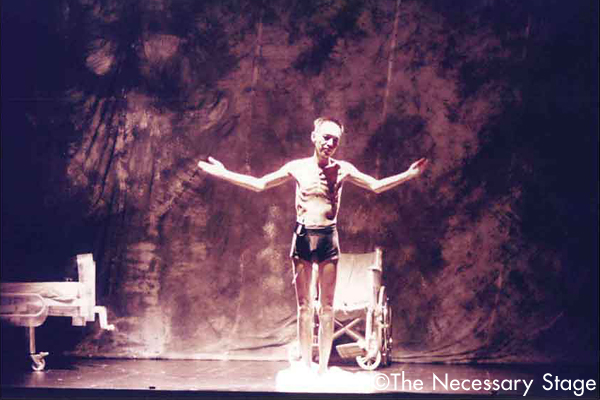

In 1998, we created Completely With/Out Character with Paddy Chew, the first Singaporean who made his HIV positive status public and became a poster boy for the HIV issues. After collaborating with us in the process for one year, he himself was on stage. It was a very special play because there was no “actor” – he subjected himself. Dual performances were going on. Audience watched him performing the task, but even after the curtain went down, he could not escape from his illness. He had his own story to tell, thus our collaboration was meant for structuring it and giving it dramatic worth. We decided to use simple multimedia just to assist his storytelling.

Through such experiences, we learned how to deal with the others, how to represent them and how to involve them into our artistic process. We kept “othering” everything – performers, audiences and environment. When the otherness is perceived in the process, it will always problematize and complicate things. Such complexities of difference are now beginning to be the issues we have to address in this globalizing world. And the complexities at home, dealing with the multicultural, made us ready to go into regional and international activities.

Again, NAC’s policy affected us. Under the initiative of Goh Ching Lee who was the director of Singapore Arts Festival at NAC then, it introduced a grant scheme for international collaboration in the 2000s to encourage Singaporean artists to co-produce works with their foreign counterparts. There were theatre companies who wanted to do it like us, and NAC responded to such demands. It became a great help for us to pursue this direction. - Then TNS started M1 Singapore Fringe Festival in 2005. How did it start?

-

Singapore’s telephone company M1 has long been sponsoring us. It started when one guy named Chua Swee Kiat who had once worked at Shell moved to M1. One day we got an email from him saying; “I got money. Do you want to do a festival?” He watched our lunchtime performances at the Shell venue and was convinced that TNS would be a good and responsible partner to handle it. Of course we said, “Yes!” That time we wished to have a youth festival because NAC had just closed down its Young People’s Theatre program after struggling to make money. We believed that there should be a platform for the young, and we named our festival

M1 Youth Connection

which was launched in 1998. After a while, we struggled to bring in young adults as the audience because of the word “youth”. Our main audience was kids. So we renamed it to

M1 Theatre Connect

in 2004.

In that one year, we suddenly felt the change in the scene. It was very quickly being internationalized. Everything became international. NAC’s mission statement also changed to incorporate an agenda to develop Singapore into a global city. So we wrote to M1 and suggested to change it once again to M1 Singapore Fringe Festival. First they were reluctant because we had just changed the name, but we persuaded them. I believe it was a right decision. Since then the festival has been more internationalized and media started to cover it more seriously. - Every year you set a theme and participating works in the Festival are selected according to it. What is the idea behind this policy?

-

We wanted our festival to be socially engaged, the same as TNS. We wanted a festival that could inscribe a presence of the arts on people’s minds. Thus we decided to set a theme. We understood that our approach was against what the “fringe” had been. People come to Edinburgh Fringe to rebel against the curated Edinburgh Festival. So, at the beginning, people asked us, “What are you “fringe” to? Why is it curated and you claim it to be a fringe?”

Some artists criticized us for partnering with established institutions such as the largest theatre venue in Singapore, Esplanade Theatres on the Bay . Esplanade had been known internationally by 2005 and many groups applied because they wanted to perform there. So, in a way, it is true that we were piggybacking on Esplanade. Critics said, “How come Fringe can happen at established institutions?”

Our response to such criticism was like this: Singapore has such a strong mainstream culture, thus we artists inevitably rebel against our mainstream culture throughout the year. We do not have to counteract the established Singapore Arts Festival. We do not have to stay distant from Esplanade. Rather, we should engage with them. They have resources that you can put some fringe programs into. What’s the point of standing aside and criticizing them? It is our festival and we do not have to follow the colonial definition of fringe. We rebel against the very idea of “fringe”.

We do not want only one kind of fringe – something like “avant-garde fringe”, “social works-only fringe” or “fringe filled with community works”. We want to show that fringe can be diverse. Therefore we curate, and look for a balance. - The theme of the 2014 festival, which will be held from January 8 to 19, is “Art & the People”. What are the significant characteristics in this edition that marks the 10th anniversary of the festival?

-

It would be the interactivity of the works. The introduction in the program booklet reads; “By re-examining the relationship between Art and the People, we open ourselves to new possibilities of the definition of art and creative process”. To explore this, we selected works that involve people in many different ways.

For example, The Mountain by Singapore’s The Art of Strangers brings 15 performers in a mix of storytelling and role-playing on the theme of climate change that allows audiences of only 15 people. One performer to one spectator. The show will bring each member of the audience an intimate theatrical experience. Zeitgeber by Takuya Murakawa of Japan also focuses on intimate interactions between the performers and the audience members. Each performance will see one of the members of the audience taking a role of a severely disabled person, and experiencing the communications with the caregivers only through his/her eye movements.

Another project from Japan, Majurah Singapura – Tree Project by Hiroshi Sunairi involves Singaporeans in a different manner. Sunairi has distributed seeds of trees that survived the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, which are known as Hibaku trees, and has invited them to grow the seeds and nurture the seedlings. The exhibition will feature these seedlings along with the photographs and video interviews from former enactments of the Tree Project that have happened around the world. - How do you balance between international programs and local ones?

-

The festival has become higher in stature because it is international. And, within that stature, we commission local artists. Foreign artists often bring works that have already been presented and tested. It is easier to source funding from embassies and grant-making foundations for such works. Of course, at the same time, we wish to see international works that are not featured in the established festivals. So, there is a mix.

But for our local artists, it is more difficult to get sponsorship. Thus, we commission them. It is not only for the emerging artists. Veteran artists also want a platform for more experimental work. Fringe has found a role to encourage process work. We get assets from the richer side of Singapore, such as Esplanade, and use it to support creation by the local artists. It is a Robin Hood kind of idea, I would say. - The programming of the festival has changed significantly since its launch. For example, the first festival had seven categories while the 2014 edition has only three (*2) . How have you developed the programming?

-

Yes, we once had a lot of programs! I remember the second edition had 52 events in total. It was also an experiment. Just before that, we visited

Sibiu International Festival (ARTmania Festival)

in Romania, which had 300 events. Literally people were running from one theatre to another. It was so vibrant. We wanted to try to create a similar atmosphere in Singapore.

After all, this experimentation of having 52 events did not work at all in Singapore. People just did not know which one to go. There was no focus. In Sibiu, the festival was one big event in the town and there were no other festivals. And all neighboring countries looked forward to the event. But Singapore had so many festivals back to back. Many people felt that year’s Fringe had too many programs and made them feel that everything flew over their heads, and they decided to give this festival a skip. They always have another one even if they miss ours. We never repeated this template.

We gradually simplified the structure. We took away the film portion because other film festivals became very popular in Singapore. The idea behind it was, as the co-artistic director Haresh once said, that we were not aiming to make it big but aiming to make it deep. Actually, people asked us whether we were making next year’s festival bigger to celebrate the 10th anniversary. But we are not going in that direction. We want quality and each event should have an experimental and exploratory value to it. This will make the works impact the people and people will remember them. - You once introduced a “Virgin/Veteran” labeling system to indicate the accessibility of the works, but you stopped it a few years later. Was it another experimentation?

-

We introduced the system because we were afraid that audiences might choose something that would destroy their interest in fringe works if we did not quote the works properly. So, these labels, which were something like a “spicy/not spicy” indication on the package of curry paste, would help the audience to make a right choice.

However, after a while, critics and reviewers found that the festival had reached the point where people would be able to take accountability regarding the shows they were going to. One critic said to us, “Just lose it. Labeling is too paternal.” He felt it went against the whole spirit of the fringe. He insisted that people should take a risk and we should trust the audiences to be resilient enough. We agreed and decided to take them away. - I suppose the very nature of the fringe has caused a tension between the festival and the authorities. Were there any cases where you had to confront the authorities? How did you manage to handle them?

-

Yes, of course, there has always been a tension and there were some instances of conflict. Censorship has always been an issue. TNS itself also has staged some shows that touched sensitive issues in the Fringe. So we set up a kind of communication channel with the Media Development Authority (MDA), which is in charge of censorship. They also wished to avoid going through everything laboriously and wanted us to tell them which shows were very “safe” and which were a bit more controversial. That was a bureaucratic side of it. We agreed to just do that because we knew it would eliminate a lot of work.

Sometimes MDA did not know how to make sense out of the works. In such cases, they came to talk to us and we went through the story with the MDA officers. We would not mock them, look down on them, make fun of them or patronize them. Sometimes they in turn helped us. Returning to their office, the officers needed to report to their bosses. If they were clear about the story and our intention, they were able make a case on our behalf. They would become very important representatives. Different artists would have different attitudes towards the censorship mechanism. We have chosen to – kind of – cooperate with them and to have faith that they have artists’ interests in mind as far as they possibly can.

We found an interesting approach to censorship in one of the performances to be staged in next year’s Fringe, Three Fingers below the Knee by Portugal’s Mundo Perfeito. In this work, the artist took works that were censored during the dictatorship and made a play out of them. The point they wanted to make is that the censors became playwrights in this project! Because the censored texts used in this production are all from Portugal and not from Singapore, the threshold is higher. However, when you watch it, naturally you start to think of censorship everywhere, the philosophy of censorship and the impact of censorship on making art. - The Complaints Choir Project which was one of Festival Highlights in 2008 and Finnish artists collected complaints from Singaporeans made it into a choir piece. I heard it had trouble with the police.

-

In The Complaints Choir Project

, we were supposed to have several outdoor performances at various locations including a park and shopping centres. It was a concept that the artists had used in other countries and Singapore was the first Asian country to host the project. They auditioned people, workshopped with them, generated the complaints text and rehearsed for the performance. It was a real fun work in which a country could laugh at itself.

There were, as expected, one or two lines dealing with Singapore’s Central Provident Fund (CPF) system. (*3) Then it became complicated with the police, because they did not want the foreigners in the choir to sing those lines. After the meeting with them, I went back to talk to the choir, which was made up with Singaporeans, permanent residents and foreigners, and informed them of the situation. Everyone, especially the Singaporeans, wanted to stay together because they had been working together for two weeks. And of course, as an organizer, I wanted it too. At that time, Singapore was talking about being a gracious society. Now the Singaporeans were told to say, “Hey, we wish to sing in this choir. Can you foreigners leave now?” How gracious is that?!

MDA staff members actually defended us. They talked to the police on behalf of our project all the way until the very end. We tried hard to find what could be done to make this event happen with all of the choir members. Finally the main venue of the event, The Arts House said, “You can do it here. Cancel all the other venues.” And, we also proposed to turn it into a private event for invited people only. The guests were personally invited and asked to register at the door. It was meant as a form of double security. I informed the MDA of it, the MDA informed the police of it and everything was settled.

But, everybody did not know that some film crew had come with the artists to document the process. They recorded this private event, and the next day, after the festival ended, it went out on YouTube. (*4) And it was internationally covered. But no complaints or penalties came from the authorities – we did exactly as we were recommended by the police in order not to go against the required law!

When many reporters and journalists called us after that, we kept saying, “No comment.” We had done what we had to do and we thought the organizers should not defend it. It would discredit everything if we complained. Rather, we thought we should let the other parties defend it. Actually when the story came out in the papers, many Singaporeans living overseas wrote in to condemn the action. - Isn’t it a big burden for a private theatre company to handle such a large-scale annual international festival?

-

Not really. We have already got a strong administrative team working throughout the year and we have a template. Once there is a template, you can tweak certain aspects of it and you are not starting from scratch. More importantly, the support from the venues that are co-presenting the shows has helped us a lot. And. it has been continuing to grow. For example, the new National Art Gallery, which is opening in 2015, has already approached us to say, “Hey, there’s a venue for your Fringe”. We can feel the support. People want the festival.

Actually, we wanted to close the festival at one point. But a lot of people said, “Don’t close!” So we had to change our minds and now we are considering rotating the artistic directorship of the festival. Haresh and I will be out, probably in 2015. After that, there will be a new artistic director every two years. We have listed some names and the diversity of them is quite interesting. This does not necessarily mean we will change everything all together – the new artistic directors still have to respect some features of our template and the administrative team will remain.

We feel there is a strong need for curators in Singapore now. Singapore Arts Festival was privatized and Ong Keng Sen, the artistic director of TheatreWorks, became its first director. But who is next? We need to nurture festivals curators. Maybe the Fringe can have a role in helping to develop them. - There will be a major change in the festival soon. Can I conclude this interview by asking your plan for the future?

-

We realized that we have not collaborated with local groups for years. We feel now that theatre groups in Singapore are going into pockets – working only with their own actors, with their own audience and in their own corners – because it is easier. Haresh and I want to break down that wall. We want to do intercultural works with local collaborators. In multicultural Singapore, it is possible. This is our current interest. It might not be permanent, but at least for the next three to four years, this will be our focus.

Our new scheme called the Lab, which will be held in conjunction with the Fringe, will be the platform for this. I have not yet sort out the template, but the rough idea is that it will be a place where people gather just to jam. Haresh and I had an experience of that kind of a jam session. When we worked with a Croatian company, our collaborators could not come to Singapore, thus the creative team in Singapore – a multimedia artist, a musician and two of us – came together and did multiple experiments with projection, music and other elements. There was no end product. It was truly a breath of the fresh air because we had no pressure to use it for anything. We just experimented with whatever we wanted to try.

We want to bring it back. Then, after working for a while, it may reach a tipping point where we can say, “OK, we should graduate this process into a project”. Maybe yes, maybe no. And those who do not get anywhere can fall out and regroup in another way. I wish to ask the future artistic directors of the Fringe to have one segment for these Lab presentations.

The Lab is not going to be dominated by TNS. Other theatre companies also have programs for theatrical experimentations. If we can invite these people and put three or four works-in-progress created out of these programs under the umbrella of the Lab Report in the Fringe, it could be another significant feature. The shows really do not have to have any arrival point. They can be something like what the New York-based The Wooster Group has been known for. Talking about their The Hairy Ape , the audiences would say, “Oh, which version are you talking about, the spring version or fall?” They pay money to watch the work developing. When would this happen to us? We wish to have audience members participating, giving feedback and contributing actively in developing an art work. The Fringe can platform this as a Lab Report . I am starting to prepare for the first Lab Report in 2015. It has to be a playground. It is meant for playing without the pressure of economics or performance indicators!

Alvin Tan

M1 Singapore Fringe Festival

approaching its tenth year

(C) The Necessary Stage

Alvin Tan

Co-founder of Necessary Stage and co-artistic director of M1 Singapore Fringe Festival

Singapore is known for its national-level initiatives to bring arts and culture to its citizens, such as the Singapore Arts Festival and the Singapore Biennale. A unique presence among these festivals is the M1 Singapore Fringe Festival launched in 2005 by The Necessary Stage, a theatre company known for its social engaged works and for its collaborative work with foreign artists.

Interviewer: Ken Takiguchi

*1 Singapore government undertook a covert security operation in May and June 1987, under which 22 people were arrested and detained without trial. They were accused for their alleged involvement in a Marxist conspiracy to subvert the existing social system in Singapore. The detainees included Catholic Church workers who were considered as the core members of the group and theatre practitioners from a local company called Third Stage. Third Stage was known for their original local satirical plays that often criticized unpopular policies of the government.

*2

The 7 categories in 2005 Fringe were; 1) Live Fringe: theatre, dance, music and other live performances, 2) Celluloid Fringe: films, 3) Fringe Gallery: exhibitions, 4) Fringe Demonstrations: interactive public events, 5) Fringe Speak: talks, discussions and workshops, 6) Fringe Conjunction: outreach programs organized in collaboration with other groups, and 7) Industry Fringe: a platform for the exchange among art practitioners. The 3 categories in 2014 are; 1) Fringe Highlights, 2) Live Fringe and 3) Fringe Gallery.

*3

CPF is a compulsory savings plan for working Singaporeans and permanent residents. A certain percentage of employee’s monthly gross salary is automatically deducted and saved in a special account, which can be used primarily for his/ her pension, healthcare and housing. It is sometimes cited as proof of Singapore being a “nanny state”.

*4

The video can be accessed at; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3S0mEJ-aajM

The Necessary Stage

https://www.necessary.org

M1 Singapore Fringe Festival

https://www.singaporefringe.com

The Necessary Stage

Completely With/Out Character

(1998)

(C) The Necessary Stage

The Art of Strangers

The Mountain

(C) Phorid

Takuya Murakawa

Zeitgeber

(C) Ryouhei Tomita

Hiroshi Sunairi

Majurah Singapura_Tree Project

Related Tags