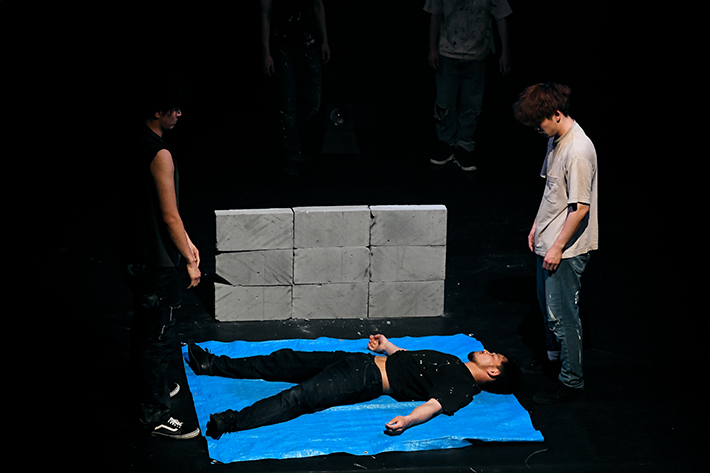

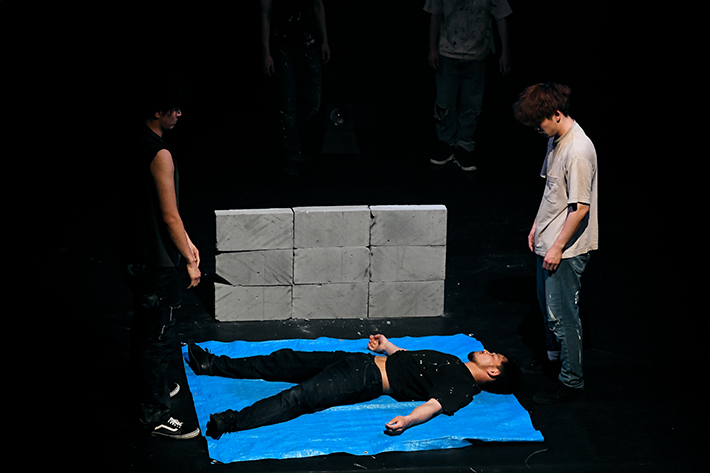

F/BRIDGE

(at Coronet Theatre’s “Electric Japan 2022”, May. 2022)

Dance that born of the relationship between “object and the body”

Irradiating society, the choreographic art of Koichiro Tamura

Koichiro Tamura (born 1992) commanded the attention of the dance world by winning consecutive awards at the 2016 and 2018 Yokohama Dance Collection. Born in Niigata Prefecture, where Noism is based, Tamura went from dance club activities in high school to beginning artistic activities in Kyoto, with its culture rich in opportunities for genre-crossing exchange. As in his representative work “F BRIDGE” which has male dancers in dirty jeans and T-shirts pacing with concrete blocks on their backs, and in the duo piece “goes” which makes use of car tires, Tamura presents works born of the relationship between “object and the body.”

F/BRIDGE

(at Coronet Theatre’s “Electric Japan 2022”, May. 2022)

Yard

(at Yokohama Dance Colletction “Dance Cross + Asian Selection”)

(Feb.2017 at Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No.1, 3rd Floor Hall)

Performer: Rino Yamamoto, Koichiro Tamura

Photo: bozzo

https://youtu.be/lMT1d7089QU

F/BRIDGE

(Jul. 2020 at Kinosaki International Arts Center)

goes

At Yokohama Dance Collection 2021 “Master class for Choreographers”

(Feb. 2021 at Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No.1-Steep Slope Studio)

Photo: Yulia Skogoreva

STUMP PUMP (first performance)

(Feb. 2019 at ArtTheater dB Kobe)

STUMP PUMP TOKYO

(Mar. 2022 at Kichijoji Theater)

Photo: Marika Ishida

Kubochi (nostalgia)

At “Contemporary Ballet of Asia 2022”

(Nov. 2022 at Gangdong Arts Center, Seoul)

Photo: Rachel Na

*1 The All Japan Dance Festival – KOBE (AJDF)

AJDF was established in 1988 by the Japan Women’s Sports Federation, Kobe City, and the Kobe City Board of Education. It was the first nationwide creative dance competition in Japan for students enrolled in high schools, universities, and junior colleges. Held every August, there are two categories: the “Creative Competition Division” for creative dance pieces which have not been previously performed at other events and are performed by teams of five persons or more and less than 30 persons, and the “Participant Presentation Division” open to participants performing various types of dance. Among the participants are many professional dancers and choreographers.

*2 a photograph taken by photographer Kevin Carter during the Sudanese Civil War

Carter won the Pulitzer Prize for this but committed suicide one month later after being accused that “Should have helped the young girl.” Later, there was a controversy with testimony that the vulture just happened to be photographed at the moment it appeared, after which it immediately flew away.

Related Tags