Baobab Re:born project vol.6 Please! Laughing Frame

Director / Choreographer: KITAO Wataru

Presented by: The Japan Foundation

Wataru Kitao

Wataru Kitao’s “Mind Beyond the Frame”

Driving Baobab and Dance × Scrum!!!

Photo by Kenji Kagawa

Wataru Kitao

Wataru Kitao (born 1987) is the leader of the dance company Baobab and is active as a choreographer, dancer and actor. When Baobab’s Re:born project vol. 6 Please! Laughing Frame was released on the online project “STAGE BEYOND BORDERS” (https://stagebb.jpf.go.jp/en/) launched by the Japan Foundation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic for the distribution of works with multilingual subtitles, it gathered the attention and support of the younger generation, eventually recording about 300,000 views (the “Frame” in the title refers to a picture frame and the content is a video version of Baobab’s repertoire work “Laughing Frame,” depicting the urge to “transcend the frame” (and confining frameworks such as dance genres), which Kitao explains in the opening solo interview before moving on to self-introductory interviews with dancers in a Japanese-style tatami room seated in omiai (matchmaking) format, and then progressing to their dancing and eventually moving to an airport under travel restrictions where people have disappeared due to the COVID-19 pandemic, where Kitao and the dancers break into an energetic group dance).

Interviewer: Takao Norikoshi (dance critic)

- You are involved in various activities other than your dance company Baobab, and you often participate in theater performances as an actor and choreographer. Of particular note is the festival “DANCE×Scrum!!!” (hereinafter Scrum), which you established as artistic director when you were 28 years old. Scrum was started in 2016 as a biennial event at the Toshima Ward Public Theater Owlspot, and it celebrates its fourth holding in July of this year. Could you explain the framework of the festival?

- To begin with, I started out with the idea that it would be nice to create a place where artists could meet, compete together, and perhaps become rivals. At the same time, I wanted to eliminate as many of the barriers as possible between the artists and the audience, and to see if it was possible to build a borderless relationship with them, like the players form a scrum in rugby. In the past three holdings of the festival, there have been a total of 41 groups performing, for a total of more than 150 artists, and we have met a total of more than 1,000 spectators.

- How do you choose the performers?

- There are artists we send out offers to and artists we select through an open call format. In the first two editions, we set an age limit of under 35 years old to concentrate on younger people, but from the third time, we abolished the age limit. We’re getting older ourselves and the content of Scrum is becoming more diverse.

The artists we send offers to are ones who have continued to be involved with Scrum and who understand the intention and temperament of the festival. However, we maintain a fluid system to keep a good balance of participants so that there will always be new encounters. With regard to the open call selections, have chosen new participants each time. In the 4th edition, there were about 30 groups that applied, ranging in age from 19 to 50 years old, including online applicants. The number of performers from the open call has increased from 11 to 14 and then 16 groups for the first three holdings, and this time there were 20 groups, including the online program. The scale of Scrum has also increased, so I think it is time to think about the next developments we should undertake. - It is popular not only to perform on the theater stage, but also for mainly young people to perform in the foyer space?

- The festival started as a co-hosted project with the Owlspot Theatre (although the 4th festival was hosted by Baobab alone), so I wanted to use the entire theater. We had the artists choose where they wanted to set up their own acting areas freely in the foyer, and then we had the audience roam around freely and watch what they liked. With this method, the way the artists show the part of the foyer they have chosen then also becomes an important element of their works. I thought that this would provide a good opportunity for the audience to encounter the excitement and passion of dance up close in person, and that they could become immersed in the dance while going back and forth between the foyer and the theater.

- This certainly must be a very good experience for young dancers. I find it amazing to see how the performers are also very enthusiastic about finding the best way to use the different spaces.

- I think that’s one of the most significant benefits of making it a festival. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to maintain social distancing, and for that reason we had little interaction in the foyer in our 2020 edition. So instead, we launched an online program.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, many festivals were held online, but how did you approach the online program?

- We recorded the performances in the theater and released the edited footage online, not only in Tokyo but also throughout the country and the world. When I actually tried it, I felt that in the coming era there might be artists who would now be interested in the possibility of approaching dance through the media of video. I would also like to find out about such a change in awareness concerning online distribution of works, so I am working on online distribution as a central part of our program again this time (2022) in addition to the theater program.

- When you first started Scrum, you actively called for “interaction with artists of your own age” every time you were interviewed. Kitao-san was born in 1987, and there are many dancers who are active in your same age group. Yuri Furuie (1983), Yo Nakamura (1988), Yu Okamoto (1988), Kota Kihara (1988), Mikiko Kawamura (1990), Kaho Kogure (1990), Ayane Nakagawa (1991), etc. You came from a background of child roles in musicals, and compared to that perspective, there was a concern that the world of dance was too lacking in horizontal connections.

- Yes. I thought that dance people concentrated on their individual activities, and there was little interaction between dancers or relationships where they stimulate each other. However, as I continued with Scrum, I realized that in fact it not so. Actually, there was a lot of interaction between dancers, and I began to think it was just that we in Baobab were not connecting to others, and it was as if we were a remote islet…[laughs].

- Ayane Nakagawa, just like you, is a graduate of Oberlin University and she said something similar.

- In addition to the fact that Oberlin University is not very active regarding participation in external events that other university dance clubs participated in, and I was mostly involved in the activities of the theater department, so I had a stronger relationship with them. So, Baobab mostly got invitations from theater-related festivals such as KYOTO EXPERIMENT, Strange Seed Shizuoka, and Tama 1 Km Fes(tival), since there were a lot of actors participating in our works, and we used a lot of dialogue.

- In other words, Baobab was perhaps mostly thought of as a theater company with a lot of dance, rather than an actual dance company [laughs]?

- Maybe so [laughs]. After our performances, I was often told that there was more dance than people had expected. When I was younger, I thought a lot about each festival and made works in order to leave a strong impression, even if it meant compromising on the refinement of the works. I wanted Scrum to be a place for that kind of expression, since there were few places where young dancers could demonstrate pure, outrageous energy, and that is what we wanted to do ourselves. To that end, I think it is important that we have continued to do so.

- Now, especially in Asia, there are many small and unique dance festivals organized by dancers, and they are actively collaborating with each other. In addition to you open call activities, it would be good if Scrum could also connect with overseas festivals, wouldn’t it?

- I really want to do so.

DANCE×Scrum!!! Connecting New Relationships

DANCE×Scrum!!!2020, BaobabUMU -um-fusion edit.

(Dec. 2020 at Owlspot Theater)

Photo by bozzo

- You formed Baobab in 2009, when you were still a student at Obirin University.

- I entered Obirin University with the intention of majoring in theater. In the future, I had hoped to be able to do theater as a musical actor, as an interdisciplinary player, but when I met Professor Kuniko Kisanuki and was so impressed by her that I asked myself if I could make it as a dancer. And when I realized that, I saw that I had been distracted from dancing [laughs]. Originally, I had been doing classical ballet and street dance, and at that time Obirin was quite borderless in terms of dance and theater, so I was also performing as an actor in on-campus performances.

Suguru Yamamoto, who founded the theater collective HANCHU-YUEI while he was at Obirin, was a classmate of mine. We became really good friends from the time I entered the university, and we took the same drama classes and such. At that time, I performed in HANCHU-YUEI performances and I also had him take part in works that I wrote and directed for the university’s regular performances. I should note that at Obirin university we had to do graduation works, and my research theme for my graduation work was the planning and management of omnibus performances by senior students (Baobab’s performance was a work titled Unbalanced), and for it I analyzed how a project could be ongoing and develop in the process. I wasn’t really conscious of the fact at the time, but I think I had a solo Baobab performance in mind, and I was thinking about what kind of performance it should be. - Baobab gave its first performance in the young artist program of KYOTO EXPERIMENT, and counting from there, the number of works you have created must be considerable.

- Our latest is the 14th full-length work since that initial one. There are several versions of several of our works, and every time I participate in a festival, I create a new short work, so if you include our solo works, there must be about 30 works.

- When I saw your performances at the Yokohama Dance Collection and the Toyota Choreography Awards, which are particularly noted as gateways to success for young people, I was impressed by your physical acumen. Your work Vacuum which was selected as a Toyota Award finalist and won the Audience Award, had real impact as a work in which you and your eight dancers, each wearing colorful street style patterned shirts and Bermuda shorts, performed a fierce group dance with you all moving up and down throughout, and it was so impressive in its contrast to other works that were burdened down by their emphasis on concept.

- Actually, vacuum was a work I created at a time when I was experimenting with the relationship between words and physicality, and at first it was more theatrical. Toyota is a dance award, so I reconfigured it to accentuate its dance orientation. When director Keishi Nagatsuka-san, who had seen the original version saw the screening of the video version, he said, “Why did you switch to a dance orientation?” [laughs].

- By the way, Baobab often uses text in his works. Are these texts written by you?

- I gave up theater because I realized that I couldn’t write play scripts. But the texts in my dance pieces don’t tell a plot, rather they must speak words for the body, so I write them myself or together with the actors in the cast.

- Since your first works, the credits you list for yourself are “choreography, composition, and direction,” and we feel that you have a theatrical orientation.

- Well, I like both dance and theater, so I am consciously making works from a broad perspective that can be described as comprehensive art. I choreograph each and every move in a way that also involved space design, and I call this method composition. including choreography and space design. Rather than creating abstract motifs based purely on ideas, I think that solid composition and direction are also necessary, so I guess you could probably say that I am making things in a very theatrical way. Also, because of my personal tastes as a spectacle lover and a science-fiction lover, I want something dramatic at the end, so I have a sense that I am doing something different from the usual territory of choreography.

As for my working method, first of all, I will start with a kind of plot for each scene that includes the music. As I am working, I will add things and rearranged their order until I get the feeling that finally it all comes together and makes sense. However, this way of thinking is difficult to share with dancers in a way that they will understand. But when I have actors working with me, I find that they are much quicker to grasp my intent. When I do workshop-like things because I want to go work outside the box, the actors bring to it a completely different point of view. When the dancers see this, it inspires them, too. They begin to see that their job is not just to move, so they start thinking about what they can do to expand own their individuality and add to the work. On the other hand, the actors are moved by the fascination of the [dancers’] physicality and try to reach a new level in that direction. I think that such openness helps make the work multifaceted, and that is what takes the creative process into the realm of a directing (in the sense of theatrical directing).

In my early works, what was foremost in my mind was the thought of just bringing as much richness as possible to the performance at hand, and to have the audience see how amazing the dancers or actors in our performances were. However, I had a premonition that I would not be able to continue to create works with ideas and curiosity alone, and from around the time of my 2013 work Domestic progress 1. 2. 3 (a group dance using gestures and words that emerged from my motif of What is “domestic?” and adopting a rap format) I gradually began to find ways to express things based on real cues that emerged from the sensations I experienced in my daily life. - In that case, you would be exposing your inner self, wouldn’t you?

- It was embarrassing for me at first. If I put inner self out there [on stage] and it was rejected, I wouldn’t be able to recover from that [laughs]. However, it led to a great increased in the amount of time I spend thinking about my works. For that reason, from Baobab’s 11th main company performance FIELD in 2018 at the Kichijoji Theater (a work where 17 dancers with unique characters engage in physical battles like athletes in sports competitions to the sounds of snare drum and laughter in the background on a stage (field) that is divided up by shifting constructions made of tape and iron pipe) I was asked Shunsuke Nakase-san (*1) to join in as a video artist and dramaturg.

- Why did you decide to add a dramaturg to your creative process? And in what specific ways is Nakase-san involved in your works?

- Nakase-san was very keen in his ability to perceive the intentions of the creator(s) and the artistic aim of a work as a whole. In the past, when I talked to people who are active as dramaturgs in theater, such as Masashi Nomura-san and Kaku Nagashima-san, I was surprised to see that their thoughts reach far beyond the stage itself, and Nakase-san is the same.

I ask him to do research on areas that are beyond my reach, and I also consult with him about the composition of our works. In the rehearsal studio, he is always by my side in the position of powerful assistant director. Nakase-san always grasps the whole picture and he makes suggestions when he feels that a different point of view will be helpful. He’s not a dancer, so I think it’ also important for us that his thinking isn’t specifically focused on dance alone. - FIELD features choreographers Ayane Nakagawa (suichuu megane∞), Shun Nakamura (Bushman), Reisa Shimojima (Kedagoro), Roma(nce) Hashimoto, and others. Around this time, there were many performances by dancers who could create such works. In your 2019 work Jungle, Concrete, Jungle (a work expressing the dynamics of various lives in a space design inspired by cities), 21 people participated, including Yu Okamoto (TABATHA), Ryu Suzuki (eltanin), and Rina Kobayashi (Supponzaru). Are these performers that you sent out offers to? Or were they chosen by audition?

- I sent out offers to the main people, but half of the rest were chosen by audition. Romance Hashimoto-san auditioned for the show and said, “I want to start my own company, so I came to check out a company like this that is active in the theater,” [laughs]. I thought that was great.

At that time, I felt there could be beneficial possibilities in increasing the number of dancers and increasing the size of the group. I wanted to work with a variety of different people, I wanted to try using auditions, I wanted to reach people who didn’t yet know about Baobab…. At the time of FIELD, I explained that I wanted to do a work that introduced the struggles and competition of athletes, and I also wanted to make it a place where lots of creators gather. Then, everyone looked around diligently to find things that they could do, and that made it an extremely creative working environment.

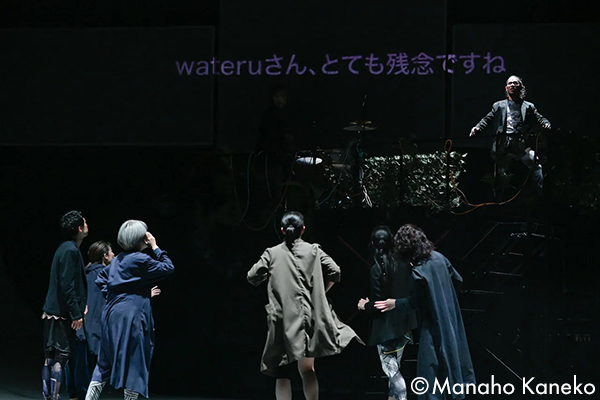

Baobab

FIELD

(Sep. 2018 at Kichijoji Theater)

Photo by Manaho Kaneko

Jungle, Concrete, Jungle

(Oct. 2021 at Owlspot Theater)

Photo by Manaho Kaneko

- Your generation is very close, in that there is virtually no hesitancy for the leaders to interact across the boundaries between companies. In the past, people couldn’t have imagined appearing in a work of another company.

- That’s true. I think there is a lot of exchange now across the boundaries of companies and between artists in general. There are dancers who are borderless, or who call themselves members of as many as four companies, including artist units. Perhaps many more people instinctively feel that there are places or scenes that they just cannot reach by continuing to stay within the boundaries of their own company, and there is a sense of crisis that if you do not go out to various places, you will not be stimulated and energized. I think people like Nakagawa-san and Shimojima-san helped realize this change in atmosphere.

- Another thing that is noteworthy about Baobab these days is its “Re:born project” (*2) series dedicated to the re-creation of past works. This project seems to have thrown a wrench into a major problem that has been cited in Japan’s contemporary dance world, which is the growing obsession with new works and the resulting lack of opportunities to work to strengthen and deepen works after their initial premiere.

- There are works in our repertoire like Please! Laughing Frame, which were created as 10-minute short pieces and remade many times, but until a few years ago, I was also quite a believer in the supremacy of new works. However, after I reach the age of 30, I felt that I was getting worn out. Even if we decided on a concept for each performance, I felt that could serve as roots for further development. Just as if I were dealing with an existing play, for example if we were staging a play by Shakespeare, I would like to see the production become something that would serve as a new guidepost, an accomplishment, for all the people involved in the production, all the people in the company who worked on it.

In contemporary dance, when you create a new work you are always starting from scratch. Even if I have a concept in my mind, when I start the creative process, I have to begin by sharing it with the dancers. So, it inevitably begins like a work-in-progress. I wanted to work to deepen the maturity of those works. Eventually, I would like to do existing works, but since I have a number of my own past works, I decided that I should re-create them first. That’s why I named the series “Re:born” with the image of rebirth of my past works. By comparing my current self with the works I created more than 10 years ago, I thought I could create a solid base that will lead to the future.

Re:born project vol.4-5 Laughing Frame

(Jan. 2022 at KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre – Large studio)

Photo: Hiroyasu Daido

- I would like to ask about your creative method. How do you go about creating movements in your works?

- We do it in various ways, but many of them are done in workshop formats. When I tell the dancers about the theme of the work, I have the dancers fill out a questionnaire. It asks them things like: “What kinds of movements do you need to get your body into an excited state?” If the theme is “cat style,” the dancers and I would create and compare our individual cat-like movements, and we would discuss whether someone’s cat style exceeded their expectations, and what was the difference between the two cat-like perceptions. Sometimes I take inspiration from words and from music, which means that each scene is different. However, in the end I create about 80% of the choreography and give it to the dancers to perform.

- Do the outputs of your choreography change depending on the performers?

- It does change. In the early days, there were times when the themes of the works be changed suit the performers. Now, I hand over a piece of choreography to the dancer(s) at an early stage in a piece’s development, and while sharing my choreographic language, we first focus on creating a common language. Next, I get input from the dancers and then we start a sort of rally where the dancers really express themselves physically.

- How do you design the dance space?

- We are very particular about the dance space, including the stage art and lighting. There were times when the stage art included inclines, but the dancers sometimes complained about the difficulty of moving on slopes [laughs]. I believe that dance should be a comprehensive art form, not just about the body, and I am always thinking about whether I can create a spectacle with dance that flips the world inside out, like the Karagumi company’s Red Tent Theater (the highlight is the “street-stall collapse” where the tent at the back of the stage is opened at the end and the space is integrated with the outdoors) and like the sudden turns of the world in Hideki Noda-san’s plays.

- What about the music?

- I sometimes consult with Nakase-san, but I make most of the decisions about the music. I stubbornly stick to that policy [laughs]. However, I am also thinking a lot about the gap between generations. Students in the first year of junior high school today don’t not know the songs of Hikaru Utada, and some young people get really excited by the music of Steve Reich. I’m experimenting to find out what resonates with people of different ages.

- In Jungle, Concrete Jungle you were broadcasting silly puns against the background of a song by Ed Sheeran, you were really stirring things up.

- There is also a Kansai region-style energy, but there was a reason for that. I wanted to ask, “In the age of TikTok and social media, aren’t you just dancing the same dance to the same music?” So, I did it with the intention of trying to ask how the viewer would feel if I used humor to undermine Ed Sheeran while he’s so in fashion right now?

- How do you see the TikTok generation, which is now becoming a big part of the world of dance following its big impact on the music industry?

- It’s a mix of pros and cons. I am thinking all the time about the difference between dance as a video works and the performing arts as video works, but what is important for me is the three-dimensionality of the body. I was attracted to contemporary dance because of the aesthetic sense of the body as something that can be appreciated from any angle in the full 360-degree perimeter and because of the freedom in space design. But TikTok always has only the perspective of the frontally positioned camera. It’s all about fitting into that angle of view. Of course, it is good that dance becomes more widely popular because of it, and there is no doubt that TikTok is a powerful tool for that. However, I think that dancing only in that world with one angle of view is a little unhealthy for the body.

- It is said that vertical video on TikTok has the effect of blocking out information on the left and right sides and concentrating the viewer’s consciousness on the centrally positioned body. On the other hand, the sense of designing and recognizing the entire space, including the body, which is so important in the performing arts may be lost.

- What irritates me is the live footage of some idol groups. At the risk of sounding rude, I would say that their choreography, which is not complicated as dance, is created by a number of crane cameras moving around to create a video in which the dance formation changes dramatically. So, the camera is doing much more “dancing” than the dancers. Unfortunately, a lot of young people end up discovering dance just by what they see in those idol group videos. I would like to introduce them to the fact that there are other different worlds of dance through my works, as well as through classes at schools and workshops.

- It is true that one of the characteristics of Baobab is group dances that make full use of the stage space.

- By dancing in a group, I want to bring out exciting moments when the body virtually screams out in joy or excitement. In the end, what is needed is chaos, and if it doesn’t happen, you won’t be able to produce enough energy to go beyond the frameworks.

This is also a point that is related to the composition, but in our group dances, I have different choreographies being played out at the same time, so that multiple events are always occurring around the space. Since the viewer sees differs depending on where they are positioned in the audience, I want to make sure that the amount of information contained in the work is so large that it is impossible to grasp everything in one viewing. That’s the difference between a video where the movement can only be seen from a fixed angle of view and live stage dance performance. I am always conscious that Baobab’s works will look different to a friend who is sitting in a different seat, even when we are watching the same work.

Instead of feeling a sense of déjà vu, I try to shift the formations and timing so that the audience will ask themselves why we did it that way, so that the scenes that strike the audience will happen unexpectedly. And when there is a mix of dancers and actors, that causes different types of unpredictability to be created. There are some things that disappear when the techniques are in certain alignments, so the choreography does not have to be neatly aligned. These are things I’ve been doing intuitively since I formed Baobab, and I’m still exploring them consistently today.

The Creative Method

- I would like to ask you about your personal activities. You are currently a member of the Gorch Brothers and have worked extensively as a choreographer and actor in Kaki-Kuu-Kyaku, KUNIO, Kinoshita Kabuki, Lolo and other places.

- Basically, I accept whatever I am asked to do. Directors are more conscious of how to coordinate people (performers), so there is always a lot to learn in different places like these.

- Since you came from a child actor background, you have a long career as an actor.

- That’s right. I was five years old when I first performed in musicals, and it continued almost every year. Without knowing any other types of performing arts than musicals, I spent about a third of my life in that one-sided world. But thanks to that, the places I find myself in now are all full of fresh experiences in terms of both theater and dance, and so there are an unending series of new discoveries for me.

When child actors approach the borderline of adulthood, when they reach junior high school, the roles they can play rapidly disappear. I went to college with the intention of becoming a full-fledged adult actor, and it was there that I rediscovered dance. Since I came from a musical theater background, I had a perception the performing arts as a combination of theater, song, and dance. I couldn’t be excited about a work that didn’t have a fusion of both dance and theater but was only one or the other. When I see a stage like that, I sometimes think, “I wish I could do it this way more,” and I feel that that desire for crossover is the driving force behind Baobab’s continued existence. People tend to think I’m doing this and that, but my logic has remained consistently one of that crossover, that fusion. Without such diverse input, I don’t think Baobab would have the expressive strength it has today. - Tarogo Goriki, who played in Kinoshita Kabuki’s Kurozuka, left a very strong impression on me.

- At that time, I was immersed in Kinoshita Kabuki and Sugihara Kunio-san’s directing methods, and the following year (2014) I released TERAMACHI (a work inspired Kyoto’s Teramachi Street, a place where history and tourism coexist, and the light and darkness of the activities going on there day and night) that was influenced strongly by it. In particular, I found that Kabuki’s “complete copy” (trying to exactly copy the Kabuki actions and dance while watching a video, the purpose of which is not to imitate the classics, but to realize that you cannot copy them with your own contemporary physicality) could be used as a step to remake the classics with the modern body. That made me feel that it was a method that could help me incorporate street dance and other foreign dances into my Japanese body.

- You performed in The Unknown Dancer in the Neighboring Town which was fusion of theater and dance (written and directed by Suguru Yamamoto. It was a one-man stage in which you collaborated by dancing 25 different roles and such as people living in the city, trains, and dogs, while text was projected telling of indifference to others and unconscious violence and more. It premiered in 2015). It was also amazing in that it continued for 90 minutes with constant movement and speech.

- The premiere was really scary, and when it was over my outlook on life had changed. When I invited Suguru-kun to the post-performance talk for Each focus in an apartment – a virtual image he looked at the stage and said he wanted to create a work together with me someday. He said that he felt that when I create my works, I do it with a calm (detached) eye. And he said that he wanted to remove that shackle and delve into my potential as a performer.

- What kind of process did you go through to create the work?

- It was like groping in the dark [laughs]. Even though the text hadn’t been written at all at the time, Suguru-kun keeps bringing up fictional character settings. For example, “Mr. A is 45 years old and single, and he comes to the zoo on weekdays off. His hobby is watching strip theater,” and then he began to choreograph for that character. We did that for characters from Mr. A to about Mr. H, and he choreographed for every one of them. He would then add text to it, and finally he decided which ones to use in the composition.

- You played a number of different roles, such as a non-human train, and at the end you even played “a future child who was never born.” There are works that use text and movement, but it’s miraculous that you were able to collaborate on the whole story and have it work so well. It was really unique from the way it was made in the first place, wasn’t it?.

- It was a feeling of symbiosis and coexistence. When I use words in dance works, they tend to be poems. When you put words to the state of the body, it turns out that way from the outset. However, I had been doing Shakespeare since I was a child and had learned the methodology of Shiki Theater Company, so I had confidence in my ability as an actor to bring a character to life. I think this was a stage that succeeded because of that. It was very exciting, but it felt like running a full marathon, and I might not be able to do it again using that same method.

- You also performed in New York in 2020. You were invited by Yamamoto-san, who had been in New York for six months on an ACC Fellowship, to perform there. You were also nominated for a Bessie Award. Four years after the premiere, the dialogue was completely missing, wasn’t it?

- I stayed alone in Kyunasaka studio in Yokohama to rehearse, so as one could expect, the dialogue completely disappeared [laughs]. However, thanks to the unique creative method I used, when I remembered the movement, the dialogue came out smoothly again. It felt like the movement and words were installed in my body as a set.

This stage was able to be performed just in time, but in 2020, many performances were canceled due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. So, no Bessie Prize or a Grand Prix were given that year, but instead, everyone was given a nomination status. I returned to Japan around January 20, and I remember that there was already “Wuhan” (the initial reported origin of the virus) posted everywhere at the airport.

Expanding Personal Activities

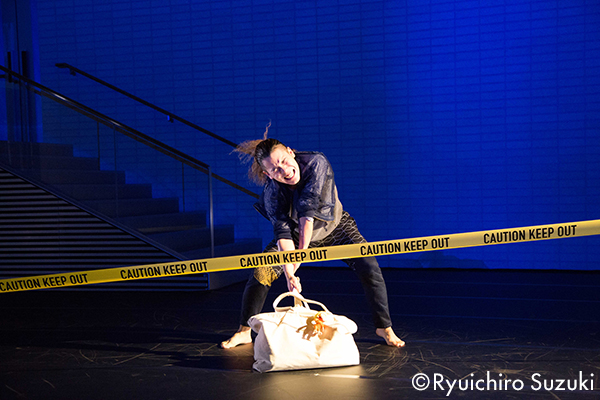

Festival/Tokyo Outdoor Performance Series

The Unknown Dancer in the Neighboring Town

(Dec. 2021 Owlspot Theater – Foyer)

Photo: Ryuichiro Suzuki

- As a creator, what are you especially interested in now?

- I feel very good about the results of our Re:born project, so I would like to continue it. Also, I would like to try using classic music works such as [Ravel’s] Bolero. But that will be after I clarify within myself the meaning of taking on this great piece ….

I’ve always emphasized “questioning and undermining/betraying” things. By questioning and betraying my own ideas I am able to conceive new movement and create new works. Recently, I have been trying to rethink that methodology and way of thinking. Shinji Ono-san of the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse advised me to “try making a statement as a choreographer for overseas audiences,” and I am now working on that. For this purpose, I have one of avid longtime fans of Baobab interviewed me, who is a bookstore clerk who understand us most. - I think that the world your generation sees is different from what the generation before yours saw. How do you feel about the environment in which you dance and the environment in which you create works?

- To be honest, I’ve never participated in a company of a generation that was active internationally and were frequently going around to overseas festivals, so I don’t really know what they experienced. But, three years have passed since I personally and Baobab had finally started to spread our wings overseas, but it was almost immediately brought to a halt by the COVID-19 pandemic. When I was younger, I may not have been very familiar with the dance world, and now I just want to do the work that is in front of me and keep going forward. The saddest thing is that I want to continue but often can’t, and I think that is why I am taking an approach like Scrum with the younger generation.

I wasn’t just looking at dance, I was looking outward to musicals and theater, and I also took on a sense of rivalry and turned to a more aggressive approach. The reason I am involved in a wide range of activities, including entertainment, is partly because I can’t earn enough money just from dancing. But, I also think that my ability to maintain a broad perspective that allows me to connect with artists beyond genres is in inherent part of my character. Appear in a variety of places and repeat my processes of output and input. And I protect the company [Baobab]. I will continue to do that without wavering. - Is there anything particular that you thought about during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- The pandemic gave me time to rethink a lot of things. Due to the cancellation of overseas work, I thought about Japan again. I went to Kochi and Toyama Prefecture as part of the Tokyo Caravan (*3), a project related to the Tokyo Olympic/Paralympic Games, and it was a lot of fun to work with local traditional performing arts and artists from various fields rooted in those areas. Moreover, it seems that the connections started at that time between dance and theater artists there who had not worked with each other before that are now continuing to work together.

We had only gone there as outsiders, but what we created together with the people who welcomed us anyway have resulted in the fostering of new grassroot activities in the area that are now ongoing. This means that a positive chemical reaction occurred! It is part of my nature that it makes me very happy when the new connections we build between people take root and give birth to new relationships. As it happens, my best tool is dance, so I especially happy that it was able to help build positive new connections. There are still many things that I don’t know about Japan and there are still many people I haven’t met, so I feel that there is great potential there for me in that direction. And I believe that if we continue opening doors like that, it will eventually lead to new connections overseas as well.

As for the works created within Baobab, I always want to create output that include new and sharpened refinements. On the other hand, I want to continue to be actively involved in things that broaden the portal of dance and build new relationships with people. Both of these are my sincere wishes for the future.

Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic

*1 Shunsuke Nakase

Born in 1983. Filmmaker, dramaturg. While a student at the Department of Literature at Wako University, he has been involved in video production of live concerts. He circumnavigated the world in 2009 and 2012 and later launched the Performance Project del Toca in 2014. He joined Baobab in 2017 and has been involved in the creation of works there together with Wataru Kitao ever since. In addition, he participated in choreographed works by Yu Okamoto, Akira Kasai, Yo Nakamura, and Minami Nakayashiki as a video director.

*2 Re:born project

Since 2021, under the name “Re:born project,” this project has presented re-creations of the works Unbalanced (2021), Jungle Concrete Jungle (2021), UMU -um-fusion edit./ Please! Laughing Frame (2022, two performances), etc.

*3 Tokyo Caravan

This project was launched in 2015 as a lead-up project initiated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government to lead into cultural programs to accompany the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Based on the concept of “Culture is born where people interact,” a wide variety of leading artists traveled to various places around Japan to develop a range cultural exchange projects.

Related Tags