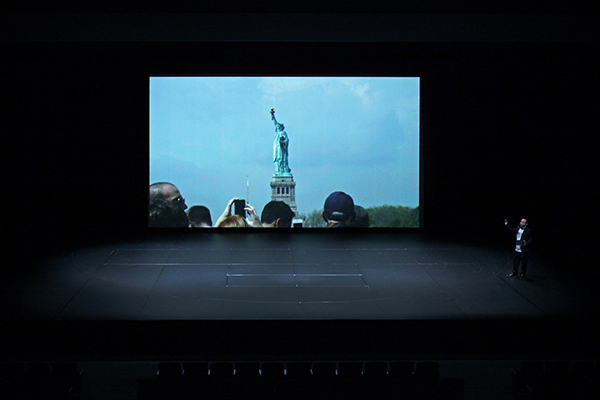

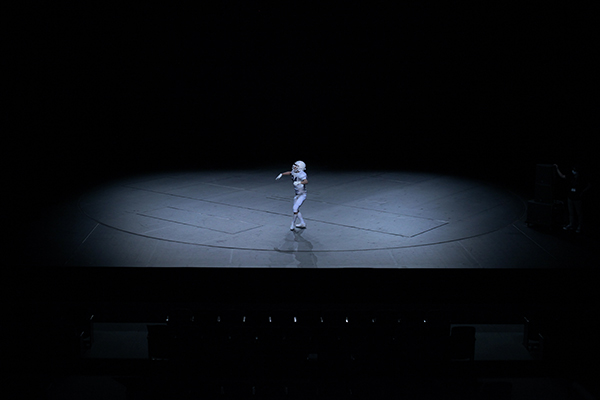

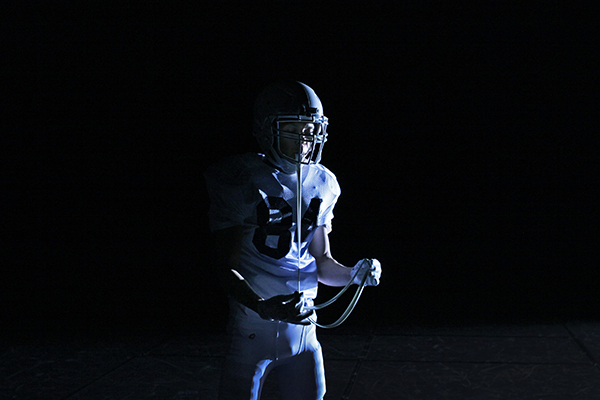

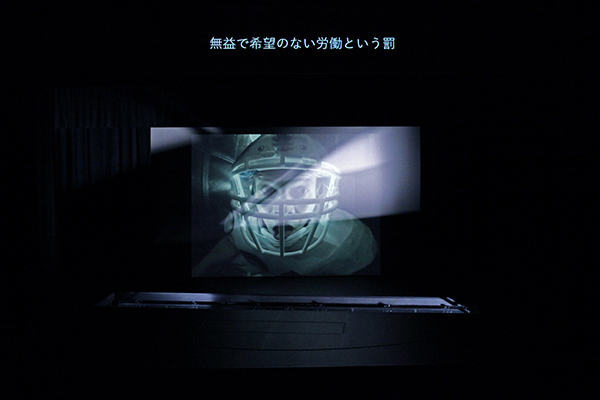

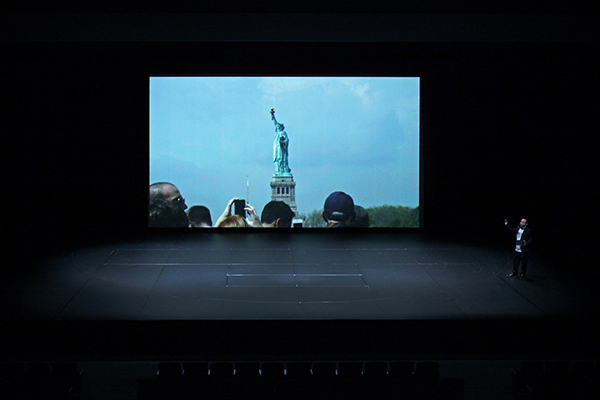

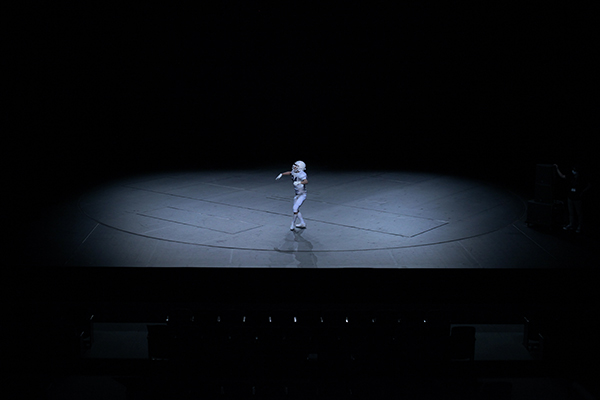

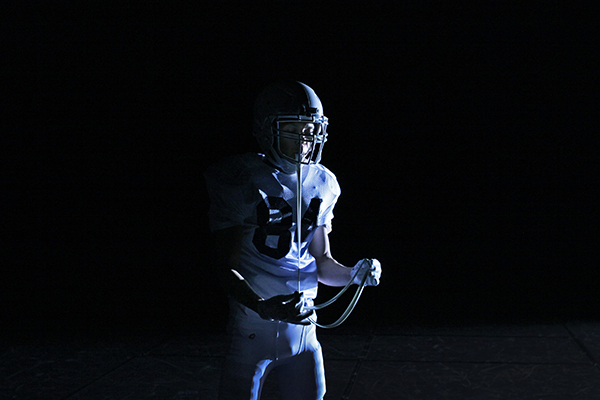

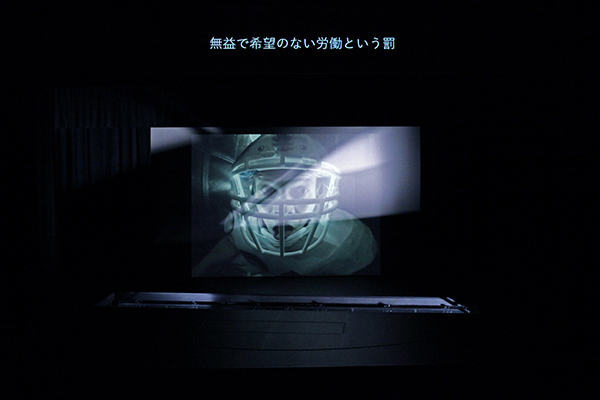

TASTELESS (2021)

Photo: Yuichiro Tamura

Found images and objects inspiring flights of imagination – the method of Yuichiro Tamura

In June 2021, contemporary artist Yuichiro Tamura presented his first theater work, TASTELESS, at Kyoto Art Theater Shunjuza as one of the works on a program commemorating the 30th anniversary of the founding of Kyoto University of Art and Design and the 20th year of the theater (document footage is scheduled to be uploaded on the Kyoto Art Theater’s YouTube channel in March 2022).

TASTELESS (2021)

Photo: Yuichiro Tamura

TASTELESS

Date: Sunday June 27, 2021

Venue: Kyoto Art Theater Shunjuza

NIGHTLESS (2010–)

Photo: Yuichiro Tamura

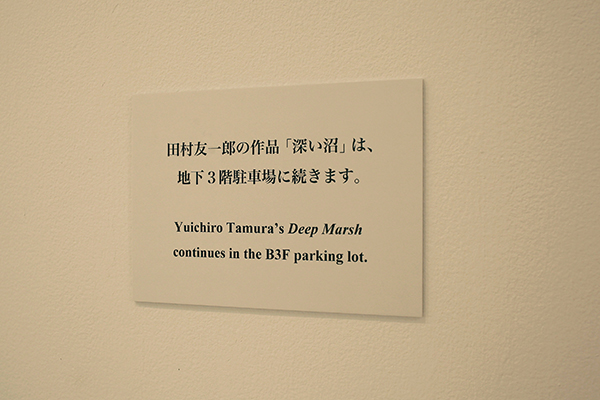

Deep Marsh (2012)

Photo: Yuichiro Tamura

On the Trans-Siberia Railway departing from Moscow headed to Beijing for a project of the Institut für Raumexperimente at the Berlin University of the Arts.

Photo: Yuichiro Tamura

Milky Bay (2016)

Photo: Yuichiro Tamura

Chemistry / The Story of C (2020)

Photo: Yuichiro Tamura

*1 Born in 1930 in Shanghai, James Graham Ballard was an English novelist. He became a leader of the New Wave science fiction (SF) movement in the 1960s and expanded its horizons with his contemporary works, believing that new SF novels should explore not outer space but the inner space of human consciousness. He wrote the semi-autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun based on his experiences in his formative years at a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp during World War II that became a best-seller and was made into a movie by Steven Spielberg. In TASTELESS, references were made to Ballard’s short story The Waiting Grounds (1959) that depicts the cycle of outer space on an alien planet and it is quoted in the performance.

*2 TASTELESS was created in response to an assignment in the theater experimental open-call research project “The Waiting Grounds – Interdisciplinary Efforts to Explore the Present of Performing Arts and Theater” (enacted under research representative Sayo Nakayama) of the certified Joint Usage / Research Center at the Kyoto University of the Arts. Originally the work was scheduled to be performed on Feb. 29, 2020, but had to be cancelled in compliance with government policy released on Feb. 26, 2020 by the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters. After that it was performed on June 27, 2021 as a production of the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Performing Arts.

*3 Ishinha was a theater company founded in Osaka in 1970 with Yukichi Matsumoto (1946-2016) as its leader. The company’s most distinguishing feature was that the actors and the staff worked together to build giant outdoor theaters in vacant lots. The awe-inspiring quality of the stage art they created ranged from realistic sets that rivaled movie sets to very abstract spaces. The company was also known for things like its rhythmic style of delivering lines based on the Osaka dialect and intonation that was dubbed “Jan-Jan Opera.” Since its founding, the company consistently performed original pieces based on themes of immigration and “drifting” in various locations, but the company disbanded on December 31, 2017.

*4 Director Norimizu Ameya, novelist Mariko Asabuki, and others gathered to work onsite on the Kunisaki Peninsula of Oita Prefecture, where they created the 12-hour art tour Irikuchi, Dekuchi. For this tour, Tamura was in charge of creating video/film works including documentation. The documentary was released for sale on Blu-ray and DVD, and also made accessible for rental viewing online.

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/iriguchidekuchi

*5 Koji Return is a documentary film about the “hyakusho” life of Koji Yamazaki (of FAIFAI), based on the fact the original meaning hyakusho, which today means “farmer” in Japanese is actually a word that meant people with 100 (hyaku) family names, 100 house names and perform 100 different kinds of jobs. Yoko Kitagawa (of FAIFAI), Yasutaka Hayashi (of Chim↑Pom) participated as directors, working in the field with Yamazaki on the production. The film was released on YouTube.

https://youtu.be/rTYVlf1EZAA

*6 Magazine House Ltd. publishes POPEYE, BRUTUS, relax, and GINZA, among others. Publication of the culture magazine relax (1996-2006) is currently suspended, but during the period when Hitoshi Okamoto was editor in chief (2000-2004) it was loved by many readers and fans for the unique perspectives of its feature articles on culture, music, and fashion, as well as for the page design by art director Eisaku Ono, and gained a following abroad as well.

*7 Born in 1965 in Tokyo, Yataro Matsuura is an essayist and creative director. After quitting high school, Matsuura went to the U.S., where he became fond of the American bookstore culture, and upon returning to Japan he opened the old magazine store m&co. booksellers. In 2000, he began a truck-based mobile bookstore business, and in 2002, he opened the bookstore COW BOOKS in the Meguro district of Tokyo. Beginning in 2006, Matsuura served as chief editor for the magazine kurashi-no-techo for nine years, after which he joined Cookpad Inc. in 2015. That same year, he started the website Kurashi-no-Kihon. Currently, he is Director of the Oishi kenko Inc. which runs the aforementioned website.

*8 Born in 1954 in Shizuoka, Masahiko Sato was a TV commercial planner at Dentsu Inc. known for his popular commercials like those for the Koikeya “Scone,” “Polinky” and “Don Tacos,” NEC’s “Baza-ru de goza-ru” and Toyota’s “Corolla II.” After he became independent, he continued to work in a variety of fields such as creating the video game software “I.Q.” and the NHK children’s education program “Pythagora Switch.” From 1999, he served as a professor of Keio University in the Faculty of Environment and Information Studies. From 2006, he has been a professor at the Graduate School of Film and New Media at Tokyo University of the Arts, and in 2021, he was named professor emeritus of Tokyo University of the Arts.

*9 Born in 1956 in Tokyo, from the early 1980s Masaki Fujihata produced computer-generated works, and from the 1990s he created a succession of interactive works. In 1996, his work about networks, Global Interior Projects #2, won the Golden Nica prize at Ars Electronica (Linz, Austria). His work on the theme of interactive books, Beyond Pages, is included in the permanent collection of The Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe (ZKM). In 2005, Fujihata took part in the founding of the Graduate School of Film and New Media at Tokyo University of the Arts, and he served as the Dean of Research until 2012. He is currently a professor emeritus of Tokyo University of the Arts.

*10 NTT Inter Communication Center (ICC) is a cultural facility run by NTT East Corp. That opened in 1997 within the Tokyo Opera City Tower in Nishi-Shinjuku, Tokyo. Focusing on the fusion of scientific technology and cultural science, ICC has introduced cutting-edge technologies in media art including virtual reality and interactive technology. ICC also published the journal Inter Communication (publication suspended from Issue No. 65 in 2008).

*11 Tokyo Wonder Site is an art center that supports creator activities in a wide range of genres, interdisciplinary work, and experimental work, while also dedicating itself to the development and promotion of new art and culture from the heart of Tokyo. It was founded by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 2001 as an organization devoted to supporting the nurturing of young artists, and it operates facility spaces dedicated to providing venues for artists to exhibit their works and spend time in residence working on creative activities or research. Since 2006, it also conducts a variety of residency programs for artists and creators from Japan and abroad working in a variety of genres. In 2017, the organization’s name was changed to Tokyo Arts and Space (TOKAS).

*12 Found footage refers to the technique involved in referencing or reusing existing film/video footage in the creation of new film/video works.

*13 The Institut für Raumexperimente (Institute for Spatial Experiments) was an educational program conducted over the five years from 2009 to 2013. It was led by the artist Olafur Eliasson and operated within the Berlin University of the Arts. Although its actual arts activities have now been concluded, the base of activities has been moved online and continues to function.

https://raumexperimente.net/en/

*14 “BODY/PLAY/POLITICS” is a group exhibition composed of six contemporary artists from Europe, the U.S., Southeast Asia, and Japan. Tamura showed an installation work titled Milky Bay that took the Yukio Mishima novel The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea as a base to present a new perspective on Japan’s postwar era through the history of modern bodybuilding.

*15 Chemistry / The Story of C: The cruise ship Diamond Princess, which later became the site of a cluster of COVID-19 infection cases among its passengers and crew, had originally caught on fire while still under construction at a Nagasaki shipyard eighteen years earlier. As a result, its sister ship Sapphire Princess, which was being built at the same time, was renamed Diamond, and the original Diamond Princess was repaired and renamed Sapphire. The work revolves around a story stemming from this episode of diamonds and sapphires. It can be seen in the archive at the following site.

https://www.yokohamatriennale.jp/2020/concept/episodo/08/

*16 Reformulation of an Artistic Practice on Fragments is the title of the doctoral dissertation Tamura submitted at the end of his course in the Department of Film and New Media at Tokyo University of the Arts in 2016. In the dissertation, Tamura elaborates on the concept of “fragments” as an important part of his practice, with examples in his past work, and explains in detail the acts of “dismembering” and “connecting” them in the process of creating work of substance.

Related Tags