- Following your outdoor theater performances of Mizumachi in Adelaide, Australia in 2000 and your performances of Ryusei in Hamburg, Germany, and Belfast Northern Ireland, in 2001, this was your first Latin American tour, as well as the world premiere of your new work Natsu no Tobira.

-

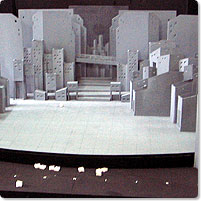

Our first group arrived in Mexico’s Guanajuato on Sept. 25 and the second group on Sept. 28. We had two different sets for the Mexican and Brazilian performances that we made completely in Japan and then shipped to the two countries. We spent about one month putting together the sets from the end of July and sent the first one to Mexico at the end of August. The group of buildings that makes up the set this time was designed by Takeshi Kuroda. He also did our last set for Keaton, giving 3-dimensional for to my idea.

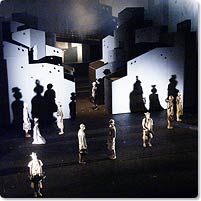

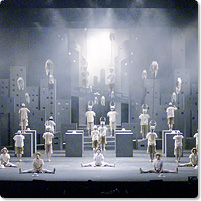

The theme this time was a “stage of light and shadow.” The audience is amazed when they suddenly see a blazing white-light stage. The origami-like buildings of the set are made of plywood. They are painted a delicately tinted gray and become white when the lights are shown on them and become virtually black when no light is shown on them. The entire set fits in four 20-ft. shipping containers. It is an awfully big set to be taking overseas. - When did you begin your rehearsals for this production in Japan before leaving?

- We started in January of this year, do three or four hours a day, six days on, one day off. We decided on the title early on with a special consideration for the fact that we would be performing in Mexico and Brazil. We seem to associate the image of summer with Latin America, don’t we? So we thought of the Japanese summer, the Mexican summer and the Brazilian summer. The consciousness of these three is certainly different. We also wanted to keep a feeling of openness to the title, so it became Natsu no Tobira, or “The Summer Door.”

- That is a title that stimulates the imagination. The play Sakashima you did once earlier at Nara’s Murou village was a play about one girl’s summer. Wasn’t it?

- The Sakashima performed in Murou, Nara is a summer in the countryside. This time it was going to be an urban summer. A story about a girl who spends her whole summer vacation watching television.

- In the story there is an incident of a phantom murder and other fragments of contemporary Japanese life. Does this represent a new change in your subject matter or writing style?

- I wanted to bring out a “shadow” aspect. Or, shall I say “virtual image” aspect? Since Ishinha is originally a group that started out acting with whitewashed bodies, there has always been a strong fictional or fabricated aspect to our plays. Since that is the case, we thought we could try doing something even more fictional or fabricated in nature. With Natsu no Tobira we used television as the connection to the real world and then used a device by which the girl’s fabrications develop from that starting point. Her younger brother is murdered by a phantom killer, as if her brother had died in an instant, she can’t really identify with the event when she sees it reported on the TV news. Like the shadows made by the summer sun, the virtual image apart from reality begins to grow bigger. For the sound, we use recordings of a television left on.

- When I saw your rehearsal in Japan the Japanese news coming from the television made an effective background noise, but in your overseas performances did you use subtitles or something?

- There are ten scenes to the play with titles like “utatane, “machikage” and “kageboshi,” and these are the only things we used title for, in the Japanese hiragana, in the Romanization of the Japanese and their translations in Spanish and Portuguese. There was one case where the Japanese title “kawatare” (which means asking someone who he/she is at twilight) was mistranslated into Spanish with the meaning “kataware — my other soul.” We corrected it, but I thought that other title was interesting, too (laughs).

- How did the physical training begin in your rehearsals?

- First of all we think about the “body.” We worked very thoroughly on the concepts like “unnatural movement,” unnatural and un-free movement when you can’t move as you want to. For example, moving the legs at a seven-beat and the arms at a three-beat. If you wait until the script is finished to begin working on that kind of movement it will be too late, so in rehearsals we work first on creating the “body” movement. The movements are things that I think of and also things that the actors think up, but with the work this time, there was a stronger element of what the playwright myself was dealing with in the part that was created in the rehearsals. I wish we had had a little more time for what you might call the “rehearsal stage ideas,” and the work of fitting the movements that came out in the rehearsals into the script of “light and shadow.”

- Part of the appeal of the Ishinha Jan-Jan Opera is the unique use of words and a unique off-beat type of step to the movement. What made you begin pursuing “unnatural movement”?

- For me, just doing dance isn’t really interesting. Of course, there may be good movement in dance, but for me it is not interesting just to follow the dictates of a body that begins to dance of itself even when you are not intending to dance. It takes a lot of will power to give up that inclination to dance, and it even takes a deliberate development of technique. It is something you can’t do unless you put it together first in your mind. For a baby to eat, it is easiest just to pick up the food with its hands, but we teach the child to use chopsticks to pick up the food. It is the same kind of movement that requires a conscious effort for the body to learn.

- Are you saying that what Ishinha requires is not dance as designated form but movement as undesignated form?

- There are numerous people with different bodies in Ishinha. We don’t do things that require the kinds of bodies that fit dance style, we have to do things that fit the weight that each of our members carry in the form of their individual bodies. In some small theater works, they often bring in things like a jazz dance sequence, but I don’t like to see actors who don’t have that kind of body trying to do that jazz dance sequence anyway. I think there is movement that fits the people who are actually up there on the stage. We don’t use a choreographer, we have each person think of their own movement. That is Ishinha.

- Would you tell us something about the performances in Mexico and Brazil? Rather than your usual outdoor stages, both of these performances were done in theaters, and we hear that you had some trouble getting the right equipment?

- There was especially a lack of the lighting equipment we needed. The theater didn’t have enough lights to do the complete white-out of the stage that the first scene calls for, and we weren’t able to borrow enough additional lights either. There may be different ideas of what “brightness” is in different countries. For example, in Germany we had breakfast by candlelight (laughs)! Also the technical skills available to the theater staff at the theaters this time was not up to the level of those in Japan or Europe. There is also what may be a regional concept of “This will be good enough.”

- The city of Guanajuato where you performed in Mexico is at a high elevation of 2,000 meters, and we heard that several of your actors collapsed during rehearsals and had to be hospitalized.

- We knew that it was going to be high altitude and originally we planned not to do any serious rehearsals there. Also, because of all the trouble we were having getting the stage equipment together, there wasn’t time to rehearse anyway. But when we finally did have to try out the movements in rehearsal, we had people collapsing. So, for the Mexican performance we shortened the rigorous movement parts and we had our music person, Mr. Uchihashi, rewrite the music parts on the spot to create longer music sections to cover for the shortened movement parts. By the way, Uchihashi’s “Daxophone” in the music parts was a big hit. There are only four of these instruments in the whole world, and when he played it the audiences loved it.

- How does Uchihashi create the music?

- The music is the last part that gets decided on. During the rehearsal, we work out the movements just using a rhythm machine. In the end, we talk with Mr. Uchihashi about our images and then he works out the music. Conversely, we can’t work out the movement until the stage art is in place, so the first thing we do is to make a model of the proposed stage set and move it around while we think about what we want. Actually, it is the movement that we start to work on first in our rehearsals, and in this case we got the art plan together for the stage around May. I think we changed the art plan about three times. Mr. Kuroda is an artist who collects scrap metal, lets it rust and then uses it to create works that look like they are from outer space. He sees a lot of theater and understands it, so he is very good at creating stage art, I feel. In fact, the lighting is very important and I would always light to get the lighting plan together as early as possible, but eventually, like the music, it becomes one of the last things to be finalized. During the planning stage it is often the case that the opinions of the art person and the lighting person don’t jive well. So. I try to get lighting equipment in place at the rehearsal studio from an early stage so that we can experiment with it.

- Your performances were well received in both Mexico and Brazil, and we heard that you got standing ovations each night.

- When we did one of our works in an indoor theater at Tokyo’s New National Theater ( Nocturne , 2003), I didn’t really feel that we had done a completely successful job. But this time, despite the equipment problems we had and the less than perfect conditions, I think we had a clear aim in our “light and shadow” concept and we knew what points we wanted to achieve to make it work. I believe that is why it communicated well to the audiences. We made “shadow” the protagonist, and when we brought shadow to a climax with an eclipse of the Moon, the audience really appreciated the effect. Even though the prices of the tickets were quite high for young people in Mexico and Brazil, both were well received.

- We hear that you did a workshop in Brazil as well.

- Yes, but just for one day. The participants had watched some videos of Ishinha performances before we arrived. And it seems that the Brazilian theater scene is quite avant-garde, so we wanted to make it a workshop that they could enjoy doing. We tried to do a Jan-Jan Opera as a sort of Japanese-Portuguese jam session. We would say ohayo (good morning) in Japanese and have them answer “good morning” in Portuguese. It seems that there is not much formality in normal spoken Portuguese, so it was fun. We had them do some of the Ishinha steps and we were planning to finish the workshop up after about two hours, but they asked us to keep going for another hour after that. I felt that through the workshop, the Brazilians were trying to find out how Ishinha goes about creating a stage work Anyway, they were very interested and it was evident that really wanted to actually do the movements and everything we had to show them.

- For us in Japan, Ishinha has an established image and reputation for your “outdoor theater” but when you go abroad does it have to become indoor theater?

- If we had the extravagance of the amount of time it takes to do an outdoor work, I would certainly like to do it. But, in the end it is difficult enough just doing a production indoors in an existing theater. It may be that doing an outdoor work would heighten the tension for overseas audiences as well and make it worthwhile. Doing a performance in a theater gives the false impression that it can be done just as well in a theater, so if the conditions where made possible, I would definitely like to do outdoor productions overseas. But, those necessary “conditions” would be really tough to come up with. In fact, in 2008 there will be a “Celebration of the 100th Anniversary of Japanese Immigration to Brazil” in Santos and we have been asked if we would like to do an outdoor work at the Santo harbor. They want us to create a play about immigrants. Santos is the first place that Japanese immigrants landed in Brazil.

- We hope you will definitely take that opportunity.

- That would probably be the death of me (laughs). I didn’t have much time to walk around Santos, but what I could see from the bus was enough to bring tears to my eyes. There are ruins of the sections of town where the Japanese immigrants lived, probably a 19th century town. It was an emotional experience for me. That area is a slum now and a lot of the people there are probably illegal squatters, but you could feel some of its history, as if time had stopped. It was a powerful and moving thing for me. Some of the local staff who worked with Ishinha this time were of Japanese descent and have Japanese faces, but their hearts are purely Brazilian. The Japanese immigrants still have Japanese faces by inside they are purely Brazilian. There may be some kind of theory of the body and mind that could be explored here, but it is also a sad thing. The immigrant to Brazil have tried to save some of their Japanese culture by teaching their children Japanese, but by the third generation there is no way they can have any longing for the homeland left in them. And, while they are good at speaking Japanese, it is not the standard Japanese and it is hard to say what kind of Japanese it is. It is not their language either. I believe that language is culture, so their “unidentifiable Japanese” has a big reality gap to it.

-

But Santos is a town that can serve as a background and it is a town with a Japanese language and people of Japanese descent that will not be found anywhere else. It should offer the opportunity for a completely new development of Jan-Jan Opera. With all this going for it, don’t you think that Santos has got to be the site for your new outdoor theater work?

Yukichi Matsumoto Interview — Part2

-

This interview from 1998 was first published in the book Ishinha Taizen. It is being reissued here with the permission of the Ishinha theater company in translation for overseas transmission.

- From the time of the Nihon Ishinha, the predecessor of your current company, you were already making special efforts to stage outdoor theater productions. What does outdoor production mean to you personally?

-

In the past, I have said a lot of things on this subject, but recently I have come to feel strongly that the most important meaning of “outdoor theater” is its character as a form of ”one-time theater production” in a “one-time theater.” It is not something that can be done without a strong will, determination and solid planning. It can’t be done in a haphazard or irresponsible way.

In the case of indoor theater, you reserve a time slot with the theater for a production one or two years in advance. But that is not something that requires any special energy to do, and in the end you reserve it as a matter of scheduling adjustment. In the case of an outdoor production you have to maintain a constant output of energy from a year before the event. If the involved can’t keep up that energy and someone says they want to quit, the whole thing falls apart at that point.

In other words it is a matter of full concentration on the project without thinking about what you’ll be doing the next year. So, if I am not thinking anew each year what makes us do outdoor production it loses its meaning. Because, to begin with, there is nothing forcing us to go to the trouble of doing an outdoor production. - The scale of Ishinha keeps getting bigger, and there must be a proportionate amount of extra effort and difficulties involved.

- Although we are doing the productions in an outdoor format, we are striving to bring more of an entertainment aspect to our productions lately, so we are playing down any shallow-level avant-garde or underground aspects. In simple terms, we are setting things up so that the audience can see the plays more fully from their seats and we are doing the ticketing and seating responsibly. We are making sure about how the tickets are sold and that each production has scenes that the audience will appreciate…even if the play as a whole may be lacking in content (laughs). This is because we believe that basically we have to do right by our audience. And I believe that there is an audience that looks forward to our once a year outdoor productions.

- Is this outdoor format something that is inseparable from your methodology as a theater artist? Are you going to be doing outdoor productions forever?

-

I haven’t been thinking about that, and it would start to get heavy if I did (laughs). In the sense of being a social outlaw…well, I think that the people writing the works are in fact outlaws, but my personal belief is that you should not be bound to any fixed ideas of outlaw type style or methodology. Outdoor is not simply a matter of building a theater outdoors, it is a matter of “continuing to stand outside.” It’s because you don’t want to be drawn into the establishment, you want to continue to be on the periphery, on the borders or margins. You want to continue to be drifting free.

There may also be ways of being even more outlaw-ish than doing outdoor. Because this is a period when we still want to be outlaws saying to the “inlaws,” “Look, we were right and you were wrong.” To be able to say, look how big an audience we can draw outdoors, or look how big a production we can do. Just because we are on the periphery doesn’t mean we have to be doing marginal scale things. We want to be the center of attention and do things on a mainstream scale too. It’s just that the place where we take our stance is different. - Looking at Ishinha’s outdoor theaters from an architectural standpoint, it seems that you can do some extremely unique things architecturally that have the capability to shake some foundations in the architectural world.

-

Since we are building structures that will not remain standing afterwards, what we are building cannot really be called architecture. It is a one-time temporary structure that is site-specific. When architects and architecture students come to see our structures they are jealous. What is good about it is that it is very architectural in a design sense but not architectural in a structural sense. Basically, a theater is a place where you create the border between seeing and being seen, so some people think that you can draw lines on the ground and say, “The stage is from here to here,” like the cure-all potion sellers who used to set themselves up on the street and hawk their wears.

If you make a theater using paper-faced shoji panels, it is the kind of boundary where you can lick the tip of your finger to open a peeping hole in the shoji. That is the kind of idea that comes out most often. When we did the play Ashi no ura kara meioh made at Yodogawa in Osaka, we dug a trough around the stage area and filled it with water as a boundary. In the end, I think a theater is probably a place where you create a door to what you might call the darkness that we fail to see in our daily life, or an “other world,” and you show that door, that boundary, as a kind of tool.

But in our case, we make the whole thing ourselves in a hand-made process that even includes making the audience seats, so it becomes a theater that creates not 2-dimensional viewer perspective on the stage like a movie screen but 3-dimensional perspective that allows glimpses here and there of the darkness or the “other world.” Since it is a temporary outdoor theater, it is different from a theater within concrete walls in that there are gaps where breezes can come in and places where you can sense other presences. But, it also adds another difficult aspect in that we have to deal with the problem of attracting the audiences’ interest in this “theater structure as expression.” - Among the key words that keep appearing in Ishinha works are roji (alley) and haikyo (ruins).

-

Roji (alley) and haikyo (ruins) are “kaze no sumika” (places where winds reside).

The philosopher Takaaki Yoshimoto made an interesting observation. People who line up their potted bonsai trees in your own backyard are setting them where they can be seen by themselves from their own porch, but people line up their bonsai along the alley are putting them out where they will be seen by passersby like the stand of a noodle peddler who sets up on the street at night. And if they set them out on the alley like that, they can’t really complain if a passerby walks off with one? An alley is that kind of place. It is both a road and an extension of the people’s yards. It is a place where the boundary between you and other people is ambiguous and where the sense of propriety is lax. But human beings also have a characteristic tendency to need to always distinguish in their lives between what is one’s own and what is the other’s. But for irresponsible and sloppy people like us, this kind of world of lazy ambiguity can be very refreshing and welcome. I think what defines the alley is the relief in knowing that “They’re that way too. I’m not the only one.”

A “Home” is something where there is a creator and an owner, but alley and ruins have neither creators nor owners. There is an apartment complex in the Shimotera-cho district of Naniwa-ku, Osaka that is like ruins, like the old Kowloon apartment buildings of Hong Kong. When you look at it you can imagine a 3-dimensional form of “alley.” They say that originally it was a stylish complex designed by a French designer, but the residents let it go to pot. It seems that a lot of difficult tenants lived there. That was in the Taisho Era, so it is not like it was full of today’s proper salaried workers, and the result was that they undermined the original intentions of the designer. I guess that instinctually they just weren’t able to abide with the apartment concept, where everyone has the same uniform living space.

You don’t find many ruins left in Osaka today, but it seems to me that it would be healthier if there were ruins like old wells here and there around the town. Places where the bad can be bad, places where birds can build nests, places like scars in the cityscape … A city without scars is not a very interesting place. - The musician Yukio Fujimoto says that what impressed him so much about the Ishinha stages is that although they may seem earthy in spirit, in fact they are composed with a high degree of modern simplicity and functional beauty.

- The director Shogo Ota said that Ishinha is misunderstood because they call their works “outdoor theater,” which brings with it images of fields, earth and nature, so perhaps they should think of using another term. Just because we are doing outdoor theater doesn’t mean we are nature children, and in fact what we are doing is very man-made. We like artificial lighting, tin roofs and thin overlays. We also like the world of plastic and miniatures. In that sense we might be quite modern. I personally consider myself ultramodern (laughs).

- In the Ishinha staff you have people from the movie world like the art director Hiroshi Hayashida and the stage director Kazushi Ota, don’t you?

- People whose training is in theater tend to think in terms simplification or symbolist methodology. They say for example, “You can’t use water on a stage, so let’s use paper,” and they think in terms of abstraction. That becomes their theory. “Theater” itself is an abstract thing. The film people I know what you might call a more masculine way of creating things. They tend to want to use the real thing, and they dislike things that are artificial or synthetic. So they choose the real thing whenever they can. Even though movies are an art form where reality is converted into images on film, they are more inclined to insist on the real thing. When we are working to create outdoor productions, that kind of approach used by movie people often provides us with good examples.

- Are there any specific movie directors who have influenced you or whom you like?

-

There are interesting films that come along from time to time, like Blade Runner and Baghdad Cafe and Bad Blood (Mauvais Sang) , and the Japanese director Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories and the list goes on and on.

And, when it’s a Fellini or Bertolucci film I can’t resist watching to the end. Among the Japanese directors I like Kaneto Shindo. I think his Hadaka no Shima is masterpiece. I like the gritty humaneness of it. There is also the movie Hadaka no Jukyu-sai based on the story of the 19-year old Norio Nagayama who was given the death sentence. I like movies that follow the traditional theories. I love Kurosawa. He was a true artist, very skillful at layouts, maybe even more so than Picasso, I think. He was very good at drawing, and he planned and filmed his shots very carefully. For example, if an actor is standing here in one shot, he has to be over here in the next shot. - In terms of literature, it seems that more than any other company Ishinha has developed on the adventurous use of words that Kenji Miyazawa pioneered. Do you feel a special affinity for Kenji’s word play or worldview?

- I have been influenced by his forms of expression, as if there is spirit inside a lump of mineral. The fact that the lines in my scripts are often strings of metallic and material nouns may be because I learned about the mineral quality of expression from Kenji Miyazawa. I have never staged a Miyazawa play but I probably have been influences by his worldview. But for me, Kenji Miyazawa is a literary giant, so I don’t try to talk about his work like an authority.

- What is the most relevant contemporary issue for you today?

- The thing that I am most concerned about is how today’s young people have lost a sense of home. They have no hometown in their hearts. I tell the young people in our company to create a hometown in their hearts, even if they have to go out and find one deliberately. A person without a nostalgic hometown is not really a full person. That hometown doesn’t have to be one with a traditional Japanese style wooden house. It could be the South harbor section of Osaka where Ishinha does its outdoor productions, or it could be an apartment building. I tell them to find a hometown and create lots of legends around it. Because I believe you can find nostalgia almost anyplace. I think the novelist Haruki Murakami has tried to create something like the nostalgia of an apartment complex. I think everyone should find or create their own hometown.

- Can you say something about the involvement and influence of visual arts in your work?

-

In our day there were a lot of interesting people in the art scene. If you ask about my influences I would have to say the Gutai Group of Osaka, led by Kazuo Shiraga and Jiro Yoshihara. They were people who truly sought to break apart the concepts of art. They were very avant-garde but also very hot-blooded. They literally put their whole body and soul into the things they did. Because I discovered them at an impressionable age in high school, their spirit remains very strong in my memory.

In the end, expression is doing things that no one has done before, break down the things that already exist and create expression that hasn’t existed before. More important than any internal themes and such is the fact that you have to first of all finding material and method. If you find something that is interesting you have to make it your own. It isn’t a matter of the contents. If no one has done it before it is going to be interesting.

Another influence form a different period came from the group “Play,” which was what you would call a performance group. It was led by Keiichi Ikemizu. I helped out with some of the performances too, but they were a group doing interesting things. In those days it wasn’t called performance, it was called “happenings.” They did things like making a 5-meter “egg” of fiberglass and setting out to sea at Cape Usio. The egg would then ride the sea currents and end up in someplace like San Francisco. One famous work they did was to stack two or three hundred logs into a sort of pyramid structure to try to capture a thunder demon. They were doing these things as a natural extension of art, but all we heard from the people who saw it was, “Is that art?” - We hear that you like books of photographs.

-

Photographs are often more interesting than paintings. Since you actually have to go to the “place” to make a photograph, you can’t just sit in your studio and create works. The works produced in a creative process that starts and ends in the confines of the studio are not interesting to me, no matter how finished they may be. I am interested in the kinds of works that can only be made by going out and doing the on-site documenting and encountering the external world.

I think the Brazilian photographer Sebastiao Salgado’s book Workers: An Archeology of the Industrial Age with its photos of workers is very interesting. I once wrote a play based on images I developed from looking at the photography collection Inu no Kioku and Hikari to Kage of Daido Moriyama. - We hear that you were also influenced by the thought of the Surrealists.

-

When I was a college student we got into exploring the concept of the “surreal.” It was a process of creating your own personal interpretation, not the one accepted as the art term’s definition. The usual worldview is one where you have the big framework of the world at large and then a variety of elements are included in that framework, but the concept of surreal that we came up with was exactly the opposite. We thought that in fact it was a case of there being insignificant and indefinable individuals existing and the world was nothing but an uncertain concept resulting from the sum total of all those individuals. In that sense it was very Buddhist and defining a world where literally anything could happen. We thought that the true meaning of surreal was that when you accept all the separate evils and goods and try to put it together into a world, any images you have of the world would fall apart. It was an idea completely different from Dali’s image of the surreal.

So, you can never have an overview of action and no person in this world can take a stance in a place where they can look down and get an overview of it. It is inherently impossible to gain a consciousness of the world and if what we see as the world is merely the chance accumulation of its parts, the concept of the world is something that constantly rustling in the wind and no fixed image is possible. We thought that if a wind happens to blow a log at you, all you can do is to catch it. That is the place where the three points of the body, action and consciousness collide.

I think that the surrealist concept is that you start from a very individual realm and go out and fight the people you should fight and kill the people you should kill and that lead you to the world. So, the point of departure for the surreal worldview is taking care of very personal things on a daily basis.

Around that time I read something in a theater magazine that made me laugh. At the time it was popular to talk about Brecht and publish discussions between noted figures in the theater world with titles like “Can the World Be Recreated in Theater?” What kind of theater people are thinking about such things (laughs)!? Do they think they can conceptualize the world? I thought that was overdoing it, setting the sights too high. Even though that was just the viewpoint of a limited group of people, it seems that they were under the illusion that the whole theater world thought that way. And I remember think this is what makes the theater world seem so far removed.

But now, it makes me mad to see the opposite is happening, as playwrights are overly concerned with their own personal world. There are times when I want to say, “Don’t just write about yourself. Why don’t you try writing about the world sometimes (laughs)? - We hear that you are always objecting to things like environmental or anti-nuclear activism as insincere.

-

Those kinds of people always have their worldview as if some kind of “world” really exists. I was taking to the butoh artist Akaji Maro once and he said, “If they ever build a bridge to America, then I will believe that the world is one.” Can you get a feeling that the world is actually one by getting on an airplane and flying to another country? Are there people really have that feeling, have they taken a measure and tried to measure it (laughs)? If they ever build bridge that reaches all the way across the Pacific and build a road on it, then I’ll believe that the world is one. As long as we are flying around the world in airplanes, it may be only natural that there are going to be world wars and racial prejudice.

When I went to the public bath at Ryugu Hot Spring Spa at Tenpozan near the Osaka harbor, it was full of men who work on the international transport ships. They were all muscular men and you could see clearly the different regions they came from. If you go to a regular public bath in Osaka, it may be reassuring to see the usual salaried worker and shop owner types around you, but at the Ryugu Hot Spring bath those men looked tough and you could see that the faces of even young junior. high school age boys, who had probably followed their father’s profession by going to sea, were already weather-worn. It gave me a renewed appreciation for the reverse regional ethnicity in the contemporary [global] world. One might think that people’s bodies and ways of thinking are getting increasingly homogenized today, but when you look closely you find it isn’t really true. Scientifically speaking it may be getting more homogeneous, but in fact things haven’t really changed much. And even when a billion people or so are connected by the Internet, I don’t think this part will really change. - What is different about the former Nihon Ishinha theater company and the present Jan-Jan Opera Ishinha?

- Eventually the biggest difference is that before I was directing and staging with my own body as the basic medium and a sense of myself at the main actor, so everything was done while listening to my own body. Because I was thinking about everything with this body of Yukichi Matsumoto as the central axis and the company hinged around that, I was more of a single butoh dancer than a director.

- Is it safe to say that the change came around 1985 with Osiris?

- Yes. I was beginning to feel an age difference between myself and the actors and the era wasn’t as interesting as it had been before. So, it was a period when everything I was doing was trial and error, and I think it was a period just going no place. It wasn’t until entering the year 1990 that I began to feel that I could relate something to society again and it became easier for me to create works, shall I say, or the distractions were gone and I could get into works more deeply.

- What does the body mean to you?

-

I am not conscious now of my own body but the body in general. I personally have this weak body, so I have always had this image of the human body as an awkward and clumsy thing. I started out with this image of the body as a very awkward thing, like the shape you see when you take an X-ray. But when you step some distance away it starts to look better. I like that step to a distance where it looks better.

So, I never had the idea of expressing physical beauty on the stage, rather I was thinking things such as making the embarrassing and unappealing form when you are squatting over the toilet look a little better by raising it five centimeters or so. Or, I think of things like wouldn’t it be interesting if you took away the scythe from an old woman working in the rice paddy and had her walk backwards on the path between the paddies like a pantomime. What I consider our job to be is to take material like this and make it our own.

At a public bath you would see that my body is different from most of the men in the world. I used to be self-conscious about that difference between my body and everyone else’s, but now I think that I made dance out of that difference. For example if a thin person like me got into a fight they would eventually lose, so I became good at dressing to make myself look bigger than I am. There is a big difference between the bodies of people who size themselves up against the rest of the people and make efforts from the time they are kids to compete and the bodies of those who never even try at all.

A person’s body shows everything, about the way a person thinks and how he or she lives, so if you watch that person’s body for a day you learn everything. So think it is a matter of how much you have looked at people’s bodies as you grow up. The weight of our history of watching people’s bodies as we grew up is great. Watching your parents’ backs as they prepare your meal, watching your parents at work and whether you felt like you want to be more like them, or whether you reject them … - Is there a core to the Ishinha that hasn’t changed all these years?

-

We believe that we get more fun out of what you might call the chemical reactions that happen in expression. For example, the moment when a log suddenly looks like a pillar of gold, or when feces look like gold; that kind of magic.

When they had us paint long ago one of the themes was making everything look uniform. In other words, making things like soft meat and hard objects appear to be of the same quality with no distinction between things like living things and non-living things. The image that our Jan-Jan Opera is working with today is pursuing that kind of uniformity. Speaking in more universal terms, it is seeing everything as matter. A worldview where there is no difference between the organic and the inorganic.

There is uniformity is a scene where everything is wet after a rain, and also the scene of desert where everything is dry sand. If the ordinary, everyday is a world where everything seeks to make its individuality clear, we long for an extraordinary world of homogeneity where everything withdraws its expression of individuality and become uniform and equal. Meanwhile, I also long to melt into that world. This is a core thought that Ishinha has always had. - It can be said the “enlightenment” (satoru/satori) is a state where you can see everything as being equal and uniform can’t you?

- It is not stressing your difference but breaking out of your shell, shedding your colors and letting yourself be enveloped by something larger, like a speck of dust in the universe, and letting a deeper self be born from a denial of the present self. That’s what “satoru” is.