- In February of 2009, the New York based musician and photographer Aki Onda had his first Japan concert in three years. At that time, you suddenly joined in the session with Onda and khoomei vocalist and performer Fuyuki Yamakawa, and I was impressed by the way you used a variety of different methods to create sound between the stage and the audience, as if you were directing the live session itself. Before you launched the Tokyo Grand Guignol theater company, you were in charge of music for the Jokyo Gekijo company, and you also worked with a number of musicians in the 1990s. So, it clearly appears that sound (music) is a very important part of your artistic expression. Could we ask you to begin by talking about thoughts on music and your approach to sound itself, and what kinds of music you normally listen to?

- I don’t listen to music much at all. I don’t listen to CDs at all. I don’t even have a CD player. When I listen to music it is only on YouTube. Sometimes I create the sound for my performances on YouTube as well. For example, I created the sound for the HARAJUKU PERFORMANCE PLUS SPECIAL performance I did with Yamakawa on YouTube. The concept was a “cover band” (a band that performs covers of other people’s songs), so I picked out a number of pieces on YouTube and sent the links by email to Yamakawa and said, “Will you sing these for me?” [laughs] And I sent the YouTube address for a video clip of Nico singing with Velvet Underground to the home of the boy (Takumi Lavernhe) who performed with us and a message to his mother to have her son memorize the song. That is the way I work often today.

- How did you meet Fuyuki Yamakawa?

- I often take walks, and one day when I was walking on the street in Shin-Okubo, there came Yamakawa and Onda walking down the same street toward me. I think that was the first time I ever really talked to him. Before that I had gone to see Yamakawa’s exhibit “The Voice Over” and maybe exchanged a few words of greeting, but that was all. For our “HARAJUKU” collaboration, the offer came originally from the producer Yasuo Ozawa (Representative of the Japan Performance/Art Institute), who said he wanted the two of us to do something together.

- For the HARAJUKU performance, Yamakawa, you, actor Kyusaku Shimada and young Lavernhe formed a band. The performance was somewhere between theater and music. It was a very unique band, with Yamakawa’s amplified heartbeat and khoomei style vocals, you doing drums while drawing blood from your body and Lavernhe reading recitations.

- It began with just the pun of an idea to wear UNDERCOVER clothing and perform as a cover band, and as for the question of what music we should cover, the video of Iggy Pop performing that was playing at the UNDERCOVER shop looked good, so I thought Iggy Pop and others of that time might be a good choice. But when we got into the actual preparation with Yamakawa we got the feeling that there would be something lacking if there was just the two of us. Starting out in that way, we looked at what we had and thought about improving the balance, which led to the idea that it would be good if there was a child who could join us, and that led to our inviting Takumi Lavernhe to join in. That made us three, but there was still a feeling that the balance wasn’t right, so just about four days before the performances were to start we asked Shimada to join us.

- The act of taking blood from your body as you perform is something that you have done in the past as well. What led to that idea?

- People have asked me that before, but I don’t really know the answer. It is not something calculated. I just get an image like that suddenly and once I get the image I want to act on it. I am not the type of person who does crazy things, so I do the research and I decide that drawing off a total of about 500 cc of blood in the two days of performances would be all right. Also, if you don’t do it properly there is the danger of the blood clotting, so I studied the proper process involved in drawing blood.

- Does extracting blood from your system bring any perceptual or physical changes that you can feel?

- In the case of the HARAJUKU performances there were two performances on successive days, and on the second day I did start to feel faint. But since I am only extracting a safe amount, it wouldn’t cause any perceptual problems if it were just one performance. In the past I did a performance where I got a transfusion of blood that had been taken from someone else beforehand. In that case there is always the very slim chance that my body will have a rejection reaction to the blood. During the moments before the reaction does or does not occur there is an element of fear, but once that is past and I’m sure that my body has accepted the donor’s blood, I don’t feel anything. But, when you think about it, that “feeling nothing” is even stranger to me. The fact that you don’t feel anything after a transfusion of blood that was flowing in someone else’s veins until a while ago means that your body has already begun using it. That blood is flowing into the brain and transporting oxygen around your body. The realization that having someone else’s blood circulating through your body occurs so uneventfully makes me surprised and gives me a strange feeling.

- In other words, it is interesting to realize that you don’t even notice that you are having your blood taken or that someone else’s blood is flowing in your veins, as long as there is no reaction?

- That is part of it, and there is also the fact that when you draw out the blood, this vital fluid that was functioning in your body until that moment is now outside your body and comes to be no longer part of yourself but something that is seen as completely different. That is a strange phenomenon and interesting because of this double meaning. And there is also the realization that, because you are taking the blood within safe limits, this is all the blood that you can draw at one time. If it is from a wound you can lose much more and make a big show of blood, but if you are staying within the limits of safety, this small amount is all you can take. This realization of how small an amount you can actually take safely is another interesting fact.

- Did the “Vanishing Points” exhibition that you held at the gallery P-House in Roppongi, Tokyo also begin in the same way from a single image that came to you?

- That was also a case where the image suddenly came to me about a month before the exhibit. It was a time in my life when I had been living a rather reclusive life in Tsukuba and rarely having contact with people. The place where I had been living for about three years was rather secluded with few houses around. When I came back to Tokyo I was intending to do something [in the art world] but I hadn’t decided what exactly I would do. I am basically one who prefers to have other people decide things for me, and I thought that if I just hung around for a while someone would decide things. The first one to come to me with an offer was Takaaki Akita of P-House. So, it was decided that I would do an exhibition. If it had been someone from the theater world who had made me an offer first I would probably have begun doing theater first.

About a month before the exhibition was scheduled to open, I woke up one morning and was washing my face when I had the thought, “I should put myself in a box for this [exhibition].” I have no idea why I thought that. Perhaps it was based on the fact that I had once been interested in mummy (Buddhist monks who confine themselves to a hole in the ground or cave before death and end their lives in a state of meditation and the body goes on to become naturally mummified) and done some study about it. But at the time this exhibition idea came to me I had long forgotten about mummy. - In fact, you put yourself in a box with a minimum ration of food and water and the box was displayed with yourself inside at the gallery. No one who came to the exhibition could see you inside the box but they could knock on it and call to you inside. Can you tell us what you experienced in that box, at least to the degree that you are able or willing to? It was certainly completely dark inside, wasn’t it?

- Yes, complete darkness. In order to keep my caloric consumption to a minimum, I just lay down most of the time. I was awake but lying down all the time. There was no particular reason for the 24-day length of the stay in the box, other than the fact that 24 days was the period the organizers had given me for my exhibition. In the early stages there was a strong sense of fear involved and around the 12th day it was quite difficult being confined in the box like that. But since there was also a feeling that I had reached the halfway point, it became easier after that I just spent my time counting the days and thinking about a variety of things. I limited energy intake to about 128 kilocalories a day, which is pretty close to the limit when you consider base metabolism. As a result, my bowel movements and such stopped very soon after entering the box.

With the body being thrown into this extraordinary condition, there were times when I felt that I might go over the edge and die. It was as if I was suddenly confronted with the extreme decision of, “What should I do? Can I just let myself die like this?” I don’t think this is a decision that can be made purely in the head, but the feeling that I was facing that decision came, and I believe it was on the 12th day or so. It felt like a temptation to just let myself die that way. But I was still able to think rationally, so I was able to stop myself. I thought it would be a terrible imposition on everyone involved [if I died], or that there would be people I would anger by letting myself die that way.

By the time I had passed the halfway point, however, I had made the decision to keep living, and I found myself deciding that I wanted to have children, which showed that I was beginning to use the circuits of thought of someone who intended to live normally.

The doctor I consulted had told me that I might be in trouble if I didn’t consume more a liter of water a day, but I found myself only desiring to drink about 250 cc a day, and I had no problem living on that amount. I wasn’t forcing myself to limit it to that amount, and I was prepared to drink much more if I needed to. I just didn’t feel a desire to drink more. My body was in a self-protective mode and I felt as if my body had become transparent. Also, in the complete darkness I lost the sense of time. - In complete darkness you also lose any sense of color, don’t you?

- Black is a concept in the head, and I found that it is eventually a relative concept, because after I had been in the box for a while I lost the sense of black as a color. What was it I felt? Can I say that in contrast I sensed the generation of a very white light? There was no difference anymore between the generation of light and darkness, to the point that I no longer could tell one from the other at all.

From some point in the 24 days I began to be extremely aware of the sound of cicadas singing. It was summer at the time and every time the gallery door opened and someone came in, there would be a rush of the sound of cicadas coming in too. I believe it must have been partly due to the extreme state my body was in, but all the sounds felt as if they were assaulting my body and the sound of the cicadas in particular was so overwhelming that I almost couldn’t tell what was happening. The call of the cicada is actually the mating call of the male. And, although this may be after-the-fact reasoning, it can be said that the busy commercial area of Roppongi in Tokyo where the gallery is located, is a place where the natural environment is almost completely destroyed and must therefore be a very severe environment for the cicadas to live in. Nonetheless, the mating call means that the cicadas are still trying to leave a next generation, doesn’t it? And, doesn’t the desire to leave offspring imply the judgment that it is a place worth living in? That realization truly left a strong impression on me, and I feel that it changed something in me.

Gradually I also began to have something like a sense when people were around in the daytime and the feeling that they were there for me. But at first, when people would knock on the box it was annoying and a real bother for me. After I went through that change, however, I was able to appreciate it as a form of contact and be happy to receive it. - Reading your blog at the time, you said that you didn’t want people to see your “Vanishing Points” performance as god-like act on the order of a mummification. You said that at the end you wanted to surprise everyone by coming out of the box happy and healthy.

- That’s right. I had taken some medicinal alcohol in with me from the beginning for the purpose of wiping my body clean, and before I came out I was very careful to clean myself well. And when it was about time to come out, I found that my hand was forming the shape that a sushi chef uses to make sushi. So, I thought to myself that I must want to eat sushi when I get out [laughs]. Before that, as I was nearing the end of the stay in the box, I had been doing some image training of myself going to eat Peking duck when I got out.

- It seems to me that, thematically, the act of displaying yourself shut up in a box involves the question of human communication.

- Yes. The things I do always have things going on at a number of different levels. For example, although it is an act of exhibition, the viewers can’t see me from outside the box, can they? Although it is written that I am inside the box, that is only information communicated by words that may in fact be a lie, and in fact there were many people that did think it was a lie. And there were surely people who wanted to believe that at night I would come out if I wanted to. Even if there was a list there of the things I had taken in the box with me, there was no way that people could verify if it was in fact true. For that reason, you could say that it was also an exhibition dealing with the question of “reality.”

As another example, there was a time when I exhibited some HIV infected blood with a notice saying “This virus cannot be transmitted by airborne infection.” The sample exhibited actually did contain the blood of an HIV-infected patient, but because it was simply written that way on the display card, viewers didn’t know if it was actually true or not. But when people read something like that it can induce a high level of fear, whereas if there were no notice they would think of it as nothing more than a fluid that looked very much like blood. It may be the same when a friend or family or co-worker makes some kind of a confession to you. But at a time like that, the judgment as to whether it is true or not is not made purely on the basis of those words but also peripheral nonverbal elements you sense may also make you feel that it is probably a lie. That is why I don’t want to do the kind of exhibition that states a concept.

In the case of the “Vanishing Points” exhibition, the only evidence that I was actually in the box would be the occasional shuffling sounds I made, so people might easily imagine someone or something was used to make shuffling sounds. And, in fact, that kind of device is often used in theater. There are devices to make people think that there is a person there, or that a person has died or that this person is in fact a ghost. So, I do a lot of thinking about the various ways that “reality” can be communicated, such as through the use of tricks and devices, or through the use of film or video, or by actually having a person present, or through the combination of words and having an actual person present. - Although your exhibit consisted of nothing more than yourself being confined to a box for the duration of the show, that fact alone functions symbolically to invoke thought in us about communication, life and death, what contemporary art is doing today and the state of contemporary society. It is very difficult to explain such a performance in words, I’m sure. And since your theater works and live performances are both of the kind that enable the audience to connect directly to your sensitivities and form of expression. In that sense I feel that it is almost futile to attempt to explain or interpret them in words.

- Since saying that they can’t be explained in words is also a form of escape, I don’t like to make or hear statements like, “There are no words for it.” The efforts to put things in words is also important, and it is important to talk about the work, but when I do something [as a work] it is always basically very complex and I am trying to present things on multiple levels of meaning. So, yes, it becomes very difficult to explain in words.

That feeling of things happening on multiple levels is also connected to my love of music and, for example, in music it is virtually impossible to have a state where only one note is sounding. It is always an interaction of multiple sounds. There is a saying in Japanese that the political genius Shotokutaishi could listen to and comprehend things being said by several different people it the same time. And that is how we all listen to music, don’t we? We are listening to the bass, the guitar, the drums and the vocals all at the same time. And if it is a song, there are words too. The fact that we are listening to all these elements together means that we are also listening to them separately. That’s why we are able to say things like, “This bass part is pretty good.” That is the kind of multiple-layered work I want to do, but if you ask me how I balance the parts at any given moment [in the performance] I wouldn’t be able to explain it at all. If you asked me why I lowered the volume on the bass track a bit during mixing, I might give a reason as an afterthought. That’s the way things are, isn’t it? And it is a bit off track to just say it is a sense. - In the stages you actually direct, there is a mood that seems to suggest that the process of composing and the process of performing are happening at the same time. It seems that you are mixing the elements in real time during your live performances and the result is like visual live performance or, in music terminology, it is like dubbing or live electronics.

- I think it is probably easier to watch that way, but there are also some people who can’t see things that way, aren’t there? When there are words the meaning takes precedence and things tend to lean in that direction. There are people who want to interpret things as they watch, and for those people I believe my performances are rather difficult to deal with.

- When did you begin making music?

- I don’t have any presumption that I am making music. And, at this age I am not trying to be humble about this but I really feel very strongly that I am a person who can’t to anything myself. That is why I have the greatest respect for people who are actually doing music well, and I envy them. It is the same with actors. When I see someone who can act well, I admire them. So I think it is presumptuous to say that I am doing music. But, I am already on in years, so I make a point not to think about that much and resolve myself to the fact that nothing worthwhile will come of me trying to decide things myself. So, I always let other people decide for me [laughs]. Having other people decide for me may sound irresponsible, but don’t you sometimes see artistic expression as an ugly business in one sense? You create something and then try to convince people that it has value and then make money off of it. I for one could never say that I wanted people to pay to hear music I made. So, I prefer to have people say to me, “You do this for us” or “That’s good enough, so please do it for us.”

- So you could never do a solo live performance of music? [laughs]

- That would never happen! The acting profession can also be seen as a bit of an ugly profession in the same way. A person really has to be big-headed to think they can take an image and embody it in a way that moves people and then make them pay you for it [laughs]. And, in that sense, the people who come to be called stars are really in a class by themselves, I believe. They are actually able to go up there and say, “Look at me!” I am not being critical at all but, for example, at his live performances, Benzie (Kenichi Asai) has the presence go out on stage and just say, “Hello, babyyy!” He is a star because he can do that. I think it’s incredible. In contrast, I am always apologizing for what I do on stage. That is a big difference [laughs]. When I think about that, I realize that the judgment of whether something has value as art always has to be made by the audience [and not yourself]. That’s why I will continue to perform as long as people are telling me to do it, but when they stop asking me to perform I will probably go off and just start doing some ordinary work to earn my daily bread. I have a strong feeling that whether I perform or not is a decision that other people should make, not me.

- Rather than your approach as an artist, that must be your approach to life, isn’t it? Is that view of life influenced by your experiences from running a pet shop and being with animals so much?

- Ever since I was small I have loved being with animals, and I grew up in an environment where I always had animals around me. So, I think that has indeed been an influence. And when you are always around animals, you see a lot of life and death. You see life and death, you see sexual arousal and mating and the laying of eggs. That is especially prominent with fish and insects. Watching them you see that it is natural for a large number of their offspring to die, and that this fact is the premise of their life cycle, isn’t it? From the time I was young I came to see death as a natural phenomenon, and before I ever had a first love I had seen crickets mating countless times. So, when I reached puberty I was able to say, “So this is what being in heat is like?” [laughs] So, in that sense you could say that I have never really known real love.

- So, would you say that you have a habit of looking down from a bird’s eye view on the big picture?

- I always do look at the big picture. I think that is how I maintain my natural balance, but that doesn’t mean that I have a nihilistic outlook. I don’t look down on things and get that feeling that they are meaningless because they are only small parts of the big picture. Half of me does get directly involved in things. It is the same with eating. I do have the desire to eat and there are times when I want to eat delicious things, but that is always just half of the feeling, while the other half of me is thinking about the process of eating, digesting and the food eventually coming out as feces. Even when I am on a date with someone I like, I am still tremendously interested in what is going on in her stomach. I never get completely away from thinking things like, “That hamburger she ate ten minutes ago is now in her stomach. What is it like in there?” Or, “Where is the actual location of the stomach in her body?” So, half of me can’t fall completely in love, you might say, and there is nothing I can do about it.

- So, do you get the feeling that other people’s loves are quite exaggerated in terms of their emotional/spiritual intensity?

- Yes, I do tend to see it that way. But, at the same time, I do understand, so it never looks meaningless or foolish to me. I have the feeling that that is the way it is with human beings. But, on the other hand, I also know that bugs don’t get that way [laughs]. When you become absorbed in only that [love] the meaning and value gets bloated and I always feel that is presumptuous and excessive.

Perhaps it is easiest to understand if you consider the case of your own child dying. Of course, I would cry and be extremely sad and in that aspect there is nothing nihilistic, but on the other hand I know that in the big picture the life of one child in this world could not have such tremendous value. If a life were worth than much, I would feel terrible about eating fish roe with my rice in the morning. Plants and animals live not as individuals but within the relationship of their species, and the natural premise in that case is that there will be a large number of deaths, and the death of an individual in the species population is not a great matter. My need to realize that is the stronger of the two. In relation to this, human beings are a species that attributes meaning to things that have no real meaning at all and live with strong emotions in their hearts. - But along with your close-to-nature way of thinking you also have a knack for using the latest technologies as well. Hearing about how you use YouTube earlier, it suggests that you are a real child of the contemporary world as well.

- Yes, I like new things like that. The “Kao ni Miso” (Miso in the face) performance (20 people of different nationalities, professions and ages muttered “kao ni miso” as they did performances) that I did for the Azumabashi Dance Crossing is something that I call “Twitter Theater” in my mind[laughs].

- While that intuitive approach in performance has been successful, what are your thoughts about stage/theater expression, where audiences expect more in the way of meaning?

- When I am creating a new work my mind sometimes thinks that way. “If I use this and this I think I can portray what I want,” or, “This should be able to communicate it in this way.” But when you go to that extreme things get boring, so I make concerted efforts to avoid working in that way. If you have so clear an idea of, “This is what I want to say,” there is no need to do it from the beginning, and if you don’t approach creation through a different circuit, it becomes demonstrative and will only solicit a response of, “Well, is that so.” On my walks I take pictures of things that catch my interest with my cell phone, and there is almost never a tangible explanation for why I have felt it was good. But, I am certain that I can believe in my instincts when I find something good or interesting at that given moment. That is the thought/working circuit I want to place my trust in and use in my creative activities.

- In your works, you take those perceptions and sensitivities you have and give form and expression to them through collaboration with other performers, and I am interested to know what that process is like. For example, with 4.48 Psychosis you reversed the roles of the stage and audience area to perform in the audience seating area. In the lobby you had a pool of blood with a motorcycle half sunk in it and between the stage and the audience area you had another pond of red blood. The sound technician was the engineer ZAK, who is active in many music activities, and the performers, including Yamakawa, were mostly people with no previous acting experience. How do you communicate your images to the people you are creating the work with?

- I don’t communicate anything. For example, in the latest work Psychosis there is a woman who reads weather reports, but she was just someone who emailed me when we were about halfway through our rehearsal period and said that she just wanted very much to take part. And there was an office worker type talking on the phone in the phone booth sunk in the pond and he was just someone who emailed me saying that he had quit his company in September and wondered if he could come and hang out at our rehearsal studio, so I used him too. Of course if these people hadn’t come of their own initiative, the production wouldn’t have included those parts, and there was no initial image that they were working from or anything that I communicated to them about the images that I might have had. People often talk about “Ameya images” but there are no such things. Those parts just happened because those people came of their own will, and if different people had come things would have been different still. That is always where the answers come from and I never have thoughts about what my own images might be.

- So, what was the working process that produced Psychosis ?

- I was told by the production manager from what day they had the rehearsal studio reserved for us, so I went there alone the first day and read the script, because I thought it would be a waste if the studio wasn’t being used. But I am really one who can’t read a script in print. It puts me to sleep right away and I can’t remember at all what I have read. But after reading to some extent I began calling people who said they wanted to take part or people who I thought might want to take part until I gradually got together a group of performers, and I had them read it to me.

- You have the actors do a reading first and then you see how it looks and begin working from there?

- When I see one part the next parts begin to come to me naturally. There is no working plan. As for the woman who read the weather report, since she said she wanted to take part, I wanted to do my best to use her in some way and I began by having her read parts from the script. But no matter what lines she read it wasn’t good. I knew that it was no good, because I have my own sort of line for decision-making. But Yamakawa looked at her and said that she looked like an announcer, so I had her read a weather report and she did it very well. So I said, “OK, that’s your part.” That is the way things get decided. During the first month in the rehearsal studio we were trying things and seeing how Psychosis could be developed.

- So, you begin with the searching process and continue to make adjustments right up to the start of performances?

- Yes. I make a lot of adjustments right up to the last minute, and we don’t know how many parts will turn out until the very end. So if we had had a half a year in the studio it would have changed even more, and if there were more time than that it would have changed even further. The project is decided by the production people and in this latest case we had two to three months to prepare, so each day during that allotted time we continued thinking and when we had new realizations we would add something here and there. That was the working process. A good example of that process involved the footnotes in the script like “Silence,” and I realized part way through the rehearsals that it was better when the footnote was read along with the script. Since we had three months to do that kind of development, we ended up with a final product that had three months worth of those kinds of additions and developments. And generally speaking, the whole thing doesn’t come together in my mind until just before opening night.

- In other words, if you are given a year to work on a production and there were three performances during that year, each of them would turn out to be a completely different production?

- Yes, they would naturally become different works. For example, if you move to a new town, the way the different parts of the town will look to you will change from the first week to the first month and then the third month, won’t they? Getting to know the town naturally takes time. If you work with a script for three months, it is like the eyes you develop after three months in a new town. And just as your perceptions and feelings change with time, the work will naturally change and develop.

- On the opening day, just after the doors opened prior to the performance, your little daughter was running around the blood pool installation in the lobby I am told. Was that also something that was decided at the last minute?

- It wasn’t my decision to have the child running. She just started running spontaneously and I was impressed how she kept going around and around it [laughs]. She just ran around it again and again.

- So that and other things like it are all OK with you? For people who saw it and those who didn’t the show probably had quite a different appearance, I would think.

- Yes. I believe that is true. I am not the one for setting a director’s seat in the audience, and I think it is a rather strange concept to begin with. Because there is only one person in the audience who will see the play from that position, isn’t there? All the rest of the audience will be seeing the play from a different angle, so it seems strange for me to be sitting there and saying, “A little more to the right. Yes, there, OK.” That is one thing about the stage that is completely different from film: it is an absolute premise that everyone will be seeing the play from a different angle. And so, theater is a medium that accepts that fact as OK.

- Were there any specific feelings that you had when you had the actors read the script of Psychosis to you?

- I am not clear as to why, but I was very conscious of the various voices for some reason. Voice is always something I am concerned with, but this time I was especially conscious of it. It was a question of the balance of the voices. The amplified sound of Yamakawa’s heartbeat was also big, and the voices of the crickets was a rather important element, so getting the right balance between them all was something that I struggled with right to the end. There was one day that the crickets were barely singing at all and I was really nervous about it. For some reason they just weren’t singing, and it became especially clear after the performance started. I said, “Hey, why aren’t they singing today?” [laughs]

- You were really using real live crickets?

- Yes. When the performance started I called one of the crew and said, “Do something! They aren’t singing!” [laughs]. I had them run backstage and get more crickets and add them to the cage. You really never know what is going to happen until the curtain goes up. Eventually we had to leave the cricket part up to the crickets, and they would sing or not sing depending on the humidity that day or the brightness of the lights in a particular scene. But even though we left it basically to them, there would still be some days when I had to say, “This is just too much singing!” [laughs] On a day like that I would ask the crew during the performance to please take a few out of the cage.

- I was sure that the cricket sound was something the sound technician ZAK had pre-recorded and mixed into the soundtrack. Since the audience and stage where reversed for that show, the sound room had been moved out into the audience area. Was all that planning done by ZAK?

- Yes. That was a rather important part of this production. An underwater speaker was placed in the pool of blood so that voices could be played from there and that made it possible to project the sound of Yamakawa saying his lines on several levels, and ZAK himself also created a number of sounds that way. In the cases of ZAK and the lighting designer Masayoshi Takada, I left most of the decisions up to them. If Takada came to me and said, “I’ve thought of a new plan today,” I’d say “OK, I’ll see it in the performance.”

- So, it is basically a work-in-progress.

- Is that what you call it? We had a mix of Yamakawa’s voice and strange instrumental sounds playing from the underwater speakers, but the choice of sounds was left up to ZAK, so I don’t even know what they are.

- As I watched Psychosis I got the feeling that there was really no need to follow the text of the play. I had the impression that the opening scene was enough in itself, and there were also other scenes in the play that seemed to be complete in themselves.

- In a contemporary play in translation like Psychosis we are working under the restriction that we can’t change the script at will, and there is a basic rule that we can’t cut out parts or change the order of the scenes. Honestly, when I heard that I thought it would be very difficult for me to mount this play. I was like, “Do we really have to include every single line? You must be joking.” It was a real trial for me, like some sort of ascetic training. But, because there are things that came out in me from that training and trials, I believe that was the value in having done that script in its entirety. It was the same when I directed Hirata’s Tenkosei (Transfer Student). There was something that came out naturally and spontaneously in the rehearsals as a result of having gone through the trials of the scene where the girl falls and the ending together with everyone. Conversely, I believe you can say that beginning from a state where you don’t know what the script is really about and working through the trials of bringing it to the stage can lead you to a discovery of what was really intended between the lines of the script.

- For the recipients [the audience] of those sensitivities you bring to the stage it can feel less like watching theater and more like you are listening to cool music or watching a live concert.

- Good music is something that you can often sense from the sound of the very first notes. I don’t usually listen to entire pieces of music, but also I feel that I can get the sound of the music without listening to the whole thing. Long ago, when I was doing the music for the Jokyo Gekijo theater company, I worked sometimes at the record room of the national broadcasting company, NHK, where I was told that I had free access to listen to tens of thousands of records and sound sources. I ended up listening to almost all of them. Of course it would have been impossible if I had been listening to the entire records, so I would put the needle down on the start of an LP and listen to the opening bars of the music. I did that with almost all of the records in that archive. And I found that you can often tell if the music truly has power almost instantaneously from the moment you put the needle down on the record. Of course, in a play it isn’t possible to give the audience just the first few lines like that; you have to carry it through all the way to the end, and that is what makes it so difficult.

However, I believe that it is good to present the entire package, including the parts that may seem like a waste of time. Maybe it is because I have long lived with animals but I seem to have a good capacity for tolerating that kind of time that otherwise seems meaningless. The daily walks I take with my 3-year-old daughter are long, about three to even five hours. During that time I have to constantly be in position in case something happens, so it can be exhausting when it lasts that long. But it is the same as in the rehearsal studio, where if you [as the director] are too removed it is dangerous, but if you are too close you can have too much of an influence, so I have to be constantly making decisions about how much distance I should maintain. As a result, I concentrate on that too much when I walk with my daughter and end up being exhausted at the end [laughs]. There are very few really interesting moments along the way, but I am still able to endure those hours quite well. - Hearing you talk about things like these walks with your daughter, It seems that while you are using your own body like a sensor to sense out many different things, and you are also interacting with the people around you in the realm of your artistic expression, including your daughter and your audience, and using them as satellite sensors to augment your own.

- I don’t know whether that is true or not, but speaking in terms of sensitivities, I really have almost no sense of my own “self.” When I am in the rehearsal studio working on a piece, I am always thinking only about the other people there. And, although I may not be having such great thoughts, I am always thinking about the others there. Well, you could say that I like people, and it is not only people, but really everything that I like. So I am always thinking about other people and I realize that there is really nothing that I myself want to do. However, as a director I am given the right of decision-making, and although I often feel presumptuous having to exercise that right, I use it in ways like saying, “I think it looks great when so-and-so is sitting here instead.” In that way I spend all my time focusing on so-and-so with absolutely no consciousness of my “self.” And, in that sense it is not stressful, because I am not trying to do something myself. My only intention is to try my best to think about that person in that time and place.

- I hear that you always bring your daughter to the studio.

- Lately, it is interesting to see how she learns parts of the lines from the plays. The lines she learns are probably the ones that have impressed her most, but the first one she learned was “Drowning in the sea of logic!” When she suddenly shouted out that line I said to myself, “Is that it? Why that? [laughs] She must have some kind of barometer inside her that gives it meaning. And just last night she recited again, “Do you think that it is possible for a person to be born into the wrong body? A long silence.” [laughs]

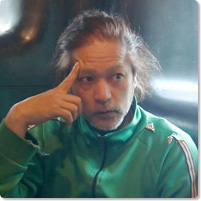

Norimizu Ameya

Norimizu Ameya, an artist who directs stages

with a strong degree of reality

Norimizu Ameya

Born in 1961. Norimizu Ameya joined one of the major troupes of the Underground Theatre Movement in Japan, Juro Kara’s Jokyo Gekijo in 1978, where he was in charge of the sound. In 1984 he formed the “Tokyo Grand Guignol,” rendering him cult popularity. In 1987, he founded [M.M.M.], a company working intensively on the relationship between mechanical apparatus and the human body. With the “SKIN” series, they established a cyberpunk scenic expression. After 1990 he left the field of theatre and began to engage himself with visual arts – still proceeding to work on his major topic – the human body – taking up themes like blood transfusion, artificial fertilization, infectious diseases, selective breeding, chemical food, and sex discrimination, creating works as a member of the collaboration unit Technocrat. After participating in the Venice Biennale with “Public Semen” in 1995, he suspended his activities as a visual artist. The same year he opened a pet shop in Higashi-Nakano in Tokyo, breeding and selling various animals. In 1997 he published a book, “Do you know how to live with animals?” (the title was later changed to “Do you know how to live with rare animals?,” when it was printed in paperback), where he not only gives information on the distinctions of, and how to breed rare pets, but also reflects on the co-habitation of humans and animals, based on his own experiences. In 2005, he presented a performance in the exhibition “Vanishing Points,” which marked a restart of his activities in visual arts after a long break. This is a work in which he is locked up in a 1.8 meter large white box. With only a minimum of fresh air and a fluid diet he stayed inside the box for 24 days, where knocking on the walls was his sole communication with the outside world. The artist’s presence was the elementary component of the artwork. In 2007 he directed Oriza Hirata ’s Tenkosei (Transfer Student) within the framework of the Shizuoka Performing Arts Center’s (SPAC) “SPAC autumn season 2007,” casting real high school students. The work was also performed at the Festival/Tokyo 09 Spring.

Ameya participated in Festival/Tokyo for four consecutive years with works like 4.48 Psychosis , using foreigners who have emigrated to Japan, and in Romeo Castellucci’s omnibus outdoor theater work Jimen set on a dream island. In 2012, he presented a touring performance named Iriguchi-Dekuchi (text by Mariko Asabuki) based on fieldwork on the Kunisaki Peninsula of Oita Prefecture. In addition to his theater making activities, Ameya also engages in experimental works with contemporary visual artists and musicians. In 2013, he worked with students from the Fukushima Prefectural Iwaki Sogo High School that was struck by the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami to create the play Blue Sheet that won the 58th Kishida Drama Award.

(Interviewer: Art Kuramochi)

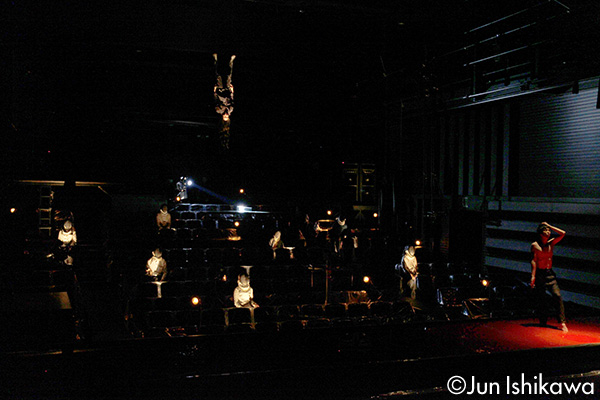

Festival/Tokyo 09 Spring Program

Transfer Student

(Mar. 26 – 29, 2009 at Tokyo Metropolitan Art Space-Medium Hall)

Produced by Shizuoka Performing Arts Center (SPAC)

Written by Oriza Hirata

Directed by Norimizu Ameya

https://festival-tokyo.jp/09sp/program/transfer/index.html

Photo: Jun Ishikawa

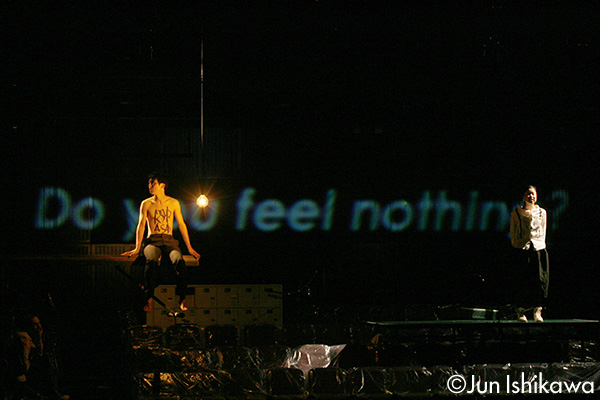

Festival/Tokyo 09 Autumn Program

4.48 Psychosis

(Nov. 16 – 23, 2009 at Owlspot Theater)

Written by Sarah Kane

Directed by Norimizu Ameya

Photo: Jun Ishikawa

Related Tags