- Could we begin by having you tell us about your upbringing?

- I was born in Osaka, but I grew up in Kitakyushu City from the age of three to age 18. My father was a company employee, and I have two older sisters.

- What kind of life did you have as a child? Did you take lessons in anything?

- I took classical ballet lessons from the age to three until I was twelve. I liked dancing, but I also knew I could never be a perfect ballerina. I was taller than the other girls and in the process of trying to stay in line with them my posture got steadily worse, and from the resulting complex my personality gradually grew introverted. When we were preparing for our ballet recitals, I didn’t have time to play with my school friends either, and I didn’t like that. So, I wanted to change my situation and decided to go out for the basketball team when I entered middle school. The kids on that team were an interesting bunch, and thanks to that, I became more extroverted again.

- Did you have any hobbies? Did you get into manga comics for young girls, etc.?

- I liked the Sailor Moon comics. I also collected dolls. Like the Jenny dolls and the Timotei (*1) dolls, and I really like the kid dolls. Everyone else naturally quit playing with dolls when they reached about the third grade of elementary school, but I remember that it being really hard for me to quit. Looking back, it may have been something of an awakening of sexual consciousness, because I liked taking off the dolls’ clothes.

- We are told that you began theater in high school, and could we ask you how that came about?

- In my third year of middle school everyone around me was busy preparing for the high school entrance exams, and the thought of that frightened me. It wasn’t that my school grades were that bad, but I just didn’t want to study just to take entrance exams, so I chose a high school with a ballet course that had an admissions system based on school grades, interview and recommendations, rather than an exam only. At the interview I said that I wanted to become a stage actor. At that school, we had regular required academic subject classes in the morning and in the afternoon, we had ballet, traditional Japanese dance and theater classes. The teachers of the theater course were former theater-makers like Shotaro Arikado of the TOBU-GEKIJOU (Flying Theater) company. That got me interested in the Kitakyushu Performing Arts Center, and I began going to workshops and the like organized by Center’s theater.

- The Kitakyushu Performing Arts Center that opened in 2003 is a theater base for the Kyushu area. Theater works invited from Tokyo and the like are also staged there I believe. Did you go to such performances there?

- Yes, I did. Sometimes I would also take a plane to Tokyo by myself to see performances. I would search for things I wanted to see on the internet and then go to see productions of works by people like Keralino Sandrovich, Keishi Nagatsuka and Yukiko Motoya. I also took the Shinkansen bullet train t Hiroshima to go see productions. Looking back, I guess I was very ambitious about seeing theater. That may have been the time when I loved theater most. (Laughs)

- So, what you were seeing was not commercial theater but alternative theater by the distinctive playwrights and directors of the small theater movement, weren’t you?

- I guess I had a sense that the alternative sub-culture type stages were cooler than the mainstream commercial theater fare. I think I was trying to look, and act cool myself. I also read a lot of plays. I was looking for plays that we could do, and I found and read plays like Oriza Hirata’s Tenkousei (Transfer Student).

- How about encounters with novels or manga works?

- I my first year of high school, I had a friend who got kicked out of school for using a dating website to find men to sell her socks to, and after that a bunch of other classmates were soon gone too. It was then that I found out that the man who bought her socks didn’t get punished at all, and with that I came to hate the school and society, and men in general. I thought, why was it only my friend who was punished? She just wanted money and she sold something that could get her money, so why does she get kicked out of school for that? Isn’t the man who bought it just as bad? I had nothing to do during breaks anymore, so I started reading Haruki Murakami’s books. As for manga books, I liked Kyoko Okazaki’s (*2) . I liked reading things that were popular among the young people of the next older generation than me.

- What was it Kyoko Okazaki’s works did you identify with or respond to?

- I wonder what it was. In high school, I think I was trying to act more mature than I really was. I think I wanted to say that I “understood” Kyoko Okazaki. I don’t think I had any special emotional problems or such, but there were quite a few times when I stayed out away from home, I was really living a wild, carefree life. It was not a very serious student body, and mostly girls, most of whom were dating boys from other schools. We talked about all kinds of things frankly and without reservation. It was not a very intelligent school. I think there were a lot of things that I was anxious to know about. But after my friend got kicked out of school things settled down to a rather normal high school life for me.

- Do you think that the private life you led in high school has influenced what you are writing today

-

Well, I think there was probably a degree of influence on the early things I wrote. But I don’t think that influence is there anymore. When I think about it, it was a rather dangerous time in my life. I felt an awareness myself of the kind of excesses that are common to puberty, and I also had an awareness that the people around me were looking at me that way. There were times when I felt that just one step in the wrong direction could have got me caught, and I also might have quit school. And I think that in my early writing there was a presence of those dangers that adolescent girls are susceptible to. I had the feeling like, no matter how much I was out running around having fun the day before, it was OK as long as I went to school the next day, so it was alright to pretend to be a serious student, because there is more than one world. I think the feeling that there are a lot of things out there to pick and choose from is one that I still have now. For example, I might watch someone and feel, “That person is deliberately acting like that way,” and I felt that there were times when I had to go out in front of some people acting as a person that I really wasn’t. That’s why, when I started writing plays, there were times when I felt that I wanted to write about the things that people usually had to keep closed up within themselves.

- Was there any particular thing that made you decide to do theater seriously at university?

- Certainly, the role of the Kitakyushu Performing Arts Center and my encounters there was a big impetus. I got a big confidence boost when I was chosen for a role like assistant to the director’s assistant in a drama reading produced by Masao Nouso and directed by Tatsuo Kaneshita, and it made me realize that I had been chosen by a professional director even though it was not as an actor. After that, I was given the role of Campanella in a production of Concept draft: Night on the Galactic Railroad (Written by: So Kitamura) directed by Atsushi Tomari, and from that I got the vague idea that this might be my future. So I enrolled in J. F. Oberlin University where Nouso-san and Kaneshita-san were teaching.

- Who were your instructors at university?

- For dance it was Kuniko Kisanuki, and I worked quite seriously in that course. For drama it was Yoshisada Sakaguchi and Hisao Takase (who were actor and director at Bungakuza. Unfortunately, both of them passed away. For me, I would have to say that Kaneshita-san was the biggest influence, and I auditioned for and got numerous roles in the student productions that he directed. At that time, I thought that highly stimulating direction and intense instruction was cool. I was able to play roles that I had never experienced before, like acting the part of someone going mad or thrashing around screaming or swinging a knife. I really loved it.

- For your graduation work in your senior year at university, you wrote a play script for the first time. We hear that you wrote it because you lacked the credits to graduate otherwise, and that work was titled Mushi Mushi Q (2010). That Q remains the name of your company today. May we ask what that Q means? Is it the Q of LGBTQ?

- No, it doesn’t really have any meaning. Writing for the first time, I wanted to write something that had insects ( mushi in Japanese) appearing in it from the beginning, so I planned to use the Chinese character for mushi . The letter Q looks like a ramen bowl with a little swirl design sticking out, and I thought it would be nice if it was seen more as a shape or symbol than a letter. Also, you can say that the letter Q looks a bit like the character mushi , and that is why I chose the title Mushi Mushi Q . I find the shape of Q appealing. When I was looking for a name for my company, I didn’t know how to decide on a name, so I thought that just Q wouldn’t be bad.

- When you were writing your first play script, was there anything that you took as an example? I can’t help wondering how you wrote a play for the first time.

- At first, I was thinking of writing a script for a performance piece rather than a play, so I got together a group of people to perform with me. They included Kyoko Takenaka, who is now active in Paris, Satoko Yoshida who has often performed in MUM & GYPSY productions, Misato Omori, who is now active in London and another woman who is now raising a child, and with me that made five. When I told them to just start dancing, what I saw at first, of course, wasn’t going well. So I knew I needed something for them to start from, and I decided to start writing the text on a garakei (*3) cellphone.

First, I wrote a very long monologue, and told everyone that this was how it would begin. From there, I decided that we would talk together about how it should develop from there, and I had them do improvisations and we took the good parts that came out of that. That was the process.- Why did you want to write a work in which there would be insects appearing?

- I have no idea. I guess the idea just came to me out of the blue that it would be interesting to have an insect like a mosquito come flying in and then stick someone with its stinger and then fly off. To suddenly have something unknown injected into your body and then have the injector suddenly fly off and disappear. With it would come the question of what it would feel like to have your blood enter a different living creature.

- The motif of exchanges and tradeoffs with different species of insects seems to be a consistent starting point for your work from the beginning until today.

- I feel that there has indeed been a consistent vein of that motif. I have consistently written about urine and feces coming out and about sweating. The feeling of fluids coming out of the body, thinking about where the fluids come from and the feeling of life force connected with them, those are all things I like.

- Excretion and sweating, they are all physiological phenomena. And things like the itchy feeling after an insect sucks your blood.

- I’m not the kind of person who has a wide range of interests or lots of knowledge. I still don’t have a lot of confidence in that area. If there are things that I can write about, I guess it is things that I feel confident about, like the physiological perceptions I have of things like the excretion of bodily fluids.

- There are descriptions that you write about clothing and things that are worn, such as whether the materials of panties are cotton or silk or wool, about how strong rubber is, and the writing style connects to physiological perceptions. Rather than objective descriptions of things you see, there seems to be more descriptions about physiological sensations like the feel of being licked on the rear by a dog.

- You could say that they are things that I have direct experience of, because those are the things I can trust. My desire to connect my works to direct experiences has led me to a preoccupation with writing about physical perceptions of the things around me. However, for example, if I write about human beings having sex with dogs it is not out of a desire to actually show people the act itself. What is important to me is what the audience experiences when an actor delivers those words as spoken lines on stage. If the lines induce a physiological feeling or response in the audience, I think that indeed is an essentially theatrical experience. But that alone will often lead to a dead end eventually, so I have also sought to grasp something larger, and that is what led me to try drawing on a motif from ancient Greek tragedy with my work The Bacchae #8211; Holstein Milk Cows.

- From your first works and on to today, you have tended to take up subjects that are normally taboo, like sexual desire and abnormal relationships with animals, the things people usually want to hide.

- I don’t have much interest in depicting the faces that I myself or others usually put on for the outside world. Whether it is with family or in love, people are usually acting roles to a large degree, and there is something false about that, I feel. I do that myself in daily life, so I don’t see any reason to do that in theater.

- Do you want to free the physiological sensibilities that are hidden within yourself?

- I inject something into myself and it changes form inside me and then is excreted out again. You could call it metabolism, I think. The body goes to work on it by itself without any deliberate intentions of my own. Even if there was something so painful mentally that you want to die, if the body’s metabolism is still at work, you can still feel the life force in you and feel proud of yourself for not giving up on life. I write because I want to express something convincingly.

- Said from another perspective, I feel that you are writing about people from a distance as if to say that even people who write about the truth also have there own lighter or less serious side. I think that lighter side you point to is interesting too.

- Those contradictory aspects are what make us human I think. With that premise, I think that writing boldly about those lighter sides can make things more interesting. In some sense, when I write about the less serious side of a character, you could say that I exaggerate boldly with a sense of outright prejudice against the character. And I think that deliberately exaggerating in that way can even made the role more convincing.

- How does your writing proceed? Do you write after deciding on a plot?

- At first, I write quickly, all at once by feeling, like an improvisational dance or music performance. If such-and-such a thing happens, it will be followed by such-and-such a response, like a process of intuitively associations. Rather than a process where you are writing descriptively based on an overall vision of a plot, the feeling is more like a quick succession based on reflexive reactions, “if this happens, it must be followed by that response.” When things are going well, I get a feeling like I am in a grove as I type. That is why I feel it is like improvisational dance or music performance. It is after that that I begin to put it all together and refine it. And I am thinking about the types of characters that will be necessary as create the plot.

- Are there any works that you particularly like personally?

- With The Question of Faeries (2017), there was a feeling of groove that I liked. It is basically a one-woman play consisting of three parts, a rakugo [comic] storytelling piece, a musical-style song and a seminar. That time I wanted to write about eugenic thought, and as an example of an expression used for a repressed minority, I chose to use the word busu (the Japanese word used for ugly women). In the world of this work, the women with average looks are called bijin (the Japanese word for a beautiful woman). Those who do not meet the standard of bijin are called busu . The reason that the vast majority of people are attracted to beauties is that the face has become the sign of the ability to birth healthy descendants in the course of evolution. It is believed that a woman with an average “ bijin ” face will not be lacking in intelligence or health. In the play, politicians claim that all busu should die. However, there is also the possibility that people with a face significantly different from the bijin norm can also be geniuses with a brain that is significantly more developed than the average person. So, in the story told in the first act of this play, which is told in the Japanese rakugo [comedy] storytelling style, a superior race is created by using plastic surgery to change such geniuses with busu faces into bijin , while keeping their genius intact.

The second act of the play takes the form of a musical-style song titled “Cockroach” ( gokiburi in Japanese). There is a poor couple who live in a house overrun with cockroaches. One day the husband tries to exterminate the cockroaches using a smoke-type insecticide. The song goes on to tell that, as a result, only the cockroaches that have a deficiency that makes them immune to the insecticide—in other words cockroaches with disabilities—survive.The third act takes the form of and a health seminar about “vaghurt,” a type of yoghurt made with a normal bacterial flora from the vagina of women. It is an attempt to affirm the value of human life by accepting the bacteria.- Is this a reflection of your worldview that with the weak and the strong, with the ugly and the beautiful there is basically no superiority or inferiority and no winners or losers?

- It is not that this is my personal worldview but a result of my feeling that the contemporary world is headed toward a dangerous state, and by writing about those dangers with no reserve I wanted to create a work that there are opposite, alternative ways that we can look at things. The truth is that this work was inspired by 2016 case of multiple killings of patients at a facility for the disabled in Sagamihara. (*4) It was a painfully shocking incident that is hard to speak of, but it made me realize that there was something of the misguided eugenic thought of the perpetrator in myself as well. Starting from that realization, I thought that I had to find another perspective. So I created this work as an attempt to find a new affirmation of all human life though a method that was free of any kind of hypocritical values and through a means that I believed in.

- With your play Favonia’s Fruitless Fable that you presented the year before that, you were shortlisted as a finalist for the Kunio Kishida Drama Award for the first time.

- It is a story about a female office worker who wanders around back streets in search of genuine leather shoes instead of fake leather ones, but looking back now, I think I only had a vague idea of what I wanted to write at that time. Although it was vague in conception I think it shared something in common with the #KuToo Movement (*5) that occurred after that.

- When you first started writing, it was your own physiological phenomena that were your motivation, but recently have your interests expanded to include things like discrimination and other social issues and ethical questions?

- It started at a time when I began thinking about how I could increase the influence that my works had on people and society. When I wrote strictly about physiological phenomena, I would only get vague comments from the audience like, “It was quite powerful somehow,” or, “I identified with some parts of it.” Some people said they like that type of work, but I thought it wouldn’t be good for me to be satisfied with that level of work.

- In 2017, you began to have opportunities to perform abroad and have exchanges with foreign artists, like when you performed Favonia’s Fruitless Fable in Seoul. Did these new experience have an influence on your subsequent works?

- I believe it did influence my works. We presented Favonia’s Fruitless Fable at the Seoul Marginal Theatre Festival, but during the performance there was a technical failure and the subtitles stopped showing. We stopped the performance at that point and asked the audience if they wanted to see the rest of the performance even if it had no subtitles, and they said, “Yes, we want to see it.” After that, even though they did not know what the [Japanese] lines were saying, they were able to feel something from the action happening on stage and they responded to it by laughing and applauding for us. Although the subtitle trouble meant they didn’t get the meaning of the script, I felt redeemed by the warmth of the audience’s response. Before that, I was the kind of pessimistic person who absolutely wouldn’t believe in things like humanism, but it was then that I felt for the first time that I wanted to become a person who could do something for others. It was an experience that truly made me start to change. The festival director that time was the leader of Creative VaQi, Kyungsung Lee, and after that he invited me to participate in other programs as well.

- In December of 2018, you participated in a Korea-Hong Kong-Japan co-production of Me and Sailor Moon’s Subway Ride at the Namsan Arts Center in Seoul.

- While working on that production we did a lot of talking about our respective countries. They all had experience participating in social movements in their countries and were able to share their experiences and feelings about it, but I wasn’t able to contribute to those conversations because I had absolutely no experience working in social movements. For example, when they asked me about the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011 or the resulting nuclear power plant disaster, unlike them, I was unable to talk about anything I had done directly in response to those problems. The year 2011 was the year I graduated from J. F. Oberlin University and I was no longer a student just when the disaster struck and threw the country into a terrible state with everything messed up. I felt the change in society very strongly, and it hurt me to see it, but my reaction was to try my best to play it cool and say, “I’m not going to dwell on this all.”

At that time, a variety of people were voicing their opinions on the social networks and the media, but I couldn’t believe any of it. I felt that I was unable to know what the real truth was. And since I couldn’t find out the real truth about things, I felt I’d be a loser if I got involved. I believe I was protecting myself by taking that attitude. And I think the fact that I stuck to things that involved my own physiological perceptions in my works after that is the result of that mistrust and the way it made me seek things that I could believe in.As a result of that experience of not being able to talk well about Japanese society I started to look back and see the way I had lived until then. Then I was able to finally leave behind that negative attitude I hadn’t even realized I had been living with for so long and begin to think about why I had not been able to face social issues straight on.- In Korea they had the incident known as the Sinking of MV Sewol in which the former president Park Geun-hye had made a blacklist for getting rid of cultural figures who took a negative attitude toward him. And in Hong Kong there was the Umbrella Rebellion, and in each case there were activities who fought against those social ills. And if the equivalent social issues were related to the natural disaster and the nuclear energy issue, do you feel that you had failed to make any kind of commitment regarding them?

- Well, yes. They had been involved it their own countries’ movements so directly that I could almost ask if they were really that interested in those issues. They each had experiences of really “fighting” for those issues. One had lasting damage to an eye due to tear gas at demonstrations, and another voice that opinion that, “The government was just terrible.” And that made me realize how different I was from them.

- The work you did after that, The Bacchae – Holstein Milk Cows won the 64th Kishida Kunio Drama Award.

- It was actually before that when I decided to base a work on a classical Greek tragedy. I was given the opportunity to present a work as part of the Aichi Triennale and I felt that would be a big opportunity for me in terms of my career. I knew it would probably be performed before audiences several times larger than any I had performed for until then, so I was determined to do something special. The theme for that year’s Aichi Triennale was “Taming Y/Our Passion” and I was inspired by the essay that introduced the theme’s concept. The Chinese character Jou used in the Japanese version of the theme equating the English word Passion has several meanings. We as human beings can be misled by our “passion,” but it can also be a “passion” of a different type that becomes a human being’s salvation. So, we have to “tame” our passion.

- From among the Greek tragedies, what was the reason you chose The Bacchae ?

- More than anything else, the reason I chose The Bacchae is my attraction to the character Dionysus (Bacchus). From the moment I discovered the character Dionysus, knew I could use it as a motif for the things I have been developing in my works until then, my signature themes of copulation between different species or crossbreeding. The reason I chose to use the format of the classical Greek tragedy, is that I wanted to write a music theater work.

For Favonia’s Fruitless Fable and The Question of Faeries, I had worked in collaboration with Masashi Nukata (*6) , and partly from that experience, I wanted to do something that used music effectively.- Dionysus was born of the union of a god and a human, and in your play The Bacchae – Holstein Milk Cows you replace him with a half-human, half-beast (child of a human and a cow). You also used the motif of half-human, half-beast or Centaur in your early works.

- An encounter with the unknown should be a truly intense experience. I have the feeling that compared to the love between humans, giving expression to a crossbreeding between a human and another type of animal, for example, should offer the possibility of a deeper examination into human nature.

- When is a case of two human beings, there are any number of different factors that can come into play, but if you are just dealing with a male and a female, there is no need to consider those other aspects, In other words, it frees you from the confines of human-based humanism, doesn’t it? But, by the way, why did you choose a cow in this case?

- I had for some time been interested in the profession of an animal inseminator. And taking the fact that Dionysus was a hybrid of a god and a human, I got the idea of a story in which a livestock artificial inseminator creates a hybrid between a human and a cow.

One of the consistent themes running through my works is that are written with the premise that, “Isn’t it strange to have a human-centric world?” On stage there is a rule of “equality” in that all of the living things, including human beings are played by human beings. However, all of the conditions under which they exist are not equal. Having all of the living entities on the stage acted out by human beings serves to accentuate the fact that there is unfairness in the conditions under which they exist and the inherent strangeness of human beings.- The performers in your play The Bacchae – Holstein Milk Cows were an all-women cast. Also, much of the attention you receive is as a female writer. Do you feel that being called a female writer influences what you write?

- In classical Greek theater, all of the performers were male, but I reversed that picture by having an all-female cast. The idea came to me out of the blue, but in the end, the creative process went smoother than ever before. There is always some degree of tension that emerges between the two sexes. But this time the rehearsal studio was overflowing with the relaxed and free-flowing power enabled by the all-female cast.

In the male-centric Japanese society, it is natural that women can’t help but experience a sense of anger just from the fact that they are women. However, when I started making theater, there was no plan to write about women. And when I started writing about my physiological perceptions, the focus naturally became feminine, because I have a woman’s body. When I started to be called a “female writer” instead of just a writer, it made me more conscious of the female aspect. I also came to be invited to more female-themed festivals and projects.The social framework of Japan’s theater world is also a male-centric society. Although there are a growing number of female theater-makers recently, the majority are still male and it is the males who are mostly in the positions of authority. Since in the end I am writing works that focus on women, to some degree I am also seen as a writer who uses the theme of women that is “recognized” by the male-centric establishment. The act of being “recognized” is of itself a male-oriented process, and the society that recognizes me functions on a male-centric model. I do have a desire to be recognized, but at the same time I have the resentment that comes with being a woman. While there are no easy answers, focusing on women is something that I have been doing with awareness for a long time.- I would like to ask you about the last scene of the play. The housewife, who is the equivalent of Pentheus, fights with the half-beast(=Dionysus) and finally cuts out its sex organ.

- Yes, and then takes it home and eats it as Korean-style grilled meat. This is related in part to the festival’s Taming Y/Our Passion theme, and what I wanted to say was that although the world wants a clear black or white conclusion, it is not easy to divide things so clearly. So, it is a final scene that can be interpreted in various ways.

- As an ending it definitely had the feeling of being neither definite or indefinite, and a sense that there might still be yet another surprise reversal of fortunes. The way it refrained from giving us a definitive ending gave the feeling that there could be one reversal in the plot after another due to the extreme simplicity of the interrelationships between the characters.

- I didn’t want it to be received with the kind of value system that enables a clear division between winners and losers. It may seem at one level that the one that got eaten was the loser, but since the half-beast wanted all along to become one with its mother (the housewife), it can also be said that its dream finally came true. It also may be that having its genitalia removed freed it from the struggle for reproduction. On the other hand, being able to eat the meat can be seen as a victory for the human being, but nothing changes for the housewife and she must still go on and on leading the same life. From the standpoint of people who have no house and no money, that may look like happiness. However, in the context of the society’s fraternal family system and consumer lifestyle, it can also be seen as a curse to grow old and die that way that the housewife is unconsciously burdened with due to a lifestyle where she has always put herself first.

- Having heard this, I get the feeling that this play represents a culmination of all the thing you have experienced until now. Are there any things you can tell us about now that you think you would like to do in the future?

- It may sound a bit hypocritical, but I would like to be able to do for others now some of the kinds of things that I have been fortunate enough to have others do for me until now. I have already been asked to serve as a judge on the juries of contests for works of performances and I want to become someone who is able to make well-based judgments of talented artists in those opportunities. I also want to actively pursue creative work overseas. Last year, there were several occasions that gave me renewed consciousness of myself as an Asian. And although there were cases where I had misgivings, I hope that this realization will motivate me toward new creative activities. In addition to my experiences in Europe, there have been chances for me to participate in talk events and the like held in Southeast Asia in recent years and I have been able to meet people there involved in theater. I have been inspired by their efforts to create places and connections in the Asian region.

- Do you have any images in mind for your next works?

- Right now I am taking Madame Butterfly as a point of departure to think about Orientalism with regard to Japanese and Asian women and, conversely, Occidentalism as well. Madame Butterfly was written about 100 years ago as a melodrama full of preconceptions and prejudices, but I think that on a fundamental level, those preconceptions have not changed much in the meantime. It is a story that looks at the Japanese woman from the perspective of a Western man, but I want to reverse that and rewrite it as a story told about the Western man through the eyes of a Japanese woman.

- That means that you want to use the story of Madame Butterfly express the discomfort that Asian women feel, right?

- Once when I was drinking in the Roppongi district of Tokyo frequented by foreigners, I saw lots of girls with long black hair who obviously liked foreigners. In Asia there are lots of districts like Roppongi. These women that we can see as modern-day Madame Butterflies don’t look like they are really seeing the actual individual faces of these Caucasian males but just see them all as the “whites” that they indiscriminately long for. In other words the women and the men are seeing each other with discriminatory eyes. And by pursuing each other without denying their own discriminatory preconceptions, they are suffering and enjoying the mutual pursuit. This is perhaps something that can be said about all human relationships to some degree.

- When will we be able to see this newest work?

- We did a reading-performance of Madame Butterfly at Theater Commons ’20. https://theatercommons.tokyo/) I see this a work-in-progress that I want to continue working on. In 2021, I am going to be doing a collaborative project with a theater in Zurich and it is there that I want to present it as a new work.

*1 The Jenny doll series with changeable costumes was released by Takara Tomy (formerly Takara) in 1986 (as an older sister to the Licca-chan series for younger girls). The Timotei dolls were launched as a friend of Jenny’s with the characterization of a flight attendant with long blond hair.

*2 Kyoko Okazaki was born in 1963 and is a charismatic female manga artist. Her works captured the atmosphere of the era from the 1980s into the ’90s and reflected the discomfort in living in that era in earnest lines of conversation. Her works like Tokyo Girls Bravo,pink,The River’s Edge and Helter Skelter became bibles for young women seeking to break out of the constraints of society.

*3 Garakei An abbreviated form of “Galapagos keitai,” with keitai being the Japanese name used the old fold-out type cellphones before the evolution to today’s smartphones.

*4 The Multiple Stabbing Incident at a facility for the disabled in Sagamihara The case of multiple stabbings and murders of patients at the Tsukui-Yamayuri-en facility for the disabled in Sagamihara, Japan on July 26, 2016. A former male employee of the facility entered the facility undetected and, claiming that the disabled are better off dead, proceeded to stab to death 19 of the disabled patients and cause various degrees of injury to 26 other patients and staff members. The words and actions of the perpetrator claiming it was a crime of conscience shook the entire nation.

*5 #KuToo Movement

This was a movement protesting the fact that many Japanese workplaces required their female employees to wear high-heeled shoes or medium-heeled pump shoes. The #KuToo hashtag that spread with the movement was derived from the #MeToo movement’s and played on the two meanings of the Japanese words kutsu (shoes) and kutsuu (a pain).*6 Masashi Nukata Born 1992, Nukata is a composer and director. While a student at Tokyo University of the Arts, he formed an eight-member band named TOKYO SHIOKOUJI that specialized in breakbeat and minimal music. He also established the theater company Nuthmique in 2016 and won the Grand Prix of the 16th Aichi Arts Foundation Drama Award (AAF Drama Award) for the play The Town Thereafter. He has also composed many music pieces for the stage.

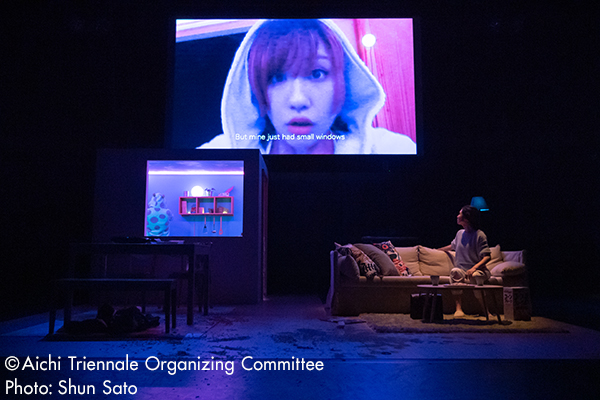

The Bacchae – Holstein Milk Cows

Despite the domination her husband subjects her to, the Woman in the lead role relinquishes herself to the security of life as a housewife. Before marriage she had worked as a domesticated animal inseminator and now she decides to buy some semen from a donor over the internet and half in fun she injects it into a cow. It results in the birth of a half-human, half cow Holstein beast with a large clitoris that can ejaculate semen and becomes its mother. She abandons the child beast when it is three years old and it is left to support itself as half-human, half cow selling her favors to perverted men.

(Aug 11-14, 2019 at Aichi Prefectural Art Theater-Mini theater)

©Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

Photo: Shun SatoRelated Tags

Satoko Ichihara

Satoko Ichihara’s Reality

Judged by a Unique Physiological Sensibility

Satoko Ichihara

Playwright, director and novelist, Ichihara was born in Osaka in 1988 and grew up in Fukuoka prefecture. She studied theater at J. F. Oberlin University. From 2011, she has led the theater unit “Q.” Ichihara is known for creating and directing dramas that deal with human actions and the discomfort of the physiological needs of the body with a distinctive use of language and physicality. In scripts that treat with frankness the subjects of sexuality or intercourse and interbreeding between different species or races from a female point of view, the audience can be showered with words that are physically stimulating and the actors on stage may use devices like caricature or at times showing their own faults as they act out the script with full physical output and expression. Her plays to pose questions about the validity of the way subjects like sex and breeding have conventionally been defined from a male-centric or human-centric perspective but now becomes invalid, and she can also use radical means to question the ethical and moral perspective that have been defined for society’s majority.

Ichihara has been a Junior Fellow Artist of the Saison Foundation.

In 2011, Ichihara won the 11th AAF Drama Award for her play Mushi (Insects). In 2020, Ichihara’s play The Bacchae – Holstein Milk Cows won the 64th Kunio Kishida Drama Award.

In June of 2019 Ichihara’s short story collection Mamito no Tenshi was published by Hayakawa Publishing Corporation.

Interviewer: Masashi Nomura [Theater producer, dramaturg]