YumeiOtotoi (restage)

(Sep. 8–12, 2017 at ST Spot)

Approaching a new type of theater that reciprocates with reality

Ryo Ikeda of the digital-native generation

Photo: Atsuharu Ino

Ikeda is a playwright, director, actor, and visual artist born in 1992. He earned his master’s degree from the Graduate School of Fine Arts, Department of Sculpture, at Tokyo University of the Arts. In 2015, he became a founding member of the creator’s collective yumei. Always passionate about creation, Ikeda’s practice spans writing, directing, acting, sculpture, model-building, stage prop design, and video production. In addition to writing and directing for yumei, he has written for Tensai TV kun (NHK Educational TV) and served as scriptwriter and story planner for the anime Umamusume: Pretty Derby. He also manages the handmade goods shop TOY FUKURO, and is an active capsule toy designer, producing items such as the “Kurisutaru Handoru Suisen Ringu (crystal handle faucet ring)”. His representative works include Ototoi (brothers), Aka (Red), Sugata (Shape), and Heartland, which he wrote and directed (68th Kishida Kunio Drama Award), Yojo (Curing) (32nd Yomiuri Theater Awards Excellent Director Award), for which he served as writer, director, and scenographer, Terayama Cabaret, directed by David Leveaux, starring Shingo Katori, and for which Ikeda wrote the script, as well as Sphere of Sphere, for which he also served as writer, director, and scenographer. (Updated in October 2025)

YumeiOtotoi (restage)

(Sep. 8–12, 2017 at ST Spot)

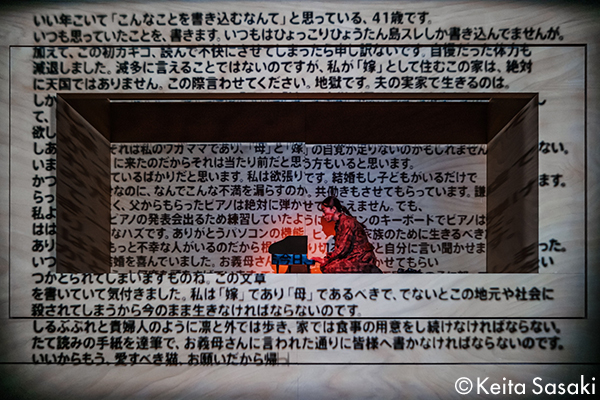

Yumei aka aka

(May. 28–Jun. 5, 2022 at Kawasaki Art Center-Alterio Small Theater)

Photo: Keita Sasaki

Yumei Sugata (reestage)

(May, 18–30, 2021 at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre- Theatre East)

Photo: Keita Sasaki

Yumei Musume

(Dec. 22–29, 2021at The Suzunari

Photo: Keita Sasaki

(→“Play of the Month” Musume)

*1 Nekama

This is a slang term that means that a man behaves like a woman on a Net where their authenticity cannot be confirmed.

*2 Uma Musume

This is a smartphone game app and PC game by Cygames that personifies racehorses as young women. In a training simulation game, you develop your character and aim to win the races. The anime work based on the game was also a big hit.

Related Tags