- To date, you have been active spreading Nihon Buyo (Japanese traditional dance) to more than 20 countries overseas. In 2016, you visited the ten countries of the Czech Republic, France, German, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Russia, Slovakia the Ukraine and the United States as a Cultural Ambassador of the Bureau of Cultural Affairs. When was it that you began activities overseas?

- My grandmother began looking overseas from quite some time ago. She had students in Honolulu, Los Angeles, Seattle, Vancouver and Brazil. After World War II when Japanese began to move overseas, Nihon Buyo began to spread with them to various countries, and it wasn’t just my grandmother but the master dance instructors from the various schools of Nihon Buyo were also teaching overseas it seems. My mother gave her first recital in New York in 1967, and you could say that my first overseas activities were when I went along with my father and younger brother to assist her.

- What kind of lectures do you give on Nihon Buyo when you go overseas?

- First of all I begin by explaining the name Nihon Buyo. If you say Nihon Buyo with the literal meaning of “Japanese dance” it includes all kinds of dance. So, I first explain that Nihon Buyo is a form of performance art that is primarily for the purpose of performing on stage in front of an audience.

Then I talk about the history of Kabuki and how it is the direct roots of Nihon Buyo. The origin of Kabuki is said to be the “kabuki odori” (kabuki dance) of a woman named Izumo no Okuni (1572 – ?). Since this was a sort of review dance where many dancers danced at once to a new kind of music played on the shamisen, with at the time was the latest instrument to be imported into Japan, it means that from its birth, Kabuki and dance were inseparably linked.

After that, the “Okuni no Kabuki” performed only by women and the eventual birth of “Wakashu Kabuki” performed by young boys as its successor were both banned by the Edo government as performance arts that corrupted the public morals, then only mature males were allowed to perform Kabuki and its stories were limited to old tales of warrior heroes or melodramatic stories of the lives of the common people. But these government restriction would lead to the establishment of the art of males performing female roles that is unique in the world and a type of dance that included elements close to pantomime. It was as a part of this performance art history that Nihon Buyo developed, and performers who became skilled at this dance came to perform various roles using fast costume-change techniques, which gave birth to “Hengemono” (role-change dances) styles like “Shichihenge” (literally “seven changes”) and “Junihenge” (literally “twelve changes”). Many of the dances that we learn today as Nihon Buyo are in fact select portions of the traditional Hengemono.

By the early 1800s, dance played an increasingly important role in Kabuki, leading to the birth of dedicated choreographers. At first, the Kabuki actors themselves though up appropriate dance movements, but the need to communicate the moves to other actors probably led to the forming of the dedicated choreographer as a profession. That, in turn, encouraged more people to want to learn to dance and the job of the professional dance instruction by master dance teachers was born. We are the direct descendants of these masters. - As a form of dance that grew out of Kabuki, the dramatic narrative aspect of Nihon Buyo is very strong, with the dance wearing a costume and acting out a specific role with dance. In addition to this type of dance, however, there is also a type called Suodori in which a single dancer wearing no costume or wig acts out multiple roles solely through dance. How do you explain Suodori to people?

- In ballet for instance, there may be rare cases where the white swan changes into the black swan, but there will never be a case where it will change roles and become a prince. In Nihon Buyo, however, the same dancer can perform the role of a princess and a prince. What’s more that same dancer may also express the blooming of flowers and the blowing of the wind in the same dance. I explain to people that Suodori is the form of dance performance that exploits this potential to the fullest. For me, it is only natural that people overseas are surprised to learn of the existence of such a dance form. Seen in other way, however, if I don’t explain this unique aspect of Nihon Buyo, it might be misunderstood as a dance by a person with multiple-personality syndrome. So, when I am explaining about Suodori, before I actually begin the dance I will demonstrate, I explain the key points, such as the fact that at a certain point I will be dancing the role of a woman and then the role will change to another role.

Suodori is a form of dance that became established in Japan’s Meiji Period (1868-1912). As a translation of the word “dance” that entered Japan from abroad at this time, Tsubouchi Shoyo (1859 – 1935) took the Japanese character mai and the character for odori (both meaning types of dance) and brought them together to create the compound word buyo. This started a new dance movement to create a uniquely Japanese form of dance (buyo). With this, buyo became independent from Kabuki and the Buyo artists began to search for new forms of expression in dance.Suodori actually began as recitals for the dance students to show the progress they had made through their daily lessons, and at the end the teacher would come out on stage without any specific costume (in other words in the su (unadorned, un-costumed) state and dance a number of roles depicting various scenes and finally leave the stage having returned to the su state. In this way, the teacher’s final Suodori performance became increasingly a show of the teacher’s individual skills as a dancer. And thus, this Suodori came to be a pure show of the physical movement various dance roles without any specific stage art, costume or makeup. The men dance the Suodori in their normal hairstyle with no wig and wearing a formal kimono with family crest (montsuki) and a separate male skirt (hakama), and the women wear a black kimono with decoration only at the hem (tomesode) with white face makeup and a “maeware” style wig. By the way, the maeware (parted in the middle) wig is designed to represent the hairstyle of [male] Kabuki female-role (onnagata) actors who wore a wig over their own hair parted in the middle. The total effect is to represent a Kabuki onnagata actor’s appearance in black under kimono before putting on the Kabuki costume. - Are there any other things that you explain in your introductory lectures on Suodori?

- I explain about Mitate. In the year 2000, I went with my mother to perform in Ireland at the request of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and after that we spend about one month touring Turkey, Syria and Lebanon. That trip made an especially strong impression on me in terms of what I experienced about the uniqueness of the Japanese traditional dance that we call Nihon Buyo. One unique aspect is of course the fact that a single dancer is dancing a number of roles and scenery, and the other thing I became strongly aware of is the uniqueness of what we call Mitate.

There are several forms of dance from various parts of the world that use fans, like Flamenco for instance, but in them, the fan is used only in fanning motions. In Nihon Buyo, however, it is different. If we close the fan and bring it to the mouth, it represents a Japanese kiseru tobacco pipe, and if we stand the closed fan on end, it represents a bottle of sake rice wine. And when open it can also be used to represent a mountain and the wind, and it can also be used to represent flowers blooming. That is what we call mitate. It is very hard to talk about mitate in a foreign language. As a result, I explain mitate as using X to represent Y. In this explanation, I say that the X is the fan and the Y can be mountains or wind, or water. This is a form of expression unique to Japanese culture, not only in dance, but also in Waka poetry and literature and in the tea ceremony and flower arrangement, as well as in the worlds of painting and Japanese cuisine. I explain in advance that they all use mitate before I give my demonstrations of it.

One easy to understand example of mitate is closing the fan and holding it vertically, then tilting it as if pouring into a cup, and when you make the action of drinking it and then moving as if you are drunk, it is easy to get the picture of a person drinking alcohol. The audience gets that picture because they realize the standing fan can represent a bottle of sake rice wine. If I explain that that is mitate, it is convincing to them. Then I perform a number of other examples. I open the fan and turn it upside-down to form an inverted V to represent a mountain, etc. For Japanese, the representative mountain is Mt. Fuji, which stands alone as a near-perfect inverted V, so we see it as a mountain. But in Russia, for example, mountains are seen as mountain ridges, so it is difficult for them to see the inverted V of the fan as a mountain. - In other words, mitate depends a lot of the cultural background, doesn’t it?

- Yes. Every year I have the opportunity to lecture to foreign students on Nihon Buyo, and when I do, I hand out fans to them and explain about mitate. Then I have them use the fan to represent something of their own. When they do, an American may open it and lay it flat to represent a pizza, or a German student may stand it up closed to represent a beer. It is fun to see how the different cultural backgrounds show them selves.

- Besides working for the spread of classical Nihon Buyo, you have been actively choreographing new Nihon Buyo pieces inspired by Western subjects. The work Magakami you created and presented in 2009 made Nihon Buyo work based on Goethe’s tragic play Faust.

- When I first began doing original new Nihon Buto pieces, I had decided that when doing my own works I would always use traditional Japanese music (hogaku) and the costume would be Japanese kimono. In the case of Magakami, I did it in the Suodori style with myself dancing all the role, including Faust, Mephisto (Mephistopheles), Margarete, the witches and other people, by myself. I did the choreography, the directing and wrote the words (Nagauta lyrics), and for the music I asked Kineya Katsushiro (a Nagauta shamisen player and singer) to compose it. What made me decide to do it was being asked by the Kabuki actor Nakamura Baigyoku to choreograph a Nihon Buyo dance for him to dance to a piano performance of a Mephisto Waltz. As I read Faust in preparation for that, I thought that it was a play that could be danced. When I wrote the words for it and showed it to Katsushiro-san, he replied that it would be very interesting to compose for, and he did.

- For your new original works you often collaborate with Kineya Katsushiro for the music, Renta Kochi for the stage art and Hisashi Adachi for the lighting.

- I have worked with this group of stage collaborators since our 2007 production of Oki-no-Tayu. Oki-no-tayu is the old name for the short-tailed albatross. When I happened to see a documentary on the short-tailed albatross on television I suddenly got the idea for a story about an albatross that falls in love with a beautiful decoy intended to attract the birds. When I wrote the lyrics to this story as my first solo work of Suodori, I asked Kineya-san to write the music for it. When I was thinking that I wanted to have especially effective lighting, I happened to be performing in a Nihon Buyo Association stage production of a new original piece that had such wonderful lighting effects, I asked the lighting planner, Hisashi Adachi to do the lighting for my work as well. Then Adachi-san introduced me to Kochi-san, who devised the albatross decoy with a wooden frame that kimono was draped over and a mechanism that made it crumble down at the critical moment in the play.

- What are the kinds of things that make you want to create a new original dance work?

- In my case, my desire to create a new work doesn’t come from ideas about what kind of dance I want to do or what kind of role I want to act out. Rather, I am inspired to create a new work by a story that I am attracted to and the feeling that it would be fascinating to try to turn it into a dance work. So, I really enjoy writing the lyrics that will be danced to, but when I start to set the choreography to it, I come up against the daunting questions of what the writer of the original story was thinking of and, “How can I ever turn this into dance!” It is then that I find myself getting mad at myself every time for taking on such a task (laughs).

- Isn’t it rare to have a choreographer who also writes their own stage scripts and lyrics?

- I wonder if it is. My scripts have stage direction about settings and they have lyrics, and with the stage directions there are narrations that give descriptions of the situations and emotions involved, and as for conversation between characters, I put those in the form of lyrics to be sung [as recitation].

- Are the lyrics you create written in the traditional Uta (poetic lyric, poetry) style?

- While writing and rewriting several times, I get it into something close to the usual five-seven-five syllable-per-phrase form of traditional Japanese Waka or haiku poetry, thus putting the words into a regular rhythm. However, if it is all that way, it becomes rather flat, so I deliberately include extra syllables (ji amari) at places. In Oki-no-Tayu, almost all of the lyrics were written in contemporary Japanese, which drew mixed responses, positive and negative. It was criticized quite a bit by people who are used to listening to traditional Japanese Hogaku music. I thought it would be meaningless if people couldn’t understand the lyrics [if written in old Japanese], but it made me think that it might have been better to write it in Japanese that fits well into the Hogaku music. With Magakami, some of the Japanese translations of the play Faust that I read were done in older Japanese style from the Meiji and Taisho eras (late 19th, early 20th centuries), so if fit into the Hogaku music well.

- Since you also perform Nagauta singing/recitation and the Hayashi instrumental accompaniment, it seems that you would be able to compose the music as well. Why do you not do it?

- When the person who writes the lyrics also composes the music, there is a strong tendency to write lyrics that will fit well with the music one has in mind. But when you listen to the classics of Hogaku, you find that the breaks in the music are different from what would be the natural breaks in the lines of the lyrics, and though that may make the lyrics harder to understand, that difference is what makes it so interesting to listen to. So, I believe that having the writer and composer be different people is best.

- Kineya Katsushiro, who you use for composing the music for your original works, is a performer of Nagauta shamisen and song/recitation that dates back to the Edo Period. But he is also an innovative musician who started the shamisen funk band The Iemoto.

- It may be normal to ask shamisen performers to compose music in our profession, in my original works I want to stress the story, so I think about how to make more attention focus on the lyrics and I think about how to make the singing/recitation more interesting. That is why I asked Katsushiro, who is also a singer, to compose for me. He composes very interesting music, but since I am writing original works the musical image I want will often be different for each work, so there are times when I will make requests for him to revise the music he composes originally. I believe I can do that because of the important relationship of trust we have developed.

- In 2012, you wrote a Nihon Buyo version of the opera The Barber of Seville, changing the title to Adayojin (literally Mischievous Precautions), which was presented as the 18th Rankoh no Kai production. Was this another case where you were drawn to the fun and captivating nature of the story?

- Yes. I saw a video of a performance of the opera The Barber of Seville and I immediately thought it could be turned into an interesting dance work, so I set to work and wrote the lyrics for a stage production. Since I wanted to imitate the classical [Nagauta] style, I got a dictionary of old Japanese and made constant reference to it, as well as referring to a book of old classical songs. For the title, I devised a Japanese version of the opera’s secondary title, The Useless Precaution.

- In the original opera and stories you make dances from there are many characters, so for your Nihon Buyo works do you reduce the cast and rearrange the story lines?

- When I am working from an original story, I basically follow the original cast and storyline. With Magakami as well, I made Mephisto (Mephistopheles) the main character and included Faust and Margarete, three witches and other people in the cast and danced all their roles myself. In Adayojin as well, I intended at first to dance all the parts myself, as in Magakami. But that opera [The Barber of Seville] has many duets and trios and many people appear and act out roles on stage, part of the overall interest lies in that presence of many people. I realized that it would be impossible to convey that dancing lone, so I asked the members of our Goyokai group to join me in the cast.

This was partly because I felt that the different characters of the opera also fit the individual characters of the five members of our group perfectly. I played the role of Almaviva, and Hanayagi Motoi played the role of Figaro. In the adaptation, I set the story in Japan’s Edo Period, so I change the names of the characters. I changed Almaviva to Arima Rinnoshin, I changed Rosina (Rose) to O-Ume since the ume (plum tree/flowers is a member of the rose family in old Japanese. I had Hanayagi Juraku play the role of Rosina. Her adoptive parent [Bartolo] is played by Nishikawa Minosuke. Rosina’s music teacher Don Basilio is played by the Kamigatamai school’s master Yamamura Tomogoro, and I changed the name of the music teacher to Ban Dojuro. So it is completely a pun. - How is it that a master of Nihon Buyo enjoys humor so much (laughs)? What was it that got you into writing in the first place?

- Looking back, I think it was the script I wrote for the 30th Memorial Buyo-kai performance (1996) of the Joto Block of the Tokyo Branch of the Nihon Buyo Association that I belong to. There was to be a special appearance by the master teacher of the Kasuga school of Kouta (traditional Japanese ballad accompanied by shamisen), Kasuga Toyoeishiba, so a plan was devised to have a tour of the old and famous sites of the Joyo area appearing in Kouta classics. Taking this as an opportunity, I decided to write some humorous lyrics, changing the words of the classics, and I was given the opportunity to write the stage script. The scheme was to create a story in which the famous Edo Period painter and print artist Katsushika Hokusai goes on a tour of the old and famous Kouta sites of the Joyo district in search of the younger of twin brothers of the district that were famous for growing hakusai (Chinese cabbage), and the audience greatly appreciated the piece.

The people at the local Koto Ward office gave me support, saying that if such enjoyable things could be done with Nihon Buyo, they definitely wanted me to continue. As a result, we started and entertainment event at the Asakusa Public Hall from 2005 titled “Odori Live.” It consists of three performances, one of group dances by young Buyo artists, a classic piece and a dance theater piece using Kouta artists. Master Bando Katsutomo choreographed the dance theater pieces, while I did the stage script and the directing, and these events continued for about eight productions. The first one took the Nezumi Kozo story as its subject, the next year it was a Japan-set version of Pinocchio, then we did one on A Midsummer Night’s Dream and then Phantom of the Opera as well as parodies of Japanese Rakugo comedy and Kabuki skits.

Part of the reason these productions were possible was the character of the times, I believe, as well as the nature of the “Shitamachi” (downtown) locality. I ended up writing a lot of changed-lyric Kouta parodies in lieu of stage scripts, and I directed them, working with very skilled masters who added their own rich aspects to each work, so I learned a lot in the process. - Is the fact that you have been trained as the successor to your family’s school of Nihon Buyo influenced your additional activities as a lyric and stage scriptwriter?

- What I think has been fortunate for me is the fact that, as a college student I was, I was able to watch many plays by small-theater companies that were flourishing, one after another, at the time. I saw plays by the Daisan Butai company and Kazuyoshi Kushida and Hideko Yoshida’s On Theater Jiyu Gekijo. They were shockingly different and so interesting. But I also felt that if I left myself get absorbed in the small-theater world, I might not be able to continue doing Nihon Buyo. In my mid-20s, I was also going to orchestra concerts and to see ballet and opera productions, but I gave up doing that as well. I narrowed down my focus to watching only Kabuki and stage performances and Nihon Buyo.

- It is very interesting to hear that part of your background includes that encounter with the avant-garde art of small-theater plays when you were young. It seems to me that there is something in common between the way the small-theaters plays involved storylines that leap freely in the temporal and spatial settings and the way your Suodori works have you dancing multiple roles in a continuous piece.

- From the time that I was small, my grandmother and mother often told me about the importance of mastering the classics, and that there was no way you think of creating new works [of value] before mastering the classical repertoire. So, in my mid-20s I stopped seeing other type of performing arts until I was satisfied that I was competent in performing the classics of Nihon Buyo. I believe that it was a good choice I made.

In 1998, through the good graces of the wife of Nakamura Baigyoku, who herself had been a ballerina, I was able to choreograph for a joint production by Baigyoku and the Ballet Chambre Ouest company, and for that production, I didn’t watch ballet for reference but choreographed fully focused on Nihon Buyo. It wasn’t until after I married my wife (dance critic Takako Sakurai) eleven years ago that I started to watch Western dance/performing arts. And even if the subject or story I am working from is of Western origin, I choreography from my base in the Nihon Buyo classics. - In the play Nobunaga that you wrote, directed and choreographed, you had performing with you the world-famous ballet dancers Farukh Ruzimatov and Morihiro Iwata, so with ballet and Nihon Buyo you had representative dance forms of the East and West that are inherently different, but you didn’t choreograph in a way that amounted to a compromise on either form. And the fact that it came together as one comprehensive work seems close to a miracle.

- From the time of the rehearsals for the premiere in 2015, all three of us seemed have as our motto that the classics were of prime importance. Another motto we shared was that each of us should do what we were best at. So, it was something like a [positive] clash of the things that each of us had excelled in from the time we were young. That is the only way to work.

This approach of respecting the classics and giving each other the best we have is something I learned from the Nagauta story Shigure Saigyo. And, since it was going to be danced by the Kabuki actor Baigyoku, I choreographed it using solely techniques from classics. Even for scenes where ballet was being performed on the same stage at the same time, I had decided to use only the movements of Nihon Buyo in our dance parts. And when we took our parts to the ballet rehearsal studio to put the two together, we found they the two dance parts fit together perfectly. At that moment I felt a new type of realization.

Both Ruzimatov and Morihiro Iwata who collaborated with me on Nobunaga had an unwavering devotion to the classics that gives them an exceptional ability to bring depth to the role they are playing. They bring to the stage a very clear understanding of what they must do and the role they must play. And when you have that, everything is going to go well. - In 2009, you joined with four other Nihon Buyo masters of different schools to form the group Goyokai, and you continue to work actively together today.

- At the time, master Nishikawa Minosuke was saying the number of people doing Nihon Buyo dance and their audience were continuing to decrease, to the point where we were no longer in the eyes of the society. He had the strong sense of crisis, that I we didn’t work hard to correct this situation now our art will not be carried on to the next generation. As Nishikata Setsuko was preparing a book about the current state of the Nihon Buyo world, she interviewed me and Hanayagi Motoi-san, and she had the idea that it would be difficult for any one of us to make much difference, but what of the possibilities if a group was formed, and that led to the founding of Goyokai. With Minosuke as our leader, we formed a group of five with Motoi-san, Tomogoro-san Juraku-san and myself, and thanks to everyone’s good graces, the group has continued for 11 years now.

Our belief is simply that we have to do something for the future of Nihon Buyo. Our dance only has meaning if there are people, an audience to watch our performances. It isn’t an art for the sake of the performers, the important thing is that we give performances that please our audience. I believe it is not enough to just hold recitals for the students of Nihon Buyo and stages that please them. As professionals, we have to create works and performances that make the audience want to come back again to see us perform, otherwise we won’t grow our audience, and if the audience doesn’t grow there it will be a downward spiral in which there won’t be people who want to learn Nihon Buyo. - It seems that there are fewer people learning Nihon Buyo than in the past.

- Until the days when my mother was a child, Nihon Buyo was one of the five leading arts parents had their children learn. But today it isn’t even in the top ten. In dance there is ballet, hip hop, jazz dance flamenco, and besides that others things that fill out the most-learned subjects are gymnastics, English, swimming and piano. Nihon Buyo just isn’t among the things that parents want their children to learn. It’s no wonder, since most parents have never even seen it. So we have to get more people to see Nihon Buyo, not only in the parent generation but also among the grandparents, otherwise there is no way to expand the base of the art to build on.

- By the way, was there ever a group like yours in the past that drew from artists of different Nihon Buyo schools?

- Two generations before us there was a group named Gonin no Kai. It had five members in master Hanayagi Juraku, masters Fujima Tomoaki and Fujima Shusai of the Fujima school, master Saruwaka Kiyokata and master Yoshimura Yuki of the Kamigata school. They helped each other by creating bigger stage productions than a single master could do alone, and it was a very creative and studious group that created new works ambitiously. After that, the present master Senzo and master Juou and the late master Izumi Tokuemon formed the Sanjukai group. Since the three of them had been nurture under the eye of master Juraku from childhood, I believe they thought it would be an example for others if they formed a similar group of their own.

- After forming Goyokai, what kind of response did you get?

- We did performances of our first stage production at the Osaka Shochikuza Theatre and the Large Hall of the National Theatre of Japan in Tokyo. About two years later we began a program of studio-type performances called “Nihon Buyo e no Sasoi (Invitation to Nihon Buyo) – by Goyokai,” in which each of us members gave performances of parts of a dance piece and then gave an explanation of it. The aim was to help people feel more familiar with Nihon Buyo, and we held these events once a month on the 5th rotating the venue among the five of our own studios, and the admission was [just] 500 yen (at the start). Inviting our students would have been enough to fill the studios, but rather than doing that we decided to advertised the events to the general public on the Web. The first time, that brought an audience of 11, then 15 for the second event and in three or four months it was more than the facility audience limit of 60 people, so we had to initiate a waiting list system. After continuing that for about three years, we decided we have met our initial goals, so we have suspended the program.

- Besides those studio performances, what other activities have you engaged in?

- We only do our own group productions once every one or two years. But we have increasingly received invitations to perform at venues around the country as Goyokai. In March of 2019, we are performing in Okinawa. We are going to perform a new work based on the Okinawan hero Gosamaru at the Nakagusuku Castle ruins on Ishigaki Island, which is designated a World Heritage site. In front of the remains of the castle walls we will build a temporary stage to perform our dance on.

- You have also performed as Goyokai overseas, and recently you did a collaboration in India with local dancers and musicians.

- In 2016, through connections with the Japan Foundation and the Nihon Buyo Foundation, Goyokai was asked to do a collaboration in New Delhi with Indian musicians. For that project, we danced Sanbaso to a tabla accompaniment and Hagoromo to a sitar accompaniment. At the end we created about a five-minute long collaborative piece to perform with kathak dancers. That was especially well received, which led to a plan to a full-length work next time, and that resulted in the work Ramayana that we premiered in New Delhi in 2017. It had been half jokingly that we agreed that for an Indian story it should be Ramayana, but it turned out that that is actually what we finally decided to do (laughs).

So, they pointed to me and said, “OK, Rankoh, you write the script.” So when I got back to Japan, I got a book of Ramayana to read and I immediately began to wonder how I could make a script for such a huge story. But, since Nihon Buyo makes it possible for one dancer to dance multiple roles, I wrote it so I would dance the role of Rama and the others would dance three roles each. Since we would be dance in the usual montsuki kimono, we got the idea to wrap Indian fabrics around our kimono to give the audience a clearer idea of who was dancing what role. - Because it is one of the most well known Indian stories, you must have had some difficulties.

- We went to a seller of Indian fabrics and told them that we were going to be putting on a stage production of Ramayana and were there to but fabrics to symbolize the various characters in the story. So they came out with suggestions of proper choices for the different roles. We were told that the color that represents the monkey Hanuman in the play is orange, and when we asked for an orange fabric, there were comments like, “Perhaps it should be a darker orange.” Even one of the store’s customers joined in saying, “For Hanuman it’s got to be this fabric.” Since it is a story as well known in India as the Momotaro and Kintaro stories are in Japan, we were really nervous about how our rendition would be received. However, on the opening day, but when the lights went out at the end of the scene where Rama is exiled from the palace, we heard a big round of applause. So we thought, “Yes!” Then, at the end of the performance, the entire audience rose to give us a standing ovation.

- Did you use fans to do mitate effects?

- Of course. For example, in the scene where prince Rama’s younger brother goes to the forest where he is exiled to and bring him back to the palace after the king’s death but Rama refuses to return with him. His brother asks Rama to at least let him take Rama’s sandals back to the palace and place them on the throne to show that Rama is the true heir to the throne, we used the fan to symbolize the sandals and that brought a big round of applause. But that was only because we had given a short lecture about mitate before the performance.

- What kind of process was involved in this collaboration?

- I wrote several scenes and then sent the script from Japan to India and had the people there translate it and compose music for it. The music was composed for tabla and sitar, and it was amazing how closely it matched the give-and-take of the drum (taiko) and flute (fue) of our Japanese Hogaku accompaniment. In the stage script I wrote which parts would be Indian music and which would be Hogaku music. As with when we have music written for us for a new work in Japan, I noted that I wanted music for a part that would be, say, 3 min. 30 sec. long and what kind of dance it would be, or 2 and a half min. long for such-and-such type of dance. I choreographed most of the dance in Japan. Then we set the music to it when we got to India. At first there was some disturbing uncertainty among the musicians, but in the end it was amazing how well it all came together.

- So, as with Nobunaga, this was another case where you found that, even with different kinds of dance, it would come together if you stuck to the classical traditions, was it?

- In the end, I think the human mind works the same whether it is Oriental or Occidental. And if the things you want to express are the same, it will be understood even if the means of expression are different. Even if the technique is different, I believe that if the mental substance is the same, it will communicate.

However, it is difficult to communicate something through dance, to some degree, if the audience doesn’t understand the story that is being told. So, in those cases we use devices such as using film or subtitles to explain necessary elements about the dance. For the performances of Nobunaga in Russia, and for the homecoming performances of Ramayana in Japan, we used explanatory subtitles of this type during the changing of scenes. I feel that such means have good potential for helping audiences to understand Nihon Buyo. - The unique character of Nihon Buyo Suodori to have one dancer acting out several role in a story, much like contemporary theater, and the freedom of being able to use the fan in mitate to take the place of a variety of props, can make Nihon Buyo an art that includes a very contemporary aspect. And it seems to me that, conversely, it is we the Japanese audience that have forgotten this way of enjoying and seeing its devices as an art form.

- What I want to say to the audience is please give free range to your imagination and let what is taking place in the stage take shape freely in your mind as you watch. It is only when you do that that the story, the work becomes complete. The art of Nihon Buyo becomes complete only through the creative imagination and presence of not only the dancer but of the audience as well.

Rankoh Fujima

The world of Rankoh Fujima

Pioneer of the realm of Suodori

Photo: Kishin Shinoyama

Rankoh Fujima

Rankoh Fujima (b. 1962) was born into a family of master artists of Nihon Buyo (Japanese traditional dance) that dates back to the Edo Period (1603 – 1868). He studied under his mother, the Nihon Buyo artist Rankei Fujima, who attained the title of Living National Treasure. In his role as successor to this family, Rankoh is promoting the succession and spread of Nihon Buyo, while also active as a choreographer, stage director and writer of new works based on stories old and new from all corners and uses them as the subjects for new dance compositions. He is known for his collaborations with other dance genres such as ballet and tap dance. Rankoh is also known for his highly acclaimed original work Nobunaga (premiered 2015, with numerous re-stagings, including six performances in Russia in January 2019), in which he performed with the Russian ballet dancer Farukh Ruzimatov and Japan’s Morihiro Iwata. In 2009 he formed the Goyokai group of five Nihon Buyo artists from different schools.

Interviewer: Sae Okami, Buyo critic

Mai and Odori (yo) (both meaning dance)

Mai is a word for dance based primarily in the motion of rotating or turning around and around, and it is a word with ancient roots also associated with nobility of character. In contrast, odori (also pronounced yo as in buyo) is a word for dance base primarily in the motion of jumping and is used increasingly for dances of modern origins and is associated with the character of the common people.

Goyokai

The Goyokai group of five Nihon Buyo artists of different schools, including Nishikawa Minosuke, Hanayagi Juraku, Hanayagi Motoi, Fujima Rankoh and Yamamura Tomogoro came together as a group in 2009. Their diverse schools dance performance include Kabuki buyo, Sosaku (creative) buyo, Kamigata mai classics and Shinsaku (new works), and this diversity of Nihon Buyo style they bring together adds a depth and breadth of appeal to their performance activities.

https://www.goyokai.com

Magakami

Photo: Masao Okamura

Adayojin

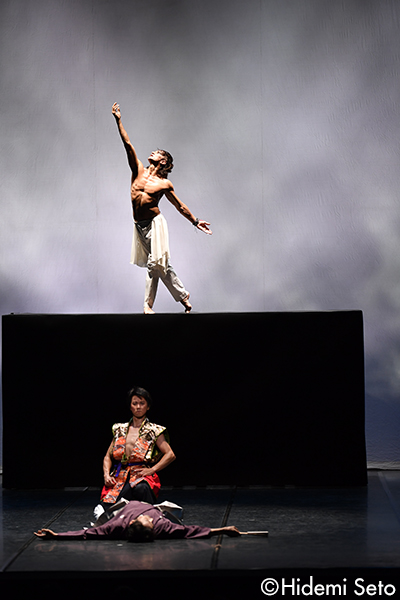

Nobunaga – NOBUNAGA

This dance theater work based on the life of the famous warlord of Japan’s Warring States period, Oda Nobunaga (1534-82) is a collaborative work bringing together ballet and Nihon Buyo. Dancing the role of Nobunaga was Farukh Ruzimatov (former Marinsky Ballet principal and Artistic Director of the Mikhailovsky Ballet Company), dancing the role of Toyotomi Hideyoshi was Morihiro Iwata (former first soloist of the Bolshoi Ballet, and Artistic Director of the Buryat State Ballet), and dancing the two roles of Saito Dosan and Akechi Mitsuhide was Fujima Rankoh. The choreography was by Fujima Rankoh for the Nihon Buyo scenes and Iwata for the ballet scenes. The stage script and direction were by Fujima Rankoh, music composition and lyrics by Umeya Tomoe and Nakagawa Toshiyu. The work premiered in Tokyo in 2015 as “Deai Nobunaga – NOBUNAGA” and was re-staged under new direction in 2017 as “Nobunaga – NOBUNAGA” and toured three Russian cities in January of 2019 as “Nobunaga – Samurai.”

Photo: Hidemi Seto

Goyokai in Collaboration with Indian Artists Ramayana

Related Tags