-

You have been the leader of the Jiyu Gekijo (Theatre Libre) (changed its name later to On-Theater Jiyu Gekijo.; 1966-1996) that led Japan’s small-theater movement and produced many talented theater people since its founding in the 1960s, and you have been active as a writer, director and actor. You were also involved from the planning stage in the Bunkamura culture facility that opened in the Shibuya district of Tokyo in 1989 and served as its first artistic director of the Theater Cocoon. And in 2003, you were chosen to serve as the artistic and facility director of the “Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre” in Nagano Prefecture from 2003. In these ways, you have always been at the forefront of your profession.

Especially important in your work since the 1990s is the fact that you became the first contemporary theater director to direct Kabuki actors with the “Heisei Nakamura-ya” productions of the Bunkamura Cocoon Kabuki series. This was a revolutionary development that freed Kabuki from the traditional conventions of its staging and re-thought the staging from a contemporary perspective. I would like to take this as a starting point and ask you how it happened that you came to do the “Cocoon Kabuki” at Theater Cocoon, which is not a specialized Kabuki theater by any means. -

When I was artistic director of Theater Cocoon, Nobuyuki Onuma of Shochiku [the company that owns kabuki production rights] came to me and asked if it would be possible to do a Kabuki production at our theater. At that time I thought he had in mind the kind of Kabuki productions that had formerly been mounted at the then x Toyoko Theater (1943-71) in the same Shibuya district of Tokyo, in which case I thought it would not really be suitable for our theater.

In fact, since I was young I had been interested in the idea that the small Kabuki theaters ( Kabuki koya ) we see in old paintings and books represented a completely different kind of theater space from that which became established in the West in the modern period. Theater Cocoon is a modern ferro-concrete theater building but when we were designing it, I had in mind elements that were similar to the old Kabuki theaters and I talked at length with the architects about the possibilities of introducing such elements.

The modern theater is designed so that the audience can sit back and quietly watch the finished production that is presented on the stage, and the ideal is that the stage be equally visible from all the seats in the theater. However, the small Kabuki koya theaters were spaces that put the audience together and also gave them a good view each other. That kind of atmosphere created interaction between the members of the audience that might result in fights sometimes or comments about some good-looking woman across the way. And it was a good atmosphere for the audience to enjoy the breaks between acts. So, at the design meetings with the architects I brought up the idea that we consider the merits of that kind of theater environment once again.

Shochiku’s Mr. Onuma may have gotten word of these aspects of Theater Cocoon. So, I thought that if that was the kind of effect they were after, I would be glad to work with them. Then I immediately thought of Kankuro (now Kanzaburo XVIII) Nakamura, who at the time was doing performances in the old Edo Period Kanamaru-za theater in Shikoku, and I went to talk with him abut it. When we met he happily showed me around the backstage area of Kanamaru-za theater. He had come to see my production of Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera at Theater Cocoon and looked around the theater at that time. So, I thought that this was a person I could work with, a person with a similar orientation. That is how we came to work together.

It may seem that Brecht is completely different from Kabuki, but there are similarities in the aim of becoming one with the audience and going beyond the purely intellectual aspects to create theater that goes back and forth between the stage and the audience area and the kind of koya (small theater space) that makes that interplay easier to achieve. - Kanzaburo writes in his book that he was deeply impressed and moved when he saw the tent performances of the Juro Kara’s Jokyo Gekijo company when he was in high school in the 1970s. The almost bawdy, energetically charged theatrical space he saw there made him think that early Kabuki must have been like that and that someday he would like to do that kind of Kabuki. He says that is the idea that led to the new Theater Cocoon Kabuki. In that sense, you can say that Kanzaburo had the desire to come closer to contemporary theater, while I think that you had the desire to approach Kabuki from the standpoint of contemporary theater. I feel that those two desires came together in a very fortunate union.

- Yes. The fact that a person like Kanzaburo has emerged from the Kabuki world and the fact that in the past Kabuki actors have acted in contemporary theater indicate that there are some parts of the traditional techniques of Kabuki that must be used in the staging of Kabuki and some that may not be necessary. For that reason it may be possible for the boundaries between Kabuki and contemporary theater can be skillfully broken down. It will not be easy, however.

- Traditionally there is no such thing as a director in Kabuki, and the necessary decisions are made by the leading actor, known as the zagashira . And, while there are times that a director will be involved in productions of New Kabuki, they don’t really change the traditional Kabuki style. In that sense, it was really a revolutionary thing when you first directed Kabuki. Did you encounter any resistance from any of the actors?

-

In that point, Kanzaburo acted as a buffer for me and told the other actors, “Let’s do as the director says.” Of course, I believe that there still must be some reluctance and conflict. If you think about it, it can’t be easy for people to change things that they have been seeing since they were children. For instance, if you are suddenly told to write with your left hand instead of your right, it may be an interesting thought, but your left hand just doesn’t know how to move that way (laughs). That is how deeply the style is set in their bodies.

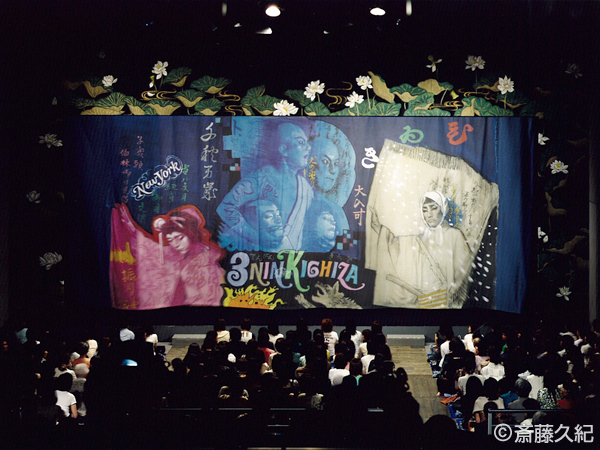

So, it is easier to do things from the Kabuki repertoire that aren’t performed that frequently, like Sakura Hime or Kamikakete Sango Taisetsu , but ones that are performed often like Sannin Kichisa the lines and actions come out almost automatically and the bodies naturally take the same positions. I’m sure it is really hard for Kabuki actors trying to change things that deeply engrained in their bodies. - When you direct Kabuki, what is your approach?

-

First, I read the original and try to imagine the atmosphere that is behind the story, so that I can begin to get an interpretation of my own. Then I make proposals about the psychological orientation of the characters in the story. For example, in

Sannin Kichisa

(The Three Kichisa) I proposed that the Obo Kichisa (young ronin Kichisa) is the son of a respectable samurai, and although he tries his best to act like a bad guy, he has never killed a person yet and, in fact, inside he is actually scared. Based on that idea, in the scene where Denkichi tries to get back big sum of stolen money from Obo Kichisa and threatens him with the blustering words, “I used to be a hoodlum,” as he draws near, I had Obo Kichisa jump back in fear and bump into a wall. After that, when Obo Kichisa finally kills Denkichi with his sword, I had him gasping for breath. It is an unseemly, un-heroic image he presents. In Kabuki, it seems to be a rule that they never let the

nimaime

(handsome young romantic lead actor) show such an un-cool self. In every play the

nimaime

has to always appear cool and nonchalant. How can you have him gasping for breath! (Laughs) But to me the gasping man is more appealing, and it is easier to identify with such a character who may have just killed for the first time, don’t you think?

Another thing I do is to try to do is present devices that would surely have delighted anyone back in the Edo Period—be it the playwrights Mokuami or Nanboku or the audience—if a [director] like me had been living then. For example, in the scene where the testimony paper is burned, a drawing picture of flame on the end of a stick is brought near the paper and at the moment the flame touches the paper it is flipped to the back side, which is painted with a picture of a burning paper. When I ask Kanzaburo if an idea like that doesn’t sound Kabuki-ish, he says it is and likes the idea. But it is the kind of idea that seems like it had been used since the Edo Period, so the audience doesn’t realize that it is actually a new device (laughs).

For Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan–Kita version I used about twenty actors dressed in sea blue to portray the water of a moat and had them swat their bodies to get the effect of waves on the water. This isn’t something that they do at the Kabuki-za, but don’t you think it is the kind of device that the people in the Edo Period might have thought of? It is the kind of thing that they do in mass-game events, so it isn’t really strange that people would be used to portray the effect of water in a moat.

In the end, what I think I am trying to do in directing Kabuki is not to read all the literature and become a Kabuki otaku but to propose things based on my own theater experience that I think will be enjoyable. - One thing that surprised me was that the innovative things you did early on in your Kabuki productions, like giving the characters more reality as human beings, were not well received by many people who knew Kabuki, especially the theater critics. I am not really familiar with Kabuki, so it seemed to me that people should appreciate the positive aspects of the new things you were doing but instead they stressed the negative and it made me feel that their outlook was rather narrow-minded.

- I think that being unfamiliar, being less than an expert, is very important if you are going to try to do something new. I tend to go into things without specialized knowledge, and I make it a point not to acquire more knowledge than I need to execute my idea. I try to keep myself ignorant of specialized knowledge. If you don’t, you end up making it a play that tries to show off all your knowledge. We are creators, and there is a range of knowledge that it is better for creators not to know. And there are cases where, even if you do have certain knowledge, it is better to hide the fact that you do. What’s more, people who are used to watching Kabuki often talk about the kata (forms of the Kabuki acting), but in the Edo Period those forms were probably not as standardized and stylized as they are today. Especially in the late Edo Period when actors like Ichikawa Kodanji IV were working with Mokuami, there was probably a lot of realism to the plays and the acting. If you think about it, they were doing new works, newly written plays all the time, and in a new play there are no kata , so the actors would have to rely on their own feelings and thoughts to develop a character’s actions. In a scene of anger and frustration they would bite on a towel or a sleeve hard and pull on it as a gesture of frustration, but by the time of the original actor’s great grandson, it would not be a question of what to bite on but you would already have it formalized into specific kata like, “Your great grandfather used to bite on this portion of the sleeve.” So, when I propose new psychological elements in the characters, it is not necessarily just with the aim of doing something new but, rather, it is an attempt to read back into the play some of the things that have been forgotten during this period when things were being transformed into predetermined kata .

- In the Cocoon Kabuki you have replaces the seats the front half of the audience area with a flat platform to create traditional floor seating. What is the aim of this?

- In regular theater seats where there is likely to be a stranger in the next seat, you are refrain from turning around to watch when the actors have come out into the aisle behind you. But with a flat sitting area, the audience have more freedom to turn their bodies around this way and that when the actors come out into the seating area. In that sense, sitting on floor pillows ( zabuton ) is more convenient than seats with a backrest, and I also wanted to add some of the aspects of the old Edo period Kabuki theaters, where people would sit on zabuton and spread out their box lunches to eat while they watched the plays. But, today’s young people aren’t used to sitting on the floor, so we actually find that the regular seats in the back half of the theater sell out before the platform seats (laughs). It’s a bit disappointing really.

- In the Cocoon Kabuki you don’t have a traditional Kabuki theater hanamichi (raised runway through the audience area for actor entrances and exists) so the actors come down through the aisle and then directly onto the flat platform seating area. The audience really seems to appreciate this, but what is the reaction of the actors?

- They seem to enjoy it. In the Kabuki-za today the hanamichi is a sacred space like the stage itself that cannot be violated, but I believe that in the old days it was probably a much more freely-defined thing that involved going in and out of the audience seating area. I believe that there was more of a sense of going from this side into your own world and going from your world into this other side.

- Your friend from the Jiyu Gekijo days, the actor Takashi Sasano, appears in both Cocoon Kabuki and the Heisei Nakamura-za productions. At the beginning it seems that there was a lot of objection to this, but know he has become such a familiar part of the production that today the audience calls out to him in Kabuki style with a yago (name the audience calls Kabuki actors by during the performance as a form of salute), in his case “Awaji-ya” after his native Awaji, Hyogo prefecture.

- At first it was just a small part. In Kamikakete Sango Taisetsu there is a pauper who comes out at one point in the play and all he says is “Masu masu, masu masu.” It is a part that has no real consequence in the story and it is usually cut from the Kabuki productions, but I felt that it was a waste to cut out such a fun character. However, I was told that there were no Kabuki actors today who do that part, so I asked Sasano to do it. Then it happened that one of the Kabuki actors in the production with a bigger part got sick, and Kanzaburo asked Sasano if he wanted to try the part, saying, “I bet you can do it.” That’s how it happened.

- Your own designs for the stage art also include things so revolutionary that no one would think they were for a Kabuki set. I imagine that these are designs that have resulted from the unique characteristics of the Theater Cocoon space, but how did you come up with the ideas?

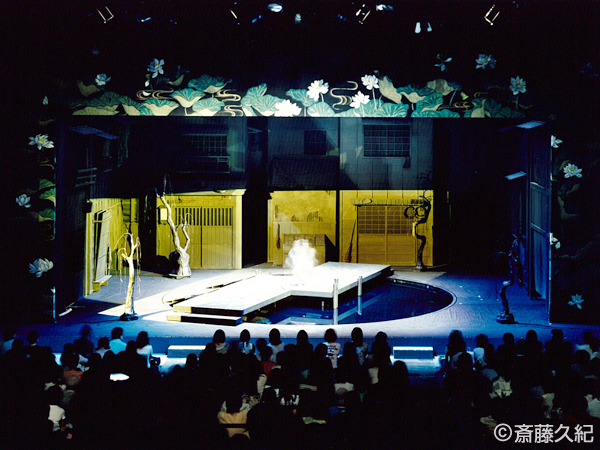

- One thing that I think can be said—and this is not limited to the sets—is that there are many interesting things used in Kabuki, they tend to be just lined up with little consciousness, so full advantage is not taken of their unique qualities. For example, the traditional Kabuki sets tend to be flat in nature, but they have the fascinating effect of at times making the 3-dimensional actors appear 2-dimensional, but that effect is not consciously taken advantage of in the plays. For that reason people feel that the lighting could be used more effectively to create shadow, and not only the horizontal but also the vertical movement could be taken into more consideration. In this way, the good aspects of Kabuki sets are being negated to the extent that it is a waste. My designs are based on this feeling that more respect should be given to the good points of Kabuki sets.

- What about the stage lighting?

- The lighting used in Kabuki today is the electric lighting that was adopted in the Meiji Period (late 19th century) and the lighting used was up until then was discarded at that time. In the Edo Period candles were used for lighting, so there was surely darkness and shadows on the stage. The people of that period were used to the darkness of candlelight in their daily life and they watched the plays with the same kind of peering into darkness to see everything that they could. But when electric lighting was first introduced in the Meiji Period, on one knew how to use the lights and they ended up just giving the stage even, flat lighting across the whole stage. Entering the Meiji Period the flat seating platform was changed to chairs and the lighting was changed to bright electric lighting, but for some reason everything stopped there and hasn’t changed since. When you think about it in this way, you might say that I am just feeling natural doubts about why time suddenly stopped for Kabuki. It is not my idea to try to make Kabuki modern or change it but, rather, I think I am looking at Kabuki with the feeling that it was actually quite different originally from what it is now and that the Kabuki people of old would gladly have used some of the tools available today if they had had access to them at the time.

- When you did your first Kabuki production of Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami , you covered the stage with a layer of soil and surrounded it with the kind of straw mats used to make a vendor’s stall at a festival grounds and it created the atmosphere of watching the play in a temporary festival shack.

- I often tell people that my first theater experience and my original image of theater was seeing a play in just such a makeshift shack theater when I was three years old in the countryside where I was evacuated during the War. I had been sent to a place near the city of Shinjo in Yamagata Prefecture for about a half a year near the end of the War and the farmers there took me to the play. I don’t know whether it was a rural Kabuki play or a play by a traveling actors troupe, but I can still remember that it was in a makeshift shack with a few naked light bulbs hanging here and they and that the actors were doing pantomime. So, I wanted to do Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami in that image. For the first performance I even tried planting some shepherd’s purse grass on the stage but the trampling of the actors ruined it right away. The dust that rose from the stage during the action got to the actors’ throats and the hems of their kimono got dirty. The actors said they couldn’t stand it, so for the next production the dirt was replaced by a dirt effect using cloth. I still want to do it with real dirt though (laughs).

- For the second production the back of the stage was opened onto the streets of Shibuya and people came in through the opening carrying a festival shrine, and in the end a patrol car was driven in too. I remember thinking how amazing it was to be doing these kinds of things in a Kabuki play. I believe that only an artistic director who knew his theater completely could have done such things.

- That is the theater’s receiving bay, and I had insisted strongly during the planning of the building that the architects make it so that the receiving bay open directly into the middle of the back wall of the stage. The architects had asked why I was so concerned about the location of the receiving bay and told me that I was overstepping my bounds to insist on a thing like that. But I kept insisting that it come in the center of the stage. I knew that some day it would be useful (laughs). I also asked that the air-conditioning system be designed so that it could be used effectively when filling the stage with smoke effects, and at that time also the architects were asking why an artistic director is making demands about the air-conditioning system (laughs). There are lots of secret devices like this in Theater Cocoon.

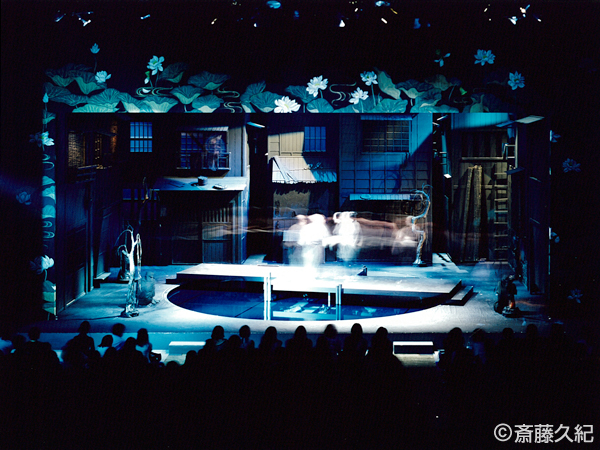

- For the set of Sannin Kichisa you created a round pool of water about seven meters in diameter in the middle of the stage with a bridge across it. What’s more, you took the unprecedented step of making it so that the pool and bridge could revolve during certain scenes.

- Sannin Kichisa (The Three Kichisa) is a play where the riverside setting is particularly important. Edo was a city of waterways and I thought that it would be interesting to have numerous riverside scenes. But having to take time out to change the scenery for each scene would detract from the interest of the play as a whole. So, even though I knew that it would be odd to have a round river, I thought it would be forgivable if a simple revolving of the pool and bridge enabled a variety of quick scene changes. I also thought that it would be nice if we could get some beautiful effects by reflecting light off the water surface.

- One of the unexpected things you did was to have the Ojo Kichisa (the young pickpocket Kichisa who dresses like a lady) deliver his famous line about the moon and the misty spring sky from atop the revolving bridge and pool and have him begin the line while facing the back of the stage and end when the bridge has turned 180 degrees and he is facing the audience. The actor must have had a very difficult time with that scene.

-

Now he is especially proud of that delivery whenever it is performed, but apparently at first he thought I had really gone overboard on that scene (laughs). But, although they deliver that line facing the audience in the regular Kabuki performances, there apparently were doubts about where the moon should be in the past. The scenery is painted on the back wall of the stage and the moon is painted there too, so why should that line be delivered facing the audience instead of facing the moon? It is said that there was an actor seeking a higher level of realism in the Meiji Period who said that the moon must be reflected in the water, so he decided to deliver the line looking down into the water (laughs). So, it is interesting to realize that the people in old days also struggled with these problems.

There are many anecdotes like this in the Kabuki world. For example, in the past they used a real dog in the monkey scene in Sannin Kichisa until Kikugoro the 5th or 6th once used a real monkey. He tried to do something new by using a monkey in the monkey encounter scene, and apparently things had gone well in the rehearsals, but on opening night the monkey ran off into the audience—probably because the people there had their food spread out and were eating—so they had to cancel the monkey appearance after the first performance. The people of old were always trying new things, it seems. - In the climax scene in a snowfield you have an electric guitar playing the sound of the wind and Ojo Kichisa stands in this field of complete white in a bright red kimono. When the three Kichisa, Osho Kichisa, Obo Kichisa and Ojo Kichisa have committed suicide by killing each other and the three bodies lie on the ground with snow falling on them, the music is a lullaby written and sung by a rock singer, Ringo Shiina. I was very surprised and impressed how well Shiina’s song and the electric guitar blended together.

-

At the premiere six years ago, we used a tape recording of actual wind. In Kabuki, the sound of wind and the sound of snow falling is traditionally represented with a “den den den den den” sound made on a drum, but I proposed using real wind sound. Even at the time, however, I had doubts about whether that was the right thing to do, but now I have gone even farther by using an electric guitar. That’s how much things have changed with me in these six years, and it makes me think.

In Kabuki, when there is an important line in which the actor is about to reveal the truth about something that happened several years earlier, there is a particular shamisen sound known as an aikata that is always made on the shamisen to punctuate the moment. In this latest production of Sannin Kichisa I used the electric guitar not on for the wind but for that aikata sound too. But, when you use the shamisen, that sets the timing of the delivery and you can’t pick up the tempo of the delivery even if you want to. They suggested that if I wanted a faster paced delivery they could remove the shamisen aikata , but I suggested that instead of removing the aikata , we could change it to a different sound and I played them a tape of an electric guitar sound. When Kanzaburo heard it he said it sounded OK. That is how we came to use it combination with the wind-sound guitar part. - By the way, you began directing the Cocoon Kabuki from the second production, Natsumatsuri . How is it that you didn’t direct Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan , which was the first production of the Cocoon Kabuki series?

-

At first I participated in the ambiguous role as artistic director. At the time I thought that I could never direct a Kabuki production, that it was sacred ground I dare not desecrate. At the same time, however, I had the feeling that a partial, unclear sort of role was also not a good thing. If I was going to be involved, I should be involved completely, with full responsibility.

I still have the feeling somewhere in the back of my mind that I should not be directing Kabuki, that I may be breaking down something that shouldn’t be broken down. I still have this inexplicable sense of uncertainty. If things go on like this to the point where we are using rock music and the costuming get to the point where anything is allowed, what will remain to call it Kabuki? I believe that we constantly have to be thinking about what we will be losing in the process.

For example, with cell phones and computers, we gladly use them because they are convenient but we may suddenly realize at some time that by using them we have lost something that was equally important and it is too late to recover them. But I don’t know what is being lost, so I believe that I just have to keep going. I sometimes try vainly to take it on myself to find out what we are losing by going to the Kabuki-za, but I still don’t know. So, I wonder if the essence that was once there hasn’t already been lost. - I would like to backtrack a bit to 2000, when the Heisei Nakamura-za was launched in a temporary theater constructed on the banks of the Sumida River in Tokyo with a performance of Hokaibo . What was the idea behind that move?

- That was a realization of Kanzaburo’s idea of recreating the original form of Kabuki. His obsession with this idea moved a lot of people. On the opening day the Chairman of Shochiku was there to pat Kanzaburo on the shoulder and say, “You do your ancestors proud.” I believe that there are a lot of things he has in mind and feelings that are hard for us to know, such as the fact that Kanzaburo’s (Kankuro at the time) ancestors were the heads of the Nakamura-za Kabuki koya in the Edo Period.

- Then he went to New York in 2004 and set up a Heisei Nakamura-za temporary theater in the square in front of the Lincoln Center and put on a production of Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami . I didn’t see it myself, but they say that it was a great success.

- Yes. People with no preconceptions about Kabuki, people with no ideas about how Kabuki has to be, were watching it, so they were able to appreciate it with the same perspective as watching contemporary theater or Shakespeare. The reviews also treated as any other play, talking about the story, the intentions of the staging and direction, and, not knowing that Sasano was not a Kabuki actor, they called him “great actor.” So, I felt that it was a good thing to show it to people who could watch it as theater with no preconceptions.

- From July 10 of this year, a Heisei Nakamura-za production of Hokaibo is scheduled to be performed at the Lincoln Center. This is a work that you directed at the Tokyo Kabuki-za in 2005. For that production it was very interesting the way you set up audience seats on either side of the stage and filled them with dummies and a few real people. Was that an attempt to re-create the atmosphere of the theater koya of old?

-

Actually, ideas like this come from an archive of things I have thought about over the years. Once long ago I went to see a performance of Mozart’s

The Magic Flute

and I had the idea at that time that it would be scary if the people in the audience seats actually turned out to be dummies. Once when I went to the Haiyu-za Theater to see a “New Theater” play as a middle school student, all the people in the audience around me were strangers and adults and I became really scared when I thought that maybe all of these people are serious drama enthusiasts and perhaps even actors in the play themselves and that I was the only one who wasn’t a part of the play (laughs). I have had these kinds of common experiences in the back of my mind for all these years, and that is why I decided to put dummies in those seats in

Hokaibo

. Also, I wanted to remind people once again that everyone in the audience is actually being seen by the other people in the audience. What’s more, I wanted to do something to narrow that very wide stage at the Kabuki-za, and I also had in mind the fact that in the Edo Period theaters there were seats off to the side of the stage that were the cheapest seats of all.

Hokaibo is a unique work in the Kabuki repertoire. The main character is a beggar priest who appears as a peripheral character in a family feud, and he is a kind of objective observer who refers to himself in the third person. In the Lincoln Center production I want to have all of those comedy lines delivered in English. - By the way, in you contemporary theater productions you also appear as an actor. Have you ever thought that you would like to act in one of your Kabuki productions?

- There are some parts where I feel that an actor like Sasano is necessary to make the part work but I don’t have an actor to fill the part, but I feel that I still need to be watching the play objectively from the audience side. If it weren’t for that, I would prefer to be watching the audience from up on the stage. But for now, Kanzaburo is serving that function for me. In New York, however, I am thinking of appearing as a kuroko (on-stage assistant wearing black clothes and hood for anonymity). I hope you will look forward to seeking what kind of kuroko I come out as.

-

Since you began directing the Cocoon Kabuki and the Heisei Nakamura-za, I believe that those developments have set the stage for the Kabuki world to accept talent from the contemporary theater world.

I believe that Hideki Noda’s writing and directing Togitatsu no Utare and Noda-ban Nezumi Kozo as well as Yukio Ninagawa ’s directing of a Kabuki version of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night were all made possible because of your achievements. - I believe that these were all developments that should have happened in the first place. It is good for people like Noda to write things like that as literature and it was good when Ninagawa did a Kabuki version of Shakespeare. And I think things will become even more interesting when other directors do different versions of the works I have done using different Kabuki actors.

- You mean in the same way that various directors do different versions of Shakespeare’s plays?

- Yes. That will bring an even higher level of artistic tension and stimulate other Kabuki actors. I think that such a period is definitely coming.

- Can Molière and Brecht also be done in Kabuki versions?

-

I think they can. There are plenty of actors in the Kabuki world. And if that happens, the repertoire will become more interesting. Recently I saw a Black Tent Theater production that set Brecht’s

Mother Courage and Her Children

in the context of a battlefield during Japan’s 16th century Period of Warring States. It was the kind of play that could be re-staged as a Kabuki play almost exactly as it is and I believe it would be quite interesting.

A play like Ren Saito’s Cusco that we did at On-Theater Jiyu Gekijo could also be done as a Kabuki play.

Another interesting thing that can be done is for non-Kabuki actors and to do plays from the Kabuki repertoire. We are now planning to do a production of Sakura Hime directed by myself that would be performed as a Kabuki play and then as a contemporary theater play in alternate months. I think that plan will be realized the year after next. - That sounds extremely interesting. In the contemporary theater version would Sakura princess by played by a woman?

- In the Kabuki version a male onnagata actor will play her and in the contemporary theater version a female actress will. I believe that the interpretation of the play will change when it is done as a contemporary theater play as compared to Kabuki production. And that may involve some misinterpretation, but that is the area I would like to pursue.

- You are currently serving as artistic director and administrative director of the Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre. Your activities there have included the highly acclaimed production of The Caucasian Chalk Circle resulting from three years of workshops and performing it in an improvised outdoor amphitheater style stage created in the indoor theater rather than using the existing audience seating. I would like to conclude this interview by asking you about your work there. I believe there are very few people in Japan who have experienced serving as both a private-sector commercial theater’s artistic director and a public theater’s artistic director. Having done both now what is you impression?

-

There have been many surprises and many interesting things. As I look back now and think about why I accepted the position, first of all, when we opened the underground theater Jiyu Gekijo in Roppongi, it was in the days before we even had the title artistic director and I think that during those years I always wished that the small space we had there was a proper theater. That is why I had the desire to move to Theater Cocoon when I got that offer and why I eventually took the offer from Matsumoto too. Later I realized that my feelings in that area had always been consistent.

My feeling was that a theater is not just a box where plays are made but that a theater exists because there are people there, and my fundamental feeling was always that because it is there it should be used to exert some kind of influence. That is why I believe I always had an interest in theaters.

When I was at Theater Cocoon, the [Bunkamura] corporate people were always worrying about what the stockholders and the company thought, and now that I am at the public theater [in Matsumoto] it is a case of thinking about what the public at large thinks. In the case of the Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre there was an opposition movement during the planning stage about using such a large amount of tax money to build the theater facility. And since I went there, I learned a lot in the first year about how much I should become involved in the political aspects and what the causes of the controversy had been. It is not a case where I am the one who is defending the public theater. I want to hear the opposing opinions because they are interesting, and there were many things that I felt were well based. And, rather than simply not listening, I think that the best relationship is one where there is opposition, debate and finally one side admitting that the other has a good point. There are a number of issues involved in how to best use tax money and I am now making efforts daily to convince people in that area. - In the case of public theaters in Japan, one of the things that has to be done is for the government to make a connection to the people and another thing is to create the kind of high-quality productions that can be shown to the world with pride. I would imagine that it is very difficult to achieve both of those aims, and I would like to ask you what you are doing in those areas.

-

That is something that I have had in mind from the beginning, and I would say that it is very difficult problem to divide works into things that the citizens will accept, things that are for the popular audience and things that are avant-garde. The other day I had a debate with the artistic director of another public theater who said that avant-garde work is no good for regional audiences. That made me angry and I asked him what avant-garde is. For example, the butoh group Dairakudakan was active in Omachi city in Nagano Prefecture and the farmers from that area came to see their performances. One of [butoh dancer] Kazuo Ono’s students is active in Matsumoto, where his day job is running a bar, but then he whitewashes his body and puts on a

samurai

hairstyle and goes out on the street to dance. When he does that children gather to watch, and when he makes threatening gestures they get scared and run away, which I thought was very healthy. This is a case where there is a solid relationship between the performer and the audience. No matter how many people you gather in Tokyo who talk knowingly about butoh and can tell you what school a performer is from, I don’t think it is really established successfully as a form of expression with that kind of performer-audience relationship.

These are the things I am thinking about as I do my best to try and create once again a sense of value in theater and create works that people will think are truly interesting. In fact, right now I am thinking about creating a theater company connected with the Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre and we are preparing to launch the company next year. The core of the company will be my former students from the Nihon University Arts Dept. who have moved to Matsumoto. There are already five who have moved there.

Recently, the professional actress Atsumi Hiraguri joined them for an experimental performance at Russia’s Alexander Vampilov, and at that time they made flyers saying that they were creating a theater company in Matsumoto and asking people to join in and distributed them to the audience. That stirred up a lot of interest and people told them that they would take some of the leaflets back to their offices to distribute. The entrance fee had been set at 1,000, but an amazingly large number of people turned out for the performance.

Before that we did a test performance of a work based on the Grimm Fairytales where there was no entrance fee and many families came, which was a response that I thought was very good. Of course it is no good if they try to do something too difficult from the beginning. It is better to start out by building a relationship with people who at first tell them that they are still green and bring them rice balls to eat because they are sure that the players are too poor to have enough to eat and cheer them on saying, “Eat this and try harder to do a good play next time.”

So, rather than saying that high-level works won’t be well received or dismissing the mass audience as a low-level one, we should be listening once again to the audience as we work and proceed within that relationship. I believe that there is great potential in having everyone growing as they help a young theater company grow in an interactive relationship. - We see more and more public theaters working together in tie-up relationships. What do you think of this?

- It is a method that should be pursued, but I feel that there is a danger of the projects failing if it is done from the attitude that it is more convenient or because more money moves that way. Also, it runs against my temperament to work with someone I have never met before simply because they are part of an organization. I can understand if it is a case where two people who think the same way work together and eventually that two becomes five and then ten, but I don’t trust a project that comes out of an organization of people who don’t share a common sense of what their goals are.

- In Matsumoto there is the classical music festival “Saito Kinen Festival Matsumoto” that is organized by people including [conductor] Seiji Ozawa. Do you have any ideas about perhaps creating a theater festival?

- The Saito Kinen Festival is run on a program of alternating years of opera and non-opera programs, and there has been talk of making the non-opera years more drama-oriented. I think it would be good if things gradually evolve in that direction.

- When I listen to you talk, it seems to me that your ideas about theater haven’t changed much since your Jiyu Gekijo days.

-

It is not something that I am conscious of, but I feel that when I watch theater, whether it is Kabuki of Brecht, I can see that aspect. When I was first training as an actor at the Haiyu-za, there was an incredible director named Koreya Senda. One night when I returned to the studio to get something I had forgotten, I looked in the studio and saw Mr. Senda there all alone painting a large cow’s-head mask. I remember thinking what a cool person he was. More than his reputation or achievements as a director, I thought that that image of the man was great.

When I was at the Bungaku-za for a little over a year, there was an actress named Haruko Sugimura. She was a great actress, but there was one time when we did a performance in one of the regional cities and when the performance was over and the actors took their bows and the curtain came down, she bowed once more to the back of the curtain. That was another time when I thought, “This is an incredible person.” I remember thinking that everyone was foolish for not seeing her bowing, for not seeing that important lesson. I can’t say that I have really learned a lot over the years, but I will never forget the image of the back of Haruko Sugimura bowing at the curtain when no one was watching and Senda painting the cow mask all alone at night. I believe it was because they loved and enjoyed their work so much. And I think that Kabuki must be that kind of thing too.

But there is an enjoyment that is not an internalized but projected outward. I’m going to take audience aback, or I’m going to make them happy. Something in it that is not just smiling, there is also anger and sadness. I think it is sharing those things with a group of fellow theater people that is the true enjoyment. In the case of Sannin Kichisa , I think it is a play that author Mokuami wrote with the desire to make a big hit, but as he also writing it, there was probably also a secret knowledge at the tip of his pen that there would be people who will feel an affinity for these petty hoodlums even though they know that they will eventually be plucked out of society.

Kushida Gijo

BRONZE Publishing Inc.

2,100 yen (tax in)

ISBN: 4-89309-418-1