The Encounter with Theater

- You established the company OiBokkeShi with the purpose of pursuing your theme of “Aging and Theater,” and you are now conducting theater activities with the now over 90-year-old Tadao Okada (nickname: Oka-jii). At the same time you do workshops around the country teaching caregivers for the senility-inflicted how to use theater methods in their work. We are told that you phrase the concept behind these workshops as “bringing the knowledge of theater to care-giving, bringing the depth of caregiving knowledge to theater studio.” Could we begin by having you tell us about the status of your current activities?

-

In the “Aging and Theater Workshops” we have been doing since 2014, the workshop participants take turns playing the role of a senile person and the role of a caregiver, and the aim is not to alleviate senility but to experience communication based on accepting senility. Caregiving has the bad image of being a 3-K job (

Kitsui

(hard),

Kitanai

(dirty) and

Kyuryo ga yasui

(low wage), but in fact but we believe it is also a job that can be very creative and rewarding. While making theater as an actor, I also worked part-time as a care-giver, and it wasn’t long after I started the care-giving work that I began to feel that theater and care-giving were vocations that went well together in many aspects. And my wish now is to have people experience those creative aspects the two share through our Aging and Theater Workshops. In 2016, I received an offer to serve as Art Design Director for the town of Nagicho in Okayama Prefecture and in that role I began conducting activities to deal with the issues confronting the local community. At community salons we are doing theater workshops with the elderly men and women, but in fact, moving their bodies and using their minds like that is useful from the standpoint of preventative caregiving, and it also leads us all to think about how we should best accept the realities of aging and dementia.These workshops involve two types of activities, with one being caregiving and the other theater, and for the caregiving aspect is not done not only at nursing homes but also we get invitations to hold them at hospitals and schools where caregivers are taught and from local government agencies that organize lectures for local citizens. For the theater aspect, many of the requests for us to hold workshops come from public theaters as an outreach program activity to help bring arts and culture into the lives of local citizens. For example, in the case of the Mie Center for the Arts, the Center serves as the coordinator for holding our workshops at nursing homes and homes for the elderly and associations of families with dementia patients. Since my “Aging and Theater” workshops are for people who work with the elderly and in nursing homes and for people in the medical field, and since they are mostly people that seldom if ever go to see theater normally, my hope is that my programs can serve as an opportunity to communicate the positive effects of the arts.At OiBokkeShi, we now have a repertory of three plays, and the people who come to see our performances are not only people who like theater but also people in the care-giving and medical fields who have never been to see theater. For that reason, I believe that our program is also serving to break down the barriers between caregiving and theater.

- Would you tell us how you got involved in theater originally?

- Originally I was interested in film, but my high school only had a drama club, so I joined that, and that was my first encounter with theater. I was the type of person who would always be off by myself reading books during free time, so I never spoke to people much and I was rather ashamed of that characteristic of myself. I was bad at speaking in front of people, so I never intended to become an actor, but I was interested in writing scripts or directing.

In a script that was written by the teacher in charge of our drama club there was one character who was a withdrawn stay-at-home boy who never said a single word in the play, and everyone said that role was perfect for me, so that was how I got on the stage for the first time. And it turned out that people who saw our play told me I had done a great job with that role (laughs). Until that time, I had thought that it was only people who liked to stand out and were good at talking and making people laugh that became actors, but with that experience I discovered that there was also a place for someone like me on the stage. As my entry to theater, I feel that experience was very good. If it hadn’t been for that role as an autistic child, I probably would never have become involved in theater. Then, when I was in my third year in high school I was getting roles that had lines to speak, and it was then that I realized I could speak if it was a role on the stage with lines to deliver (laughs). In short, speaking line on stage turned out to be speech rehabilitation for me. Although I was just delivering the lines written in the script, it became a simulated experience that showed me how much fun talking to people could be. In other words, I learned the enjoyment and interest of speaking with people through theater.Near the end of high school, when I was unable to decide what to study in college, the teacher of our drama club recommended to me that I go to Obirin University where Oriza Hirata taught theater. So, in summer vacation of my third year of high school I went to the Obirin University open campus day and took part in a workshop by Oriza-san for the first time. It was a real eye-opening experience for me! That is when I decided to go to Obirin, and when I did, I studied under Oriza-san and learned a lot from him. From the year 2000, Oriza-san was holding workshops at educational institutions and teaching his own theater method. Also, it was a time when little by little theater makers from Tokyo were beginning to move to regional cities where arts festivals were being started and public theaters being newly opened. So, while I was still at university I was beginning to think about how to connect theater to communities and how to make a living doing theater.- Would you tell us what Oriza-san’s workshop was like that made it such an “eye-opener” for you?

- The workshop I first participated in at the Obirin open campus day was based on the situation where you are in a train and you have to start a conversation with a stranger you don’t know. There was a simple script explaining that in a four-seat box on a train there are two friends A and B sitting having a conversation, and to the box a third passenger C comes in and sits down. Either A or B starts a conversation with the stranger C, asking if he is on a trip. For me, as a shy high school student, I wasn’t able to say even that simple conversation-starter well.

Oriza-san then asked us high school students if we ever spoke to strangers in a situation like that, and most of us said that we didn’t. Then he asked if the stranger were a young mother with a baby and a traveling bag and the baby was showing interest in you, would it be easier to naturally start a conversation by asking her if she was on a trip. If it were a professional actor and he/she had trouble starting the conversation naturally, a director might assume it was a problem with the actor. But Oriza-san said that if the conversation-starter didn’t come out naturally he would start to think if it wasn’t a problem with the environment. It was that idea of Oriza-san’s that changing the environment could make the lines come out more naturally that was the big eye-opener for me. This idea that, even for a person like myself who was too shy to talk to a stranger in a train, changing the environment could enable the acting to become more natural, the idea that it is not a problem of the individual but a problem of the environment is something that can be applied not only to theater but also to many problems of communication. This made me realize how deep the art of theater was. This approach that was used in that workshop had a big influence on me and the work I am doing today.- After studying theater arts at Obirin, what did you do next?

- I worked as an actor on the small-theater scene while doing part-time jobs to support myself, and then in 2010 I joined Oriza-san’s Seinendan theater company. That year, my contract ran out at the company where I was working part-time and I was suddenly out of work. I had just gotten married a little earlier and there I was “unemployed” (wry laugh). Since I had been working part-time to support myself while I pursued my acting career until then, I decided to look for another part-time job and the employment agency I went to told me there were jobs in the caregiving field, so that is the work I started doing.

In 2011, Japan suffered the big disaster of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, and a year after that my father died of cancer. There I was in my late twenties doing theater while working at a part-time job and I realized I had nothing much to show for it, so I felt that I had reached a real turning point in my life. As I thought about my life ahead with my family, I thought that it would be best to move to someplace other than Tokyo and I decided to move to the town of Wake in Okayama Prefecture. I told Oriza-san that I found care-giving an interesting vocation and that I was thinking of quitting my acting work in Tokyo for a while to concentrate on caregiving somewhere in a smaller town. And I told him that eventually I was thinking of doing work that would connect caregiving to theater. I felt that there was something in common between theater and what I felt so enjoyable about work as a care-giver, but it would take some time before I could properly put in words what that “something” was.

The Birth of OiBokkeShi

- About a year after moving to the town of Wake you formed the unit OiBokkeShi in 2014.

-

When I was studying about caregiving I had the opportunity to hear a seminar by the physiotherapist Haruki Miyoshi

(*)

. That is when I clearly felt the real affinity between caregiving and theater. I felt that the skills at work in theater could be of use in the caregiving workplace and the knowledge gained in the caregiving workplace could be put to use in theater to add another layer of depth that would make something that has never been seen before. And I thought that the best way to communicate this to many people was through theater workshops. I had this vague image of what I wanted to do, but in reality, Wake was a small town and I was an outsider who had moved there with almost no connections. By chance, however, at a party to foster exchange between fellow outsiders who had moved to the town, I happened to meet a designer named Yuichiro Okano who had moved there from Tokyo as well. He told me that I should apply for a grant from the Fukutake Education and Culture Foundation, and he and his wife Makiko helped me make the application. And since I needed a theater company name for the application, it was the two of them that suggested I use the OiBokkeShi. That was adopted and I got the encouragement I needed.The grant application was accepted but I needed actors and staff to make a valid theater company. When I asked the local carpenter who had fixed some things in our house where I could find people to help me out, he said it sounded interesting and introduced me to some people in the local Wake chamber of commerce. That carpenter is now the stage director of OiBokkeShi, Hiroaki Ichikawa-san.But at that time we still hadn’t done any actual theater. And since desktop thinking alone wouldn’t lead to anything, I asked Ichikawa-san to gather some people and we held our first workshop demonstrations at night at the local community center. After two months of trial and error we managed to put together our first “Aging and Theater Workshop,” and one of the participants was Tadao Okada, the “Oka-jii” who is now our leading actor.

- It appears that that encounter with “Oka-jii” (Tadao Okada) has been important in your theater activities now.

- Yes, it has been. Oka-jii had long been caring for his wife who suffered from dementia, and he came to my workshop because he thought that experience of caregiving might be useful for us. He had worked in a long career as a hotel employee, and after he reached retirement age and had to leave his job, he started pursuing his long-time dream of being a movie actor, and he went to numerous auditions. Some of them resulted in his getting minor roles, such as a role as an extra in director Shohei Imamura’s Kanzo-sensei (literally “Dr. Liver,” English title: Dr. Akagi, 1998) and Kuroi Ame (Black Rain). Thinking that there couldn’t be anyone better for our Aging and Theater program, I telephoned him immediately after the workshop ended. And when I did, he immediately asked, “Does this mean I passed the audition?” And I answered laughing, “No, it doesn’t.” But I realized that in reality that’s what it amounted to. Ever since then, I have been making theater together with Okada-san.

At first, all I had was the idea that I wanted to make theater on this theme, but I hadn’t thought at all about what kind of plays to write. I visited Okada-san’s house numerous times and listened to his stories about everything from the War (World War II in the Pacific) to his experience in caregiving. He told me about the problem he had with his senile wife wandering aimlessly around the town, and how one night before dawn he found her gone and went searching all over town with the newspaper delivery man. Hearing this story, I decided to write a play about [senile] wandering. After that I set to work on the play “ Yomichi ni Hi wa Kurenai ” (The day never ends on a nighttime road).The title of the play came from something Okada-san always says. When I would go to his house to talk with him and the sun would go down and the roads would be dark as I got ready to return home, he would always say, “ Yomichi ni hi wa kurenai-yo ” (You know the day never ends (sun never sets) on a nighttime road). The sun had already gone down and ‘the day had ended.’ So the meaning of his saying was that since the day has already ended there is no need to hurry home. There is no need to hurry, so why not stay longer? When I heard his words, I felt that they had an especially important meaning in today’s world.This play is “walking theater” play that takes place while walking on the street of shops in the town of Wake. A young man who returns to the town for the first time in 20 years notices an old man from the neighborhood who used to always treat him like a son when he was little. So, he greets the old man and is told that his wife, who suffers from dementia has disappeared and he is searching the town for her. So the two start walking around the town looking for her together. I had the actual shop owners there play themselves at their own shops, and although they are amateurs as actors, they are pros at being themselves, so they all played their roles with bold confidence and vigor. The audience all follow along behind the young man, and in the process they lose the sense of what is reality and what is fiction. At first the audience starts out with the feeling that they are caregivers looking for a person with dementia, but as the story progresses they find out that the old man’s senile wife actually died years ago. They then realize that the old man himself is now suffering from dementia and is continuously searching for his wife, with this realization, they now become aware of the feelings of someone with dementia. With this play, I felt that the audience could experience the feelings of both the caregiver and the person with dementia. And since it was performed in the town, the townspeople could enjoy participating while also being given an opportunity to think about dementia, I feel.

“Aging and Theater Workshops”

- What do you actually do in your workshops?

-

In order to give a skillful acting performance in theater, you have to think about you have to become aware of how you normally talk and how you move your body. I believe that a workshop should be a tool to help people be aware of that kind of communication. So, in our “Aging and Theater Workshops” where the theme is how to interact with people suffering from dementia, I make the workshops a program where people become conscious of how they interact with the senile. The initial icebreaker I have the participants do some of the “ Asobi-litation ” (recreation ( asobi in Japanese) that can have a rehabilitative effect). One of these is a kind of recreation called “The Shogun Game.” In it, we give the numbers 1, 2 and 3 to different parts of the body, and when the leader, the Shogun, calls out a number, you quickly point to that part of your body. First, we have them point to the parts of their own body, but then, next we have them point to the same part on another person’s body, and when it changes like that they start to make mistakes in their pointing rather frequently. The game is fun because you make mistakes, and when someone makes a mistake everyone laughs or calls out, so everyone begins to get involved in the fun. In other words, not being able to do something properly can then become fun and something positive instead of negative. In the society we live in, when someone can’t do something properly they have to feel bad about it and feel that they must make the effort to learn to do it right. But in recreation we are freed from that pressure, and because of our human nature we can laugh at ourselves and enjoy mistakes.The elderly with dementia or with disabilities are people who gradually become incapable of doing a lot of things. But I believe that the way a person ages will be very different depending on whether they despise their own growing disabilities or whether they laugh and accept them as inevitable results of being human. Of course, I also believe that the atmosphere of the caregiving workplace can depend greatly on the values and approach that the caregivers bring to their interaction with the elderly. So, this icebreaker that I use in my workshops is intended to give the participants an experience of not worrying what a person can and can’t do and to focus on enjoying the moment fully in the spirit of recreation.After that, we next do a theater game using physical movement to communicate with others. Often when we are doing when we are doing ‘ Asobilitation ’ games, the families of the elderly will say they don’t want us to treat their grandfathers like a child, but even with simple games, changing the rules will increase the difficulty and the elderly will really begin to enjoy being involved in the lively interaction. Even some of them who say they won’t do such a game, eventually get into it and become absorbed in the game and enjoy it. In short, physical recreation isn’t a privilege of children only, it is something that adults can enjoy too. The essence of theater is using the body with enjoyment to communicate with others, so that is what I want our workshop participants to experience.Finally, I get them to think about “Senility and Acting.” Most of the participants are people with no experience in theater-making, but everyone has experience of acting in daily life. That form of acting that everyone experiences is, in short, ‘telling lies.’ For example, you may come home after buying something expensive and you are criticized for it, so you tell a little lie: “I bought it because it was on sale, so it was not expensive at all. This is a form of acting. Also, police have to act like police and parents like parents, etc., and these are cases where our social status can require an ability to ‘act’ appropriately. So, in our daily lives we are in fact playing several roles.Now, how does this reflect in the caregiving workplace? In the hallways of a home for the elderly, you may pass an elderly woman with dementia and she will say something to you like, “Oh, the glasses shop man.” Normally, you would reply, “No, I’m not the glasses shop man, I’m staff member of this home.” But, I think it can also be important at a moment like this for you to become an actor instead of a caregiver, so you can avoid negating the old woman’s statement and play the role: “Yes, it’s me, the glasses shop man.” So, I have the workshop participants break up into pairs, with one playing the caregiver and the other playing the elderly person, and then have them act out a scene in which the caregiver doesn’t negate a statement that comes out of context but instead accepts it and plays (acts) along to see how well they can carry on a conversation from there.

- I watched one of your workshops and I saw that it takes quite a bit of imagination to carry on a conversation after accepting (instead of negating) the disoriented (out of context) statement by the elderly person, and it made me wonder if it is really OK to accept it.

- In fact, when I was in high school, my grandmother was living with us, and that was a problem I actually had to deal with. My grandfather had died and she had lived alone for about seven or eight years, but when she got too old to live alone she came to live with us. One day, there was a croquette on the table and when I ate it, my grandmother said, “Oh, too bad, I was going to give it to the person living in the chest of drawers.” It was a moment caused by dementia. At that moment, I struggled with the question of whether I should correct her and say, “No one could be living in the chest of drawers,” or to go along with her and say, “Oh, I’m sorry, I ate it. Let’s give something else to the person in the chest of drawers.” I wondered whether I should correct her in hopes that she would return to her normal sound self, and if I accepted what she had said then might encourage her to keep going off into that disoriented world. In the end I decided to correct her, and I didn’t know if I had done the right thing.

When I began working as a professional caregiver and was constantly involved with many elderly people, I found that it seemed better to accept their dementia. I felt that if you keep correcting their dementia-based mistakes and conduct, it will never be a happy situation for either the caregiver or the senile. If you try to win the argument, neither of you will feel good about the exchange, but if you accept the statement that there is someone living in the chest of drawers it may develop into a scene where you have to go together to look in the chest of drawers. If we wanted to have my grandmother keep her happy attitude, perhaps the people around her had to think some more about the kind of environment they created for her. Thinking back now, I feel that we should have done a bit more to change the environment for her.- So, being able to play a role at times like an actor could have changed the environment in a way that made it easier for her to live in comfort, is it?

- Perhaps it would have. When you study about dementia, you learn that there are a set of unavoidable central symptoms in Alzheimer type dementia (memory disturbance, orientation disturbance, disturbance in reasoning capacity) that make the gradual increase in the number of strange statements or actions and small mistakes unavoidable. And if you keep trying to correct these each time, you are going to hurt the feelings of the person with dementia. Because even if they don’t respond to theory or reason, their feelings are still in tact and vulnerable.

This is why it is often said that when dealing with elderly people suffering from dementia it is unproductive to resort to theory or reason in the things you say to them but rather to try to communicate on an emotional level with positive feelings. This means that we have to accept things that are considered wrong in terms of normal common sense, and at times we have to pretend to see things that aren’t there. In other words we should respect the world that they see. And to do that, I realized, we have to be able to act [in the way an actor does].- After encountering the theme of “Aging and Dementia” and your worldview changed with the experience of working at a home for the elderly, what kind of theater do you want to make now with the elderly?

- The strongest feeling I had after encountering this theme of Aging and Dementia was the change in my view of uphill climbs and downhill descents. I feel that until now, through school and then as working people in society, there has been a demand for us to keep growing. We are all living amid the pressure to grow and improve what we do to today compared to yesterday and the seek higher achievement tomorrow than what we did today. But when you are at a home for the elderly, you are freed of that value system. The elderly continue the descent of the aging process, and that becomes the norm. It was a refreshingly new system of values for me. When I began working at a home for the elderly where there was no pressure to keep growing and improving, I felt something very comfortable about it.

The caregivers are bustling about doing their jobs, but the elderly are at ease and relaxed living the ‘slow life.’ They wake up in the morning and eat their meals and take their baths and then go to sleep at night, and that is repeated day after day. At first I wonder if it was alright for things to simply go on like that day after day, but soon I realized that there were good aspects to it as well. You can find joy in these simple aspects of daily life like eating meals and taking baths and enjoy living for the moment. When I was involved in theater-making in Tokyo, I didn’t even want to spend time cooking meals, so I just ate whatever was at hand, so I had no sense of enjoying aspects of daily life. But at the home for the elderly, there are people there who can’t even have meals without someone there to help them. In that situation, the important thing becomes how to make the mealtime experience as enjoyable as possible for them, and for me this brought a big realization about the importance of these basic acts of daily life and doing them properly. And it is these joys of daily life that I want to express in theater now.Oriza [Hirata] san taught me that you can bring more out of individuals by improving the environment they are surrounded with and acting in, and another valuable lesson I learn was the importance of valuing the individual’s personal history. If there is a person who has always spoken in a quiet voice, there is no need at all to use theater workshops to get them to speak in a loud voice. If they have always lived using a small voice until now, we can think of a dramatic context that skillfully makes use of that small voice. This valuing of the individual’s personal history is an important part of my Aging and Theater program for me. So, next I want to make a play based on the life experiences of my friend Oka-jii (laughs).(*) Haruki Miyoshi

Born 1950. President of the Life and Rehabilitation Research Institute. An expert in the field of caregiving and rehabilitation. An advocate of placing importance on basic human values in the work of caregiving, Miyoshi gives “Life and Rehabilitation” lectures around the country to communicate the importance of bringing imagination to the work of caregiving for the elderly. He has pioneered a new wave of welfare caregiving by starting such programs as The Society for the Study of Removing [elderly] Diapers and The Society for the Study of Removing [intravenous, urinal] Tubes. Author of numerous book such as Kaigo no Susume! – Kibo to Sozo no Rojin Care no Nyumon (2016).

Cameraman no Hentai

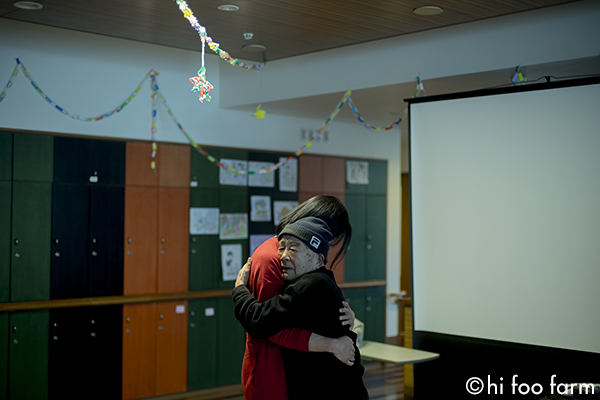

(performance at Mimasaka Town, Okayama pref)

(Jan. 2018 at special-needs nursing home Keiryuso)

Photo: hi foo farm

“Wandering Senility Theater”

Yomichi ni Hi wa Kurenai

(Jan. – Mar. 2015 at Wake town eki-mae shōtengai)

Related Tags