- I would like to begin by asking about your personal history. What year were you born?

- I was born in Chofu, Tokyo in 1965.

- Since Yukio Ninagawa was born in 1935, you are closer in age to being a son to the director. I am told that you were originally an actor. How did you first meet Ninagawa, and how did you get into set design as a career?

- From elementary school age I was a member of a children’s theater company, in an audition for the role of Medea’s son for the first production of Ninagawa’s Medea . I got the role and that was my first real stage performance. I was a sixth graders in elementary school at the time, twelve years old. Ninagawa-san was 42 or 43 at the time and the way he worked on plays was different from today; if things weren’t going as he wanted, he would get mad and send ashtrays flying! (Laughs)

- That was in 1978, wasn’t it. Looking at reference materials from the time, we see that you also acted in other Ninagawa productions including Chikamatsu Shinju Monogatari (1979), Romeo and Juliet (1979), NINAGAWA Macbeth (1980), Genroku Minato Uta (1980), Nanboku Koi Monogatari (1982), Medea in Athens (1983) and France (1984), NINAGAWA Macbeth in Amsterdam and Edinburgh (1985) and in New York and Vancouver (1986) and Tempest (1986).

- Yes, that’s right. After performing in Medea , it was like the assistant director would say to me that they were doing such-and-such a play next and did I want to play a role in that too. In that way, they kept inviting me to perform again and again. During my junior and high school years I thought that I wanted to be a professional actor in the future, but when I saw stage art like the set for Chikamatsu Shinju Monogatari with its dynamically moving buildings (stage art by Setsu Asakura) and NINAGAWA Macbeth , where the entire stage was turned into a (home) Buddhist altar (stage art by Kappa Senoo), I thought they were amazing. Even though I was still a child, I became interested in such theatrical spaces. To begin with, I had always enjoyed drawing pictures and building things, and that may have been part of it, so when the time came I decided to go to Osaka University of Arts. But, at the time I was still performing as a stage actor, so I was debating in my mind whether I should continue to become a professional actor or become a stage technician/artist.

- Did you consult with Ninagawa about studying stage art at the art university?

- It wasn’t really a matter of consultation, but just that I told him I was applying to go to Osaka University of the Arts and he asked, “What are you going to study?” When I said I was interested in stage art, he just said, “Is that so.” (Laughs). In my sophomore year at the university I represented my school in the “Japan-China Stage Art Student Exhibition” (1985) with a model of a set I had designed for the play Caligula , and when the exhibition was held in Shinjuku, Tokyo, I asked Ninagawa-san to come to see it. The set plan I had designed was all black with a mirror in the center with steps on both sides and golden ropes strung from the ceiling like a spider’s web. Later in my senior year at the university, Ninagawa said to me one day that NINAGAWA STUDIO was going to put on a new play soon and did I want to try doing the stage art. That play was Niji no Bacteria (Bacteria of the Rainbow) (1987) written by Isamu Uno, a writer of my same generation.

- So, your debut as a set designer came when you were still a university student. That is surprising to hear. Then who was your mentor, or teacher as a stage designer?

- At the university, I had classes with teachers who worked in the Takarazuka Review and on TV set art, but there was no teacher of stage art. So, I guess if I had to cite one teacher, it would be Ninagawa-san. I learned on site about stage work from many staff of each production. At the time, at Osaka University of the Arts there was Hironori Naito of Minamikawachi Banzai-1-za and Hidenori Inoue of Gekidan Shinkansen, but I didn’t think of entering either of them, so I never got any experience working in a student theater company. Another teacher there was Satoshi Akihama, but he just said to me, “So, you’re at Ninagawa’s company,” and that was it. Even though I wasn’t officially part of the company at that time. (Laughs)

- For Niji no Bacteria (Bacteria of the Rainbow) that play involves interactions between the characters at the shared sink of a small old apartment building. In the stage space of Benisan Pit, there was a realistic apartment room covering the entire space in a design by which the audience looked on at the happenings between the actors at the shared hallway sink from inside that apartment room. The lighting design was by Tamotsu Harada, the sound creator was Masahiro Inoue and the stage director was Shinichi Akashi, all of whom are the stage staff that would continue to work with Ninagawa over the long years to come.

-

Since this play was a story that took place in an apartment building, Ninagawa asked me if there was a way to make a stage plan in the form of an apartment room. So, I thought about the possibility of not making the usual audience seating area but making an apartment room itself the audience seating area. At the time I didn’t really know how to draw proper layout plans, so after reading the play I just drew a 3D picture of the image I had for the set. I explained that here would be this room and there would be a place in the center where everyone would gather, and I got some of my student friends and the actors to help me build it directly into the theater space. When we did Gips (“cast” of the kind used for broken bones) by [Isamu] Uno-san in the same year, he said he wanted something with the feeling of concrete, or something like plaster walls. But, even with a clear image like that, I still didn’t know how to make it as a set. So I would go to learn from a wall plasterer or go to study from the stage art people at the Haiyu-za company as a trainee. Normally these are things that aren’t possible, but when I told them I was working for director Ninagawa-san, they were all happy to help me learn.

- When did you become an official member of NINAGAWA STUDIO?

- When we were working on Gips I found that all of a sudden I was being treated as a member. I was still a student at Osaka University of the Arts at the time but I was in Tokyo most of the time, so I wasn’t going to classes, and in the end it was decided that I would have to do a year of school over again, but in December of my senior year I finally quit and returned to Tokyo.

- NINAGAWA STUDIO was a place where the young staff and actors did a lot of experimental works with Ninagawa. From the company’s first official production Three Sisters – Keikoba to iu na no gekijyou de jyouen sareru (1984; Chekov’s Three Sisters “performed in the stage known as the rehearsal studio”) when it was called GEKI-SHA NINAGAWA STUDIO, and the company’s second production done under the name Young NINAGAWA Company, titled 1991 – Matsu (1991: Waiting) (by the Young NINAGAWA Company members with co-direction by Yukio Ninagawa, Naoya Takayama and Sonsyo Inoue), it was a group that did a number of theater works that left a deep impression.

- Matsu (Waiting) had a number of versions like 1992 – Matsu and 1993 – Matsu . The actors would choose works that they like and do etudes from them in an audition type atmosphere, from which interesting things would be picked up and worked into a composition, but we usually wouldn’t know what it was going to be like until just before the first performance was scheduled to take place. Things like putting the actors in an acrylic box or spraying out sparks from a grinder, these were all things done on an experimental basis by everyone at NINAGAWA STUDIO. In the small spaces where we worked, raw materials are effective, so we would do things like spreading real soil on the stage and pack it down. We did things like taking the audience space in a theater, reducing in half and using the entire space as the stage.

- The year after your debut as a set designer, in 1988, for your third production you were put in charge of stage art for the performance of Hamlet at the Spiral Hall theater in Tokyo. This production Followed Ninagawa’s concept of taking the Hamlet story and turning it into a single night’s fantasy taking place on the night of the Japanese Dolls (Girls’) Festival ( Hina Matsuri ), and the entire stage was turned into the equivalent of the stepped platform ( hina dan ) that the Girls’ Festival dolls are traditionally displayed on during the festival. The story begins with a setting in Japan’s Warring States Period (16th century), and as the play proceeds the time frame moves up gradually to the present, while the hina dan is converted into a stepped stage. It was a fascinating conception and device accompanied by constant changes in the characters’ costumes as well.

- [For the full-scaled Spiral Hall theater space] that was the first time I actually made a proper miniature set model. I wasn’t used to making models like that and I remember working all night for many days to finish it. I didn’t have any textbook to work from, so I kept asking a number of people about the things I didn’t know until I learned how to do things like the set design drawings (blueprints). On site everyone treated me as a child anyway (laughs). In fact, when the company was doing the production of Hinmin Club (Poor people’s club; 1986, stage art by Setsu Asakura), Ninagawa-san had sent the script and the theater’s blueprints to me at my school dormitory in Osaka and asked me to draw some plans for the stage art. I believe he was testing me then. Then the next year, with the production of The Tempest , they let me work as an assistant to the directing department staff and I was able to learn a lot about the professional worksite. The stage director that time was Akashi-san and it involved changes of sets during the performance.

- After meeting Ninagawa for the first time at the age of 12, you were able to gain a lot of unique experiences in the Ninagawa theater world on your way to becoming a stage art designer. Would you tell us how you feel about that influence?

- Even as a child, I felt from the beginning that Ninagawa’s directing stage art was amazing. But, since that is what I grew up with, I didn’t feel that it was something unusual. That’s why I was able to do designs like the one for Caligula that I did as a university student, I believe.

- Do you feel that having been an actor originally helped you as a set designer?

- I know that stage art isn’t a showroom but something that only becomes complete when the actors are actually moving around in it. I have a sense of that need for them to be easy to move around in and easy to use. When Ninagawa-san directed a production of Hideki Noda’s play Byakuya no Valkyrie (Valkyrie of the midnight sun), it was decided to construct a giant Mt. Fuji on the stage, which required that the slope become quite steep. The actors said that they felt scared climbing up and down it as they acted. Usually it is the job of the stage director to settle issues like that between the actors and the set designer, but since I am able to see things from the actors’ standpoint, I sometimes am able to talk to them directly and make the necessary adjustments in the design.

- Looking at the reference materials that remain, I find that when you add to the theater productions all of the other things like concerts and small-scale works you have done stage art for Ninagawa, the total comes to some 110 stages. It seems as if yours is an inseparable working relationship.

- In the past, the pace was either two or three productions a year, but after the age of 70 the number of productions Ninagawa-san does a year has increased, so not it is definitely as if I am his resident stage designer. He tells me that I can do work for other directors if I want, but it is just physically difficult due to the schedules (laughs).

- In the 1980s it was Setsu Asakura who did the stage art for the commercial productions, and in the 1990s it was Toshiaki Suzuki who did the stage art for productions like The Tempest and The Flying Dutchman , but from the latter half of the 90s it was you who did most of the stage art, wasn’t it?

- Yes, it was. I think it was easy to communicate things verbally. It was enough for Ninagawa-san just to say “I want that kind of feeling from such-and-such a production that time” and I could get a feeling for what he wanted. Still, when I was young, although it never reached the level of an actual fight between us, there were times when I struggled with things. In the old days, Ninagawa-san used to bring books and other materials to my house and talk over things in detail together with my plans, but there were times when I didn’t want to meet with him, so I pretended to be out. That is a famous story (laughs).

- The fact that Ninagawa originally wanted to be a painter is a good indication of how strong his obsession with visual presentation as a director. And he often changes the stage art during the course of rehearsals. Doesn’t that make things difficult?

- I once asked him why he didn’t the stage art himself. He said that both directing and stage art have their respective specialized skills and he doesn’t know those of the stage art side, and even if he tried to do it the results wouldn’t be interesting. He told me that the process he found interesting was for him to give me a visual concept and have me come back with a plan and then start multiplying the images again from that point.

- How does he give you the visual concept?

- Sometimes it has been in the form of drawings or sketches he has done, but now it is mostly verbally communicated in the form of non-specific references based on mutual understanding. I listen to that and then do a specific plan for him to look at. From there, it becomes a process of my rethinking the plan if it seems different from what he had in mind. There are also times when I will build an initial set into the rehearsal studio and then, during the course of rehearsals we will want to change it. Lately, Ninagawa-san’s directing is done largely like a jazz session and the play takes shape during the studio work, so the stage art plans are also created increasingly on site in the studio. Ninagawa-san often says, “My staff can do anything,” but it is not a matter of us being able to do everything (laughs). It is actually a process of our theater staff putting our heads together and deciding what things will be necessary and then preparing everything while discussing things among ourselves.

- What is the process like when you are creating the stage art on-site as you have just mentioned?

- For example, in the case of our production of Never let Me Go (stage script by Yutaka Kuramochi based on the novel of the same name by Kazuo Ishiguro), we had the basic set to begin from, which was a school classroom setting, and for the other scenes we would make modifications to it as the rehearsals proceeded, saying things like, “Let’s add some props of the school in the closed audiovisual room,” or, “For the open space, let’s spread the entire stage with a marsh pond.” That is the way the plan took shape on-site.

- Is the fact that there are a lot of movable (wagon or caster-mounted) sets lately due partly to this change in directing method?

- Well, long ago when we did plays like Chikamatsu Shinju Monogatari , we would construct a lot of set components to group together in different combinations for the different scenes, but now we change the whole set by scene, and I feel that is why there are more moving (wagon-mounted) set components. For example, with the production Musashi (written by Hisashi Inoue ), the temple set and the bamboo grove and others were all built as separate pieces that were movable. When we started rehearsing we had only received the opening part of the stage script and the only notations in the script were that there would be a temple and a bamboo grove and that the temple building would have a walkway leading to it like a Noh stage. So, we were forced to improvise, and we decided to make each part separate so they could be brought together in a variety of patterns as needed to be. Also, I believe that since our base has become the Saitama Arts Theater with its deep backstage area, we have begun making more stage art designed with a vertical space that enables it to be wheeled out from behind the stage like zooming in and out.

- In the end, the Musashi production truly had marvelous stage art.

- While Mr. [Hisashi] Inoue was writing the script, we all went to his house. When we asked him about the stage art, he delightedly said, “This is it,” and he pointed to his long outside hallway with glass sliding doors looking out on the bamboo grove in his garden, and we could see the bamboo sway as the wind blew through the garden. I used things like that as hints for the stage art plans.

- At the Saitama Arts Theater, Ninagawa has been directing a Shakespeare series since 1998 that will eventually present all 37 of Shakespeare’s plays. The first production was of Romeo and Juliet and the production of Richard II scheduled for January of next year (2015) will be the 30th in this series. The second of the series was Twelfth Night and the eighth in the series was Macbeth , and it was from that production that you have been in charge of the stage art. Among this series, the pure white stage art of Titus Andronicus (2004) left an especially strong impression on me. The costumes were also white and red thread was used to create countless traces of blood.

- It was not specifically because it was Shakespeare that we arrived at that policy, but we often use decorative backdrops. In the case of Titus , we had the opportunity to go to Europe at the time and, thinking that I might find something to serve as reference, I made a visit by myself to Rome. The symbol of Rome is the wolf, and I saw a lot of small wolf figures with a handmade look being sold as souvenirs. So, I bought a white wolf figure to take back to Ninagawa-san. When he saw it he said, “Are we going to have a white set?” (Laughs) Perhaps I had wanted to make it white from the beginning, and I ended up making a giant reproduction of the white wolf figure to use as part of the stage art.

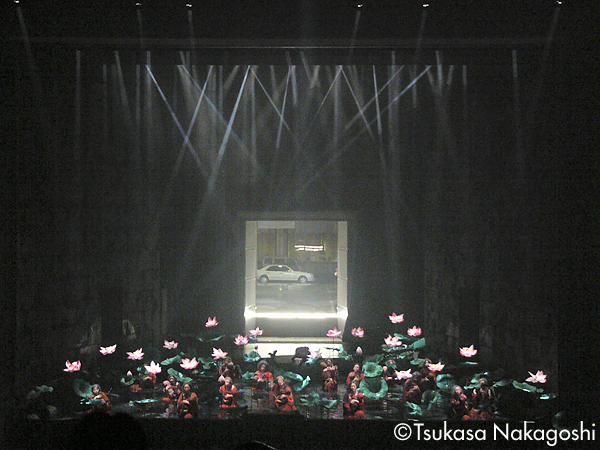

- There are often large devices used in Ninagawa’s stages. For example, in the production of Medea (2005) starring Shinobu Otake at Theatre Cocoon (Tokyo), the entire stage was covered with a pool of water filled with many large lotus flowers. I have never seen such a water-soaked production of Medea . Where did that idea come from?

- I had a dream in which I saw Otake-san walking with her feet splashing up water as she walked. When I told Ninagawa-san about that dream, he said at first that it would probably be difficult to do, but several days later he suggested, “What about a set like a lotus pond?” He has always loved lotus flowers, and I used them once in the stage art for The Greeks (2000).

Covering the entire stage floor with water was the first for Ninagawa-san too, so we made a pool in the rehearsal studio to rehearse in the same water conditions that would be used in the performances. In order to determine what water temperature would be OK, I had discussed with the stage director how effective the sound of splashing water would be, and how much the actors would be able to move around, we prepared the studio to test these things in conditions that were as real as possible and then made the necessary changes. We tried various types of costumes and makeup to judge what was best and the various planners stuck with the job to make the necessary adjustments. This is something that would not normally be done, I believe.- The Greeks (by British director John Barton and English-language translator/playwright Kenneth Cavander) is a trilogy adapted from ten ancient Greek tragedies that takes about nine hours to perform in its entirety, and this production is one of Ninagawa’s representative works. The stage is designed with audience seated facing each other on either side of the stage and throughout the performances a giant pendulum continues to swing back and forth as a symbol of time.

- The opposed audience seating arrangement and the pendulum were Ninagawa’s ideas. He kept insisting that there be a gigantic pendulum to symbolize time, so I was wondering what to do (laughs). I had to think about how to hang it from the theater ceiling, and consult with a set-making company about how to make it motor-driven. I learned a lot by working on big set devices like that. Since myself and our staff have continued to accumulate such experiences, we are able to respond to Ninagawa-san’s demands, but still, it is difficult each time.

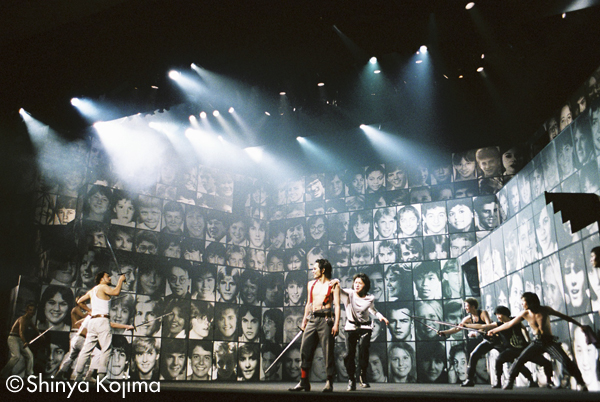

- In the production of Romeo and Juliet (2004) starring Tatsuya Fujiwara and An Suzuki, the set had steeply rising walls covered with what looked like funeral photographs of many young people from various countries around the world. The result was an emotionally moving image of the young people who go to their deaths in ethnic conflicts.

- Ninagawa-san had an image of lines of funeral photographs of a fictional Romeo and Juliet and fictional young people. We had a hard time finding appropriate photo portraits, but I found a high school graduation album of my older brother’s when he was studying in the United States, and it contained the portraits of many foreign students from various countries. I ended up selecting the portraits from that album including my brother’s.

- There was also a large-scale device used in this year’s production that drew so much attention, Tomin Suru Kuma to Soine Shitegoran (Try lying down to sleep with a hibernating bear) (2014), written for Ninagawa by the emerging novelist Hideo Furukawa. It is an extraordinary play about the sacred struggle of a legendary bear hunter and a dog, and it was staged with a device by which a giant Buddha sculpture was rotated to become an image of a dog, and a quick-change device is used to change an isle in the audience seating area into a rotating sushi counter.

- That was a play that had a lot of stage instructions in the script and it became a process of thinking of ways to realize them. The sushi counter was Ninagawa-san’s idea (laughs). Creating that kind of [sushi counter] picture in the isles of the audience is not something that most designers would try to do, I believe, but I feel we were able to do it because of the good working communication that exists between our stage staff.

- There was also a very bold set used in Taiyo 2068 (2014), a play rewritten from the old work for Ninagawa by the young playwright Tomohiro Maekawa . The setting is a world in the near future that has been destroyed by biological terrorism and the story revolves around conflict between the surviving former humans and a new race with miraculous powers resulting from the virus used in the terrorism. In the staging, the set is divided into upper and lower portions, with the upper portion being the daytime world inhabited by the former humans and the lower portion being the night world inhabited by the new race that can’t live in the sunlight.

- With that work, the stage art was decided in a unique way. The set for the daytime world was an abandoned Japanese house designed by Setsu Asakura, who passed away this March, and the set for the underground night world was one that I designed when we did Hamlet . The floor surface was all made of acrylic boards so that you could see what was going on below. It appears that Ninagawa-san arrived at the concept of a world with day and night and a space with old and new that combined the set designs of the great master [Asakura] and my own into one.

- Ninagawa works with a wide range of plays, from Shakespeare to those of young contemporary playwrights. Among stage artists there are those who have their own personal style, but in your case you create very different worlds depending on the play. How do you go about confronting a play and drawing up a stage art plan for it?

- This is a habit I have had since I was in the company’s directing department, but the first thing I do is read the script and draw red lines under all the stage directions in it. I feel uneasy if I don’t do this. From the stage directions I get a general idea of the situations involved, and then I read the play all over again from the beginning. Then I begin collecting reference materials concerning the play and its story. I don’t think about how I am going to use it initially, I just gather as much material as I can and I take it to my first discussions with Ninagawa-san. Then I begin writing out everything about the play and the staging; everything I can think of about the stage directions, about the set and props based on the historical backgrounds and places, about the movement of the actors and the movement of the things on stage, what will be broken, in other words everything I can search for. Ninagawa-san and I both like paintings, artists like Anselm Kiefer and Andrew Wyeth, so I make a lot of use of painterly images.

- Listening to what you say, it sounds as if all of this stage art is the product of a collaborative creative process between you and Ninagawa, isn’t it?

- Yes, I believe it is. When I work with other directors, I am the type that will go to the rehearsal studio more than most, but when I work with Ninagawa I am at the studio all the time. I work by taking all the materials I have gathered and taking with the director and at the same time I talk with the stage director’s team that will actually be operating the set. And, I believe that the reason I have been able to work in this way for so long is that, in the end, the things Ninagawa-san and I like are very similar. And, above all, I really appreciate having met Ninagawa-san.

- Finally, I would like to ask if there are any plans for overseas performances on the horizon that will be using your stage art?

- The things that are scheduled at present are performances in Hong Kong and Paris of the Saitama Gold Theater production of Karasu-yo, Oretachi wa Tama wo Komeru (Ravens, We Shall Load Bullets), London performance of Hamlet , and London, New York and Australia performances of Umibe no Kafka (Kafka on the Shore).

Saitama Gold Theater 6th play

Ravens, We Shall Load Bullets

(May. 16 – 19, 2013 at Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater-Main Rehearsal Hall)

Photos: Maiko Miyagawa

Watashi wo Hanasanaide (Never let Me Go)

(Apr. 29 – May. 15, 2014 at Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater-Main Theater)

Photos: Takahiro Watanabe

Stage art of Musashi

(May. 4 – Apr. 19, 2009 at Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater-Main Theater)

Saino-kuni Shakespeare Series 13rd

Titus Andronicus

(Jan. 16 – Feb. 1,2004 at Sainokuni Saitama Arts Theater-Main Theater)

Photo: Chigusa Takashima

Photo: Masahiko Yakou

Medea

(May. 6 – 28, 2005 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Shokubutsu-Monogatari presents

Romeo and Juliet

(Dec. 4 – 28, 2004 at Nissay Theatre)

Photo: Shinnya Kojima

Bunkamura 25th anniversary play

Taiyo 2068

(Jul. 7 – Aug. 3, 2014 at Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon)

Photo: Shinji Hosono

Tsukasa Nakagoshi

Another key part of the Ninagawa world

The stage art of Tsukasa Nakagoshi

Tsukasa Nakagoshi

Born in 1965, Nakagoshi majored in stage art at Osaka University of the Arts. He made his debut as a stage art designer in 1987 with the NINAGAWA STUDIO production of Niji no Bacteria . Since then, he has designed the stage art for many plays directed by Yukio Ninagawa (see the accompanying table). Representative works in recent years include the stage art for Hisashi Inoue ’s Musashi (2009) , Haruki Murakami’s Umibe no Kafka (Kafka on the Shore) (2012), Shakespeare’s Henry IV (2013), Kunio Shimizu’s Karasu-yo, Oretachi wa Tama wo Komeru (Ravens, We Shall Load Bullets) (2013), Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2014), Tomohiro Maekawa ’s Taiyo 2068 (2014) and others. He has been a winner of the Best Stage Staff Award of the Yomiuri Theater Grand Prix in 1995, 2005 and 2006.

Interviewer: Akihiko Senda, theater critic

Related Tags