First encounters with theatre

- I have heard that your oldest experience of theatre was with the [all female] Takarazuka musical revue theatre.

-

My mother and my grandmother were both fans of the Takarazuka Revue and every month they took me to the big Takarazuka theatre to see the performances as a little child. After a while they got the misguided idea that they would get me to join the Takarazuka company, so from the age of nine they began sending me to Japanese traditional dance lessons and singing and regular dance lessons. I didn’t like such things and wasn’t good at them, so I really disappointed them (laughs). Our family had a very dominant father and it seems that being Takarazuka fans was their form of escape from that daily burden. But, I watched the whole situation with a rather cool detachment, wondering if they really got satisfaction from their Takarazuka diversion.

- What were your theatre encounters after that?

-

The first theatre ticket I ever bought with my own money was shortly after I entered Kyoto City University of Arts. I went to see a performance of Juro Kara’s Red Tent company at Shimogamo Shrine.

- That is a big leap from Takarazuka to the [underground] tent theatre of the time (laughs)!

- I myself don’t even know what made me decide to go see it. I had moved to my own apartment in Kyoto and was living alone and independent for the first time, and when I saw this poster for the Red Tent performance hanging on a bulletin board at the university, I just decided that I had to go see it. The play’s poster was designed by Tadanori Yokoo or Suehiro Maruo, I believe, and I already had a liking for that style of aesthetic work. While in high school I had read quite a bit of Shuji Terayama’s works as well.

- How was it when you actually went to see it?

-

I got lost on the way in Tadasu no Mori park and then, way back among the trees I saw the glow of a red light. I found the tent and went in timidly, not knowing what to expect, and there was movement and commotion and people everywhere and I didn’t know what was going on (laughs). But, I will never forget that experience. The play they were showing that time was Shojo Kamen , a story about young female fans of Takarazuka who go all the way to Manchuria to see the star Yachiyo Kasugano perform. From outside the tent the “young female fans” come in one after another, singing as they come. Under the padded air-raid hoods they have on you can see the distorted shapes of masks they wear. Finally they have the “tent collapse” scene in which the closed space of the tent comes down on everything. After seeing that I was hooked completely.

- After such a powerful first impression, didn’t you think about going into theatre? At the time, the company “dumb type” was beginning to be active at Kyoto City University of Arts, I believe.

- If I had been in Tokyo, perhaps I would have gone to meet Kara-san, but since I was in Kyoto, well …. I went to see the performances of dumb type, but rather than their kind of sophisticated approach, I was attracted to Kara-san’s excessive intensity.

From craft to photographic art – Activities as a contemporary artist

- At university you majored in craft, and you got into fiber art.

-

At first I was doing traditional crafts, making kimono fabric and folding screen designs using the

katazome

(stencil dyeing) and wax-resist dyeing techniques.

- While you were a student at the university you held a solo exhibition of fiber art. Looking back at that exhibition from today’s perspective, there appears to be a very theatrical or dramatic aspect to your work.

- Yes. It was my first solo exhibition and I hung red cloth all around the room. At that time I was creating works that were like enlargements of my body. I had also stayed in Tibet for a while to see the temples of Esoteric Buddhism. Looking back, it might have been my own kind of “Red Tent” (laughs). Kara-san’s influence might have been there without my realizing it.

- After graduating from university in 1993, you presented a work titled The White Casket that had live women dressed as “elevator girls” [uniformed department store elevator attendants] in the gallery as objects in an installation. What was the concept behind that work?

- After graduation I no longer had a studio to work in or seminars to attend, and I was thinking what to do next. I didn’t create any works for a while and worked as a part-time instructor. My commute took me past a department store where I saw the female employees in uniform gather at opening and closing times to all bow at once. Then suddenly I saw these women, who were continuously performing their role before the audience that is the society at large, in relation to myself, as I was now alone with no place in society. I became interested in women who had to act like robots reciting their given words and actions over and over in a ritual-like way, and I decided to do a work based on this image.

- In the [Japanese] art world at the time, this work of yours was written about in terms of concepts like feminism and gender, the nature of symbols and anonymity. I believe it was seen and critiqued as an installation work, rather than as a theatrical performance. Anyway, going from craft to performance-like work seems to be quite a sudden change for an artist. Was there some influence there from Shuji Terayama or others in this apparent leap?

- No. That wasn’t a factor. What may have appeared to others to be a sudden leap to a new realm was in fact an inevitable act of necessity for me.

- The following year, at the “Art Now ’94 – Revelation and Sustainability” group exhibition at the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Modern Art (present Hyogo Prefectural of Modern Art) you presented a work that had female guides dressed like “elevator girls” placed around the exhibition gallery.

- For that work I had the female guides actually speaking lines for the first time. There were difficult explanations written by a curator to be read as if a museum of modern art’s guides were guiding tourists through the exhibition. I took those explanations and rewrote them into gradually rougher and more superficial lines. It was absolutely in the realm of performance. But, at the time, it didn’t go that one step further into the realm of theatre.

- Why was that?

- When using live people, things naturally do not go exactly as you wish. There were a continuing number of cases of trouble that resulted. Probably a part of it was due to the fact that my artistic roots were in craft, but I got this frightfully disturbing feeling, “What is this irregular mass of forms?” That made me feel that I couldn’t go on using live human beings in my work and got me moving in the direction of photographing the women instead and creating composite photographs from the images. Photographs have a lot in common with crafts, and if you follow the steps properly you can be in complete control of the results.

- In 2000, you began work on your My Grandmothers series. In this series you had the young women who served as your models imagine themselves 50 years from now and then you worked with them to create a photograph in that image. For the works of this series, you talked with the women to help them develop their image and the story behind it in order to create a suitable setting for the background and costume for the photograph that would portray them 50 years later; and sometimes that even involved going to overseas locations. I believe that process is very close to that of theatre.

-

I think it is closer to creating a scene for a movie. We used special-effects makeup and computer graphics and thought together with the model to create a high level of authenticity that contained as many aspects of her story as possible in a single photograph. For this reason, I especially got the feeling that it was an initial approach to theatre that was very close to creating a work of craft.

- In that series, did you ever have the feeling that you would like trying to use that creative process to do a performance work rather than consolidating it in one photograph?

-

Well, I believe that theatre is an art of making works of such scenes, or “intervals,” but at the time I was not concerned with the creative process as much as I was interested in showing the result of the process. In fact, we do have some interesting video footage that was taken during the process of making the

My Grandmothers

works, but that footage is nothing more than a record [not taken with the idea of using it as material for a separate work].

- The work Windswept Women that you showed at the 2009 Venice Biennale consisted of giant portraits of women four meters tall, with wild images of women facing in defiance the winds that buffet them. As the subtitle The Old Girls’ Troupe indicated, the contents of the work seemed to be a premonition of your eventual shift to theatre.

-

Indeed, it did seem to forecast everything to come.

Theatre activities beginning from a modern art museum

- Now, at last, I would like to ask you about your theatre activities. In the Kyoto Arts Center’s regularly held “Meirin Chakai” meeting/event series, where an artist is selected each time to chose a subject and lead the event, you were the selected artist for the March 2010 meeting. For that meeting you chose the title Sakuramori Chakai (meaning, “tea ceremony for protecting the cherry trees) and it was staged in a very theatrical way.

- For that event, I actually wrote a script for the first time. Without letting the actual attending guests know, I planted five actors in the audience playing the parts of different types of Kyoto residents and had them act out a scenario in the form of a free-for-all internal battle. I had prepared a simulation-type script to cover the possible developments if the actual audience began participating in the battle. There were a number of members of the audience who didn’t realize right to the end that it was all a staged play and everyone really got into it and the developments.

- I was at the event that time, and I came away very much impressed by your talent as a scriptwriter. Then in November of that year, you did a work titled “Café Rottenmeier” at Festival/Tokyo in which you used real elderly women dressed up as maids in a café. In addition to operating the café, you also had short theatrical performances.

- It was fun, but it was quite difficult at the same time. The elderly are inherently free, so you can’t control what they do. But that experience gave me the dream of someday doing a seniors theatre project.

- After the lead-up of the Meirin Chakai performance and the Café Rottenmeier piece, you began your full-fledged theatre efforts in July of 2011 with the start of your 1924 Trilogy . The first work of your 1924 trilogy titled Tokyo-Berlin premiered at the Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art. For that work you took as your subject the Tsukiji Shogekijo (Tsukiji Small Theatre: opened in 1924 as the first theatre dedicated to the performance of Japan’s modern “ ShinGeki ” (New Theatre movement) performances).

-

For a long time I had been thinking that I wanted to do theatre someday. At the same time I had always felt somewhat uneasy about being in the contemporary art world. Contemporary art doesn’t become a truly physical art form with regard to using the live human body. I like the “white cube” (the [art] gallery with its white walls), but it can’t become one with the body. There is something in me that gets excited by the dark atmosphere of the theatre, and that had led me to the point where I could no longer be satisfied working in the white cube. But, even if I wanted to do theatre, I had no career credentials in it or any connections with any theatres. When I asked Shinji Komoto of the curatorial department of the Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art for advice, he asked me if I wanted to try doing something first at the museum. He showed me the museum’s exhibition schedule of events for the year and it happened that there were a good number of events related to the 1920s, like a Yumeji Takehisa exhibition and a Moholy-Nagy exhibition. So, I decided to use the exhibition galleries of the Mohoy-Nagi exhibition to do a work on a subject from the 1920s. When I started doing research, I found that 1924 was the year of the opening of one of the most important theatres in the history of Japanese theatre, the Tsukiji Shogekijo. The year before, Japan had suffered the disastrous Great Kanto Earthquake, and international events included the death of Lenin and the Surrealist Manifesto was issued in France. It was a period that saw a rise in numerous “isms. ” For Japan, it was a pivotal year in which the country set out on a new course.

- I’m surprised that your theme of the 1920s came from such a chance discovery. You did detailed research on the Tsukiji Shogekijo theatre and its founder, Yoshi Hijikata and the artist Tomoyoshi Murayama and others and wrote a play involving this actual place and the people related to it. Why was that?

- I just had this feeling that if I was going to do theatre, there was no way to get around dealing with the Tsukiji Shogekijo. It was a natural conclusion for me. If the things that we are doing in art today are in some way an extension of the history going back to the time in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) when Tenshin Okakura and Ernest Fenollosa created the word for fine art ( bijutsu ) that didn’t exist in Japanese before that time, in the same way, the roots of today’s [Japanese] theatre can be traced back to the Tsukiji Shogekijo that Kaoru Osanai and Yoshi Hijikata created. So, I thought it was natural to begin by thinking about that place and time.

From the Meiji Period, the government gave support for the development of the fine arts and music, etc., but theatre developed only on the blood and tears and hard work of the people, of private citizens. What’s more, theatre performances couldn’t be reproduced, so you had cases of Japanese going to Moscow Arts Theatre to see a play, listen to it and then go back to Japan to put on a performance of it, with all the shortcomings and misunderstandings such a process would involve, like a relay-the-message “telephone game.” That was the kind of thing that was happening over and over at the time. I thought that these are the kind of little-known facts that people should know about. That is why I definitely wanted to do a production of the play Kaisen (Sea Battle) that was the first piece performed when the Tsukiji Shogekijo opened. And, I believe I was able to choose that subject because I was an outsider in the theatre world who didn’t know any reason not to. The development of theatre [in Japan] has been a process of negating the previous generation’s work that can be likened to “patricide.” I never imagined that dealing with the subject of the Tsukiji Shogekijo was virtually taboo in today’s theatre world.- Was there objection to having an outsider deal with the subject of Tsukiji Shogekijo?

- I was told that for theatre people it was unthinkable to deal with that aspect of theatre history. Also, one of the geniuses among Japanese theatre directors, Yukio Ninagawa , came to see Kaisen , and after the performance he came to me and said it had been very interesting and that it was something he couldn’t have undertaken. He went on to say that he had perhaps had some misunderstanding about the kind of person Hijikata had been and that the play made him more interested in the history of the period. Hearing that, increased my own interest in the history of theatre as well.

- What were your thoughts about the difference in the approach to history between theatre and art?

- You could say that the approaches are the complete opposite of each other. Because basically, people in contemporary art don’t negate Marcel Duchamp. Contemporary art takes everything in and becomes hypertrophic as a result. The artists probably feel it is un-cool to say things like, “Bring down the previous generation.” Especially the young generation appears to be detached from history, and it seems that the only thing they need is concepts formulated by the individual. I find that freedom in the fine arts to be quite frightening. In contrast, theatre continues to maintain what might be considered a form of traditional stance of “destroy [the work/concepts of] our fathers’ generation (the previous generation). And, that may be one of the reasons that I feel an affinity for theatre.

- Although it may be true that the theatre world’s tradition of actively negating the work of each previous generation has led to the continuing birth of new forms of expression, but I think that this tradition that can be likened to “patricide” has also led to the loss of many things of value. You may be one of the only artists today who is looking for material for plays in parts of Japan’s modern history of cultural developments like the Tsukiji Shogekijo, MAVO or the panorama pavilions. It even seems to me that most artists of the younger generation are only interested in their own daily lives.

- I guess it may appear old-fashioned. In the fine arts as well, works from the Taisho Period (1912-26) are not especially popular. Also, it is a sort of privilege of the young to place more importance on your own experience than on history, so I think it is OK to be that way. I think the history of theatre is the history of imagination and fantasy. The texts of ancient Greek theatre remain, but we don’t know today how they were staged or performed. So, we can only use our imaginations to visualize what the performances were like. If the history of theatre is an accumulation of such imaginings, it can be considered fantasy, or a history that we have created [in our minds].

In the case of fine arts, the works remain, for better or worse. Of course, more works have surely been lost than those that remain, but since we try to reconstruct the history from the works that remain, there is a certain clarity to it. And, because museums are functioning to a degree, they are trying to preserve the existing works for a thousand more years. But, theatre is always live. That is a big difference.

What has modernization been?

- In your new work Zero Hour: Tokyo Rose’s Last Tape , you take as your subject the propaganda programs that the Japanese military broadcast by shortwave to the American troops fighting in the Pacific during World War II. Those American troops came to call the female “voices” of those broadcast “Tokyo Rose.”

-

From 1943 to ’45, a group of Japanese-Americans gathered to work as the radio station “Radio Tokyo” broadcast programs to the Americans on warships in the Pacific, thus creating moments of happiness during lulls in the fighting when “voices” were sent from one closed room (the secret radio station) to another closed room (the compartments of the warships). However, because they were broadcasting propaganda, the Tokyo Rose figure was eventually condemned as a war criminal. The situation in Japan after the war led to that conclusion, but I believe there were indeed times when being able to hear those voices brought moments of happiness. Re-creating those moments is something that could only be done through theatre. The Tokyo Rose tapes remain, but they have been labeled an archive and only remain as such. Using our imagination we can imagine what the era was like and what the voices were like at those moments and what the experience of those moments was like, and using our creativity we can then express it on the stage. I think this power of theatre is unique and priceless.In fact, those Japanese-Americans in the radio station were made to read scripts that had been prepared for them and speak what they were told, so there was nothing that they were saying of their own will. In other words, they were being used like living translation machines. And, since there have probably been minorities used in the same way in throughout history, ancient and modern, in East and West, I believe that “Tokyo Rose” is in that sense a universal theme.

- It might be giving away secrets, so I don’t want to get into this subject in too much detail, but in order to create the voice of Tokyo Rose a state-of-the-art recording machine and acoustics technician were brought in from Germany played an important role. And the voice of Tokyo Rose that you actually used on stage was created by the musicians known as the Formant Brothers.

- I wrote the script with the ideas that perhaps Tokyo Rose didn’t exist and that she was in fact possibly no more than a virtual image born in the moments when there was a form of mutual communication between the announcers and the listeners. At that time, the voices on the recorded tapes (re-created voices) emerged as an important element. This is something that is true with photographs as well, but for me, in both art and theatre, re-created art is an important theme in my work. For this play I had Formant Brothers create the voice of Tokyo Rose. Normally, they are artists who create voices from scratch, completely synthetically, but since that wasn’t possible this time they used an actor’s voice as the base to work from. It turned out to be a difficult task, however, with lots of discussion about things like the difference between what Japanese consider sexy and what the American sailors would have considered sexy.

- Were you able to get it close to the voice on the Tokyo Rose tapes?

- No. It wasn’t similar to anyone’s voice. Since propaganda announcing is a war crime, the element of anonymity was very strong. So, we hear that in fact there were actually five of six people doing the Tokyo Rose broadcasts. All of them had different voices and accents, but when heard over the radio the difference wasn’t clear, so the fantasy grew until it became a single woman named Tokyo Rose. It is said that it developed into a strange phenomenon in which everyone [among the American sailors who had heard the broadcasts] was longing to meet the famous Tokyo Rose of their imagination after the war and many actually searched for her.

- With subjects like Zero Hour in your 1924 Trilogy, you are dealing with the pivotal period of Japan’s modernization from the 1920s and the 1940s. As an artist, it appears that you are taking on the challenging question of how to interpret Japan’s modernization.

- It is true that in a way I am trying to understand the modernization as part of my efforts to do theatre. Many artists, myself included, use the term “art for art’s sake” rather easily without too much thought, but in fact we don’t appreciate how many artists gave their lives to build the foundation from which we can speak these words. In the 1920s, European artists said that art is not connected to political ideology and art is for art’s sake because if they didn’t say [and believe] that, art would not have survived. Can we imagine the historical circumstances that led people who wanted to be artists to give birth to such an ideal? I have the idea that when things like the techniques of oil painting were imported into Japan from Europe, that ideal of art wasn’t imported along with it. So, what about theatre? I feel that finding out about that history [of theatre] might shed new light on [the history of] art as well.

The language of theatre and the language of daily life

- What are your thoughts about the language used in theatre? Today, most small-theatre plays in Japan use contemporary colloquial language, while there are almost no playwrights use the kind of poetic or theatrical language used by playwrights who influenced you, like Juro Kara.

-

In the case of Kara-san, he will say something lofty at one moment and the next moment he will use a commons saying, or he might use lines in a scientific tone that he follows with something completely contradictory, doesn’t he. In my case, with my photographs as well, I have no interest at all in “neighborhood” type photographs on some theme from daily life. In the same way, when I see people using the complex medium of theatre to depict some tepid theme from daily life, I get the feeling that I am being shown a dead-end picture of hopelessness. But, in fact they are probably doing their theatre with the desire to do something new and go places that no one has gone before. Rather, I feel affinity for attempts to make a flower bloom from the mud, or to show the blue sea that lies beyond the dirty backstreet, or attempts to show intense desire at a time when Japan wallowed in poverty. That contrast of hopelessness and aspiration will probably be revived again.

- Juro Kara was himself an actor and his words and their rhythm were probably things that came naturally from his physical sensibilities. In your case, you don’t stand on stage and speak as an actor, do you?

- I don’t. Kara-san surely wrote in his own words, like breathing in and out, but there are some people like Beckett who approached playwriting from the stance of a novelist. I believe there are a number of different patterns, but speaking honestly, I am still searching every inch of the way. I envision an actor delivering the lines as I write, but I don’t have a theatre company of my own yet, so I can’t test the things I write immediately.

- What type of writing method do you use when you write a text or script? Since you don’t have any actors on hand, I can’t imagine that you would be writing with specific actors in mind.

- Since I write alone, I don’t work through the medium of actors at all. For example, when I wrote my work Panorama on the subject of the panorama pavilions (circular buildings with realistic landscapes or cityscapes painted on the inside wall as a viewing attraction) that were popular from the Taisho into the Showa periods, the inspiration came from the Sakutaro Ogiwara short story Nisshin Senso Ibun (Harada Jukichi no Yume) (Another story of the Sino-Japanese War – Jukichi Harada’s Dream) and I included him as one of the characters in the play. I began by reading all the books I could find on panorama pavilions and Sakutaro and then wrote the play while trying to imagine things that he might say. In both Panorama and Zero Hour , as director I mostly left the delivery of the lines and the physical movement up to the actors. I still can’t control live bodies. People ask me, “Aren’t you interested in actors,” but that is not the case at all. This is something I want to think about from now on, including the possibility of creating my own company.

- In your plays, the “guide ladies” play a very important role as choruses or narrators. Using the guide ladies as a device, or medium or catalyst—you could call it a number of things—as an intermediary entity seems to provide another circuit of connection with the audience in addition to the traditional relationship between the actors and the audience. In the case where you had your guide ladies performing in the museum, their presence as a new medium inserted within the set relationship existing between the work of art and the viewer provided the potential to cause an instability in that relationship, or destroyed it, or cause a slight shift in it. This can result in the creation of a new space. That is the role I feel them playing.

- That’s right. The guide ladies are modern in appearance, but in substance they are like the Ukiyobikuni . They can speak like the professional storytellers of the pre-modern era or like announcers of today, and they are a type of media that must always belong to some type of profession or organization.

In the first work of my 1924 trilogy that we performed at the museum, the guide ladies would be giving very professional explanations of the art works of Marcel Duchamp and then suddenly switch to the taking style like the hawker of a cheap attraction in small show tent. In that way they serve as a presence that questions the validity of the modern art museum as a white cube showing the works of Duchamp in nicely designed displays. In Japan’s Meiji Period, I imagine that oil paintings may have been shown as attractions in places like show tents. Most probably, Japan’s first museums were places where a hawker would be there explaining the painting as an attraction. I believe that in Japan most new media, like photographs or radios or gramophones, were first shown as rare attractions in unrespectable-looking show tents like that. Wherever a new media appeared there was surely an element of performance involved. It was that element of fluctuating uncertainty that I wanted the viewers to feel.It was the same with the panorama pavilions. There was this building like a dark delivery room and it made you question, “Is this art,” or, “Is it a cheap attraction,” or, “Is it some kind of entertainment,” “Is it an amusement park?” It existed just in a short period of 20 years or so from the 1920s to the 1940s before movies came along and caused them to disappear from Japan completely. I feel that taking a good look at things like the panorama pavilion can give us an idea of what Japan’s modernization was. Until now I have worked in photography, which is a medium of replication or re-creation born of the period of modernization, so maybe I can project a different light on theatre from the perspective of the fine arts. And, that should also connect to projecting a new light on the fine arts from the perspective of theatre.

Looking to the future

- In one discussion in the past, you said that the end point is something you are afraid of. What about with theatre?

-

What I like about theatre is probably that it has no end point. Theatre (drama) is most often tragedy, isn’t it? There was a period when I used to wonder why plays so often had to end in such utterly tragic climaxes, but I decided that it is alright that way. Because, when you think about it, no matter how tragic the ending may be, a tragedy doesn’t end as tragedy, because I believe that the people put all their efforts into doing the tragedy and then they have a ritual to ward off evil and misfortune and re-direct that energy in a positive direction. In other words, in theatre time doesn’t move in a straight, linear way, so there is no end point, and I feel that perhaps this is why it continues to revolve endlessly.

- Thank you very much for your thoughts. Lastly, will you tell us what activities you have planned for the future?

- It appears that next year will be one of semi-outdoor or fully outdoor performances. Sometime soon I want to do a work about Kenji Nakagami. It may be the complete opposite of Beckett; it is a world with no end point.

For Zero Hour I used a beautiful stage set like a white cube, but next I want to do a gritty, unrefined play. Kenji Nakagami took the world of “the backstreet traveling in a trailer” in a gaudy decorated truck and ran it from Kumano [Shrine in central Japan] through the Northeast region (Tohoku) and ended up at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. One of the characters that appears in the trip is the Oryunooba that picks up in her arms all who were born on the backstreets. I believe that Kenji Nakagami is a writer who connects the deep localism of the backstreets with the intellectual exchange of globalism into one big circle. That is the appeal I feel in his work.At the same time, I want to continue doing series of works on the themes of replicating or re-creating arts and the relationship between the birth of new media and theatre. For example, before the birth of the media of printing, theatre was all handed down and communicated orally. So, when plays began to be printed, what did this new media change? When the theatre that had been communicated orally until suddenly became something that could then be shared through the written word, it certainly brought some changes to the form that theatre took, I believe.Presently, I have become interested in the oldest lithograph workshop in Paris and I am researching its history. Lithography was invented by Alois Senefelder, who was a playwright. Since he lacked financial resources, he invented lithography as a means to reproduce the plays he had written. That led to the printing of many plays, and later the method was used to reproduce musical scores. As it turns out, the use of lithography as printing method for art works was a by-product of the original use.I want to do work that is an accompaniment between works of reproduced art and theatre works.

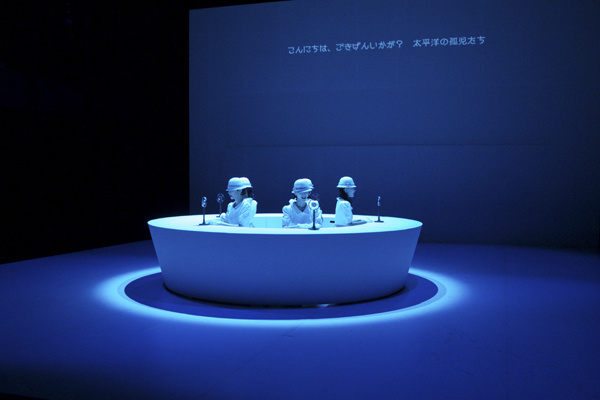

Zero Hour: Tokyo Rose’s Last Tape

(Jul. 12 – 15, 2013 at Kanagawa Arts Theatre – Large Studio)

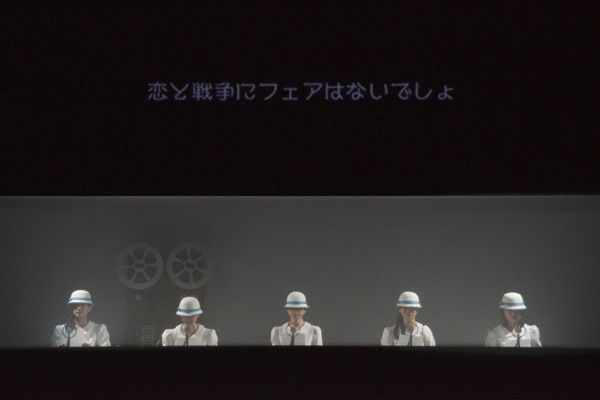

The Guide Ladies Project

(from Railroad Art Festival Vol.2 – “Station Theatre,” Art Area B1, Osaka, 2012)

My Grandmothers/YUKA

(2000年)

© Miwa Yanagi

Series of Fairy Tale: Untitled I

(2004年)

© Miwa Yanagi