- Seeing as I was a graduate student when I first had the opportunity to visit Toga Village, I can’t help but feel a bit nervous being here now to speak with you [laughs]. I also have many memories like serving as interpreter for the American director Robert Wilson when the 1st Toga Festival was held in 1982. This year the 9th Theatre Olympics is being held as a joint program by Japan and Russia. Twenty years have already passed since the second holding in 1999 when you were general artistic director of Shizuoka Performing Arts Center. Now that the Theatre Olympics is being held with your base of artistic activities, Toga Village as one of the main venues, I think this is a historical development. There are a lot of arts festivals today, but I think that The Theatre Olympics are different in that it is held with the artists working together in residence.

- We were originally planning to hold it with Toga Village as the sole venue, but then the request came from people in Russia saying they also wanted very much to have it, and that led to the Theatre Olympics being held jointly in two countries for the first time. When you say it is being held jointly by Japan and Russia, it might sound like it is a program of cultural exchange between the two countries, but that is not the case. What it is, is a program planned by the Theatre Olympics committee members from countries around the world being held as an international theater festival with venues in the two countries.

It is very interesting to have the same program being held in two places as different as the theater in Toga village where the population is less than 500 people and the palatial national Alexandrinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, a city with a population of 5.35 million people, and to still have the spirit of the artists to come and work together in harmony is wonderful. It is an opportunity to transcend the questions of scale and the number of people in the audience that can see the performances to come together to work with socially recognized artist who are known for the quality of their work. This is what makes theater and artists so amazing. The Theatre Olympics program aims to be a symbol of the fact that we can transcend the boundaries of ethnicity and national borders and wall and discrimination.

If you look at the Greek Tragedies that were create 2,600 years ago you will see, theater has always been thinking about things like how to act with other ethnic peoples, how to think about crime, what rules people need to keep in order to live as a community, the individual and a community, universal problems that transcend ethnicity. I believe that is why the Greek Tragedies and plays like those of Shakespeare have become the shared heritage of humankind that transcends nationality. Despite the fact that we have the word globalization today, the direction or orientation to create that kind of shared heritage anew has been lost in politics and economics today. That kind of orientation toward creating new rules of coexistence that can bridge this type of contemporary division is the theme of the Theatre Olympics this time, which is “Creating Bridges.” I want us to think about the need for this kind of value, this kind of spirit for people to share; to think about the rules for coexistence.

The Japan-side program that I will be managing consists of 30 performances (from 16 countries) with Toga Village as the main venue, but we will also use the outdoor theater in Kurobe City, where the factory of the Chairman of our TOGA Asia Arts Center support committee, Tadahiro Yoshida (Member of the board of YKK) is located, and the hall at Unazuki Onsen. The opening program is King Lear and performing in it will be actors from Germany, Russia, America, China and Korea Rep. There will also be actors from various countries performing in the production of The Trojan Women starring Theodoros Terzopoulos. The artists naturally have nationalities, but unlike the sports Olympics, they do not compete as representatives of their countries. I believe that the role of the arts is to transcend ethnicity and nationality and pursue our shared universality as human beings. - Would you tell us more about the TOGA Asia Arts Center support committee?

- Even if artists have ideas, they don’t have the power of money [laughs]. They can’t do things unless they have people to support them. When we thought about the future of Toga and created the TOGA Asia Arts Center (*) as a base for the creation and education of artists involved in Asian performing arts, people like the governor of Toyama Prefecture, the mayor of Nanto City and people in enterprise like Yoshida san got together and said they would support us. It is because of this support that we are able to do things like the Theatre Olympics this time. We are very grateful for the way the support committee brings together the public and private sectors. Soka Gakkai (lay organization, based on Nichiren Buddhism) donated free of charge some land that they owned in Toga Village and we built a new residence facility on it. I believe that young theater makers in Japan should have more faith that there are people here who will support them in this way if they approach them with plans of things they want to do and the ideals behind them on a level that they can understand.

- The Theatre Olympics were founded in 1993, a quarter of a century ago. Do you feel that theater and the state of the theater world were different then for today?

- There were two aspects to our launching of the Theatre Olympics. One was the fact that entering the 1990s it was getting harder for internationally active theater people to do theater. At the time there were theatre people who were recognized internationally and as artists their work gave people spiritual pride, and as such people thought that they were valuable asset of society, intellectually, artistically and traditionally. So, they were respected even by people with different mindsets and positions, and there was a consensus in society that they should be supported as a valuable asset to everyone. But with the spread of globalization, there came a trend to think that economic stability for the country was more important than that spiritual value and it became harder for theater people to do theater. In answer to that problem, we thought that artists should join together to do something about this global issue.

The other aspect was the situation in the world at the time. In 1989, America’s President Bush and the Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev declared the end of the Cold War, and with events like the reunification of Germany in 1990, the world seemed to be headed toward a more peaceful era. In fact, however, war broke out in the multi-ethnic former Yugoslavia and in other places in the world were plagued with inter-ethnic struggles and territorial disputes. The Cold War era had been one of conflict between the communist nations and democracies with capitalist economies, but since the two sides had been divided by ideologies and values, so although there were some problems, the societies still held together on that basis. When that social order fell apart, it resulted rather in an increase in conflicts. It is similar to the current problem in the EU. At the time, when the Greek theater director Terzopoulos (current Chairman of the International Theatre Olympics Committee) came to Japan, he said when the Cold War ended they thought Europe was headed toward peace, but it didn’t happen that way. He said there was a terrible situation with things like ethnic strife, and it lead to huge numbers of refugees. Amid the political instability, people were hurt and losing hope. And he concluded that it was frustrating for artists to be unable to do anything in this situation. That being the case, he said we should band together as artists and do things with a kind of love that transcends barriers of nationality.

Although it isn’t directly related too the Theatre Olympics, at the time I got a telegram from a theater maker from Sarajevo saying that they wanted me to do a play there in Sarajevo, and that they would come and pick me up in a military plane. The awareness that it is important to do theater during a war is amazing. Historically, Europe has been a place where there is a strong belief in using theater to think about fundamental issues of living in a society, like what is a human being, what is a nation, what is crime, so during the conflict at that time they wanted to use theater as material for thinking about what the new world order should be like. In fact, Susan Sontag did go and do theater there, but for some reason I lost contact with them somewhere along the way and ended up not going. - Why are artists able to work together that way, even though their backgrounds and means of expression are different?

- For a child, the place where they are born is their hometown, but as we grow older, the place where we raise our families or the place where we grow old and eventually die is our hometown. But, I believe that artists are people who by nature don’t believe there is a place where they can live with a sense of security a hometown implies. A hometown is a place you can go back to, a where you can feel safe, but for an artist, I think that place is probably in the heart. Perhaps I would say that home is a place where hearts connect by being moved by something, even if that is a somewhat lonely concept. The artist works hard to create works that a lot of people will come to see. But, usually it doesn’t work out that way [laughs].

Artists like that can work together because they believe not in things you can see, like monetary worth, family, high and low, rich and poor, or man and woman, but in a shared belief in some kind of human value that can’t be seen. So, if you don’t have the desire from the beginning that you want many people to share that feeling, something like the Theatre Olympics would never be possible. You don’t do theater because you have a theater, you don’t get ideas for projects because you have a publicly funded grant. - The Theatre Olympics began in Greece and gradually spread and grew in scale.

- It was first held in Delphoi, a place with a population of only about 3,000, chosen as a holy place in ancient Greece of the kind where Oedipus received the fateful prophecy, in order the strengthen the spiritual resolve of solidarity. After that, there were voices from the government saying they wanted to give it financial support, and with that it gradually grew in scale. With that, there was the need to work with people like politicians or entrepreneurs who could provide leadership, but then there was the fear that the original spirit of the Theatre Olympics might be forgotten. But there was also a trust that the final outcome would be good, in the spirit of the words attributed to the Zen Master Ikkyu that the roads toward the mountain’s summit may be many but in the end they all lead to the same view of the pure Moon above.

But this time, some members of the International Committee said it would be good to return to the original spirit of the Theatre Olympics and do it in a place like Toga where the artists could reconfirm their solidarity and think about what the problems are now and what the world needs now. In Toga Village there is the foundation that SCOT has built up over the years, but because the theaters are small and the lodging facilities are limited, the audience it could draw would not be in the tens of thousands. So, the scale might be small but it would be just right for exchange between the artists and thinking about a lot of things. - Ever since your Waseda Shogekijo work was first introduced at the Théâtre des Nations Festival in Paris in 1972, you have been a pioneer of overseas activities for some 45 years. SCOT productions have visited some 33 countries and your Suzuki Method of Actor Training has been taught in many arts schools, ranging from The Juilliard School in the U.S. to China’s Central Academy of Drama.

- It wasn’t to advertise Japan that I went overseas. If asked why then did I go overseas, I would say that it was to show our work to professionals overseas who are thinking on the same level about theater, society and the human condition. If Constantin Stanislavsky had wanted to see what we do, I would have wanted him to see our work, and since Jean-Louis Barrault invited us I went to Paris to show our work to him. I didn’t go to show our work to people overseas who like Japan but, while the background of our work is Japan, I went to show it to people who have the eye to see the universal aspect of the art of theater.

The important thing is to find people from other countries that we can work together with, but too often the trend today is to go overseas because you have received funding from the government or because a friend gave you an introduction to someone overseas. What’s more, such people go overseas on the pretext that what they are showing is Japanese culture. They are not showing their work as artists but as Japanese advertising Japanese culture. It is no good if the audience you are performing to there is made up only of foreigners who like Japan and overseas Japanese.

- So it is just as a form of contemporary exoticism that is taking them overseas, isn’t it? Neither the people that are inviting them and the people who are accepting the offers have a more serious sense of purpose. However, Toshiki Okada of chelfitsch did something different to thwart that level of exoticism, when he was commissioned to do a new work at Kammerspiele in Germany, he made sure it wasn’t the exoticism they had hoped for by doing a collaborative work with Thai artists, and he had it performed in Paris in Thai. Of course, that was an exception, and in the case of most young theater makers today they seem to be looking inward and have little interest in working seriously abroad in the real sense. On another note, I would like to ask you to talk about new overseas developments in Asia. I haven’t been there yet but in 2015 an outdoor theater was built for you in Gubei Water Town north of Beijing, wasn’t there?

- A famous Chinese developer built an outdoor theater with a view of the Great Wall along with a residence facility and studio on land belonging to the Beijing municipal government. Every year in April I go to teach the Suzuki Actor Training Method there. We also did rehearsals for Kachi Kachi Yama and Dionysus there for two or three weeks. The Great Wall is of course a famous sightseeing destination and some six million people visit there annually. And since they want to make it one of China’s representative international spot, they told me I can do any type of project I think would be good there. The developer wants the area to be used strategically for cultural purposes, but he didn’t want it to be just a theme park, saying that it had to be for art, and it is interesting that he said it didn’t need to be a Chinese artist but it could be a Japanese artist like me.

- Do you use Chinese texts for your plays there?

- Yes. Many people misunderstand the fact that once a work is translated into the local language, whether the original is a Greek Tragedy or Shakespeare, once translated it becomes that country’s play. Every language has tradition behind it, and since it is spoken in daily life it relates immediately to physicality as well, so as soon as a play is translated into Chinese, it belongs to the Chinese people.

- In Toga Village you have people coming from Indonesia to learn the Suzuki Actor Training Method, and in 2018 you had a 3-language performance of Dionysus done by Indonesian, Chinese and Japanese actors. It was also performed at an outdoor theater in Jogjakarta, Indonesia. What was the reception like there?

- We did it in three languages, and nothing like that had ever been done in Indonesia before. In short, if all the actors are trained in the same method and are thinking the same way, it is possible to do quite interesting collaborative work with Indonesian actors. So, you don’t simply have to learn from what is being done in Europe or the United States, if you have a common starting ground you can build on, it will be OK. It was an experience that showed me if you have a shared set of rules and principles that transcend ethnicity and nationality, you can collaborate and do quite good work.

Until now, there was an idea in Asia that you could learn from European theater, but instead of doing that, we now have changed to an idea that we can do things together if we have a different working ground of our own. When you think about sports, there are clear-cut rules that mean players from any country can play together in football or baseball or Sumo wrestling or any sport. So that means that as long as you the same rules and you train properly under the same system, everyone becomes equal. Every country’s people have amazing potential, so there is no reason to feel culturally inferior. - Lately we see a lot of so-called international collaborations in theater and dance, but what you are saying is that in order to do something that isn’t a collaboration in name only with no lasting meaning, you need to have shared working principles from the beginning, don’t you?

- For example, in football if there are players from a number of countries playing you don’t call it a collaboration, and you don’t call it a joint team. Also, Japanese theater doesn’t become international just by doing an international collaboration.

- Do you mean that people should pursue principles that anyone can share in, and to think seriously about that?

- Yes. That is what they have to strive for. We will be doing a production of Cyrano de Bergerac in Russian and Japanese, and until now I have done productions in Japanese and English, Japanese and German and also productions in Chinese. Why are we able to do this? It is because everyone involved shares the same approach to theater, does the same training and knows the ideas behind the Suzuki method. It takes a lot of time and effort to get to this points of sharing the same objectives and training, but once it is achieve we all stand on the same footing and can work together. It is a completely different issue from whether a work is interesting as Japanese theater. My nationality is Japanese, but my aim is not to do Japanese theater. I am doing Suzuki theater. I say we have Noh, Kabuki, Takarazuka Review and Suzuki theater [laughs]!

The rules of Suzuki theater have become international, the question is not whether individual plays become popular or not. When you look at the individual works, some are good and some are unsuccessful. But since there is a shared knowledge of the rules under which they are made and the ideas behind the works, whether they are done in Russia or China, the lighting, the movement the voice projection tell you immediately that it is Suzuki theater. When we did a production with Russian actors at the Moscow Art Theatre, I was told, “Even though it was Russians doing it, it was still Suzuki,” and it is the same as football—no matter who plays it, it is still football, and that is actually an amazing thing. - As it was with Stanislavsky, it is surely because, although it has the Suzuki name to it, it is a method by which the physicality, the movement is properly controlled so that it projects the play to the audience it is intended to reach, and the lines of the script tell the story in a way that clearly reaches the ears of the audience it is intended for. That is proper acting, and I believe it is my duty to point out that you, Tadashi Suzuki, created a proper method for doing this.

- It can be seen that way. That is why professional actors from 16 countries come to Toga for training in my method, and they say it is very helpful for them. None of these people think they are doing Japanese theater, it has spread to these countries because they find it useful as basic theater training. There are even some people I don’t know who are teaching the Suzuki Method somewhere [laughs].

- Along with your method for acting, you have created stage adaptations of Western theater ranging from the Greek Tragedies to Chekhov that communicate a worldview. Another thing you have done is to take Japanese novels or songs as bases for theater that does not belong to the general categorization of “Japanese” but has been thoroughly worked by you into your own personal world of theater. Recently you have also been actively posting a blog that shows your stage directing notes and daily activities, and you have published stage scripts with detailed explanations of the contents.

- Back in our day, we had people from other fields coming to see our works that they found interesting. Some examples are the novelist and critic Shōhei Ōoka, Japanese literary scholar Donald Keene, critic Shūichi Katō, poet and literary critic Takaaki Yoshimoto, architect Arata Isozaki and well as the Nobel Prize-winning author Kenzaburō Ōe. That led me of necessity to study up on their areas of expertise, and we would talk at the cafes. When we first did our production of The Trojan Women at Iwanami Hall, Kabuki actor Ennosuke Ichikawa came to see it, and actor Hisao Kanze, who played the role of Menelaos, is said to have asked how we were able to act the way we did. When Kabuki actor Tamasaburo Bando saw our production of On the Dramatic Passions II he said he wanted to borrow from the vocal presentation technique of actress Kayoko Shiraishi when he played the role of Nanboku Tsuruya, so I sent him a recording of her performance.

It is from the things you learn from people like these from the other arts that gives you new knowledge to draw on that leads to the birth of new of looking at theater. This is a stage that today’s young theater people haven’t been through. There is now a theater research institute in the New National Theater, Tokyo, but not much can be accomplished by simply inviting acting instructors and directors from abroad to give lectures. Creators need to begin by studying and gaining an understanding of Japanese literature, philosophy, aesthetics, music sociology, economy, performing arts and the traditional arts. - In that sense, I think it is important that you are now talking about your own creative activities, and I think that the Toga Village Theatre Olympics is an increasingly important program. From the era of the Toga festivals, your practice of not interfering during the course of the festival left us free to talk about whatever we wanted, and admittedly a lot of it turned out to be useless talk we were doing [laughs].

- That is important, however. Theater can provide the kind of environment that gathers people from diverse backgrounds to talk together. By watching the same performances, those people have the opportunity to discuss and share their different perspectives on what they have seen. That becomes an opportunity for your perceptions and misconceptions to be corrected. We had a salon atmosphere where knowledgeable people from various fields could come together to see the same things and then discuss about them and in some cases realize where our perspectives were still limited, or where we needed to do more studying and thus grow with objectivity. It may be that those kinds of platforms are too few today.

- There is a trend for young Japanese theater makers today to do theater for the purpose of self-acknowledgement. And because that is what the audience wants too, they react to strong physicality, strong theatrics and strong words that may negate their own values as a form of violence.

- There is that aspect. I did a theater course for young theater makers at Kichijoji Theater, and I found that they were all intelligent, but they lacked energy. When we were young there was a tendency to be rebellious, but a lot of us gathered together and built a theater shack with our own hands and did theater like we wanted to. And there were people then that were interested in that kind of thing, but today there aren’t people doing things like that or interested in it.

- I went to the “SCOT Summer Season 2018” last year, and on the final day I had the opportunity to see for the first time the talk where you took questions from the audience at large, and it surprised me. You were answering in careful detail some strange questions from young people that I myself would have had a hard time not getting angry at. From that kind of dialogue, I felt that the existing foundations were being shaken to the roots within those young people. From the 2013 SCOT Summer Season, you stopped charging the usual admission fees for the audiences and switched to a voluntary donation system, and I felt that after that there were many more people in the audiences that had never seen SCOT productions before, many who weren’t used to seeing theater and hadn’t been to Toga Village before, especially young people and visitors from other Asian countries. There is a production of Greetings from the Edge of the Earth (Sekai no Hate kara Konnichiwa) at the outdoor theater that is popular for its fireworks displays, and it has become known among young people today by the abbreviated title “SekaKon.”

- It costs a lot for the public transportation to get to Toga, so in order to enable people who want to experience and are interested in our activities to come more freely, we decided to make the performances more open to them. Since we made it a voluntary payment system it is that much more open to them. There are some difficulties, but we are doing it anyway. We have now seen people like one who quit the National Defense Academy of Japan and came to Toga wanting to join SCOT, so things are gradually getting more interesting.

I am asked about our future plans for Toga Village, and since we have recently expanded our facilities, I want to see us start a school that will gather students from around Asia. Already, the National University of Singapore and China’s Central Academy of Drama are sending students here each year. And although it will be a drama school, I don’t want to be teaching students with no previous experience from step one, I want to gather students who have a basic foundation in theater. I want us to teach the Suzuki Actor Training Method and make theater productions and then critique them among us. I also want to bring in economists from Asia and have them gain a global perspective by thinking together with them.

It is also the case with theater festivals, but I think the important thing is that we build a network of international artists together without borders. You can’t create such a network unless you speak about your ideas and what you are fighting for. I want that to be one of the fundamental things we teach in our school. - In this time of so much division, what will be the strength of artists who come together in such a network of collaboration?

- I don’t know. But, interesting things will happen. In the Theatre Olympics we have been invited to perform Macbeth in Sardinia, and the local government is sending a chef of Sardinian cuisine along and told us to enjoy the cuisine at Toga Village. If the venue were Tokyo, you wouldn’t see these kinds of very human touches occurring. It is Toga Village that inspires these kinds of things that build interesting relationships.

- Perhaps it isn’t my place to comment in this way, but I think that there is a sort of unpredictable anarchy to Toga Village that makes anything possible. For example, even if the electricity goes off and it is completely dark at night, Toga Village is the kind of place where that can be forgiven and accepted. In the era of the Toga Festival, perhaps because I was younger then, it was fascinating how an isolated place like that could take on such a festive air. But now I feel that Toga has an anarchy that is connected to the world at large, there is a lot to learn there and theater makers and the young audiences always find something to take away with them from their experiences there. Like the admission system now, I felt it is truly a place where everyone is at their liberty to give and take as they will. I am really looking forward to the kinds of collaborations that will come out of it.

Finally let me thank you for all the valuable time and information you have given us today.

9TH THEATRE OLYMPICS

Owing to the global development of the system of information and communication, people everywhere can now feel and know closely about other than their own cultures. Compared with the olden times when people experienced everything on the spot and thus nurtured wisdom required for coexistence with other human beings, our world is permeated by something completely new, a change which enables us to know and understand things without actually ‘being there’. The change has been brought about by means of thorough exploitation of ’non-animal’ energy (electricity, oil, nuclear power etc.) and is necessarily going to increase in the future.

It is, however, dangerous to trust this ‘non-animal’ energy too much, which claims to connect people with each other with maximum speed. For it can lead to the forgetting or weakening of the rich possibilities of ‘animal’ energy stored up in the bodies of human individuals. Human cultures have bloomed and borne fruits through the refined uses of ‘animal’ energy. It is precisely in this way that performing arts, such as theatre, dance, and opera, have become a heritage of humankind irreplaceable by such media as television or film.

The same applies to sports. Both performing arts and sports provide the ground for better understanding of and deeper caring for human beings by means of bringing people together to the very spot where they are taking place. No matter how enormous and necessary the system of communication by ‘non-animal’ energy may become for our actual life, it would be suicidal for humankind to forget or ignore the values embodied by performing arts and sports.

Needless to say, the way people train, refine, and enjoy the ‘animal’ energy varies from nation to nation, from place to place. But it is those very differences that preserve and assert the cultural identities and raisons-d’être of each nation. The greater the amount of ‘non-animal’ energy, which tends to reduce our lives to uniformity, the greater the contribution which performing arts are expected to make to the quality of human life in the future. The significance of cultural projects in these technological days lies in the fact they help to make possible shared experiences of similarities and differences inherent in various nations.

It is the belief of the International Committee of the Theatre Olympics that, as we enter the 21st century, the powerful existence of performing arts must prove a sign of profound encouragement and hope for truly global communication.

Suzuki Tadashi

Artistic Director

Tadashi Suzuki/SCOT

https://www.scot-suzukicompany.com/en/

Theatre Olympics

After the formation of an international organizing committee consisting of world-renowned directors and playwrights such as Suzuki Tadashi, Theodoros Terzopoulos, Robert Wilson, Yuri Lyubimov and Heiner Muller, the Theatre Olympics was were founded in Delphoi, Greece in 1993 as a performing arts festival. It is unique in that international artists work jointly to plan collaborative productions, and in addition to performances of works of performance arts, educational programs are also conducted. Until now Theatre Olympics have been held in 1995 in Greece (Delphi, Athens and Epidaurus), in 1999 in Japan (Shizuoka), in 2001 in Russia (Moscow), in 2006 in Turkey (Istanbul), in 2010 in Korea Rep. (Seoul), in 2014 in China (Beijing) in 2016 in Poland (Wroclaw) and in 2018 in India (New Delhi), etc.

The 9th Theatre Olympics will be held jointly in Japan and Russia. The Japan event (artistic director: Tadashi Suzuki) will be held from Aug. 23 to Sept. 23, 2019 at venues in Toga (Toyama Pref. Toga Arts Park), Kurobe (Unazuki International Conference Center “Selene,” Maezawa Garden Open Air Stage (YKK)), with 30 works (from roughly 16 countries) performed. The Russian event of the 9th Theatre Olympics (artistic director: Valery Fokin) will be held as part of the “Russia Year of Theatre” initiative of President Putin. It will run from September to November at the Alexandrinsky Theater of Saint Petersburg as the main venue (plans calling for performances of works from roughly 30 countries and works by 15 Russian companies), and there will be a “theatre marathon” running from January in Vladivostok to November in Kaliningrad.

https://www.theatre-oly.org/en/

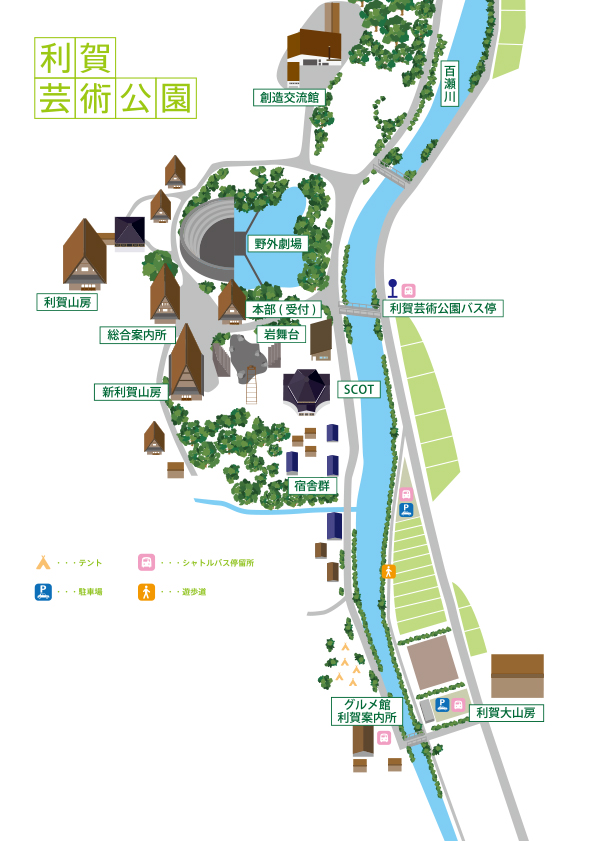

The Toga Art Park of Toyama Prefecture

In 1973, the Toga Gassho Culture Village was established as a means to encourage a growth in visitors to the Toga area by relocating five of the remaining traditional “gassho-zukuri” type thatched-roof A-frame farm houses of the village. In 1976, Tadashi Suzuki converted two of these and re-opened them as “Toga Sanbo” theater facilities. In 1982, the Japan Performing Arts Foundation was founded and a new outdoor theater constructed to hold the 1st Toga Festival. Since then, further local development projects and the development of the arts facilities led to the establishment of the Toga Art Park as a Toyama Prefectural facility.

http://www.togapk.net/

“Toga Sanbo” theater

Toga Open Air Theatre

Map

*TOGA Asia Arts Center

Taking advantage of the extensive theater-making facilities of the Toga Art Park in Toyama Pref., this arts center founded in 2012 with Tadashi Suzuki as its representative strives to be a base for the rapidly growing world of diverse Asian performing arts with the themes of creation and education primarily in Asia. Its main programs are performances by international theater company International SCOT, the international Suzuki Actor Training Method program, Asian international theater camps for creating and performing works in collaboration with China’s Central Academy of Drama, Korea Republic’s Chung-Ang University, Vietnam’s Hanoi University of Drama and Cinematography and other organizations, outreach programs for children and various types of conferences. To help support community development programs employing the performing arts, the TOGA Asia Arts Center Support Committee was launched in 2013 with members of the public and private sectors including the Governor of Toyama Prefecture, the Mayor of Nanto City and representatives of industry in Toyama Prefecture.

*Suzuki Method of Actor Training

Based on Suzuki’s belief that the fundamentals of a stage actor’s training are the ability to concentrate on the breathing and the lower body, this system of actor training is aimed at stimulating these physical senses that would otherwise deteriorate in the course of daily life so that the actor can control his/her body effectively on stage. From the 2nd Toga Festival in 1983, Suzuki started the international Suzuki Toga Summer Camp to train actors in this method. With this, actors began to gather from countries around the world very year to train at Toga Village. The method has been taught at educational institutions such as the University of California, The Juilliard School and Columbia University and theater companies around the world. When the Stanislavski System of actor training that had been dominant in the United States as training for theater based on achieving theatrical realism was seen to be no longer suited for the theater trends after the 1960s, the Suzuki training method soon replaced it as an effective alternative.

SCOT

King Lear (2009)

at Open Air Theatre, Prambanan Temple (2018)

at Great Wall Theater in Gubei Water Town, Beijing (2015)

SCOT

Dionysus

SCOT

The Trojan Women (2014)

SCOT

Greetings from the Edge of the Earth (2015)