M1 CONTACT

Striving to develop and spread contemporary dance in Singapore

- The M1 CONTACT contemporary dance festival for which you serve as artistic director was launched in 2010, and in 2015 it was held from November 26 to December 12. The festival was unique in that it was composed of seven distinct programs (*1), isn’t it? Would you begin by explaining to us the overall program?

- The Continuum Dance Exchange is an educational program for young people who want to study dance at schools in the countries of Asia with the aim of becoming professional dancers. We had performance by students from Singapore’s School of the Arts (SOTA) and Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts and Lasalle College of Arts, from Australia’s Victorian College of Arts, South Korea’s Korea National University of Arts and New Zealand’s New Zealand School of Dance, and then we had classes together with them. It is a platform for sharing awareness of issues common to Asia and exchange opinions and do research regarding ways to improve dance education in each country.

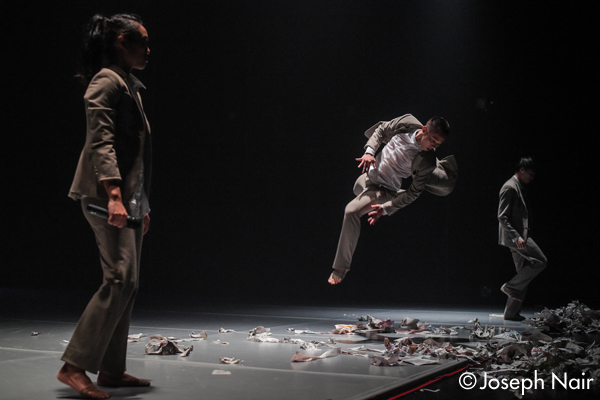

The name of the DIVERCITY program combines the word diversity and the word city, and it is a showcase program that presents the work of young companies from around Singapore, with five works performed each day of the festival. And the T.H.E. Dance Company – Triple Bill From East to West program is one in which choreographers from Asia and Europe choreograph pieces for the company, and this time the choreographers were myself, Iratxe Ansa from Spain and Jecko Siompo from Indonesia. - At the festival this time I first saw the Asian Festival Exchange program. Participating from Japan were Mikiko Kawamura and Naoto Katori. True to the “Exchange” in its title, it showed a program that displayed tie-ups with festivals around Asia including Japan’s Yokohama Dance Collection and Fukuoka Dance Fringe Festival, as well as South Korea’s Seoul Performing Arts Festival and Malaysia’s d’MOTION International Dance Festival.

- Yes. Katori performed a duo piece with Malaysia’s Amy Len. Kawamura choreographed a piece for our second company. I believe that the important role of this program is to enable young Asian dance artists to meet each other and learn about each other’s thoughts and ideas. I believe that through creation we can come to understand things beyond the dance works themselves, such as how other artists perceive the body and how they create movement, and the cultural background and ways of looking at things that lie behind their art. I intend to keep increasing the number of festivals we work in cooperation with.

- The SEA Choreographers’ Showcase invited artists from around Southeast Asia.

- We presented works by Singapore’s Daniel K (Daniel Kok) and Indonesia’s Andara Moeis and Moh Hariyanto. To change yourself you have to change the things around you. This is especially true in the Southeast Asian region that Singapore belongs to. That is why I believe that it is important for us to use our festival to get to know more artists from Southeast Asia.

- The work presented by Andara Moeis was one that she created with a Japanese dancer she met at the dance school P.A.R.T.S. operated by Rosas, wasn’t it?

- That’s right. With these links between Indonesia, Japan, Belgium and Singapore, it really feels like the world is a small place, doesn’t it? [Laughs].

As for our International Artist Highlights program, it is one in which we present performances by artists of the very highest level that we invite from around the world. This time we invited productions by Australia’s Chunky Move, South Korea’s R.se Dance Company and works by Spain’s Iratxe Ansa. And, our M1 On Stage program is for artists selected from open applications, and ten are selected (seven from open applicants and three guest artists) and divided two sets of performances. From among these performances, some are invited to festivals in other countries, and this time ones were invited to Spain’s Masdanza festival, Malaysia’s international dance festival d’Motion and Seoul’s New Dance for Asia festival. - Would you please give us an outline of the festival? I will ask you more about it later, but you returned to Singapore from Spain in 2007 and started your own company the next year. Two years later you started the M1 CONTACT festival. That seems like a rapid development.

- Because, there was a need to work rapidly. When I returned to Singapore, there was still the general feeling among the audience that contemporary dance was difficult to understand and hard to enjoy. I knew that my company’s activities alone were not enough to change that image. This situation wasn’t one that existed in Singapore alone, and I believed that we needed create a platform that would provide an opportunity for not only Singapore but also the surrounding countries in Southeast to think about contemporary dance from a more international perspective and engage in educational activities. So, when I created M1 CONTACT I already had the vision of launching an international festival. Because, when people encounter outstanding artists they become inspired and want to communicate that discovery to other people. At the same time, I am always asking myself what I can learn going forward.

- How to make a program that results in a good festival is certainly a difficult question. It isn’t enough today simply to invite famous companies to perform. It has also become important to have sub-programs that provide opportunities to think and learn about dance and promote exchanges.

- That’s right. Until this last festival I had avoided inviting famous companies, but this time I invited Australia’s Chunky Move. That was because I think their work is good, and not just because they are a famous group. By inviting companies to our festival, I want to expand our connections with artists that it will be possible for us to work with in the future. I think that is a very important thing for countries in Asia.

- The current artistic director of Chunky Move, Anouk van Dijk, is Dutch and one who has been invited to festivals in Japan in the past. She is an artistic director that Chunky Move chose through an open selection system, and we hear that she dissolved her own company in the Netherlands to move to Australia. It was surprising, and I think it shows that the positions of Europe and Asia are changing.

- Certainly it is true that Asia is changing rapidly. In Southeast Asia, where Singapore is located, we are closely surrounded by many countries, but we are seven hours away from Japan and six hours from Beijing. It is also a long trip to Taiwan, and thus we haven’t interacted very actively with these countries. But, things need to change. That is why we have now established connections with Japan, China, South Korea as well as Australia and New Zealand as well.

- Looking at your festival’s programs, and now hearing what you have just said, I can see that the Asia you envision has been growing in concentric circles. First it encompassed your neighboring Malaysia and the nearby countries of Southeast Asia, and then it expanded to the northern Far East countries of Japan, China and South Korea and the countries of Oceania. It appears to be a very strategic expansion. By the way, could you tell us about your festival’s budget.

- Our dance company and our festival are run by the same staff of five people and two part-timers, and the company and festival are both run off the same annual budget. The budget consists of SGD520,000 (approx. USD380,000) from Singapore’s National Arts Council (NAC) and SGD80,000 (approx. USD59,000) from M1. M1 is a telephone company that supports the arts through a number of programs. The rest of our budget comes from ticket sales and grants from overseas foundations like the Japan Foundation. We also get support in the form of performance and studio space from the Esplanade complex and the theater of the National Art Museum and the Lasalle College of Arts, etc.

The Singapore Dance scene in the 1990s

- I would like to ask to tell us about your own background. When did you begin dance?

- I was born in Batu Pahat, Johor in Malaysia in 1973. It is a very small town with little association with the arts, and at school I got mainly a regular education. When I was 15, I joined the Batu Pahat dance company, but it was a troupe for the Chinese-Malaysian community and not a professional company. Since Malaysia is a multi-ethnic society made up of ethnic Malays and immigrants from China, India and other ethnicities, in each of these communities the people learn their own traditional dance.

- What type of dance did you learn in the Batu Pahat dance company?

- In theory it was contemporary dance incorporating some elements of traditional Chinese dance, but in fact it was mostly like the dance of Merce Cunningham and others. It was exciting for me because it wasn’t simply a matter of learning traditional dance, but rather it was based on the idea that culture is something that introduces new element to build toward the future. The Batu Pahat dance company’s leader, Tan Lian Ho, influenced me greatly. I was 15, which that is a point in your life when you are beginning to search for things like the meaning of life, and for me the way the people of that company approached the world through dance was tremendously appealing for me, so I immersed myself in dance.

However, in Malaysia at that time it was very difficult to become a professional dancer, in 1991, just before I turned 18, I moved to Singapore and joined the Singapore People’s Association. There I studied a variety of different kinds of dance, including traditional dance, jazz dance, hip-hop, ballet, Indian traditional dance and Malay traditional dance. For me, it was my first professional dance training, and I was able to build a dance background for myself there. However, more than being toward the aim of creating new culture, it felt to me like a process of performing dance that would please the general public. I believe that it also had an aspect of helping to connect people in a political sense. But, I wanted to do more artistically oriented dance, so eventually I quit studying there after a little less than a year. Just at that time, the artistic director of the Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT), Antony Then, had seen me at a workshop and asked me if I wanted to join SDT, so I decided to do it. - SDT is one of Singapore’s representative companies. Recently it presents largely ballet-based productions.

- Yes. I had no real foundation in ballet before going there, so that is where I got my ballet training. At SDT they do two seasons each in ballet and contemporary dance works. There I danced in works by Jiri Kylian and Ohad Naharin and others and I really enjoyed it. I was a member of SDT for 11 years.

- What kind of dance was popular in Singapore at that time?

- Singapore’s dance companies at the time were SDT, also the Dance Dimension Project (name changed to ECNAD in 2001), the Arts Fission Company and others. Also famous internationally was Goh Choo San (1948-1987). During his career he was Associate Artistic Director and Resident Choreographer at the Washington Ballet Company.

In Singapore in the 1990s, unlike today, my impression was that a lot of American companies were invited to perform here. A personal favorite of mine was Taiwan’s physical theater company UTheatre. I especially liked their works inspired by the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski. - When you were in Singapore in the 1990s there was a new wave of performing arts brought about by Alvin Tan’s Necessary Stage founded in 1987 and Ong Keng-sen’s Theatre Works launched in 1988. Also, with the Singapore Arts Festival launched in 1977 (Low Kee Hong serves as artistic director since 2007) and other activities, the arts scene was thriving. Did you have any contact with these movements?

- Since I had come to Singapore in 1991, I assumed that level of activity to be the norm. But I only began to have interaction with Keng-sen and Kee Hong after I returned from Spain in 2008 and had founded my own company. It was from that time that I became keenly aware of Keng-sen’s work and found it very stimulating. As for Kee Hong, he is the director who has been most actively inviting my company’s performances to his festival.

In terms of dance, the 1990s was a time when ballet and neo-classical dance was popular. Companies like Dance Dimension Project were mainly presenting cross-disciplinary work. Also, since SDT was founded in 1988, it was still a young company when I was with it. SDT was the first company in Singapore to employ dancers from the general public, and there were seven dancers (today there are more than 30).

The first piece that I choreographed was one in 1992. It was an omnibus work in which six choreographers. For me, the experience of choreographing is something that helps me develop as a performer. Because, it makes me think about how to communicate my ideas to dancers and to the audience and it also makes me pay attention to lighting and music.

The encounter with Nacho Duato

- After being an active member of SDT, what was it that made you go to Spain?

- In 2002, when I was thinking it was about time to take the next step in my career, there were some performances in Singapore by Nacho Duato’s national dance company Compania Nacional de Danza from Spain. It was a real shock for me. The vocabulary of movement, the way they used music, it was all wonderful, precise, and also passionate. I told the manager of Nacho’s company that I wanted to dance in it. I was told that there would be auditions the following year and I should come to audition, but I was so excited by what I had seen that I couldn’t wait and the next day I was knocking on the door of Nacho’s dressing room. I went straight to him and said I wanted to dance with his company, so please watch me dance. Then he gave me a solo audition the next day. I was made to stand on stage with some other members of the company, and while Nacho was teaching me a piece of choreography to perform, the others were involved in creation behind us at the same time and they danced with me, which was a very special experience.

- So then you became a member of the Spanish national dance company and eventually became a principal.

- Yes. The only other Asian in the company was the Japanese female dancer Tamako Akiyama, who had joined the company before me. It is a fact that because of that appearance element, there were some expectations regarding me from the beginning. But if I didn’t achieve the proper strength as a dance there would be no place in the company for me. At the time, Nacho was very popular and there were people coming and asking to audition for dance in his company all the time. As for Nacho, he also asked for a lot from his dancers, and if you couldn’t meet his expectations there would always be someone else to take your place. There had never been enough of that kind of aggressive competition in Singapore. However, when the competition gets too tough, you begin to feel like a part in a machine, so I also began to perform with other companies. It was so that I could continue the challenge and the competition while still enjoying life and enjoying performing. It was tough in ways, but I was able to give 100% every day, so it was fulfilling.

- Then, in 2007, you returned to Singapore. Since you had been a principal in a famous company, you must have had the option of staying in Europe, didn’t you?

- Yes, I did. Spain is a country with wonderful culture and people, and I think of it as my second home, but I had learned enough in five years and I felt the need for a big change, so I decided to become a choreographer. It is true that I could have remained in Europe, but as an Asian, I wanted to do choreography that bought out Asian physicality to the fullest. Of course, that wouldn’t have been impossible to do in Europe, but the mentality and culture it is rooted in is different.

- Is there an influence of Nacho’s style in you work now?

- There probably is an influence, but the direction I am working in is different. I am interested in expression that is true to one’s own physicality as a human being, and I am searching for something more Asian in character. The company name “T.H.E.” is the acronym for The Human Expression. The dance I aim to create is dance that expresses the human body, human existence and the conditions of human life.

- When you returned to Singapore, were you accepted into the dance world there with no problems?

- Since Singapore is a multi-ethnic society, there is no resistance to new culture. But that characteristic has a good side and a bad side. While on the one hand it is a very open society and readily adopts new movements in dynamic ways, on the other hand, with the ease with which new things from the outside are accepted, there is a tendency to neglect or traditions.

The Human Expression – Founding a dance company for human expression

- In 2008, you established your T.H.E. dance company.

- Although it wasn’t a large amount, I got some [financial] support from Singapore’s National Arts Council. For the dancers, however, although we had them working six hours a day Monday to Friday, we were only able to give them a wage of SGD400 a month during the first two years. The seven dancers were freelance and had living expenses of their own, but I asked them to stick with me for two years, and they put their faith in me and stayed with the company.

Furthermore, we had to rent studio space, so I had to use my own money as well. Fortunately, in Spain, if you have worked for more than two years you get unemployment insurance payments, and in order to receive them I had to go back to Spain every three months during that period. Still, if you want to achieve something, you have to be prepared to invest everything you have in it. So, I was doing everything, from the creative side to the publicity. - Did the company go well.

- Even though there was an audience in Singapore that knew me, they didn’t know my company. At the time I established the company, we worked at a fast pace to present new productions about once every three months. It was really crazy. What’s more, if you have even one performance that isn’t of good quality, the audience won’t come back anymore, so we had to work very hard. In time we were able to establish a reputation that T.H.E. was a company that was professional and consistently delivered high-quality works, so by the third year, I was finally able to give the dancers a professional-level salary.

Currently we have eight dancers in the company. Half are from Singapore and the other half includes Malaysian, Chinese and also a Japanese dancer. Auditions are done on an open basis and there are no restrictions regarding nationality. Now we also have a second company. From three years ago, we have a residency agreement with NAC’s Goodman Arts Centre. It has provided us with a very good working environment with a specialized studio for us to use, but it is based on a 3-year contract, so we have to renew it. - It is great that you now have a second company. In Europe it is difficult now to maintain a large company, and the environment for bringing up young dancers is getting smaller.

- In Singapore, there are cases where second company dancers pay to receive lessons, but with our company it is free. Currently we have about 20 members ranging in age from 16 to 29. The lessons are divided into classes based not on age but on experience.

- Seeing as Singapore is a multi-ethnic country, do the dancers tend to have backgrounds in different ethnic dance traditions? What kind of training do you usually give them?

- I think of ballet as the basic foundation for all of us. The normal training routine consists of two days a week of ballet, one or two days of contemporary and one day of improvisation. From time to time we also allot time for creative work. My method is based primarily on contemporary dance, but I also place importance on improvisation. There are also the different traditional dance forms, Tai Chi Chuan, GAGA, contact improvisation, etc. that we draw on as well. At the same time we are constantly reconsidering the basics of breathing and movement, etc.

The spread of contemporary dance in Singapore has been remarkable, and it is now approaching the level of commercial viability. One of the fine qualities of the Singapore audience is their sensitivity to progressive changes, but in the process of becoming popularized, I also sense that the demand from the audience to see things that are entertaining and enjoyable to watch has become too strong. I believe that it is our job to continue to produce quality work that is high in artistic value. - Finally, I would like to ask you about your vision for the future.

- In fact, in 2017 there is going to be a big change in our festival format. We plan to reduce the number of performances and focus more attention on creation. Now that the base for contemporary dance has spread, I believe we have reached a point where the thrust should shift from working to popularize it to efforts to raise the quality of it. It is not easy to maintain a high level of quality while attempting to create new works, but I believe that it is necessary for the artists to have a platform where they can take on new creative challenges, so my hope is that our festival can become a place for that.

- Yes. Artists need a place where they can experiment, make mistakes and fail sometimes.

- I am thinking about a format for a festival that can become the platform for unimaginable new artistic challenges. For that reason I am planning the company and festival that have been operated together until now. The festival will be left up to the festival team and I will stop doing the curating work and focus on creation as a choreographer and artist. The company has each a point of good stability now and is maturing. I believe that the time is right for me and the company to work on establishing our own unique vocabulary and deepening our aesthetic.

- So, you feel that contemporary dance in Singapore has completed its popularization stage and has now entered a stage for striving for greater quality. We look forward to your activities from now on.