- The Playwrights’ Center (hereafter, “PWC” *1 ) is recognized as the largest resource for playwrights in the U.S. First, please talk about the genesis of the Center.

- The Playwrights Center was founded in 1971, which was the time when the regional theaters (*2) were emerging and the big theaters like the Guthrie (*3) were still in their infancy. A group of playwrights who were taking classes at the University of Minnesota thought, “We need to make a place where playwrights and their works are at the fore of the process.” That’s really the genesis of the organization. The five writers including Barbara Field and John Olive started to do readings and create small opportunities to develop plays without much money and that snowballed to become this much larger institution.

- Why was it in Minneapolis, a regional city in the Midwest, not in the metropolitan cities of the East or the West Coast that PWC was founded and developed?

- I think that because of the Guthrie which opened in 1963, there was an active and growing theater scene in Minneapolis. The Guthrie attracted top rate directors and actors, and in response, playwrights intended to create a milieu where they could get supported. Also Minnesota has always valued culture and artistic creation, and there have been always been financial resources to support it.

- Thirty seven years after the inception, what kind of programs does PWC provide today?

-

I’d like to say that there are three paths to the PWC and some off-shoots from the three paths. The first path is a laboratory, or “Lab”. This includes PlayLabs

(*4)

, which is considered to be our national face. In the laboratory, we develop somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 to 50 plays a year. That means that the 40 to 50 playwrights get an in-depth opportunity to work with actors, directors, designers, and dramaturges. In my mind, the Lab is the heart of our work. We call it our Ruth Easton Lab as we got funding in recent years from a major donor to increase the capacity of the Lab.

The second path to access PWC is through fellowships. We re-grant to playwrights and theater artists over $200,000 a year. That’s another way that we work with both emerging and established playwrights and theater artists.

The third way that one accesses the Playwrights’ Center is through what we call a general membership. We have 700 to 800 general members today and they pay an annual fee and get various information from us. They get writers’ opportunities, and they get to hear top people in the field do blogs, etc and converse on line. It’s mainly online services. That’s a way for us to keep people attached to the field of playwriting. Anyone can participate with us that way. Even someone who hasn’t written a play can become a member. For a lot of writers who are emerging or beginning it’s a way of staying inspired and knowing where to apply for grants, and staying connected to professionals talking about the field. - Please talk more in details about the Labs.

-

PWC’s Lab provides the best possible R&D (Research and Development) for the playwrights and their plays. We try in the best way we can to develop the play to get it production-ready. Collaborators bring vision to the process, but when we bring in directors, dramaturges, actors and designers to the process, our goal is to have the playwright’s voice be at the fore during the time that the play exists here.

My limited experience in working in Japan is, and this is not unusual in the U.S. as well, that theater can be a very director driven experience where the directors find their own sense about the play. However, while the play is here at PWC, it is really about development of the script and bringing excellence to that script. In the context of American theater, scripts live by themselves out in the world, not attached to the writers. The writer sends them out and theaters/producers look at them, so, we have to try to get as much excellence on the page as we can. - How do you select which plays to develop at the PlayLabs, the largest lab of the PWC?

- The history of selecting PlayLabs scripts has been that we would get may be 300 to 400 scripts, and we would whittle down that group to five to develop in the PlayLabs. Anyone can apply for a fee, and we will read a sample of your script first, then, go through the rounds: semi-finalists and finalists. The selection panel consists of directors, dramaturges, and playwrights. For PlayLabs, after long discussions with the panel, I make the ultimate decision on the line-up with a lot of input from colleagues in the field. We are in a position now because the organization has grown so much that probably PlayLabs will become a reflection of the Core Writers Program (*5) that the two programs will merge so that basically, we will develop plays of our core writers at PlayLabs.

- I understand that about 80% of the plays developed at the PlayLabs will get fully produced eventually, which I think is truly phenomenal. – For example, Jordan Harrison’s “Finn in the Underworld”, and Lee Blessing ’s “Body of Water” most recently went on to full production following development at PlayLabs.

-

Of course, we are very interested in having plays produced that come from our Lab. Obviously, the ultimate success for us is production. But first and foremost, we develop playwrights. We don’t pick a play to develop because we think that it’ll get a production. We put our faith in writers. We develop playwrights and we hope that what will emerge from that is really good plays that will get produced and that’s generally been the case.

Most theaters, however, are going, “Is this play good for the market?” and/or “Will my audience like this play?” Whereas we’re just saying, “This playwright has an exciting voice, and we want to develop the script.” And we start there. So, you’ll see that the work we do has a broad range in terms of its aesthetic diversity. It can be a kitchen sink drama, it can be very experimental, or, it can be a musical. - What I’m hearing is that all PWC programs are coming from the philosophy and based on the policy of what is the best way to support and nurture the playwrights and their talents.

-

Yes. Since its inception, we are driven by the vision of the playwrights and all PWC programs are implemented with this as the guiding principle.

Are there other organizations which may be smaller than PWC but engaged in similar kind of activities?

- There is Playwrights Foundation (*6) in San Francisco, which is quite a bit smaller, but they do a lot with their smaller budget. New Dramatist (*7) in New York is of similar size. The Lark (*8) in New York is perhaps half our size. Z-Space in San Francisco does a little bit of what we do, but they do it specifically for their region, so they are not as fully national as some of those others I named. There are a couple of other organizations that are mainly seasonal programs such as Sundance Institute, which is more of a summer development programs that does very good work. The O’Neil has been around quite a bit longer than the PWC, and there too, it’s mostly a summer series of new plays.

- Do you communicate with each other?

- Yes, and we all try to be supportive of the work of the other. In good American spirit there is a certain level of competition as we are vying for similar funds but it’s mostly very collegial.

- With your vision of connecting the American theater artists with the world theater community, PWC also works beyond the U.S. boarders. In particular, PWC took on a 3-year exchange project of playwrights with Japan (*9) since 2006. Under this project, the three Japanese playwrights, i.e. Yukiko Motoya, Masataka Matsuda and Ai Nagai and their works were introduced to the American theater community. Please share your insights on translation of theatrical scripts and describe how you actually work on the translations.

- The playwrights’ exchange project with Japan is really the first serious international exchange that the PWC has taken on. There have been some scattered exchanges with other countries over the years, but this is really the first long term commitment to international exchange and translation that we’ve made. This is the value of mine that I brought with me when I took over the PWC. I recognized that these projects take enormous amount of time, so when you (*10) approached me four, five years ago, I knew that we wouldn’t be able to do more than one country simultaneously.

When we bring Japanese playwrights under the Japan-U.S. Contemporary Plays and Playwrights Exchange Project, the actual process, in a word, is adding the Japanese playwrights, Japanese and American translators and dramaturges to the PWC’s Lab process. However, the process requires at least twice the time and work since each step of the process is conducted in both Japanese and English. First, our Japanese project partner, Saison Foundation, proposes us the candidates and their works. In order to select the scripts to develop at our Labs, we translate the playwrights’ bio and synopsis of their plays, sometimes producing a sample translation for about 10 pages of the script if necessary. We then select the Japanese and American translators and dramaturges and begin the translation. In regards to developing the translated English script, it depends on the translators, but basically, the Japanese translators take a crack at translating from Japanese into English to produce the first draft, then work closely with American co-translators to produce the second drat. After that, American dramaturges and I too will join the revisions. Of course, we ask questions of the Japanese playwrights during the process. All this needs to be done during the preparation phase. Then, we go into the “Lab” as Japanese playwrights and translators join the American team on –site in Minneapolis.

For example, in case of Yukiko Motoya and Masataka Matsuda, both playwrights participated in the exchange project as one of several playwrights in “PlayLabs” in 2006 and 2007 respectively. Thus, they both stayed in Minneapolis between 10 days to 2 weeks (PlayLabs duration varies slightly each year), like other American playwrights at PlayLabs they participated in the Lab workshops three to four hours each day for the total of 30 hours, collaborating with American directors, actors, dramaturges, and both Japanese and American translators. One or two public staged-reading(s) were held within this timeframe. During the Lab workshops, not just the translators and the playwrights, but dramaturges, actors, directors, all participants in the collaboration probe into each and every word on the script with scrutiny, sometimes experiment with paraphrasing or changing the word order. When actors find certain dialogue hard to understand or deliver, they won’t hesitate to ask questions. The American directors usually answer them, confirming the interpretations with the Japanese playwrights, or sometimes, struggle together for a while, then decide to adjust the translations. It’s quite a scene when questions and answers in both English and Japanese go back and forth in quick succession.

Ms. Ai Nagai, who was our third playwright of this project, participated in the PWC’s Director’s Series Lab, separate from PlayLabs. The basic process is the same for all Labs, but depending on the personalities of the playwrights and the collaborating “creative team,” differences emerge naturally. When we were developing Ms. Nagai’s “Women in a Holy Mess ( Katazuketai Onnnatachi ),” which unfolds through dialogues of three women in their fifties, who’ve been friends from their youth, the three American actors particularly liked the script, and were so enthusiastic about commenting on the translations, that we needed to go out of the theater where we were rehearsing to the lobby, set up a round table to specifically discuss options and edits on the translated script.

One thing I’d like to say in particular about the exchange project with Japan is that the work at both ends has been superb. The plays that have been sent to me are top quality. There are amazing writers that are coming out from Japan. These are plays that not only resonate for Japanese audiences but really have potential to resonate for an American audience. They require the time and effort and we translate them with real care and expertise.

It’s been equally labor intensive and rewarding to bring the American writers’ works to Japan and translate them into Japanese for staged-readings, yet, it’s been a different experience for me. What I feel we’re providing from this end are excellent translations that can be produced in other places. What I feel is happening in Japan is that there is a directing vision brought to the plays that opens up the minds of the American playwrights that we work with. In part, because I don’t speak Japanese, I don’t have a sense of where those plays might go after the staged reading.

Yet, this very morning, I got an e-mail from Trista Baldwin, who was in Japan last year, and Shiratama Hitsujiya, the Japanese director for her play. They are trying to do a Japanese English version, a sort of a new version of her play, “Doe,” that will be in English and Japanese to be produced. So, our exchange project created this new relationship and potentially a new play. That’s a project that I’d love to support.

The work and collaborations in the exchange project have been superb, but there have been difficulties also. What I’ve learned myself, and I’m not surprised by this, is that you can’t just do translation for the sake of doing translation. You have to commit all the way, which I think we’ve done in these projects. You have to commit to all the time and all the energy and resources for all of the collaborators to come from Japan or to come from the U.S., and to have the people from both cultures in the room all the time trying to make sense of what we don’t know about each other. Please share additional insights regarding the difference between the Japanese playwrights’ experiences in the U.S. and the American playwrights’ experiences in Japan.- When the Japanese playwrights work in the PWC Labs, since they can read English, they follow word by word and participate in the collaboration more fully as a result. Also, from the PWC perspective, because we are so used to playwrights being involved in the word by word, it fits very well into our process. Thus, I think that we are doing superior work in regards to the translation from Japanese into English than from English into Japanese. In fact, although there’s been some issue about letting the American director have some interpretive possibility in the room, the U.S.-Japan collaboration in the PWC Lab has been mostly very smooth and comfortable.

Unlike in Japan, it’s a very segregated process (for a script to go on to a full production) in the U.S. There’s a playwright who lives in one place, and there’s a director who lives in another place, and there’s a theater that exist in another place, and they all come together to make a play. It’s not like Japan, where it seems to me that the playwright and director is one person, they have a company, they produce their own work, so everything exists in the same place. My sense is that the result of it is that each company has their own aesthetic, and they’re kind of known for doing work a particular way. So, what happens when you send a play over to Japan, is that it gets pulled into that aesthetic to a certain degree, and that is both challenging and interesting and sometimes problematic to the writer. Whereas the challenges or frustration for the Japanese writer when they come here, is that they have to get over “look, I’m the writer, I’m the director and the producer.”- Please talk about the Lab’s impact on theatrical scripts. For example, “Vengeance Can Wait (original title: Boryoku to Taiki )” by Yukiko Motoya, was first develop at the PlayLabs in July 2006, then returned to Minneapolis in the fall of 2007 for the second workshop and received another public reading at the Guthrie Theater’s Dowling Studio. A playwright affiliated with Theater Mu, an Asian American theater company based in Minneapolis, attended the staged-reading, became very interested in the play and organized another public staged reading in February 2008 with the Theater Mu actors. Finally, as we talk now at the end of April 2008, “Vengeance Can Wait” is presented at PS122 in NYC as a full production. After much work in different Labs and staged readings, is “Vengeance…” a new play?

- I do think that “Vengeance Can Wait” is a new play and I love that about the translation. This is my own intellectual view point about translation, there is no such thing as word for word translation that makes any sense. I know that there are other people in the field and also other Japanese artists who would agree with me, but I think that a lot of English translation of Japanese plays has just been not good. It tried to be word for word, but then doesn’t make any sense in an American context and the result is that the work isn’t very theatrical. What we’ve done with these plays is we tried to be absolutely true to the spirit of the text, and in many cases, the word for word of the text, but we’ve also tried to create plays that are going to feel theatrical to an American audience.

I feel like that “Vengeance Can Wait” is an example of a just brilliantly translated script in that it’s true to the original, and it’s also something totally different. Even the phenomena of the brother – sister relationship in the context of “Imoto-moe” that the Vengeance is based in, that kind of social phenomena doesn’t exist here. So, because it doesn’t exist, the play itself cannot be entirely true to the script. The American creative team had to bring some other element, “Daddy” in this case, to the script. It’s taken an enormous amount of time to find the connection, but I think we had some real success in finding our way.

In every process we have learned more about how to do it better and we still struggle with some issues, for example, “Do we keep the Japanese names for performances in English?”, or “Are these plays only for Asian American actors or can a group of white actors or an ethnically mixed cast do these plays?” I don’t know that there’s a right or wrong answers to any of those questions. As Japan is a high-context (*11) culture, I think it’s about context. I think that you have to figure out what your own context is, figure out how you want to perform the play. “Vengeance…” presented at PS 122 in New York City now is with all Asian American actors, and it’s a whole different experience from PWC’s staged-reading. Yukiko told us specifically that it does not matter whether “Vengeance…” should be performed by all Asian American cast or not.- Are you considering working with other countries on a similar playwrights exchange projects in the future?

- We have two more Japanese playwrights this year and we’re going to finish the playwrights exchange project with Japan. I’d love to keep some connection – maybe we do one playwright every year, or every other year, because there are such relationship and trust among the project partners. On a selfish level, I love Japanese culture and I love the work that comes out of Japan. I’m just starting conversations with other people to look at who might be the next, where else we might go, and I’ve been very careful. We’ve been very lucky on this project. The key with these kinds of projects is that there has to be such commitments on both ends. These things would not have happened without Kyoko Yoshida and the U.S./Japan Cultural Trade Network’s work, mediating between both sides and both cultures. I’m very interested in finding a project where I have the kind of expertise that we have in this project, and that’s not easy to find. “Staged-reading” has become a popular form of theatrical presentation in Japan. Please talk about the significance of staged-reading and its distinction from full productions.

- The most important part of the staged-reading is that we don’t have actors taking the time to get off book. What happens in rehearsal and in production is that memorization becomes one of the key parts of the development and for us, we don’t care about that. We don’t want to take the time. We want to make the script the best it can be. We also want to figure out – do we need some sound elements, what are the things that we need to know how the script can have an impact. If you spend time either memorizing or doing cues, just sitting and tech-ing cues can take four days, so, for us, the staged readings is a way that taking something as far along as we can without the excess that production requires. It’s stripping away to the basics and that becomes what’s most important for our work at the PWC.

- So, you see it as one stage of the script development process?

- That’s right. If you think about it as a Research and Development, in pharmaceuticals, for example, we don’t think about what the packaging is going to look like, or how we’re going to market it. All we want to think about is how to make somebody feel better. It’s a metaphor in research in medication, but it is the same kind of thing.

- Do you think that a staged-reading can be for general audience? It’s getting to be quite popular in Japan and people like to attend readings of both new and classic works. Is it the same in the U.S.?

- I think that American theater has not sold the staged reading to its audiences. That said, in my experience of 10 years at PWC is that audiences love staged readings. One of the reasons that they love them is that what staged readings allow for is the full investment of our personal imaginations. When you don’t have the costume, when you don’t have the set, you have to sit and imagine the world of this play, and I think that the audience finds that very compelling. I think that the staged readings are very popular when people have the experience of them. People love them here. They come, we get full houses, but I don’t think that the theater in general, big producers have not recognized how audiences want to be part of that.

- I heard that there are some playwrights who actually write for the staged reading, and not so much for the full production. Is this true and if so, is it problematic at all?

- I think it’s true for American writers, because it’s so hard to get new plays produced here. It’s not like in Japan where you write it and direct it and produce it yourself. You write it, and you wait and wait and wait for someone else to produce it. Also, American theaters don’t take a lot of risk on new plays. What they do take risks on are workshops and staged readings because they’re much less costly, so that a lot of writers would say, I know that some theaters won’t read this and just produce it, I know a theater will read the script and say, “Let’s do a workshop or a staged reading”. I think that writers get used to that as a way in which their works are going to be seen, so it makes a lot of sense that they write that in mind.

- Please talk about the organizational structure.

- We have eight full time staff and four part-time staff. I’m the producing artistic director, which is the artistic and administrative head. I used to do all the budgets, contracts, and all those things when we were smaller, but now that the organization has grown, more of my energy can be focused on the art, which I enjoy the most. We now have a managing director who takes care of the financial end of things, and though I still oversee the whole organization and he and I work closely together, I trust a lot of day-to-day operation issues to him. We also have a technology communication person, we have a membership person who works with the group of 800 members, and we also have Michael Dixon, who’s a theater director and dramaturge and oversees the running of the laboratory, I have an assistant, so, it’s a mix of personnel, but we’re a very lean organization for what we do.

Also, we hire probably two to three hundred actors a year, another forty or fifty directors, about twenty dramaturges, ten or twenty designers, so, we are a major cultural employer in Minnesota. The budget, which is growing, is about US$1.1 million and about $450,000 goes directly to the artists. One of our jobs, separate from what gets created, is keep artists working, alive and fed. The federal government is not so interested in that, so, it’s more foundation funds, and the bulk of our support comes from the foundations, and our goal is to use that money to support the life and health of the artists.- PWC has a National Advisory Board besides a regular Board of Directors which consists of many playwrights. How does it function?

- The National Advisory Board is comprised of the top theater artists in the country. They primarily work to advise me. I call them about particular issues. They do more of a singular thing when we ask them. The Advisory Board members function as the ambassadors of the organization in terms of speaking highly about what we do.

- Please tell us a little about you. What was your major and how did you become the head of PWC?

- I have a PhD in program called comparatives studies in discourse and society, which is a cultural studies and comparative literature degree and my expertise is on textual analysis learning how to contextualize art –understand where artistic narratives fall in time and history and I have a dissertation that’s primarily about performance theory. So, my intention was to be an academic. Then, when I “stumbled upon” the Playwrights Center, I realized that this was one of the few places where my degree was actually quite worthwhile. I spend a lot of time doing dramaturgical work on plays with writers and really love to talk about the text and talk about their work and to think about how their work functions both structurally and thematically (This is part of what I do now on a regular basis. I don’t have a traditional theater back ground in that way, but that’s how I got here. I took a hiatus before going on to the job market to become an academic and did some grant writing here at the PWC and that was 1998, and I never left.

- In regards to the academic world, do you still teach at University?

- I don’t teach much anymore because of my schedule, but I did teach cultural studies at the University of Minnesota and other places for about 10 years.

- Have you worked for any other organizations?

- No. However, in the 1980s, I did spend some time in political activism, including anti-nuclear protests but started my PhD in 1991, and have been in either the academic world or the theater world since then. I’ve always been divided in half between wanting to be a full time political activist and wanting to be an artist. Finally for me, as much as I love political activism, the artistic soul won out. I have a Master’s Degree in Peace Studies, and most of my colleagues were all doing international relations and conflict resolutions and I was doing the things around Brecht and Hemmingway, always the artistic side of social justice issues. I find that I’m fortunate, of course, that contemporary American plays are often very political. Artists use their plays as a vehicle to talk about politics, so, I now find that a lot of my activism is promoting and getting behind these very political plays.

- The play we brought to Japan under the Exchange Project, “The Interview” (*12) is a very good example of what you just said. The play is about an American journalist who was kidnapped in Iraq. It was directed by Masataka Matsuda for a staged reading presentation in Japan in February 2008.

- Yes, I agree. Thank God for Art. We’re not all going to be able to go to Iraq and protest about the war. “The Interview” is a very tight, and a very quick and very emotionally driven play, and there’s a moment in the play that we just recognize so briefly our connection to one another. That, of course, is what the international translation does. It allows us to see the way in which we’re totally different that we have so little in common – our language is different, our way of thinking is different, our perceptions are different, and yet, we have to believe in some basic ways in which we connect. There’s a moment in that play where the Iraqi doctor and the American journalist understand that personal sense of “we share something”. We have to find that. The only way that the U.S. is ever going to get out of Iraq, and the only way that we’re going to live in more peaceful world is if we understand that. We have to find that overlap.

I think that in our translation work we do that. You and I have spent a lot of time trying to figure out, where do we overlap? How do we communicate? How do we make sense of it? But as we know, it takes so much time. American politicians don’t want to take that kind of time, and I think that the artists are all about taking that kind of time. I think that it’s such a beautiful way to work.- And the Playwrights Center is here to support that.

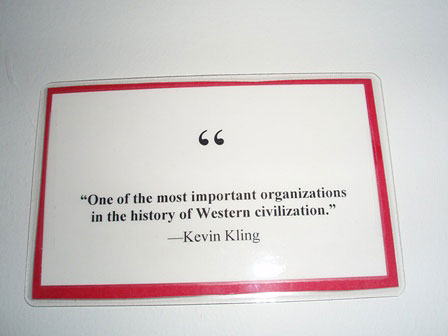

- That’s right. It’s one of the most important things we do: to give time to the artists for creation.

Polly K. Carl

The Playwrights’ Center of Minneapolis, encouraging US-Japan theater exchange as a resource supporting the development of playwrights

photo by Keri Pickett

Polly K. Carl

Producing Artistic Director, The Playwrights’ Center (PWC)

The Playwrights’ Center (PWC) in Minneapolis is recognized as the largest resource for playwrights in the U.S. Through its research and development workshops, called “Labs,” the Center develops 40 to 50 plays a year. Since 2006, the Center has also conducted a 3-year Japan-U.S. Contemporary Plays and Playwrights Exchange Project with cooperation from the Japan Cultural Trade Network (CTN) and the Saison Foundation.

https://www.pwcenter.org/

*1

The Playwrights’ Center’s facility includes a state-of-the-art 120-seat “Waring Jones Theater”, a rehearsal/meeting room, and a spacious office with a conference room and guest computers for visiting playwrights’ use.

*2

Regional theaters (also called resident theaters) in the United States are nonprofit professional theater companies that produce their own seasons. The term “regional” was used to distinguish theater companies and theater facilities with resident theater companies based outside of New York City. Regional Theaters expanded in its collective presence in the early 1960s with major funding from the Ford Foundation (1959) as well as the founding of the Guthrie Theater (1963). The term regional theater has become often used to refer to members of the League of Resident Theatres (LORT) who agree to adhere to a collective bargaining agreement with Actors’ Equity Association and other labor union for actors the theater artists.

*3

The Guthrie Theater was founded in the city of Minneapolis, MN, by Sir Tyrone Guthrie in 1963 as the first regional theater with a resident acting company that would perform the classics in rotating repertory with the highest professional standards. After four decades, the original Guthrie closed down and moved to a new location by the Mississippi River to open a new theater complex with three different stages in 2006.

*4

PlayLabs is held every July for two weeks to develop new plays through workshops and public staged readings. Playwrights, Dramaturges, Theater Directors, and Actor spend 30 hours in collaboration to develop scripts and showcase the result to theater professionals and general audience through public staged-readings. In recent years, five to eight playwrights are selected to develop their scripts. The 2008 PlayLabs will be its 26th anniversary season.

Elaine Romero working on a play at The Playwrights’ Center

Clockwise from far right:

Playwright Elaine Romero, Polly Carl, Annie Enneking, Casey Grieg, Shawn Hamilton, and dramaturg Liz Engelman.

Elaine Romero working on a play at The Playwrights’ Center

Clockwise from far right:

Playwright Elaine Romero, Polly Carl, Annie Enneking, Casey Grieg, Shawn Hamilton, and dramaturg Liz Engelman.

*5

“Core Writers” are considered as a group of leading playwrights at PWC. They are selected by a national panel, independent from PWC. “Core Writers” receive special services such as the posting of their bio and sample works on the PWC website and priority access to teaching opportunities at colleges and universities. The number of “Core Writers” in recent years varies between 30 and 40.

*6

Playwrights Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit service organization to discover and support local and national American playwrights in the inception and development of new plays.

https://www.playwrightsfoundation.org/

*7

Founded in 1949, New Dramatists is the nation’s oldest nonprofit center for the development of talented playwrights. It is a national membership organization that cultivates the work of its resident playwrights through a free, seven-year program of play readings, workshops, educational and career support.

https://www.newdramatists.org/

*8

The Lark was established in 1994to discover and develop new voices for the American theater. Initially it presented plays in full production, both new and classical works at a variety of venues in NYC. Its focus has shifted to new plays and their development. It also has active international programs.

*9

In partnership with the U.S./Japan Cultural Trade Network, Inc. (CTN), The Saison Foundation, Art Network Japan (ANJ), PWC is conducting a) “Japan-U.S. Contemporary Plays and Playwrights Project,” which receives Japanese playwrights at PWC in Minneapolis and translate their works into English for public staged-readings; and b) American Contemporary Plays and Playwrights Series, which sends American playwrights to Japan and translate their works into Japanese for public staged-readings in Japan between 2006 and 2008.

*10

Kyoko Yoshida, Director of CTN (U.S./Japan Cultural Trade Network, Inc.), who proposed the playwrights’ exchange projects with Japan to Polly Carl, is the interviewer of this article.

*11

High degree of considering the whole context in which a part exists or a word spoken.

*12

“The Interview’, by Rosanna Staffa, was translated into Japanese and presented to the public as staged-reading performances, directed by Masataka Matsuda at Kawasaki Art Center in February 2008.

PWC’s office workstation

Backstage of the Waring Jones Theater, The Playwrights’s Center

PWC内ウエアリング・ジョーンズ・シアター内の仕込み風景

There are many eye-catching signs and posters on the wall in PWC.

Polly K. Carl, Ph.D.

Related Tags