It is 5:30 in the afternoon on Tuesday. Frightened by thunder, Mizue rushes into her house. Ever since the “pika” (atomic bomb) three years ago, Mizue has been terribly frightened by thunder. Inside the house, Mizue’s father, Takezo, is worried that the steamed buns she was given by the young man Kinoshita, who is a frequent user of the library where she works, might have been crushed in her frantic rush. Kinoshita is a teaching assistant for a university physics course whose personal interest is collecting remnants from the atomic bombing that reveal its effect. These steamed dumplings are a symbol of the love Mizue feels for Kinoshita. In a monologue, Takezo reveals that he has appeared in order to encourage Mizue in this love and explains that his daughter has forbidden herself to fall in love with anyone. Gradually it is revealed that Takezo is the ghost of Mizue’s father who died in the atomic bombing.

In scene two it is past 8:00 in the evening on the following day, Wednesday. Mizue is practicing for the next day’s Storytelling Time, where she reads old folk tales to the local children. Listening nearby, Takezo expresses his doubt that today’s children will get any meaning out of the old folk tales as they are, and he suggests that it might be good if the endings could be changed. Mizue has made it her principle not to tamper with the old folk tales, and she has just had an argument with Kinoshita that day during lunch break, when he asked her if the folk tales couldn’t be used in some way to communicate to children the cruel and fearsome tragedy of the atomic bomb. That Kinoshita happens to be in danger of being kicked out of his boarding house room because it is now overflowing with remnants of the atomic bombing that he is feverishly collecting, such as roof tiles with surfaces distorted into spine-like patterns by the intense heat of the bomb and medicine bottles distorted by the heat into strange shapes. Meanwhile, Takezo tries reciting a version of the familiar Issun Boshi (One-inch Boy) and Momotaro (Peach Boy) he has modified to include a message about the atomic bombing, but he finds the result to be too gruesome for the ears of the people of Hiroshima.

In the next scene it is noon of the following day, Thursday. The Storytelling Time has been cancelled because of rain. Mizue ignores her date to meet Kinoshita at lunchtime and goes home early. There, Takezo has found a letter by Mizue telling Kinoshita that he can move some of his remnants collection to her house, but he also listens to Mizue saying that she can’t allow herself to see Kinoshita anymore. When her father asks her is the fear of the after-effects of the atomic radiation exposure is her reason, Mizue answers that Kinoshita has already promised to care for her with his life if she falls ill from radiation poisoning and to do his best to raise their children, even if they are inflicted with radiation-induced mutations. But she goes on to say that so many people with greater claim to a happy life than her died in the bombing and she can’t close her eyes to that fact and pursue her own happiness as if those people had never existed. In her eyes, death was the natural course on that day when the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and having survived was unnatural, and thus she feels ashamed to be alive.

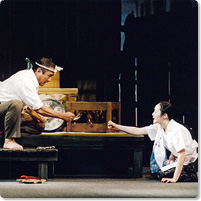

The fourth scene takes place the next day, Friday, at 6:00 in the evening. It has been decided to take in Kinoshita’s atomic holocaust remnant collection and he is making repeated trips to the house with loads of those remnants. When she sees among the collection a head of a Jizo [Buddhist saint] statue with its face melted by the atomic blast, Mizue lets out a gasp that is close to a scream of pain. She had been preparing to make a meal for Kinoshita, but when she sees the face of the Jizo again, Mizue has another change of heart and begins packing her things with the intention of leaving home so that she will never see him again. Seeing Takezo’s distress at what she is trying to do, Mizue tells her father that he is the one for whom she bears the greatest burden of shame. On that fateful day three years ago, Mizue and her father were both in the garden of their home when the bomb fell. When the house collapsed, Takezo was trapped beneath it with a burned face like that of the Jizo. But, try as she could, she was unable to free him from beneath the debris. As the flames spread, her father told her to run and save herself while she still could. When Mizue refused, he told her to run and consider it his last wish and her last act of filial piety. In this way they had reconciled themselves to a fate in which one would live and the other die, Takezo reminds her. Still, Mizue insists that a daughter who would run off and leave her father to die has no right to happiness. Then Takezo says, “I am the one who brought you into this world. You have survived in order to remember that tens of thousands of people made that kind of tragic parting that day.” Then he tells her that if she is too foolish a daughter to understand that, then she must give him someone who will understand: a grandchild or a great grandchild. Hearing these words, Mizue slowly turns and walks off to the kitchen to begin preparing a dinner for Kinoshita. We see that she has surely decided to face the happiness that awaits her and to go on living. Mizue asks her father when he will come to visit her again, and he replies that it depends on her. Mizue smiles in what seems like the first time in a long time, as she answers, “Might be a while.”