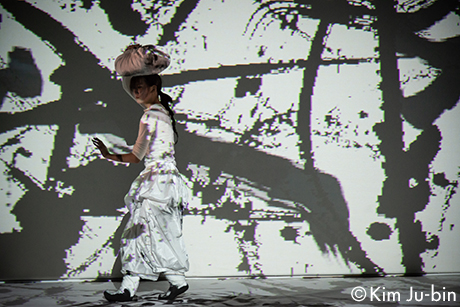

MONOTANZ SEOUL 2021

(Oct. 2021 at Seongsu Art Hall)

(C) 2021 Monotanz Seoul Kim Ju-bin

Pyo Sangman Taking care of me

Supporting the Spread of Korean Contemporary Dance Overseas

Independent Producer Sin Ae Park

Sin Ae Park is active as an international dance producer in the dynamically evolving Korean dance scene. In 2012, she switched from dancer to producer, and in 2014, she founded Korea Dance Abroad, a non-profit organization supporting dance artists overseas. An irreplaceable presence for the Korean dance world in the field of international exchange, she serves as artistic director of MONOTANZ SEOUL, as a curator for the S.O.U.M. Festival in Paris, France, and as the international manager for the Seoul International Choreographic Festival (SCF).

MONOTANZ SEOUL 2021

(Oct. 2021 at Seongsu Art Hall)

(C) 2021 Monotanz Seoul Kim Ju-bin

Pyo Sangman Taking care of me

Kim Sung-young Bottari-The trajectory of mind

Korea Dance Abroad

https://koreadanceabroad.wixsite.com/koreadanceabroad/

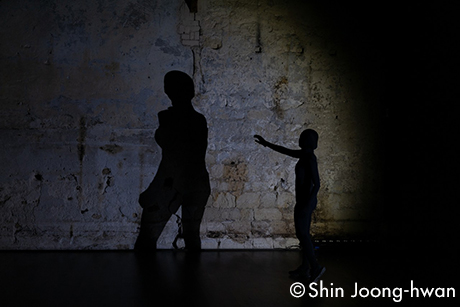

Spectacle Of Unlimited Movements (S.O.U.M.)

(C) 2022 Festival International de Danse SOUM Shin Joong-hwan

Unplugged Bodies

Dance Traveler

Related Tags