- In your student days you were an actor in small-theater plays. Would you begin by telling us about your first encounters with theater?

- When I was in middle school, I went to see a play by Juro Kara’s Red Tent company and was really stunned by the performance, and that got me interested in the Angura (underground) theater movement. I was still a middle school student, so going to this tent full of weird adults was a bit scary, but it looked so cool to me. That experience convinced me to do theater in high school, and when I went to Rikkyo University there were a number of student theater groups and I participated in performances as an actor. I was acting in about ten plays a year. You could say that my formative years were spent living the “Shimo-Kitazawa life” in that district of Tokyo where the small-theater movement theaters were concentrated, and my ultimate dream was to perform at the Honda Gekijo theater there.

Most of my performances were in the plays of Kyoji Matsumoto’s company Rumpty Pumpty. Since I was born in 1967, I was active as a stage actor from the 1980s into the first half of the 1990s. It was an era when the small-theater movement was strong and full of vitality. - When did you begin working on 2.5-D musicals?

- The shift came when I was around 25 years old. As I watched the older actors, I realized that they were continuing to act while at the same time advancing steadily in the day jobs where they worked to support themselves. It was hard to tell whether their real profession was in their day jobs or their theater acting. After thinking for a while about whether I should continue like this as an actor, I finally decided to start my production company Nelke Planning. When I started the company, it was a period when most of our production work was in performances for the [corporate or public] promotional events that were so popular at the time, and then we gradually began to get more and more production work in the theater world. At that time there were no production companies in the small-theater world, so we were getting production and general business/office work for the theater companies; and at the same time I was still involved in the actual theater performances.

As I was working in that way, I got a request to help out on the production of a musical based on a manga original. That was Seinto Seiya (Saint Seiya: Knights of the Zodiac, 1991). It was really only a fringe, outsourced-level of involvement, but it became my first encounter with 2.5-D musicals. Of course, at the time there was no name “2.5-D,” it was simply being called a “musical” or an “anime musical,” I believe. Of course, we knew it was based on a manga work, but for the production they invited a choreographer from Broadway, and it was all very interesting. Before that, I had never seen a musical performance, and I found it very fresh and inspiring.

This production became the start of [involvement in] productions of a number of anime musicals. For example, there were productions of a number of so-called girl musicals based on manga series published in girl manga magazines that later became anime movies as well, such as Himechan no Ribon (Hime-chan’s Ribbon), Akazukin Chacha (literally Red Riding Hood Chacha) and Mizuiro Jidai (Aqua age, or Blue Green Years in English), all of which were referred to as “joji mono” (musicals for elementary school girls). None of them really became big hits, but there were some good works among them. The production was done on a committee type basis with corporations from a variety fields of participating.

The first of the 2.5-D musicals to really become a hit was HUNTER×HUNTER (2000). What made this staging so revolutionary was that the voice actors who had done the dubbing for the anime movies acted out the same role on stage in the musical. For example, the popular voice actress Junko Takeuchi who had performed the voice dubbing for the story’s main character, Gon, in the anime version was now right there on stage playing the role of Gon, which attracted many of the anime’s fans to the musical and helped make it a hit. Because many voice actors were originally actors and actresses in their career, they were very easy to cast successfully in these musical roles. - Is there any particular work that made you feel that anime (manga) works were well suited to the musical medium and was a turning point for you?

- It would be Kochira Katsushika-ku Kameari Koen-mae Hashutsujo (This is the police station in front of Kameari Park in Katsushika Ward), commonly called “Kochikame” and for the musical, the script was written by LaSalle Ishii, who also directed and starred in the production (1999). It was very interesting and funny. It was turned into a downtown type musical with the characters tap dancing down the street in wooden clogs and everyone in the shopping street singing together. There were moments that brought tears and others that brought laughter; it was a warmhearted human drama like the long-running movie series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (It’s tough being a man). LaSalle-san is a comedian and TV personality but when he was a student at Waseda University he was in a musical research group. When I saw this musical, it was a real revelation for me; it made me realize that good musicals could be made in Japan too.

The musicals staged in Japan are mostly foreign works from the West like Miss Saigon, Les Miserable and Lion King. I have always had ambivalent feelings about Western works being performed by Japanese actors. But I was able to accept and be moved naturally by Kochikame. In Japan in the past, there were also completely Japanese stage works like those performed by the actor known as the “Comedy King,” Enoken (Kenichi Enomoto) a the Asakusa Opera, and musical movies like Tanuki Goten (The Badger Palace) series starring the singer/actress Hibari Misora (called Comedy Operettas). In other words, there is the DNA in the Japanese to accept and enjoy song & dance stage works. So, I felt no ambivalence at all when, in Kochikame, we had the policeman singing, or a song routine about the policeman chasing a thief. I realized this about ten years after work started on anime musicals, in around 2000. - What was the first work you produced?

- The first one done from an initial proposal of my own was the MUSICAL THE PRINCE OF TENNIS (nickname in Japan: Tenimyu) (2003). At the time there were still few 2.5-D musicals productions, and I still didn’t think of it as my main line of work, but I thought that if I was going to do one it would have to be based on that manga. At the time, both the manga and the anime were already hits.

For that production the most difficult part was the casting. All the casting was done by audition and all were cast with male actors. Also, I got a director who was also a choreographer. For the male dancers’ choreography, I remembered that the work of Yukio Ueshima was highly acclaimed and I went to ask him to work with us.

I gave Ueshima-san a book of the original The Prince of Tennis manga and said that I wanted to make this into a musical and asked him straight off if he would direct it for me. Ueshima-san told me that he had never directed a stage production, but then I told him that if he wouldn’t direct it for me, I would scrap the whole idea. He leafed through the book and said, “This is almost all about tennis matches. Do you have any directing plan?” I just answered, “No idea.” (Laughs) But he accepted the offer to direct it, and the project started from there.

Sometime later I asked Ueshima-san why he had accepted the offer and he said that when he watched characters playing tennis, it looked like they were dancing, so he thought he would be able to direct a play about tennis. Of course, I was thinking that because it was a musical there would be singing and dancing, but I had no idea of doing all of the tennis match scenes in dance. Ueshima asked me what we should do for the balls, and all I could answer was, “Yes, what shall we do?” I had even been thinking of trying to attach a ball to a pole and wave it back and forth, but in fact I had no real strategy and no idea of how to make it work.

Neither Ueshima-san nor I had any experience playing tennis. And, only one of the actors had any tennis experience. During the ensuing month and a half of work in the rehearsal studio, we went through a lot of trial and error. One good thing was that the Middle Hall of the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre where the musical would be performed had a stage lift. And, when we tried using the lift to have the actors rise as they sang swinging their rackets, it looked cool and was interesting. In the end it became a stage production that was like half concert. - What was it like at the eventual performances?

- It wasn’t a cast of actors who were generally well known, so we had planned performances for a total audience of about 5,000, but for the first day the tickets didn’t sell very well and only about half of the [834] seats in the hall were filled. But then there was a sudden “change” after the end of the first act. When the play is good, you will hear a rush of conversation between the people in the audience when intermission begins and the audience lights come on. And that is what happened! The audience went out into the lobby and, because there was no real spread of SNS in Japan at the time, many of the girls in audience were excitedly calling their friends on their cellphones. So, I had a sure sense that this was going to be a success.

Right away I decided that we would have a second set of performances. After that opening performance, we were selling tickets in the lobby for the following days’ performances and the number of reservations was growing. I sensed that this was going to be a hit like nothing I had experienced before, so I boldly went to the theater’s management and reserved a schedule of days for a second staging and we held it within the year. Until then, I had works that I had felt were successful, but in terms of a program of performances, but “Tenimyu” was No. 1. I had the feeling that this was the start of a big new wave. - What was the makeup of the audience like?

- At the time of this first show, it was the pattern for fans of the original manga to come on their own, and I believe that most of them had never been to a theater performance or a musical before. Since none of the actors were famous, there were virtually no actor fans coming. So, it means that it was the fans of the original manga that came and like the show.

However, something unexpected also happened. The audience were mostly young people who didn’t know the etiquette of watching a stage performance, and since they were really fans of the original manga characters, when the actor playing the character Tezuka would come on stage, the Tezuka fans in the audience would do things like shout, “Tezuka,” or wave placards with the name Tezuka written on it. And since “cosplay” (dressing up in the costumes of manga/anime characters) was big, there would be fans who came to the show dressed up in a costume of the character they liked. The result was that arguments broke out among the audience, with people saying that the cosplay was a distraction, or that the placards made it hard to see the stage, or that, since it’s a musical, people should stop shouting out the names of the characters when they appeared. The actors also found it hard to perform in that kind of atmosphere, so they used the Web to tell people about the basic rules and etiquette of watching a musical.

Once the rules were set—no cosplay, no calling out the names of the characters, no placards, Please watch the show quietly—then everyone obeyed the rules, because they were a good audience. But, seeing that, I couldn’t help but feel sorry for them at the same time. Since we felt that these constrictions were also unhealthy in a way, we started doing concerts by the musical’s actors—what they call gala-concerts in the musical industry. If we had stage performances in the spring and winter, we planned a concert for the autumn, where the fans could release all their pent up energy by shouting “Tezuka” or “Ryoma” and letting it all out.

However, since for the first concert we rented the Yoyogi 1st Gymnasium that holds 13,000 people, we were only able to fill about half the seats again that time. But, due to the fact that the number of performers wasn’t large, and the number of songs wasn’t sufficient, and also since the performers weren’t necessarily great singers, it is understandable (laughs). Understandably, I regretted that overestimation, and the next time we used the Pacifico Yokohama venue that holds about 4,000 people. The fans looked like they really enjoyed it and went wild waving their penlights. It felt very good to see these young people who were mostly the type that seldom left their homes coming out to jump and shout and thoroughly enjoy themselves at these concerts. - What were the criteria you used in the auditions for the casting of Tenimyu?

- In addition to a visual appearance that doesn’t violate the image of the manga character they would play, we placed importance in the casting on whether or not the actor had an essence that matched the character. Still today, the prime criteria is that the actor matches the “type” of the character they will play. If the actor doesn’t fit the fans’ image of the character, that will start a sense of incongruity that will cause ambivalence in them throughout the two hours they are watching the show.

- What are your thoughts about designing of a character?

- The first thing I am concerned about is that the audience doesn’t feel any sense of incongruity [with the original manga character]. For example, with the musical Shojo Kakumei Utena (Revolutionary Girl Utena) the lead role of Utena was played by Yu Daiki, a former Takarazuka Revue musical star who specialized in male roles. In the original manga Utena has bright pink hair and fights in a miniskirt, but we though it would be strange to have a star like Daiki-san perform with pink hair, so we kept her hair black and just put pink streaks in it. We were worried about the effect, but since we were careful to use the symbols of the original, the audience accepted it. This is an example of the methods you can use, but as a rule we try to get as close to the original manga as possible. It is best to do everything you can to get close to the original. To make the hairstyle as close to the original as possible, I have at times even counted the number of spikes in the character’s hairstyle in the manga. At first, [with the hairstyles and costumes, etc.] it was like extreme cosplay.

We thought about ways to avoid having the audience feel a sense of incongruity in everything from the costumes and wigs to the dialogue in the script. With Tenimyu, we used only words and lines that actually appeared in the original. We put those lines together to make the story. It wasn’t that the author of the original asked us to do that, it was also partly Ueshima-san’s policy, so we didn’t use words that weren’t in the original. That is why we had fans saying that they felt as if the play had come straight out of the manga. They felt as if, there on the stage, the characters Tezuka and Ryoma had come to life. That is exactly what our aim was. - Tenimyu became a big hit and then it went on to become a series.

- It was fine that it had been a hit, but there was such a rush of orders for tickets for the last performance that they had to be given out on a lottery basis. So, in that sense the popularity caused us a lot of extra work, but it was certainly a joy that I had never experienced before in my work in theater. For the first run of 15 performances, we got an audience of about 10,000. When that state continued for about two years, we eventually had to start thinking about a problem we had never expected: the growing ages of the original performers. The musical had produced some popular actors, but some were as old as 27 at the start, and if they continued to perform Tenimyu as they got older, the schoolboy context of the original would be lost.

So, as a last resort, we had to introduce the process of having the actors “graduate” from the production as they got older. But when we announced that, we got a response from the fans that included booing and angry questioning of why we were making the actors quit. When we announced the 2nd generation of Tenimyu actors, it did nothing to calm the storm of opposition. The audience questionnaires we got back were full of comments saying, “So-and-so isn’t as good as [the 1st generation actor]. Go back to the 1st-generation cast right now!” But as the performances continued, [2nd-generation actors like] Yu Shirota, Koji Seto and Hirofumi Araki have become popular and the fans have gradually come to accept them. By the time that the 3rd generation of actors was brought in, the “graduation” system had also become established and accepted.

By the way, the name “2.5-D musicals” was something that originated spontaneously among the fans. It seems that the fans had been referring to the manga/anime-based musicals that way among themselves for quite a while, but we didn’t become aware of the term until about three years ago. Until then we had been calling the anime musicals, which was a bit strange, because they originals were actually manga first. We thought “2.5-D” was a good term, so that is when we started using “2.5-D musicals” too. - When did exporting the musicals abroad begin?

- Tenimyu was first performed in South Korea and Taiwan in 2008. A lot of fans from Japan also went to see these performances, and I would say that the audiences were about half local people and half Japanese. The seats in the venues were about half full, I believe. But, the audience response was very strong, in terms of the excitement they expressed. It made us realize that these shows [and the manga originals] had many fans overseas, and that made it very enjoyable. There were boys shouting out “Tezuka” when he came on stage, and when the actors’ lines were projected on stage [as subtitles] the audience really responded with excitement. I was surprised to see how honest and appreciative the audience response was. Commercially, however, the overseas performances were seriously in the red, so we couldn’t continue the export experiment and the challenge of building audience overseas. Still, I would definitely like to try it again if the opportunity arises.

In 2013, a musical study tour group of directors, producers and stage directors came to Japan from South Korea, and they visited our company as one of the stops. Statistically, Japan’s musical market is the second largest in the world after the U.S. I believe that is because of the existence of the Takarazuka Revue Company and the Gekidan Shiki company. But, I had thought that musicals were much more popular in Korea than in Japan. Because, in the Daehangno (University Road) theater district of Seoul there are over 200 small theaters, and about 60% of them stage original musicals, and there are about five directors whose musicals have runs as long as five years.

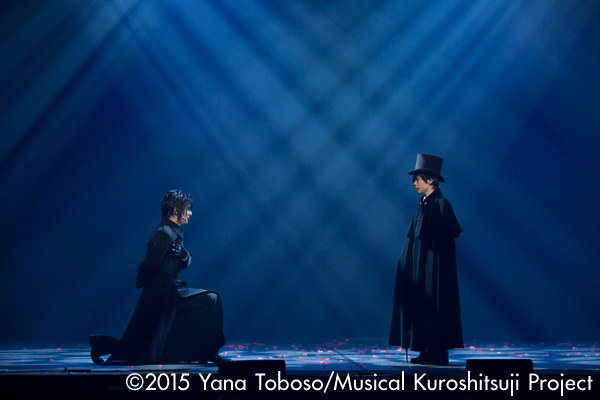

When I was asked by the members of that study tour what the best original Japanese musicals were, I had to answer that there were really no original musicals that I could seriously recommend to them. After that, the tour members went to see a number of Japanese stages, and when I saw them again at the goodbye party before the left, I was told, “Matsuda-san, why did you lie to us? Japan does have good original plays.” When I asked them what they had seen, they said the Musical Kuroshitsuji. I was so shocked felt as if I had just smacked on the head.

Although I had been working on 2.5-D musicals, since I was originally from a [non-musical] “straight theater” background, I had always thought of the 2.5-D musicals as something else. I feel embarrassed and foolish now that I had had that attitude, and it was a real revelation for me to be told by the Korean study tour members that [2.5-D musicals] were indeed true Japanese originals. They told us that Kuroshitsuji had great costumes and scenery, and the music is outstanding too. They did say, however, that the actors weren’t especially good singers (laughs). I was aware that some of the actors had weaknesses as vocalists, so I agreed with them to some degree on that point, but more than anything, their comments made me feel that I personally had to work more actively and harder to produce 2.5-D musicals. And, I also realized that these musicals were a genre that we could take abroad and compete on the world stage with.

Until recently, all of the musicals that have become big hits in Japan have been ones licensed from the West (Europe or North America). In other words, Japan has continued to work hard to produce Western musical and paying royalties to stage them. That is all fine and well, but isn’t it only natural that we should also want to make original Japanese musicals and export them abroad? Although it is difficult to export original Japanese straight plays, but seeing how popular and well-loved Japanese manga and anime are around the world, if we can succeed in turning them into good quality stages, it should be a genre that we can compete successfully with on the world stage. That is the feeling I got from that encounter with the Korean theater professionals that toured Japan. - I wonder how people overseas watch Japanese anime today?

- Now it is on the Internet. Until now, television broadcasts were the only way for people overseas to watch Japanese anime. With the spread of the Internet, anyone can now watch anime easily on sites like YouTube. There are problems like illegal uploads, and it is a big problem for the anime companies. But lately, in order to face and deal with the problems, TV stations and anime production companies have started to officially distribute their woks over the Internet, so now it seems the people overseas, especially in Asia, are able to watch anime sequels virtually in real time. People who like Japanese culture also want to hear the original Japanese, so it appears that broadcasts in Japanese with local-language subtitles are more popular with many people than dubbed foreign language versions, and there are now many young people who have learned Japanese by watching anime that way. There are also people who have gotten to like things like Japanese ramen noodles that they saw characters eating in anime. So, in this way Japanese anime is spreading worldwide.

And that is why I have become convinced that 2.5-D musicals based on manga, anime and games is a genre that will enable us to compete successfully overseas as well. - Is it with that kind of idea of exporting works that led you to establish the Japan 2.5-D Musical Association?

- Yes. The effort and cost of exporting works is just too large if you try to do it on a one-off basis work by work and company by company. It is better to create an all-Japan team, a national level association to export the productions. With that kind of association we can cross over the boundaries of production companies, TV networks and publishing companies. With that idea in mind, I went to a variety of places to consult with people.

When I did, some people said that I should do it all though my company Nelke Planning, which was in fact producing more 2.5-D musicals than anyone else at the time, and I said publicly that I was going to contribute all of the knowhow available to me. I said I would supply all of the experience, knowledge and knowhow we had accumulated until now. And, I said let’s all work together to make quality works. And that is what I am still saying.

The first person I talked to was Yoshitaka Hori, the CEO of one of Japan’s leading talent agencies, Horipro Inc. Hori-san was also thinking that it wasn’t good for Japan to continue just importing musicals from abroad, so he said, “Let’s do it.” He said that he had been wanting to become involved in 2.5-D musicals anyway. After that I went to talk with a number of people who were thinking the same way, beginning with Haruki Nakayama, head of the video and game software planning, production and sales company Marvelous Inc. that we had worked together with on Tenimyu.

The main thing when trying to export stage productions overseas is the quality of the works. But, in the field of musicals, Japan is a latecomer, so we shouldn’t worry if things don’t go well at first. The Japanese work diligently and carefully when they make things and they have the ability to bring things together in good arrangements. If we put our minds to the task, I’m sure that we will succeed. I believe that we are at a point where we should work together and pool our strengths to make good productions one after another.

To do this, the first job that the Association needs to do now to raise awareness of the genre. The first thing we need to do is to take 2.5-D musicals in Japan from a [transient] boom and establish it as a full-fledged genre in the performing arts. Even though the audience draw is growing, it is still not recognized as a mainstream entertainment genre, so our immediate job is to find ways to increase recognition of our genre. To establish 2.5-D musicals as a full-fledged entertainment genre in Japan, I want to see us working through measures such as sharing information within the Association, getting out information through our Association’s official website ( https://www.j25musical.jp/ ) and soliciting members for the “2.5 Friends” program. Also, I want us to provide support for spreading out productions overseas.

At present, one year after the Association was launched, we have a membership of 75 organizations and individuals. Among the members we have not only leading companies in Japan’s entertainment industry, including publishing companies that publish manga, broadcasting networks that broadcast anime and production companied that produce stage productions but also companies from other industries like travel agencies. And new companies our still joining our Association every month. We are also holding seminars and study groups once every two months to which we invite people from other industries to solicit new members. Since we are still an industry in our infancy, we need these study sessions.

In March of this year we opened in Shibuya the AiiA 2.5 Theatre Tokyo (824 seat) as a 2.5-D specific venue. It is Japan’s first theater specializing in 2.5-D musicals and it will be run by our Association. In a tie-up with the tourism bureau of Shibuya where the theater is located, it is also being advertised to foreign visitors. For people who don’t speak Japanese, the theater offers “subtitle glasses” for each production with up to four different languages. We have also put a site online where people overseas can purchase tickets from their own country before they come to Japan. The Association will not serve as the copyright holder for individual works, but it does hold the copyright for the “2.5-D musicals” trademark.

Since we launched the Association, we have also participated in a variety of events with the aim of increasing awareness of our 2.5-D musicals overseas. For example, in the Japan Expo 2014 in Paris, the expo had some 360,000 visitors. This is good evidence of how many people have interest in Japanese culture. At the CCG Expo in Shanghai there were 250,000 visitors, and for the Japan Friendship Festival event in Jakarta, Indonesia organized by Japanese interests, the turnout was 200,000. Many of the people who came to these events were manga and anime fans. When I get back from events like these overseas, I have the feeling that the position of manga and anime is lowest in Japan, compared to overseas. In Europe and North America, manga and anime are respected as culture, and when I show people there our leaflets from 2.5-D musicals, they look at them with wide eye and say “amazing,” but when I show the same leaflets in Japan, people are most likely to say, “You certainly are in a rare (fringe) line of business.”

For the Japan Expo in Paris, we took along the actresses and actors from Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon: The Musical (nickname in Japan: SeraMyu), and in our event space with an official capacity of about 300 people, we had 2,000 turn out. It was a great success. The fans were taking pictures, and some of them were crying when they got a chance to shake the hands of the actors. The number of overseas performances are also increasing now. For example, the production Live Spectacle NARUTO-火影忍者- toured recently to Macao, Malaysia and Singapore. The response was great at all of the performances, with some fans coming in cosplay costumes and others coming as families with their children. The demographic of the audience seemed to be broader in scope than in Japan. The NARUTO-related souvenir items sold at the events were very popular; so popular that it surprised the people who ran the theaters where the events were held. Seeing these developments, I felt that we need to think seriously about the good possibilities of expanding the market for 2.5-D musicals overseas. Because, many people are waiting to see them. - It appears that there is a new range of business opportunities there.

- It may indeed be that there is a different type of merchandizing involved, compared to other types of theater. Because the shows are based in manga and anime characters, sales of character-related items offer a big source of revenue. This is a phenomenon you don’t have with other types of theater. In cases like the Live Spectacle NARUTO-火影忍者- and SeraMyu productions, there were long lines of fans lining up to buy the character-related items at the booths where they were sold at the event venues. There are people who are fans not only of the main characters but also the supporting characters, so the items can be sold in sets covering a range of characters. Since the production committee holds the rights for the related goods for each production, there is a potential for expanded business there.

Another big factor is that special DVD packages sell well. In the case of theater, you have the live performance, so DVDs don’t sell much. But with 2.5-D musicals, fans want to see things in close-up and they want to watch the scenes again and again, so they buy the DVDs. With the stage production of Yowamushi Pedaru (Grande Road), the DVD topped Japan’s Oricon weekly hit chart, selling almost 17,000 DVDs. The songs from Tenimyu are often sung by young people in Karaoke in Japan, and they always rank near the top in terms of number of Karaoke requests.

Also, lately real-time “live viewings” of the final performance of a 2.5-D musical run are now held at movie theaters around the country. Recently these live viewings are being screened not only in Japan but abroad as well, and the total number of movie theater holding the screenings in Japan and abroad has reached 80 theaters with some productions. For the live viewings of Stage Yowamushi Pedaru alone, the audience draw was 12,000.

In other words, if you say you don’t like manga or anime today, you are likely to be thought of as a bit strange. This is true overseas as well, so the winds are definitely blowing in favor of our industry. - What are your thoughts about the creators involved in making musicals from manga, anime or games?

- Looking back on the history of the genre, I believe it was the Takarazuka Revue’s musical stage production based on the popular manga Versailles no Bara (The Rose of Versailles) in 1974 that opened up the way for 2.5-D musicals based on manga and anime. The Takarazuka Revue is an all-female performance troupe, which in itself brings an element of fantasy to the world of performance they create, so I believe that from the outset they were well suited to the 2.5-D musical genre, in which there is always a strong element of fantasy, even when the stories portray very real worlds. After that, there was a very active use of manga and anime subjects in stage productions like Black Jack, Lupin Sansei (Lupin III) and Rurouni Kenshin. In addition, although it was not a musical, Theater director Yukio Ninagawa has done a stage production based on the manga Garasu no Kamen (Glass Mask), and director Tamiya Kuriyama has staged Death Note –the Musical. Some of the most famous names in the Japanese theater world are now taking on works in the 2.5-D musical genre, and they are creating very interesting productions. But, I hope to see even more young creators who grew up with manga and anime as part of their lives doing work in this genre. For example, the scriptwriter Norihito Nakayashiki who is writing the stage script for Hyper Production Engeki “Highkyu!!” Is a writer who loves manga and anime, and he says that being given the opportunity to write this script made him feel as if he had been awarded a medal. I personally have a good amount of experience working on adaptations of manga and anime originals, and I look forward to working with young creators whose work I respect.

However, in order to establish 2.5-D musicals as a respected genre, I feel it should be open to a variety of approaches. - What kinds of works are best suited for developing for the stage?

- Bringing a manga or anime work to the stage successfully requires some kind of clear idea. I believe that when a work can be “translated” to the stage in line with such an idea, it will be successful. For example, with Tenimyu the idea was translating the tennis match action into dance and song. With Stage Yowamushi Pedaru the idea was to not use a bicycle but to just use the handlebars and leave the rest to the human “power-mime.” It is hard to express the feeling of close involvement with the characters and the places where the action happens that you get when reading a manga when transposing it onto the stage, but if when reading the manga original or watching the anime you can get an idea about a way to transpose it to the stage, I think there will be a good chance of success. I tell young producers that if they try to transpose the work to the stage just as it is, they will fail; if they can’t find a good gimmick that works in the transposition, they will lose. I believe that is the special ingredient that 2.5-D musicals need, and that is what gives it a unique and attractive flavor of its own.

- If you have any special plans or visions you see for the future, could you tell us about them?

- This is something that Horipro Inc. is already doing with Death Note The Musical, but what I want to establish is a system for licensing the rights to the contents of a stage adaptation of a manga or anime work on the international market. For example, when producers in Japan do a production of a work from Europe or North America, they pay royalties to the copyright owners when performances are held. Now I want us to be able to sell the rights for performances of our Japanese musicals overseas in the same way. The Lion King is being performed now in seven countries around the world, and every day royalties from those performances are coming in to the copyright holder, the publisher. In the same way, the Korean version of Death Note The Musical and the French version of SeraMyu and other 2.5-D musicals will be performed in various markets overseas. For example, I have an image in my head that if a production of NARUTO by Cirque du Soleil were to open in Las Vegas, there would be an incredible number of people coming to see it. If you combined the unequalled skills of Cirque du Soleil with the compelling story of the ninja character NARUTO, there is no way it is not going to be a hit.

The problem with Japanese theater is that the number of theaters is limited and the number of performance days is decided from the start, but the minute you put a system for selling the performance rights overseas in place, you have the possibility for long runs proportional to the demand. The minute you get a system like they have on Broadway or in the West End, theater will become a big business. I believe that in 2.5-D musicals we have a opportunity to change show business in Japan in a big way.

Something that I am often told by people overseas is, “You have real treasures in Japan, so why don’t we use them,” and, “Japan is a treasure chest of contents.” Even though we have lots of interesting novels and movies and manga, they all remain shut away in a box unused. Japanese manga and anime are loved by people all over the world, so we have got to do more to spread that wealth. Today, live contents are a real, vital asset all around the world, so there is no way you can lose if you connect that energy to the strength of the original manga and anime and video/computer games. The only other thing we need is intelligence and courage. Even the Japanese language barrier that has long been a complex among many Japanese is no longer a problem. Thanks to the power of manga, there are now a growing number of people around the world who are learning Japanese.

I really believe that the world of show business is going to change with the spread of the 2.5-D musicals. I think that this is a challenge we should take on with pride.

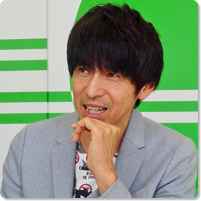

Makoto Matsuda

The vision of Makoto Matsuda

The producer behind the “2.5-D Musicals”

Makoto Matsuda

Chairman of Japan 2.5-Dimensional Musical Association, President and CEO of Nelke Planning Co.,Ltd. and theater producer. Representative works are MUSICAL THE PRINCE OF TENNIS, Exile Theatrical Company, Romeo and Juliet, L’Opera Rock Mozart, Musical Kuroshitsuji, Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon: The Musical, Live Spectacle NARUTO-火影忍者- and others.

Japan 2.5-D Musical Association

https://www.j25musical.jp

Amidst this growing trend, last year (2014) saw the forming of the Japan 2.5-D Musical Association by a nationwide team of publishing companies, broadcasters, production companies and the like with the aim of promoting 2.5-D musicals as a world-class form of entertainment. Also, March 2015 saw the opening of a new 2.5-D musical-specific theater in Tokyo’s Shibuya district named the AiiA 2.5 Theater Tokyo, adding a new dimension and even more attention for this movement. In this interview we speak with Makoto Matsuda, Chairman of Japan 2.5-Dimensional Musical Association as well as head of production company Nelke Planning and the producer of the smash hit musical The Prince of Tennis, to learn about his vision for this new entertainment medium.

Interviewer: Norio Kohyama, non-fiction writer

MUSICAL THE PRINCE OF TENNIS

©2009 TAKESHI KONOMI ©2014 NAS, THE PRINCE OF TENNIS II PROJECT

©1999 TAKESHI KONOMI/2015 MUSICAL THE PRINCE OF TENNIS PROJECT

Musical Kuroshitsuji (Black Butler)

©2015 Yana Toboso/Musical Kuroshitsuji Project

Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon: The Musical

©Naoko Takeuchi • PNP / Musical “Sailor Moon” Production Committee 2015

Live Spectacle NARUTO-火影忍者-

©Masashi Kishimoto, Scott/SHUEISHA/Live Spectacle “NARUTO” Production Committee 2015

Stage [Yowamushi Pedal]

©Wataru Watanabe (Akitashoten) 2008 / Yowamushi Pedal GR Film Partners

©Wataru Watanabe (Akitashoten) 2008 / Marvelous, TOHO, SEGA LIVE CREATION

Death Note The Musical

©Tsugumi Ohba,Takeshi Obata/shueisha

Related Tags