- Please tell us about your background and your early days before you discovered Shakespeare?

-

My father and mother met in Kusu, a country town in Oita Prefecture, Kyushu, that’s near the popular hot-spring resort of Yufuin. I was born there on July 11, 1983. Actually, my parents’ story was a bit like that of Romeo and Juliet because their families refused to agree to them getting married, so they eloped and had me. Later, though, they split up and my father went back to his rich family in Kusu while I lived with my mother in Osaka, Singapore and Takarazuka in Hyogo Prefecture, as well as other places. Even after my mother remarried, we still moved to one place after another. My mother loves literature, and when I was born she wondered whether to name me after the famous novelist Soseki (Natsume) or Ryunosuke (Akutagawa). She still writes and now she is updating her imaginative stories on her website. With such an independent-minded mother, I dreamed about becoming a famous musician and changing the world with a star band. However, as I got into band activities more and more, I did poorly at school. Also, I went to Seifū High School in Osaka, which turns out lots of top-class gymnasts, but I couldn’t adapt to its sports-minded atmosphere so I hardly ever attended. At that time I remember vaguely thinking whether I’d be better off studying mathematics, the only subject I was interested in, or whether to continue band activities, because by then I was playing my own original rock music every day, in songs that often took lines from my favorite poet, Ryuichi Tamura. Obviously, I had no chance of passing the exams for university.After graduating high school, I worked in an office for a while, but then I changed my mind and decided I wanted to go to university. As I had very little money, I just stayed in my room and studied day after day. While I was living in Takarazuka, I went back and forth between my room and the library as I prepared for the university entrance exams. Finally I got into the Human Sciences III department at Tokyo University. As I had worked so hard, I got the top marks in almost every subject in the practice exams and the entrance exams. Yet even though I continued my band activities at the university, I finally realized an important fact — that I was not good enough to be a professional musician. (Laughs) But, I also started to get bored with university life, so I tried all kinds of part-time jobs and read widely across a broad range of subjects instead of attending classes.Then one day after a class on modern French ideas I became curious to know more about the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Pierre-Félix Guattari, so I went to the university library to find their books. There, I still clearly remember the moment when I came across Shakespeare’s Macbeth. I took out the book and read it and I instantly became absorbed in the story, in which witches appeared, people went mad, and then the witches made a prediction that Birnam Wood would come to Dunsinane Hill. I was so amazed and thought what a story that was!On the way home after that I dropped into a Tsutaya video-rental shop and found a copy of Yukio Ninagawa ’s NINAGAWA Macbeth , in which cherry trees moved instead of Birnam Wood. On stage, the world of Macbeth happened inside a Buddhist altar and I was amazed by that idea. That was the starting point of my theater life.

- After that fateful day, I believe you became deeply immersed in theatre — but how did that affect your studies in English literature at that top university?

- First, I tried to see as many contemporary small-theatre performances as possible. Of course Ninagawa’s were essential, but I also loved those by another leading dramatist, Juro Kara, and his Kara-gumi theatre company. Their stages were more vulgar in those days than most are now. I often went to the New National Theatre as well, but above all I loved the German playwright Dea Loher’s Tä towierung (Tattoo), which the great Japanese dramatist Toshiki Okada directed in 2009. Besides all that, I often went to see Kabuki and opera, and it wasn’t long before I started wanting to direct a play myself. However, I knew I had almost no chance of doing that with the university’s drama circles because they had already started their activities and it was difficult to join in mid-term. Anyway, I didn’t like the atmosphere of those drama circles much, so I joined the ESS (English Study Society) instead and directed an English-language performance of Macbeth the way I wanted.

- I’ve also heard that you joined the rehearsals of some Ninagawa productions in those days. Is that so?

- Yes. I wanted to see him at work, so I applied for a position with his company and worked at Saitama Arts Theatre. I was able to see two different sets of rehearsals as he was working on two productions at the same time — a remake of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus and Hideki Noda’s contemporary play Byakuya no Walküre (Walküre in the Midnight Sun).

I had a great experience there being able to observe everything close-up for almost three months. Then one day Ninagawa turned to me and said: “You are a student at Tokyo University, aren’t you? Do you want to be a theatre director?” When I said “Yes” to both questions, he gave me three tips: First, you must graduate from university. I would suffered so much if I didn’t have a good academic background. Secondly, he said must have my own theater company to give form to my artistic vision. And finally, I should go abroad. I realized I wouldn’t be following his advice at all by continuing to attend those rehearsals, so it wasn’t long before I told him I was going to leave to follow his suggestions, and he understood and let me go. It was a very short time, but it was an unforgettable experience for me. I still thank Ninagawa a lot.- How did you come to start your own theatre company, Kakushinhan?

- After I saw the great Shakespearean actor Kotaro Yoshida in Ninagawa’s rehearsals, I went to his base, the Shakespeare Theatre in Tokyo that was founded by Norio Deguchi in 1974, and soon ended up joining the company. I was on stage there as an actor for three years. I also toured regional theaters with them and acted at the prestigious Haiyu-za Theatre in Roppongi, Tokyo. In the meantime, I was going to university to carry out my promise to Ninagawa — though it took me 10 years to graduate.

Of course, during that period I always wanted to direct Shakespeare plays, but it was difficult to take that first step to start my own company because I was really just drifting around, although sometimes I got to watch a rehearsal at the traditional Bungaku-za theater company.Then the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami struck on March 11, 2011. When I watched the horrid images on TV, I felt a real conviction that it was now time for me to take a step forward by believing in my imagination and ability and actually creating something. So I changed my life routine and started doing theater workshops three times a week in preparation for starting my own theater company. At the same time, I wrote a play based on “Hamlet,” called “Hamlet×SHIBUYA,” that we staged as Kakushinhan’s debut production in May 2012. That play has now been translated into English and will be published by the London-based Arden Shakespeare company.- How did you develop your workshops?

- I called my theater friends and ran the workshops with two or three of them helping me. One of Kakushinhan’s main members, Maimi, was among them. To be honest, I just wanted to create chances to meet people who were interested in working with us. I didn’t really know anything about theater workshops, so it was entirely a process of trial and error. For instance, sometimes we created scenes from Shakespeare plays — or maybe we’d just swim in a swimming pool together. (Laughs) I also read essays and books by Peter Brook and Simon McBurney, and about some of their experimental methods such as “devising” — a means of collective creation proposed by McBurney’s (London-based) Complicité company. Another of Kakushinhan’s main members, Yamato Kochi, then joined through a workshop we ran after our second stage production.

- Please tell me more about your original play, “Hamlet×SHIBUYA.”

- I moved the setting of “Hamlet” from Denmark to (the trendy Tokyo hub of) Shibuya, so the story developed at its big, well-known “scramble” pedestrian crossing. I got that idea when I was at that busy place one day and thought it seemed like the castle of Elsinore, where huge numbers of people came and went every day. Then I imagined that lots of dead bodies were buried underneath the crossing and there were all kinds of information floating around down there. Political speeches were sometimes given next to that crossing as well, and murders have happened there. Hence I regarded the crossing as a public space like the castle of Elsinore, and in “Hamlet×SHIBUYA” I tried to make a connection between terrorism in a big city and the story of Hamlet.

- Afterwards, you stopped writing plays and shifted to directing works by Shakespeare. Why was that?

- Kochi’s joining our company led me to do that. While I was creating works with him, I started to think that due to his great acting skills and powers of physical expression we could perform Shakespeare plays as they were, without extra dramatization. So, despite him being full of energy and in his 30s, I presented him with the challenge of acting the role of King Lear, who is an old man, when I directed that play in 2013 as my third production with Kakushinhan. Since then, I have continued to direct Shakespeare’s texts without extra dramatization.

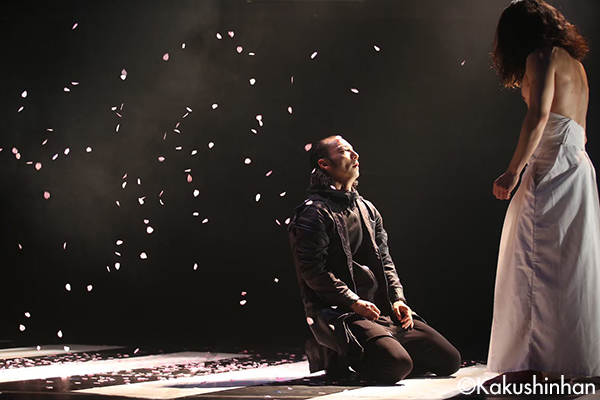

For that King Lear production I used Kazuko Matsuoka’s translation, and just cut a bit and slightly changed parts into more modern Japanese. However, above all else I always respect the power of Shakespeare’s words. For example, although he describes King Lear as being old and feeble, I thought that through the magic of theater it was very interesting to have such a well-trained and muscular actor as Kochi playing him on stage.- In 2016, in Kakushinhan’s fifth year, the company presented one of its best-known works, “The Wars of the Roses – Tetralogy,” in which Henry VI , Parts I, II and III and Richard III were staged as a consecutive series. The month-long run of that program was re-run in 2019, again drawing high praise from audiences and critics for its energetic and contemporary direction incorporating pop culture elements.

- From the beginning, Kakushinhan’s mission was to stage Shakespeare plays in ways nobody had seen before. I wanted to blend those works and my imagination from my everyday life in Tokyo. I was confident I could create original interpretations by introducing elements of my generation’s consumption culture to the classic plays. Actually, I think it’s boring to perform Shakespeare plays and just focus on the recitation of the lines, as many Japanese companies used to do. So, I’m always thinking about how to make Shakespeare contemporary.

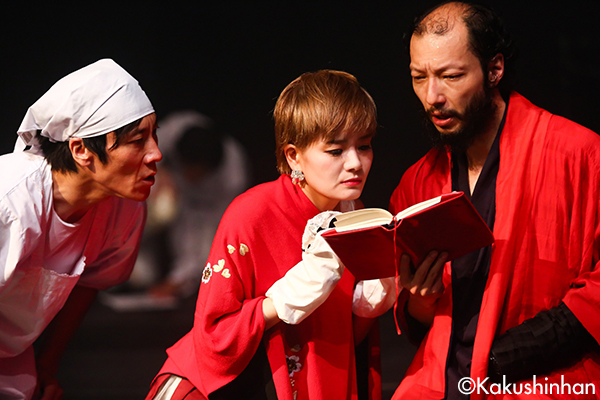

When I’m striving to convey some universal meaning, I may consider whether to connect with Shakespeare’s world through the sky or from under the ground. Through the sky, in my direction I will emphasize visual and stage effects by using lots of video images, for example. However, if I’m coming at it from under the ground, I’ll examine the actual content and words of the play. So then I’ll carefully read it through and delve into its Freudian subconscious, so to speak — just like the metaphor of a well in Haruki Murakami’s novels — as I try to connect its essence with the world of people’s deep senses and feelings. Certainly, I need to use both approaches when I direct Shakespeare plays.Nonetheless, there is still a language barrier. For instance, in any plays I direct I may opt to have some lines delivered in rap tempo to emphasize the melodious character of the rhymes — but it’s not so simple with Shakespeare because factors such as breathing are often important, and primarily I need to consider the story as a whole.Through directing different Shakespeare plays, I’ve begun to realize several points about that process.So in the reruns of Henry VI and Richard III in 2019, I used various props from our consumer lifestyle and focused on the actors’ movements and Shakespeare’s words to make the story move along spontaneously. For instance, I dressed the actors in fashionable sportswear in Henry VI because I thought familiar modern clothes would make the connection clearer between our world and the medieval one of the plays. That way, once the audiences felt close to the things on stage, they were freed to think more about the story and could enjoy the English historical drama much more.Similarly, for the soldiers’ swords in my Macbeth I used steel folding chairs. I thought it was more interesting to use familiar things like that rather than replica props.In that sense, if the actor is brilliant and uses his or her imagination well, we can use almost anything for creative props. So, if an actor picks up a sweet from a table and declares that it’s a crown, if they are good the audiences would see it as a crown. Hence, if I have great actors for a production, I can create fully imaginative theater — and that made me realize how important it is to help good actors become great actors. It’s a very simple thing, but it is actually very important to have high-quality actors with a profound knowledge of Shakespeare, Chekhov, Greek tragedy, Zeami or whatever, and who are also able to discuss these subjects and express them well in performance.- You have run your Kakushinhan Studio theater training institute since 2018. What is your purpose with that?

- After having brought on several young actors we’d hired, I began to think it was time to develop a regular training method. So then I started the institute. It’s a one-year course of three hours a day, three days a week. At the end they do graduation performances for which they normally rehearse almost every day for several weeks. We now are in our second class of students, which includes some returning graduates. If any students are good enough, we will cast them in our main productions.

In the course, I do acting training and give theater lessons using Shakespeare texts, and I also teach breathing techniques. Kochi and Maimi sometimes take charge of the acting lessons, and we’ve also invited along opera singers, swordplay instructors, Noh performers and the translator Kazuko Matsuoka as special guest lecturers.For the workshop we use our own original exercise method based on Noguchi-taiso (Noguchi-style exercises), and I insist that participants read Fūshikaden (Style and the Flower) — the famous treatise on Noh theater written in the middle ages by Zeami, the renowned aesthetician, actor and playwright.Then, for the 2019 students’ interim performance, I chose Haiyu ni tsuite no Gyakusetsu (Paradox of the Actor) by one of the leading Showa Era playwrights, Ken Miyamoto. Then they did Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar for their graduation performance in February.I picked that play because I wanted each of them to act their roles as Roman citizens in their own way after completing our training course which aims to nurture professional actors who are aware of politics and economics in the society around them, and know about their culture.They must also realize that the characters in the play are making many decisive statements, so they need to have firm voices and carefully study Mark Antony’s and Brutus’ speeches in particular.On top of that theory, because Shakespeare’s words are a form of poetry, I consistently teach them how to deliver a line in one breath when it’s necessary, and how to convey the multiple meanings in many of the lines.I also urge them to speak their lines in a natural, colloquial way — not in a “post-dramatic” artificial accent. For example, sometimes actors stress a postpositional word intentionally for dramatic effect, but that’s not a natural way of speaking. So I warn the students not to do that.By the way, Kakushinhan normally does two or three public performances a year with the full members of the company, and small-scale studio performances by trainees twice a year. Additionally, we also do three or four “pocket” performances that are handy to perform in a wide range of settings or circumstances. So, for example, I made a pocket version of Romeo and Juliet that runs for one hour with just three male actors.- How do you actually create your works? Do you have a special method?

- Fundamentally, I ask the actors to memorize all the words of a Shakespeare play to begin with — then I cut out some lines. I also start rehearsals before the casting is fixed because I think it’s nonsense if an actor only memorizes one character’s role. Shakespeare’s plays are like a chain of interlocking poems, so the actors need to swallow the author’s great wave of words and dive into his brain.

This is not the same as performing contemporary plays, in which actors usually just act their roles and only memorize their own lines. So, I often tell the actors that we are playing music like members of an orchestra, and though each of them is an instrument such as a violin or flute, they need to memorize the whole score in order to play their part well. On top of that, I encourage them to explore the dynamism of each actor’s dialogues and enjoy playing live together on stage.- Do you have your own theory on how to cut and change Shakespeare’s scripts?

- The American writer William Faulkner (1897–1962) set most of his novels and short stories in Yoknapatawpha County, a fictional place in the Deep South state of Mississippi. I follow his lead by imagining that the Bard’s stories happen in somewhere I call Shakespeare Tokyo, and I do any cutting and changing of the words on that basis. Then, I do casting and think about my direction while I am watching the rehearsals, as we try to arrive at a point where each actor’s own life experience melds with Shakespeare’s world.

In the end, I just want to create a Shakespeare Tokyo work on stage, and that is neither pure Shakespeare nor a contemporary play set in Tokyo. So, Shakespeare plays by Kakushinhan are stories that happen in that fictional Shakespeare Tokyo world.The best example would be “Hamlet×SHIBUYA,” which is set at the big so-called scramble crossing in Shibuya. We Tokyoites have become de-individualized, like tubular chairs, which is why I use them a lot in that play as metaphors of today’s consumption culture. I also change their arrangement in big groups to represent different situations.In addition, I add topical news references to the Hamlet story to link with today’s world in which so many people are using the crossing day after day without thinking about our ancestors or the voices of dead people buried below.The character in Hamlet who most ignores such deeper feelings is Claudius, the King of Denmark, whereas Hamlet himself listens to voices from the past as part of his life.Actually, I think I can detect a similarity between the culprit in the June 2008 Akihabara killing of seven people and Hamlet, who was killed by a poisoned sword as Claudius had planned. I imagine the killer’s truck that he drove into a crowd there was like his Trojan Horse, so I don’t think things have changed very much since the time of Shakespeare.Anyhow, in my approach to that classic play I started by asking: “Who is Hamlet really?”I saw him as a person who was cut off from society, and that led me to creating “Hamlet×SHIBUYA.” So I didn’t regard the play as a story that happened a long time ago in the foreign country of Denmark, but as one that is a Shakespeare Tokyo story.- Do you have other aims in your Shakespeare Tokyo plays?

- I think music and sound effects are very important. If I use a Gustav Mahler symphony or, for example, a J-pop song by Mr. Children, the impression they create will be entirely different. Music can carry important information in Shakespeare productions, so I decide on all that. I choose the songs and music and when to use them, and also whether to have live or recorded drums or shamisen or anything.

Besides the music, I normally explain my concept for the stage to our designer, Masahiro Norimine, and ask him to make the sets based on that concept. My biggest concern is how to bring together the best costumes, sets and props with our small budget. If I had a large-scale set, moving it would be a problem, so I tend to use quite simple ones, or almost empty stages.As a result, on a simple unchanging set it’s crucial how I use my imagination in choosing such props as swords and crowns, etc. An empty stage is the same idea as a Noh stage. It is suitable for almost any situation, whether it’s an imagined landscape or a particular room.Also, I make it a rule not to create a realistic set. So, if I need a Roman shrine or a Western castle I use something readily available in our daily lives to represent them. In that way, I can make a bridge between Shakespeare and Tokyo.For example, if I need a bottle of poison I don’t make a replica; I’ll give the actor a bottle of lemon soda to use instead. That means they have to use their imagination and expressive skills, which tests their powers of make-believe. In addition, if I use real everyday items for such props, then the audiences have to use their imagination, too, to see something they’re used to in a fresh new way. As I don’t have much of a budget for my productions yet, I figure out how I can turn different kinds of consumer goods into lots of different props. But, that can lead to some interesting effects, and I enjoy using my imagination. But of course, if I’m directing at bigger theaters in the future, I might change this approach.- Please tell us about your use of visual images and videos, which you do quite a lot.

- I use them because they’re simply very handy. Also, younger audiences will feel more comfortable with Shakespeare’s world if I use them a lot, because in their world people are gazing at screens and smartphones all the time. But, please remember that my priorities on stage are to show the actors and present the stories of Shakespeare’s plays — so I don’t want visual effects to obstruct or dominate the audiences’ imagination. I rank visual effects on a par with other technical effects such as lighting and sound. I believe — as the English theater titan Peter Brook said — that the most important things in theatre are the actors’ bodies, space, the text and the audiences. From the outset, at the root we need those elements — then we can think about other effects like video, lighting and sound.

- What do you require most from your actors?

- Ideally, when they play Shakespeare I look for them to speak the lines like colloquial conversations. Unless they can speak the lines without faltering, they can’t really understand the play or realistically portray the characters. If they deliver their lines unnaturally, their performance will lose its reality. That’s why I always press the actors to memorize all the lines. To gain a deep understanding of Shakespeare’s works they must be ready for that difficult challenge.

- I’ve heard that you are interested in performing outside Japan. What plans do you have in that regard?

- I want to improve my made-in-Japan Shakespeare Tokyo concept more and more and perform abroad in the future. In addition, I would like to collaborate with foreign actors to stage Shakespeare works, and also work with foreign dramatists who are Shakespeare experts. However, I don’t have any actual plans to take any plays overseas yet, but my “Hamlet×SHIBUYA” has been translated into English and will be published by the Arden Shakespeare company.

Apart from Shakespeare, I am very interested in Noh at the moment and I’m planning to do a collaboration with Tsunao Yamai from the Komparu school of Noh. In August 2020, I will direct the Japan premiere of Canadian playwright Michel Marc Bouchard’s Tom at the Farm from 2011, and I am thinking about doing it in some kind of Noh style. Before that, in May, Kakushinhan will perform A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Kinokuniya Southern Theater in Shinjuku, Tokyo. With almost 500 seats it’s bigger than our normal venues, so I’m now thinking about how to do it well there. Then after that, I want to venture out to places like New York and Berlin in 2021.I believe if I stage that part of our common cultural heritage such as Shakespeare and Greek tragedy in a contemporary context, then the vitality of theater will reach out and influence a wider range of people. Individualistic, personal expression is rampant in today’s society, but at Kakushinhan we aim to share people’s common understanding through our Shakespeare stages.But finally, I do want to say that Kakushinhan isn’t just about performing Shakespeare. We want to move ever onward and we are striving to create theater that will still be around in 400 years — like Shakespeare.

11th production

Titus Andronicus

(Aug. 14 – 20, 2017 at Kichijoji Theatre)

KAKUSHINHAN Special Reading Session “HAMLET×SHIBUYA

–FAITH, has our revenge been corrupted–”

(May. 22 – 26, 2019 at Gallery LE DECO 4)

12th production

Hamlet

(Apr. 14 – 22, 2018 at Ikebukuro Theater Green – BIG TREE THEATER)

13th production “WARS OF THE ROSES”

(Jul 25 – Aug. 12, 2019 Theater Fuushikaden)Related Tags

Ryunosuke Kimura

Ryunosuke Kimura’s new approach

Envisioning a fictional city, Shakespeare Tokyo

Ryunosuke Kimura

Director, Writer

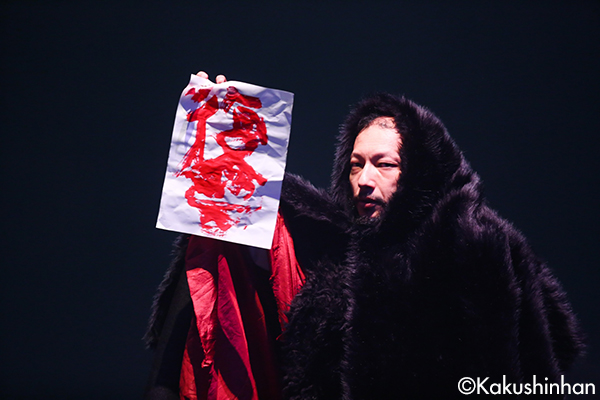

Ryunosuke Kimura’s groundbreaking Kakushinhan (Convinced Criminals) theater company first found fame with its stagings of consecutive Shakespeare plays, especially “The Wars of the Roses – Tetralogy.” Comprising the Henry VI trilogy and Richard III , the plays were staged over a month-long run at the small Theatre Fushikaden in Tokyo in 2016, with the program changing from day to day.

News of that exciting project rapidly spread by word of mouth, immediately bringing Kakushinhan to the attention of drama lovers across Japan, as audiences flocked to see its energetic young actors perform on sets in which Kimura incorporated familiar products and pop culture references as part of his direction. And although these were a new and youthful takes on Shakespeare, they won support among a broad range of theatergoers of all ages.

Interviewer: Nobuko Tanaka