- You were born in Lima, Peru in 1982. We hear that after about half a year in Peru you were brought to Japan. You wrote the stage script for your Kishida Drama Award-winning play The Story of Descending the Long Slopes of Valparaiso (Premiered 2017, hereafter Valparaiso*1) based on episodes that you actually experienced or heard of in your travels in South America, Okinawa, Ogasawara Australia and other places. It seems that your upbringing has a big influence on this recent style we see in your writing. Would you begin by telling us your thoughts on this?

-

If I begin by explaining why I was born in Peru, it begins 99 years ago when my great-grandfather emigrated from Okinawa to Peru. He later sent for my great-grandmother to join him there in Peru, and that is where my grandfather was born as a 2nd-generation Japanese-Peruvian. In 1940, at the age of 12, my grandfather returned alone to the family home in Ogimi Village, Okinawa, and there in Okinawa he attended what is today middle school to receive his education in Japanese. He lived out the War there in Okinawa and soon married my grandmother. It is said that he worked in the immigration bureau of the then U.S.-occupied Okinawa. I don’t know whether he was able to speak the Okinawa dialect Uchinaaguchi or not, but I know he spoke Spanish and Japanese. My father was born in 1950, and later his younger brother was born, and then in 1957 the family moved to Peru again.

My father grew up that way in Peru, but when he reached college age he got a Japanese Ministry of Education scholarship to study at Hokkaido University. It was there that he met my mother when she happened to visit the Foreign Students Building. After graduation, my father returned to Peru and found work, but he returned to Japan later to marry my mother and bring her back to Peru, where I was born. With all this coming and going between Peru and Okinawa, it is hard for most people to grasp our family situation when I try to explain it (laughs). They begin by asking things like, “In Peru, do they speak Peruvian?” I guess the sense of distance is also hard to know. But, well, for me it is OK if they think of it as going back and forth between Tokyo and Osaka. - Although there is a big difference in terms of distance, you were born in Peru but you were raised in Japan.

- About half a year after I was born, just my mother and I were moved to Hokkaido, and my father joined us about a year later. Kawasaki was a town with a community of Japanese-Peruvians who had come to Japan as itinerant workers, but I went all through elementary and middle school without knowing that. My father was often off somewhere working and not at home, and he would sometimes visit South America and bring back souvenirs, but I never had any special awareness of Peru other than that. From 4th grade to 6th grade of elementary school I was in Paraguay because of my father’s work, but I went to a Japanese school there. So I had almost no contact with the local children, but we lived in a big house such as we couldn’t even imagine in Japan and I had fun playing with my friends and eating delicious meat and chiorizo sausage. So I had only good images of South America. So for a long time I had the feeling that I wanted to live in South American again, but although I had some knowledge about the Japanese-descent immigrants, I never thought about things like what it meant to be an immigrant.

- What made you decide you wanted to do theater?

-

When I was in high school, I studied for one year in the U.S. and, I didn’t really know why but I thought I wanted to become an artist, because they seemed cool and popular with the girls (laughs). I thought I wanted to go to Boston Art School but the tuition was too expensive, so I gave up on that idea. Whether it by a policeman or a fire fighter, a writer and band man, regardless of the context, I wanted to be anything that thought looked cool. But, from the time I was in Paraguay, I thought in a vague way that I was not a person who belonged in a small, congested place like Japan. That is why I went to study in the U.S., since Boston Art School was beyond means, I changed direction and decided to aim at a Japanese art college.

But here in Japan art school tuition was also high. So I thought that philosophy was also cool, and since Chuo University was near my home, I went to the open-campus event, and when I did I saw that the campus there was big and looked cool. But I had no motivation or drive to study and was just doing nothing when my mother suggested Waseda University to me. It doesn’t exist anymore but at the time there was a night course called the Second Literature Department that looked interesting, and when I went for an observation opportunity, it looked cool because everyone was so intense and motivated! (Laughs) I took the entrance exam for the First and Second Literature Department and it turned out that I took the suggestion of the people around and chose the First Literature Department, and that is where I became involved in theater. - While you were at university you formed the theater company Okazaki Art Theatre (*2) in 2003. What kind of theater were you making at university? From 2015, you were writing works that connect to Valparaiso, including +51 Aviación, San Borja (thereafter just Aviacion) and ISLA! ISLA! ISLA! (after 2016 just ISLA!), but the works you were creating before that were quite different in how they were composed and the content.

-

Looking back, it was soon after my first real encounter with theater in my first year at university that I began writing scripts by myself. The first one was a story about the homeless living under the train platform at Takadanobaba Station. By the time I was in university, I became interested in the kind of political and social issues that young people in their teens tended to avoid. But, watching the Tokyo small-theater world at the time and seeing how things about people in their twenties were popular, I decided that it was perhaps best to separate politics and theater. So, when I formed the Okazaki Art Theatre as my working base, I was doing plays in a style similar to Gotanda-dan, partly because it seemed to require less money as well.

In 2004, one of my upperclassmen said he was going to enter the Toga Directors Contest (*3), and I thought that if it meant performing at Toga, I wanted to enter to. It was then that I encountered the Tadashi Suzuki and the Suzuki Training Method, and I became absorbed in that for a while. Then, for my next play I did Toshiki Okada ’s Five Days in March . When I tried directing that I liked its “noisy” style, and I thought it would be easy to write in that style, so I copied it. After that, I had the opportunity to participate in Festival/Tokyo, and at that time a read a play by Elfriede Jelinek and it made me think that it could be OK to write in such a bold style as hers. It was under that influence that I wrote black coffee (not for drinkers).

So from the beginning, I was always imitating someone else. That’s why, as strange as it may sound, I am very embarrassed to read the plays I wrote before Aviacion. In other words, although there are some places that can definitely be improved when I look back at my works since Aviacion, I believe it was from that play that I was finally working in my own style. - What was this “working style of your own” that you finally arrived at with your play Aviacion?

- I believe you could call it a style that includes my own experiences. You could say it is made up of words that have flesh, words that have bone. Looking back, I would say that the things that I wrote up through black coffee (not for drinkers) were based on things that I found in searches on the Internet, and they didn’t have much physical experience behind them. In contrast, I feel that the works from Aviacion on at least have something like physical (personal) experience behind them. Rather than just writing, “This is what I feel (what I have come to think),” having been through the experience (physically) I am able to write, “This is what happened,” and I think that gives the words a more detailed feeling of what the experience exists as inside me. After that it is a matter of getting the relativization right. And I feel that this makes it easier to work with a degree of personal detachment (distance).

- So, you are saying that because you have experienced something you can also find objective distance from it?

- Yes, that’s right. If you don’t have actual experience of something, there is a tendency, contrarily, for your personal and feelings and the ideas you want to express to come to the forefront. Because, with things you have researched but not experienced personally you are able to use them as you wish, but with things you have physical experience of, it is difficult to manipulate its actualities or interject words that weren’t actually spoken.

- Were there any other turning points in your career prior to Aviacion?

-

Around the age of 26 or 27, I attended our middle school class reunion. It was five or six years after we had all entered the working world, and all of my classmates had begun to establish their places in society. Seeing that made me think, “What have I been doing with myself?” (laughs). Shouldn’t I be doing something bit more useful to society? And from around 2010, I was thinking about bringing politics closer into my theater a bit more. Then the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami and the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Accident happened, and like everyone else I was shocked by these disasters and confused about what I should do. I felt a new sense of responsibility toward society.

Until then, I had simply felt that Tokyo was the most wonderful place, but I then realized the simple truth that I didn’t know much about anyplace else. Then I decided to go to Kumamoto with the help of Kyohei Sakaguchi (*4). After that I was recommended for a Saison Foundation overseas exchange program for young artists in 2012 that enabled me to enter the Berlin Biennale and the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels, and I also visited Morocco. It was my first time overseas in five years, and making the trip alone really scared me. When I arrived at the Berlin airport I felt that I had to call a Japanese friend of mine living there to come pick me up. But, once I got there, I felt it was both difficult and fascinating.

In 2012, I had a performance of my play Hemispherical Red and Black in Taiwan, and after that in Seoul and Beijing. Also because I hadn’t been to Okinawa since I was in middle school, I flew to its capital, Naha after our Kagoshima performance of black coffee (not for drinkers). At that time, I had little awareness of the fact that my name Kamisato is a common family name native to Okinawa. That is how little interest I had in my own roots. I hadn’t really gone there in search of my roots, but when I was in Europe I realized that I hadn’t been to places where my family roots lay, and for not much other reason than that, I decided to go to Peru too. - Then, you went to South America in 2014.

- I went to Peru and also to Argentina and Brazil. I used the grant I had received as part of my Saison Foundation Fellowship. My plan was not to do research for a new work but to just go there and assume that a work would follow from the experience. My latest three works have all taken shape in that way. I always have the intention to write memos about my discoveries neatly from the first page of a notebook, but I find that to be a bother, and I also don’t take many photographs.

- So, do you put together your works based on memories? We hear that you call your works “theater of hearsay.”

-

Yes, you could say it is just from memories. There may be things that remain like pamphlets I picked up when I visited someplace, but if you think about it, those are memories too. That is why you can say that, afterwards, I put the name “theater of hearsay” to it.

There is something that led to my realization that I was working from hearsay. It was when I read Jorge Luis Borges’ collection of essays Brodie’s Report. In 2016, I got the opportunity to study in Argentina on an overseas study program grant from the bureau of Cultural Affairs. And when that was decided a minister at the Argentinian Embassy was very pleased with that and he gave me a copy of Brodie’s Report to read. In it Borges wrote down directly in that collection stories he had heard about things like life in the thriving city of Buenos Aires in the first half of the 20th century, and from those stories it was easy to imagine scenes of the city at the time and to imagine what kinds of people lived there. It was very interesting to read because the accounts were written in a way that sounded as if some of the details had probably been changed since. And as I identified with it so thoroughly that I realized the things I had been writing in my stage notes since Aviacion had in fact been hearsay. So, when I wrote Valparaiso I concentrated on writing like that while referring to Borges’ essays. - I didn’t know that your concept of “hearsay” came from Borges.

- It was a big discovery for me. But looking back I realize that long before that I remember being told that things like letters and messengers were very important, and that had been convincing to me. I believe it was something that was already in me. Eventually, what I have been doing for the last few years has been going to the places I want to go, listening to interesting stories and then “reporting” on them. In other words that is hearsay, and since Borges’ essays had been so interesting to read, I was excited with confidence to realize that it was OK to write that way. In everyday conversations it is common to hear people say they had traveled somewhere and, “I heard this story from a strange guy, and I don’t remember very well but he said …,” And I think that is what I am doing in my plays.

- With hearsay there could be lies in it or it could be told in exaggeration.

- In the end that is always possible in hearsay and in reports. And in theater especially, it is not unusual at all for contents that are communicated to change depending on who is saying the lines and how they are said. The listener can change the interpretation of the words as they wish. So I think we cannot expect that kind of accuracy or truth to begin with.

- In the last few years you have traveled to Japanese immigrant communities in Okinawa and Ogasawara and in South America, and through the people you meet there, it seems that you are searching for boundaries between Japanese and Japanese immigrants and what decides being on the inside or the outside. For example, in Valparaiso, you depict the lives of people of American descent who have lived on Chichijima (in Ogasawara archipelago) since before Japan claimed it, and the episode you tell of the man named Lance who runs a bar there left a particularly strong impression on me. Has this been your intention?

- It has been, I believe, but as for why, I would have to admit that I personally have a deep-rooted sense of what you might call a discriminatory attitude. That is not my ideal, but it is a tendency that I can’t completely rid myself of, and ironically that may be why I continue to pursue the issue.

- So you feel that you are making these journeys in search of other realities to soften your own sense of discriminatory attitudes, do you?

-

So, in the end, I guess it is for my own purposes. I have a complex regarding language, and when I am in Europe or South America I take pride in not being seen as Japanese, but when I am in foreign countries I also tend to do things like arguing in support of Japan. I don’t know what I want to do about these contradictions or even if I want do something about them or not, and that, conversely, might be why this interest continues. If I were to say something about this, I would admit that I do use distinctions such a “Japanese” or “foreigner” or “immigrant,” but thinking on the individual level, we are really all different people. For example, Lance-san and Jenny-san in Ogasawara are both American descendants, but they are individuals who have different opinions about things that I saw at times lead to verbal exchanges that you couldn’t really call arguments and fights.

In short, rather than looking at “immigrants” from the outside, in fact, each location has its own central events happening. When you look at what those central occurrences are, they can’t be bound to words like immigrants. You may think of South American immigrants as a certain type of people, but when you actually meet with them and talk around a few beers with them, the men will likely be talking about girls, and that becomes the center of conversation. In the end, you could say that people are people, and they exist within their circle with a radius of about two meters. In the final analysis, I think that what I am interested in is what those people are talking about. The contents will be different depending on the environment. If you look at the background of the environment you will find historical factors. When you look at things from that basic standpoint there are likely to hear interesting things.

Eventually, the central events are unique to their locations and environments, so what I want to do is meet and talk with people and build some sort of personal relationship. If you do that, then you are at the center too, you’re not looking in from the margins. It may be that what I am doing now is simply increasing those types of experiences within myself. I believe what I can do is to increase the number of people who look at things from the inside, not the outside in the margins. - The idea of increasing the number of people who look at things from the inside with your activities is indeed an interesting one.

-

Wherever I go, I want to increase the number of places where we can do that kind of local conversation. I think that is the most important thing, to be able to talk with local people about what they want to talk about. What I want most is to get them to think of me as part of their local community so that I can begin by having them teach me things and then eventually I can begin to interject statements of my own values so that I can begin to get people interested in talking with me at various localities. Seen from a different angle, since my works can only come from the everyday, I am also interested in seeing how I can broaden the range of this kind of local talk.

Because I don’t want to be treated like a tourist or be guided around excessively as a guest. If I take about two weeks I can get to a feeling of the daily local life, including the moments of boredom. Of course I don’t think of it as the real daily life with just two weeks, but I do get used to the local life to some degree, and I will go to the local bar and they will say, “So, you’re here again.” That’s the kind of feeling I’m after. But, now I’m beginning to ask myself if the act of traveling to places and move around like that is enough. - We would like to ask you about your work process when you are creating works based on those types of experiences you seek. Is there some particular method you have when you are writing?

- I just start out and write something, and if the next day I feel that it isn’t what I am after, I start again. When I finally get something that makes me feel, “This is it,” to a certain degree, then I can begin to write from there. That is how it goes, I guess. There are many cases when the actors are already selected before I write the script. I choose them, but I don’t choose a person with a particular script in mind.

- Valparaiso seems to be composed mainly of monologues, but although it is hard to recognize because of the length of the lines, it appears that it is actually a case of the characters talking to someone specific. And that impression was even clearer when I watched the 2019 restaging of Valparaiso in Tokyo.

-

It is the result of my effort to write a conversational play because of the strong image of monologue as a convention of traditional theater that felt bothersome to me. But, it turned out the lines of the individual characters were still quite long, didn’t it (laughs)? Although it is rather difficult to understand due to the fact that the first scene is one of the other characters talking to the wife of the deceased who refuses to talk in her state of mourning, the play was basically an attempt by me to make a play completely one of conversation.

- Because the setting of Valparaiso is a situation where the characters are facing the mother who refuses to leave the car, the actors are facing one direction. This gives the scene something of a ceremonial aspect, something that might be likened to a Noh play or a funeral ceremony where the relatives and friends are all gathered facing the grave of the deceased. I personally get the feeling that this sense of distance make the viable as one based on “hearsay.” Is this something that you thought to do intentionally?

- It seems to be a fact that I like ceremonial type things. This ceremonial aspect seems to me to help free what is happening on the stage from the rules of Western theater. A festival is also a sort of ceremony or rite, and that kind of gathering gives the event a special quality, doesn’t it? I also like the kinds of events where the adults sit around drinking beer while the children put on some kind of performance they have rehearsed. In the Japanese immigrant communities as well, there are things like sports day events and Okinawan festivals. I don’t make an effort to try to join in and become a part of such events, but I like to watch them.

- Like the people who watch the festival from the outside as spectators, right?

- I don’t have any aversion to that kind of position as an onlooker. That is part of it all.

- With Valparaiso, the stage has 2-dimensional stage art only, but the audience area has furnishings like beds and a mock-up of a second-class cabin of the passenger boat and other things described in the stage script, and the staging leaves the audience free to choose where they want to watch the play from. How did that plan originate?

- A group called dot architects (*5) was in charge of the stage art and that idea emerged during talks with them. At first there was the idea of using a real car. But, the hall at the Kyoto Arts Center where the play was originally staged had a speaker’s platform, and the suggestion came out that it would be interesting to have the actors sitting up there, and the final stage plan gradually evolved from there.

- Does that mean that rather than starting from a director’s plan, the stage setting is decided in discussions with the other creators involved?

- Well, it is more like we also have discussions on some things. But, there are also times when I have a strong personal preference that I selfishly insist on. Usually I try not to state definitive decisions from the beginning. Often I don’t really remember who put forward an idea first and who made the final decision. The idea of having all the stage art as 2-dimensional wall art actually came largely from the fact that the theater critic Tadashi Uchino once introduced our Okazaki Art Theater company as a company that always have “ultra-dull and shabby” stage sets, so I thought that it would be OK for us to go with that ultra-dull and shabby image. (Laughs)

- Do you have any particular demands concerning the qualities of the actors’ acting?

- One thing I say often to the actors is that even if we have two or three months of rehearsals, not to think that alone is enough to work out all the issues. In short, even in the case of a young 20-year-old actor, those 20 years have not been spent completely for acting on stage, so there must be something more to their 20 years of life than that. I don’t know if it is right to say it like that, however.

- Does that mean you are not expecting to act out a particular role?

- No, I want them to act. But I don’t expect them to “become” their character. I tell them to “do” their role. Because there is no way that they can “become” their character.

- What are your thoughts about working with foreigners who come from different backgrounds?

-

I did Valparaiso using Argentinian actors, and understandably it was impossible for me to be in control of what they did. Naturally, what I thought I had been able to do as a director until then was impossible in this new situation, so I thought, “What can I do?” That changed my way of thinking a bit. There were some difficult aspects but, conversely, it also became easier in some respects, because I feel that it enabled the actors and director to stand on equal footing. With an all-Japanese cast you have the director up on a pedestal and the actors below in a top-down working relationship, but with the foreign actors I could leave it to them to do their thing (laughs).

I am not really trying to be the director, but I dislike being in a position where I am controlling the actors. If the actors don’t feel that they are owners of their roles and if they are not acting as they think they should, the play doesn’t work. On the contrary, if all the actors are in a mode where they are just waiting for instructions, I get irritated. - Are you saying that as a playwright you would ideally like to hand the script over completely to the actors?

-

That is difficult to say. The cast naturally wants to be given a free hand to do it their own way, so ideally I would just like to be able to let them do as they will with the script once I finish it. But when I see the rehearsals there are times when I don’t like the way some part is going and I want to change it. However, I don’t want the actors to change something on their own with asking me (laughs).

When I am writing something I don’t think much about the actors, but I can still feel there presence somewhere close by. Since I choose the actors before I have a clear image of what the play is that I will use them in, when I begin the actual directing of the finished script, I often find myself wondering why I have to do the play with this set of actors. The image is that the relationship is all secondary to the performance and the script. - Finally, we would like to ask you about what you see in the future and how you are feeling right now.

-

I feel that it is becoming more difficult for me to express things with a consciousness of the relationship between politics and art. I would like to not worry about that issue and not react directly in response to the various political issues of the day. I just recently spent a month in South America and I found that the things the people around me there were interested in were completely different from what I am concerned with, so I felt a physical distance had separated us. So, when I went to the social media to find out in Japanese what issues concerned them, I realized they were things that didn’t really interest me. I can’t keep up with the speed of the dialogue on the social media. So it may be that I have decided not to try to live at that speed.

I don’t know at all what is going to happen with my next work (*6) (laughs). If I keep trying to do things that my heart isn’t really into, the others are still here with me and if someone says something, things might change, and I feel that I am fine with that. Anyway we will see.

Yudai Kamisato

The Experiments of Yudai Kamisato

What is Theater as Messenger?

Yudai Kamisato

Director and writer. Born in 1982 in Lima, Peru, he grew up in Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture. In 2003, while a student at Waseda University, he formed the Okazaki Art Theatre. Based on the episodes he collects while visiting various places, he presents works on the theme of people moving and crossing borders. In 2006, he became the youngest director to win the Best Director Award at the Toga Director’s Competition for staging Desire Caught by the Tail (by Pablo Picasso). In 2018, he won the 62nd Kishida Kunio Drama Award for The Story of Descending the Long Slopes of Valparaiso. From October 2016, he stayed in Buenos Aires, Argentina, for one year on an overseas research grant from the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs. From 2022, he is a Saison Fellow II of The Saison Foundation. His plays have been translated and performed (including readings) in Seoul, Hong Kong, Taipei, New York, and London.

Interviewer: Masashi Nomura [theater producer and dramaturge]

*1 The Story of Descending the Long Slopes of Valparaiso

Premiering at the Kyoto Arts Center Auditorium in November 2017 as part of the main program of the KYOTO EXPERIMENT 2017, performed in Spanish with Japanese and English subtitles. The stage script was written based on episodes that Kamisato actually experienced or heard of in his travels in South America, Okinawa, Ogasawara, Australia and other places. The performers included the Argentinian actors Martín Tchira and Martín Piroyansky that Kamisato met while staying in Argentina, and the dancers Marina Sarmiento and the Brazilian dancer Eduardo Fukushima, who is a previous acquaintance of Kamisato.

The setting begins in a car at the coast in Valparaiso, Chile where the mother and son have come to scatter the deceased father’s ashes according to his wish. Apparently unable to accept the reality of her husband’s death, the mother refuses to leave the car to scatter the ashes. In a while two men who have come to assist in the scattering ceremony arrive. In the car, the mother continues to stare into space, while the three men sitting beside her begin to talk about people that remain in transition after death before crossing over into the other world, about how the human race in the distant past was driven by curiosity to cross the Pacific Ocean, about a total eclipse of the sun seen in Paraguay, about a man in Okinawa who continued to dig up the bones of the war dead, and the story of a man who runs a bar in Ogasawara.

The Pop-style stage art used paintings of scenery, cars and boats for the stage and the audience area was hung with the flags of the world’s countries overhead and props like a bunkbed, a 2nd-class boat compartment and a bar counter, and the audience was free to watch the play from wherever they chose.

*2 Okazaki Art Theatre

Formed in 2003 by Yudai Kamisato with the aim of directing his own plays. Because Kamisato owed money to his friend Seiji Okazaki at the time of the founding, Okazaki was named head of the company and his name used in the company name. Today, the company is operating from bases in Kanagawa, Tokyo and Kyoto as Kamisato’s personal theater unit.

*3 Toga Directors Contest

This performance contest for direction of existing plays has been held since 2000 at the Toyama prefecture Toga Arts Park (since 2008, it was reorganized as the Toga Theatre Makers Contest organized by the Japan Performing Arts Foundation). In 2006, Kamisato became the youngest winner of the Best Director Award for direction of the play Shippo wo Tsukamareta Yokubo (Desire Caught by the Tail /original by Pablo Picasso)

*4 Kyohei Sakaguchi

Born in Kumamoto in 1978. A writer/artist and architect, Sakaguchi graduated from Waseda University’s department of architecture. Having researched the lives of Japan’s homeless from the middle of the 2000s, he published a photograph collection title 0 Yen Houses (Little More Books publication) and Zero kara Hajimaru Toshigata Shuryoshushu Seikatsu (Urban type Hunter-Gatherer Life Starting from Zero / Kadokawa Bunko publishers), etc. After moving to Kumamoto shortly after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, he declared independence from Japan and took the post of Prime Minister of the new government in May 2011. From this experience he wrote the book Dokuritsu Kokka no Tsukurikata (How to make an Independent Country / Kodansha Gendai Shinsho publishers). He also writes novels, creates art and music in his widely divergent activities. Currently living in Fukuoka Prefecture.

*5 dot architects

Toshikatsu Ienari and Takeshi Shakushiro jointly established architecture firm, dot architects, in 2004. The base of activity is the Coop Kitakagaya in Kitakagaya, Osaka. In addition to architectural design and planning, they conduct research projects, site constructions, and art projects. In 2015 they exhibited at the Japan Pavilion in the Venice Biennale. They have also participated in numerous other arts festivals in Japan and abroad such as Kyoto Experiment and the Setouchi Triennial art festival.

*6 New work Happy Prince Fish

This newest work by Kamisato and the Okazaki Art Theatre premiered at Kyoto Experiment in October 2019. Kamisato began research after hearing about the problem of an invasion of a foreign species of fish like bluegills in Lake Biwa at a bar in Kyoto. Taking an island in Lake Biwa as the setting, and referencing the Noh play Chikubushima, the play includes episodes about the three traditional three-stringed instruments, the biwa lute, Okinawa shamisen and the Japanese shamisen and how they have evolved historically and regionally, while exhorting new ideas about things native and things imported, originals and mixtures the ecosystems of living things and the internal and external.

Yudai Kamisato / Okazaki Art Theatre

The Story of Descending the Long Slopes of Valparaiso

(Premiere)

(2017 at Auditorium, Kyoto Art Center)

Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

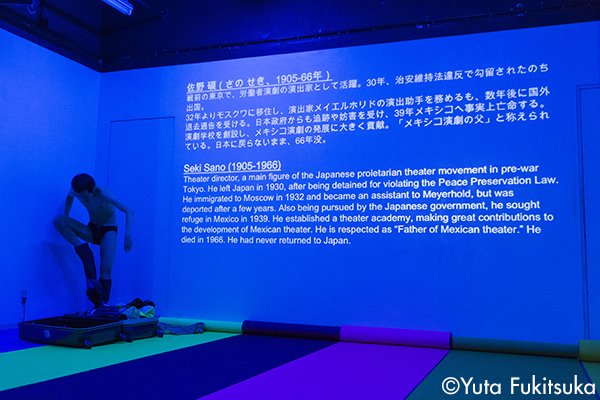

Yudai Kamisato / Okazaki Art Theatre

+51 Aviacion, San Borja

(2015 at ST spot)

Photo: Yuta Fukitsuka

Yudai Kamisato / Okazaki Art Theatre

Happy Prince Fish

(2017 at Kyoto Art Center)

Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

Courtesy of Kyoto Experiment

Related Tags