- Let us begin by congratulating you on the Kishida Award and the 15th anniversary of the Nibroll. We are told that you began dance when you were 17. Would you tell us what led you to that?

-

I come from Ehime prefecture, where I went to Imabari Minami High School and was a member of its Manga Research,

Igo

(chess) and Nature Experience clubs, all of which were what you could call the “go home early” (non-serious) clubs. My sister two years older than me was the captain of the dance club, and when she graduated there were so few members left that the club was in danger of being dissolved. In the summer vacation of my second year of high school she had me watch the movie

Chorus Line

everyday and tried to convince me that I liked dance too. That’s how I became a member of the dance club.

Of course I couldn’t do anything alone, so I got a few of my classmates to join too, and it just so happened that a dance teacher came to our school that year. She was a very devoted and passionate teacher, and since we had no experience in dance at all, she gave us ballet lessons every day. Ehime prefecture happens to be big in dance and when we entered the high school creative dance contest with a work that we had created on the theme of [Ehime poet] Masaoka Shiki, we won. That made our teacher even more determined to make dancers of us with intense training, and when we entered the NHK (national television network’s) National High School Dance Contest, our work “Hito Oni” that I had choreographed based on a folk tale about a meeting of people and demons, it was chosen as one of the winners.

At the time, I was also learning painting, so I had a hard time deciding what course to pursue in college, dance or art. It happened that a new Dance Department had just been formed at the Osaka Physical Education University, and although I was never good in physical education, I applied to go there. I had expected that there would be a lot of students applying for that course, but when I got there I turned out there were only two of us. That started another period of intense training! (Laughs) I had classes in ballet, modern dance, jazz dance and dance composition, and I was also taught Limon Technique by Betty Jones and dance therapy by Ruth Solomon, who came from America to teach at our university. Since I was also a member of the dance club, I was immersed in dance from morning till night.

In my junior year I went to the U.S. as an exchange student and studied in the Dance Dept. of Duke University in North Carolina and also went to the American Dance Festival (ADF) at the University of Hawaii. In graduate school I wanted to study ethnic dance and went to do research in Brazil, but it happened to be a time of serious security problems and I was unable study as I had hoped. That led to a change of heart and I went to film school for a year. - After being so immersed in dance for some time, what brought on this change in direction?

-

I wasn’t confident that dance held a future for me, and although one of my college professors had recommended a career in teaching, I didn’t feel I had the temperament or inclination for that. I had always liked film and I happened at the time to see a film school advertisement in a newsletter saying, “One year of study can make you a professional.” It made me think that perhaps I could make a living in the film industry and do dance as a second interest. So, I enrolled in film school.

After graduation I was given an introduction for a job at a TV station, in its news department. It was a time of big news stories like the Great Hanshin Kobe-Awaji Earthquake and the series of incidents surrounding the Om Shinrikyo cult that kept us so busy that there was of course no time to do any dance. The work was interesting in itself but when I stopped once to calculate how much time I was spending on the job compared to my pay, I realized that I was working at an hourly rate of only about 120 yen (just over $1.00/hr). I knew I couldn’t go on like that. Then I started finding excuses to quit, saying that it wasn’t news but drama I really wanted to do. But then I would change my mind and say it wasn’t drama but film I wanted to do. Each time people would give me introductions that I didn’t follow through on, so I was being quite irresponsible and causing people a lot of meaningless effort. Finally, I said I wanted to do dance and actually quit my TV news job, but by that time the people around me were really beginning to worry about me.

At that point I entered the Arts Studio of Kanagawa (ASK), which had been newly formed by the Kanagawa Arts Foundation in 1997. Among the ASK members were the Dance Theater LUDENS leader Takiko Iwabuchi and Dumb Type’s Yuko Hirai. At the time, prominent choreographers and Japanese dancers from important international dance companies like Forsythe and Rosas and the Wuppertal Dance Theater were brought in as instructors at ASK, so we were able to learn what was going on in Europe. Also, was encouraged when the Rosas dancer Fumiyo Ikeda complemented me on one of the works I created.

Around the same time I got an offer from our film school to do an independent film as a graduate of the creator department. But, rather than making a small-budget film, since I had been doing dance I thought it would be better to do a stage work composed of dance and video art. That is what led to the start of the Nibroll activities. Our first work after forming Nibroll was Pulse , which we performed at the Nakano Studio Actre theater in 1997. The original members of the group were graduates of our film school. Now, the only one of them that remains is the visual (video) artist Keisuke Takahashi. None of those original members at the time had experience in stage arts, and although we had only three days of performances scheduled for that first work, it wasn’t finished by opening day and we had to send the audience home. And, when we did actually start the performances there were mistakes that made us stop the performance and start over from the beginning. It was really a mess!

When we were thinking of a name for our group, my grandmother said it would be good to have an “r” sound in it, so we all thought of names with “r” sounds in them and finally decided on Nibroll. It was the name of the drug used by famous Japanese novelists Osamu Dazai and Ryunosuke Akutagawa and the intended meaning was that you wouldn’t need a drug like that, because you could get the same excitement by coming to see our stages. - The latter half of the 1990s when Nibroll was starting out was a time when young artists were experimenting with different types of contemporary dance with the common theme of confronting their own physicality. There were new small performance spaces for dance and they were organizing showcases where those artists could perform. In the early days, Nibroll was that kind of company and you began to get attention with your second work, Hayashi’nchi ni Iko (Let’s go to HAYASHI’s House) you did in 1998 and the following works Tokyo Daiichi Shiei Pool (The TOKYO Civil Swimming Pool No. 1) and Chushakinshi (NO PARKING). What were the ideas behind the works of that period?

-

Many of the members of ASK had been overseas and I had the strong desire to create works that could be shown overseas as works from Japan that originated in the city of Tokyo where I lived and its unique environment. However, neither myself nor any of our other dancers had any especially outstanding dance technique, so I thought about forms of expression that could equal any quality of technique. In these three works you just mentioned, I had decided to create works whose strength lay in their composition of excerpts of elements of daily life in contemporary Tokyo of that day.

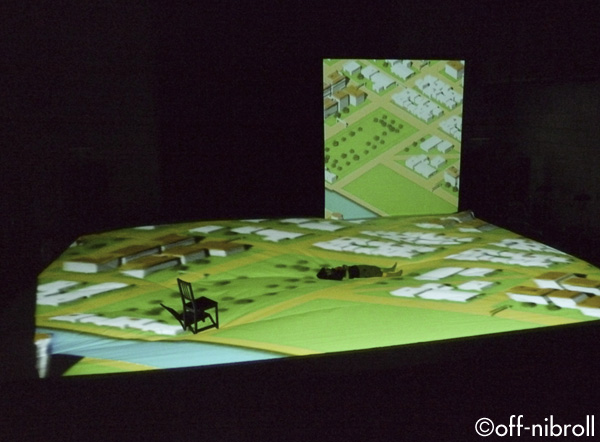

In the work Let’s go to HAYASHI’s House that we performed at Session House in 1998, I wanted to show very real impressions of people of my generation living in the city of Tokyo. So, we used a lot of overhead views of the city and had the act of the performers walking around on these images of the city itself become a form of dance.

In 1999’s The TOKYO Civil Swimming Pool No. 1 I took that concept one step further and attempted to create something that would express the position we find ourselves in today. Since Tokyo is officially not a City ( shi ) but a Municipality ( to ) there is no such thing as a “civil” pool in Tokyo. But, both myself and the other members of Nibroll grew up in regional cities of the type where you had commercial districts where there were convenience stores and the local McDonald’s alongside the small mom-and-pop vegetable shops and fish shops of the shopping street. So, the “TOKYO Civil Swimming Pool” in the title was meant to imply that we were people who grew up in cities outside the great Tokyo metropolis. I wanted to communicate the fact that our existence was like that of someone just splashing their feet in the water of a shallow pool where there was no danger of anything harmful happening. So, around the set I had lots of water set up. But it was set up so they it was always caught in cups. And the concept was to end the performance before the water overflowed.

For our 2000 work NO PARKING , I created a work for the first time with actors who had no dance experience. I chose people with a variety of physical characteristics and I wanted to use them to create impressions of the ordinary people you will find in the city. Also, I had become a bit tired of dancers who were only interested in dancing, so I also wanted to gather a group of members who were motivated to create a work together and work with them on the basic preliminary stages of the movement, having them give input from the beginning of the choreographic work. It was a time when my grandfather had just died and I was thinking various things about the idea of people returning to the soil. I wanted to give expression to the fact that even in the city today paved in asphalt, we are still living on top of ground where the dead of the past are buried. In the performance you have people whirling hula-hoops around and people jolting others and asking if they are all right, and these are movements that resulted from the process of trying to work actual scenes of the town into dance. - In Nibroll works we often see such everyday body movement or gestures appear along with added speed and violence.

-

I am always searching for new forms of expression that can become contemporary dance, and when you look at the city through those eyes, you get many images of how harsh or cruel people can be to each other. You see things like the way excessive care or concern can be oppressive and drive people to desperation or how violent people’s influence over each other can appear. I remember talking to the members of the group about the possibility of finding these aspects of human interaction in the city of Tokyo. The metropolis has a its own pace, its own speed, if you don’t live at its pace you get left behind, and even today I feel that this great metropolis Tokyo can not only leave you behind it can make you feel it is destroying you.

I should note that at the time of these works there was rapid progress was being made in digital technology, making it possible to easily create animation and music on a PC. Projector performance was also advancing dramatically, so NO PARKING became the first work I created with a full consciousness of visuals as part of the composition, and that would connect to later works. - Two years after the launch of Nibroll you participated in the Avignon Festival Off program. Did you have the intention of performing internationally from the beginning? And, what was the audience’s reaction like to that first overseas performance?

-

My younger brother Mitsushi had started saying things like, “Isn’t France where it’s at in dance?” And, when we looked into it we found out that Avignon Festival Off was a fringe festival and apparently you could participate in without necessarily receiving an invitation. So, we contacted the smallest of the festival’s venues, the Theatre du Pirouette, and they said that if we were coming from so far away they would let us perform free for a month if we didn’t mind a midnight time slot from 12:00 to 1:00 am. Fortunately we were also able to get a grant from the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture, so we went and performed

Let’s go to HAYASHI’s House

. Many of the people in the audience had an image of Japan as a country of traditional ways, so after they saw our performances we got comments like, “I see that you guys eat hamburgers too.” I believe that through our dance they got a feeling for what contemporary Japan is like. For the first performance, the audience was only three people, but the number gradually increased, which was encouraging to see. Anyway, it was a good test and good training for us.

At the Theatre du Pirouette we won the Newspaper Prize, and the next year we got a grant from the Japan Foundation and were able to go an perform The TOKYO Civil Swimming Pool No. 1 for a month. The third year the second prize at the “The Millennium Culture and Art Festival Award” sponsored by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government was an invitation to Avignon Festival Off, so we were able to perform NO PARKING there for about three weeks.

During those long runs we were able to go and see a lot of works performed in a short time. By seeing stages by artists like Jan Fabre, Josef Nadj and Pina Bausch, the members of Nibroll got a direct experience of the possibilities of physical expression and it inspired them to strive to do more in terms of physical expression. In 2001, NO PARKING won the “National Advisory Panel Award” Bagnolet International Choreography Contest, which meant that they were recognizing what we did as dance. At the San Francisco Butoh Festival, our work was described as a new kind of Butoh. After that we were invited to the Kampnagel Festival in Germany and the Portland Dance Festival, enabling us to tour overseas with our work. - The following year, 2002, you were commissioned by the Park Tower Hall “Next Dance Festival” to do new works for three years. With the three works COFFEE , NOTEs and Dry Flower you created on that commission, what did you hope to communicate to the audience?

-

Until then, we had only created works for small performance spaces as what is called a “small box company” in Japan, so it was a bit intimidating to now be doing works for a big hall like Park Tower Hall, but we were determined to give it all we had. By that time I had gotten away from the concept of expressing the contemporary life of the city of Tokyo and my interest had shifted to the concept of “boundaries.” For

COFFEE

, the age of the Nibroll members now ranged from the late twenties to the early thirties and there had been a lot of events that constituted turning points for them. In other words they were at the fuzzy boundary between youth and adulthood, which came also as a period when they began to drink coffee. In the work I wanted to express that relationship. Around that time I had a clear consciousness of wanting to create good works that would show the potential of dance to as many people as possible. We had reached the point where we were able to seek the expertise of people outside our group when we lacked the technical skills to realize the ideas of the original members of Nibroll, and for the first time we had SKANK contributing music for the first time.

Our work NOTEs of 2003 was our first international collaboration. A request came from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts to have a Japanese group do a collaborative performance with the famous Attack Theater company of Pittsburg, so Nibroll went to Pittsburg for about two months to participate in creating a joint work. It was based on a theme we had been talking about since the last work. I wanted us to think about Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution (which prohibits an act of war by the state) as a form of boundary for we Japanese who live with no real sense of peace and yet take no action. We used costumes with an Article 9 motif and on the same stage we had performers from the two former enemy nations Japan and the USA with their differing bodies with different backbones, and in the creative process we had a clash of our different views on history. We were also unable to find common ground regarding the use of the body and music, but we still went on to tour seven American cities with the resulting work. Having thus been a case of “indigestion,” we then went on to create another version using only Japanese dancers titled NO-TO , which we performed at the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale.

The 2004 work Dry Flower involved an aesthetic boundary and a boundary of dance that involves seeking beautiful form and then having it disappear in an instant. Since we had been told all along that what Nibroll does isn’t dance, this was a work where I wanted to consciously show the dancing body and dance movement. After this work Nibroll activities were suspended for one year from 2004. That is because I went to New York for an extended stay on a fellowship from the Asian Cultural Council (ACC).

We resumed Nibroll activities from 2005 and presented no direction (2007), Romeo OR Juliet (2008) and THIS IS WEATHER NEWS (2010). The works of this period were large-scale productions motivated by a desire to reach a larger audience with an orientation that was different from the original Nibroll orientation toward searching for new possibilities in dance.

In the meantime, the directions being pursued by each of our members has gradually become different and I feel that Nibroll is now approaching a turning point. Until now the multimedia orientation has been at the forefront in our works, but at the same time you can’t ignore the importance of physical expression in Nibroll’s work. After THIS IS WEATHER NEWS , we have had a change in our members with Takuya Kamiike joining as visual artist (stage art), and for our next work I want to confront the question of physicality working with Takahashi, SKANK, Kamiike and the dancers. My feeling is that from now on I want to tackle the difficult question of what social relevance physical expression can have. - Initially, Nibroll called itself an “artist collective” with artists from a number of different fields working together. What did your actual creative process involve?

-

To begin with, each of the members were already busy with activities in their individual fields, so it was not a situation where any one of us could become the person in charge of overall creation. As a result, we used a division of labor, and that was the meaning of the “collective.” That resulted in the give-and-take and sometimes conflict occurring between the creators serving as the driving force in the creative process based on.

For example, our most recent work THIS IS WEATHER NEWS that premiered at the Aichi Triennale 2010 was actually a further development of my solely directed work Aa nattara, ko naranai performed at the [Yokohama] Red Brick Warehouse Hall. First of all, the core members of Nibroll (staff in video, music, costume, stage art, etc.) gathered to discuss what issues were there in society today and what approaches we could take toward them in order to attract a large audience. For example, if I say, “If such-and-such happens, there won’t be such-and-such, and if that happens, this won’t, and that bothers me.” Then the members will start researching for examples. One member comes back and says that the world is starting to run out of water, and another says that there is a rapid increase in the number of grasshoppers, and as we all discuss things ideas are born. That stage of the creative process goes on for about six months.

After that the various creators work separately, the dance people on dance, the video person on visuals, etc. Then we bring these elements together in the studio and exchanges take place, such as, “If the video is shown at this point the dancers can’t be seen, so will you take that part out,” and if the opinions of the video artist and the music director don’t agree, I doesn’t really concern me. With a new work we will begin working together on it in the studio during the final three months before performance date. During that stage we look at each others’ parts and the ideas may change as a result, and we may make adjustments to bring things together. After that process the work has generally taken final shape about one month before the opening performance.

In the past there was quite a lot of disagreement and conflict between the creators, but since we have been working together for 15 years the frequency of such conflicts has decreased considerably. In a sense, I think that is actually a bit of a problem, but it has also led to realizations. - In order to continue creating works for such a long time, having a good creative environment and access to studio space is certainly a very important issue.

- From 2001 we were given access to the Morishita Studio thanks to ongoing support from the Saison Foundation, and in the last five years we have received support as resident artists at the Steep Slope Studio.

- Next we would like to ask you about solo activities you started in theater in the form of the MIKUNI YANAIHARA Project in 2005. Around the same time Toshiki Okada began presenting dance works he had choreographed and it seemed to establish a creative connection between small theater works and dance. What led you to begin working in theater?

-

In 2003, Nibroll participated in the Guardian Garden Theater Festival with a performance of

NO-TE backside

, but in fact, the years I spent in New York in 2004 on the ACC fellowship led to some encounters with theater that truly came as a shock to me. One was a performance of

Three Sisters

by the Wooster Group that began with a drawing of sticks to see which actor would perform which role, and the other was a work titles

Forsythe

that used an interview with choreographer William Forsythe himself. As the film of the interview was projected, a group of people who had absolutely no experience in dance are talking on and on about how they are going to try to become dancers, but of course they can’t dance. I didn’t understand the [English] lines well but I found the physical expression in the play to be fascinating, and it made me think that if this can be considered theater, I would like to try my hand at it, too.

Then in 2005 I got an offer to do a performance for the opening of the new Kichijoji Theater in Tokyo and I agreed if they would let me do a theater piece. What I created for that as the first MIKUNI YANAIHARA Project production was the work Sannen Nikumi (High School Senior Class 2). - With Nibroll you had already used the physical expression of non-dancers, so were you intent on exploring the dramatic aspects that exist within dance?

-

In terms of such “dramatic aspects that exist within dance,” Pina Bausch, for example, said she was consciously introducing common things from daily life into dance. In contrast, the stages of the Wooster Group involved concerted efforts to remove the daily-life aspects in drama.

In short, these are cases of thespians and choreographers approaching the commonplace and daily-life elements in completely opposite ways. The choreographer introduces commonplace moments of surprise into dance, like the moment when you plunk down at a desk or the moment a chair falls over. Normally we would say, “Oh!” in surprise at a moment like that, but in dance you express that surprise in movement, don’t you? Of course, even in dance it is possible to use vocal expression, but generally we will use a motion that makes the viewer realize that the person has just experienced a moment of surprise. The act of striking something in a way that creates a noise is also an extension of movements that express surprise, and rather than being the product of an attempt to translate the surprise into movement, it can be something that comes out naturally.

In theater it is the opposite because from the beginning you have a script that includes depictions of commonplace aspects of everyday life and to that you have to introduce completely different perceptions of reality [to make it theater]. So, when I do theater, I feel it is meaningless to have the actors talking in colloquial, everyday fashion, right? That’s why I have them shouting or make them run when, otherwise, there might not be a need to. They are a good number of directors who apparently feel the same way. For example, [Toshiki] Okada will have his actors move and speak as in real life [rather than creating fictional daily life scenes], and Kohei Tsuka has his actors practice speaking their lines while doing sit-ups and dispensing with any type of pretense or show. I believe that is the result of the different sense of reality each of these directors has. - I believe that in both dance and theater you are pursuing raw reality as you perceive it, but how about as a playwright?

-

[Butoh] artists like Min Tanaka and Akaji Maro have said that it is difficult enough to speak lines that others have written, but writing your own words is even more difficult. In the past it was unthinkable to have dances speaking lines on stage, but today it has become commonplace. That has created the need to bring words with true originality into dance and made it necessary for choreographers to choose their words carefully.

Because I was doing dance from my youth and learning a variety of dance technique, my own forms of movement come out naturally, but when it comes to words it is more difficult for me. And, when it comes to writing plays, it is not something I am used to, or studied, and I haven’t read a lot, and since I haven’t read enough, it takes a lot of time for me to write. It is only recently that I have become able to search for my own words like I search for new phrases of physical movement in dance. From now on I want to be able to write down the words that come out from within me. - Watching your play, the length is about 90 minutes but the script is very long and the lines spoken so fast and overlap so we can’t really hear what the actors are saying at times (laughs). Is it directed that way intentionally for a specific effect?

-

Usually the script for a play is about 35 to 50 pages in length, but mine are about 80 to 100 pages. When I write, the actors and their character assignments are not yet decided and I am writing with just an image of the different roles, so when you read it as text you get an idea of the kind of story it tells, but when you put it on stage [the actors] say often that they don’t understand it.

In fact, with Sannen Nikumi , up until three days before the opening performance the play had a running time of three and a half hours. The producer asked that I cut it down to at most two hours, and I tried but I just couldn’t cut it. Then Takahashi said we could increase the speed to cut the time, so we tried to see how fast we could make it in those remaining three days. Each day we timed it and it got faster, and finally it was down to one and a half hours. The fact that it was then hard to understand what the actors were saying added to the sense of speed in a way that people said was interesting. If so, all the better. So I decided to do it that way, and I made that a new kind of style.

Maemuki Taimon , which won the Kishida Drama Award, premiered in December of 2010 at the Shakespeare Competition. Then I revised it in 2011 for performances at the [Komaba] Agora Theater and other places. The award made me happy, because it showed that my work had been recognized as a play. In the performance the actors are speaking very fast, but there is also the question of how the actors use physical language to convey to the audience the contents of the lines they are speaking. When I am creating a theater work I am always looking for things that go beyond words. I am often told that I should believe in words more, but words and languages are different throughout the world and each language has its own beauty. I want to create theater works that lightly and effortlessly transcend those words. - You have another project launched in 2004 involving just you and your visual director [Keisuke] Takahashi that you call called “off-nibroll.” I imagine that you started it as a versatile, easily applicable unit and you have in fact applied it on a large scale for a number of international art exhibitions and collaborations with overseas artists. Has it led you to new discoveries about the possibilities of combining video and dance?

-

The concept behind our off-nibroll activities is one of art and it affords an ease of footwork, so we can say the two of us will go [to an exhibition] and set up an exhibit and can have a performance ready in about thirty minutes. And, since we have been doing it, it has brought me realizations about new possibilities for bringing together video, technology and the body (physical performance). It began with the work

public=un+public

we premiered at the BankART 1929 in 2005. This was a collaborative work that we created with Jo Lloyd of Australia’s Chunky Move Studio in residency stays in Yokohama and Melbourne. It was born from the idea that the nature of extremely private spaces and very public spaces can be reversed depending on the conditions created there, and if people can transcend the meanings of those spaces and meet there, it can perhaps bring about better understanding between people. This project is continuing in various countries and cities around the world, and I want it to be a platform for collaborating with more overseas artists.

In the end, activities like this that are an outgrowth of Nibroll are connecting back to Nibroll in various ways and places. For example, our next [Nibroll] production will be a work based on the off-nibroll work A Flower that we created during an artist residency at Seoul’s National Museum of Contemporary Art. At the time of last year’s devastation 3.11 earthquake and tsunami (Great East Japan Earthquake, March 11, 2011) I had returned to Japan to do a workshop at the Kichijoji Theater in Tokyo, and this work [ A Flower ] was one that I created as the result of my thoughts at the time about why the living give a flower in memory of the deceased [at Japanese funerals, etc.] and the feeling that I had to memorize with the body and records the things that were happening and make a proper work from them.

Many artists overseas reacted very quickly to the 3.11 disaster. The Vietnamese artist Tiffany Chung with whom we had collaborated in an off-nibroll work last year contacted me to say they were having a charity event for the 3.11 victims at a gallery in Ho Chi Min City and they wanted me to submit a work. I had not done anything connected to 3.11 but here were artist overseas of my generation who were all trying to do things for Japan. It made me feel how unresponsive I had been and made me determined that now I have to do something, so I did a charity reading with director/playwrights Akio Miyazawa and Yoji Sakate at Tokyo Wonder Site. With the belief that I had to commit the things I felt to memory immediately, I have been recording things in detail over the past year and I want to put them together into works to present at the 2012 YCC and Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale. - I believe that you are now an artist who pursues your own visions of reality and explore movement in the areas that interest you and realize your ideas in ways that have won you international recognition. You are also contributing to the nurturing of the next generation of artists though your capacities as artistic director of Agora Theater and by running a studio. As my final questions, I would like to ask what you want to communicate to people of the next generation, and what you think is needed in Japan’s contemporary dance?

-

Doing performance tours with

COFFEE

as a repertoire work in countries around the world, I feel that it also uses up a lot [of energy, resources, etc.]. Compared to places like Europe where there is a lot of national support available for the arts, I feel that Japan lacks the base to nurture and support dance companies that can truly represent our culture [abroad]. How to change that situation is one of the big issues we confront.

My desire to have people see my stages, feel disturbing things in them and come away with questions in their mind is the same as when I first started out in dance. In order to help create an environment where choreographers can create works with new sense of value they have found and then have large audiences see those works, I am also doing art exhibits and theater. I believe that physical expression [dance] is a valid form of contemporary artistic expression, and of course I believe that physical [body] movement translates into words, and so I want to cross the boundaries of artistic genre and spread interested in dance in ways that will attract larger audiences.

To young people I want to say that there definitely are new forms of expression to be found in dance if they remain dedicated and don’t give up. And, because I believe that they are already crossing over the boundaries of genre more than my generation has, I want them to find their own forms of contemporary dance that are different from Butoh and different from Western contemporary dance. To do that, I want to say that we can work together toward that goal.

Mikuni Yanaihara

Calling out with words and the body

Mikuni Yanaihara’'s pursuit of reality

Mikuni Yanaihara

Born in 1970. In 1997, Yanaihara joined with fellow artists in the fields to launch the performing arts company Nibroll and has served as the group’s representative and choreographer since. With a unique choreographic style based in everyday movement and expressing the atmosphere of contemporary Tokyo, she and her works have been increasingly invited to perform at overseas festivals. In 2005, she launched the Mikuni Yanaihara Project with performances at the Kichijoji Theater in Tokyo and commenced activities as a playwright and theater director. In 2012, her play Maemuki! Taimon won the coveted 56th Kishida Drama Award. Paralleling her activities creating stage works, she works with video (visual) artist Keisuke Takahashi to create video art works under the unit name “off-nibroll.”

Interviewer: Matsue Okazaki / Representative, Offsite Dance Project [NPO]

MIKUNI YANAIHARA Project vol.5

Maemuki! Taimon

(Hey Timon, Let’s Think Positive!)

Written, directed and choreographed by Mikuni Yanaihara

(Sep. 2011 at Komaba Agora Theater)

Photo: Nobutaka Sato

Nibroll

COFFEE

Choreographed and directed by Mikuni Yanaihara

(Feb. 2002 at Park Tower Hall, Shinjuku)

Photo: Yasuyuki Masunaga

Nibroll

Romeo OR Juliet

Choreographed and directed by Mikuni Yanaihara

(Jan. 2008 at Setagaya Public Theatre)

Photo: Kenki Iida

Mikuni Yanaihara Solo Dance

Aa nattara, ko naranai

(it is not so because it is so.)

(2010年3月/横浜赤レンガ倉庫ホール)

Photo: Someido

(Mar. 2010 at Yokohama Red brick Warehouse Hall)

Photo: Someido

https://precog-jp.net/

MIKUNI YANAIHARA Project vol.3

Ao no Tori

(The Blue Bird)

Written, directed and choreographed by Mikuni Yanaihara

(Sep. 2007 at Kichijoji Theater)

Photo: Nobutaka Sato

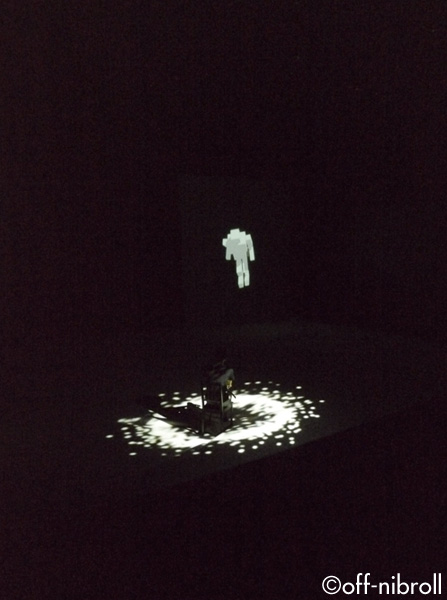

off-nibroll

one into 2 is

(2011, video installation)

off-nibroll

public=un+public

(2004, video/photo/installation)

off-nibroll

dried flower

2004年 video / photo / installation

SNOW Contemporary

(2004, video/photo/installation)

Related Tags