- I saw the performance of Le centaure et l’animal (The Centaur and the Animal) at the GREC festival in Barcelona, Spain this July. The work was a collaboration with Bartabas, the world renowned director for the Zingaro Equestrian Theatre. As we know, the centaurs are half human, half horse creatures from Greek mythology. It was a very poetic production in which Bartabas appears on the sand-covered stage on horseback in the form of a centaur with the Chants de Maldoror of Comte de Lautréamont being recited in the background in a stage where you perform as the Animal.

-

Thank you. When you first told me that Bartabas was interested in my dance back in 2009, I went to see the

Battuda

production performed on the Zingaro company’s second tour of Japan. At that time I gave Bartabas a DVD of my dance performances. Some time after that I received the offer from him to do a collaboration.

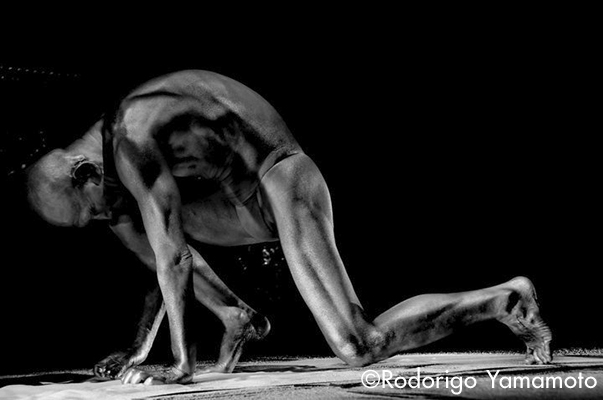

When I heard that he watch the DVD and was amazed by the way I was able to move like an animal on all fours in one of the pieces, I realized he must be serious. So, I decided to accept the offer. - Before seeing the performance I was wondering what the meeting of two such different genre as equestrian theater and butoh would be like. What I saw in the actual production was the two being performed in their inherent styles with almost no change [laughter], and it was quite thrilling to watch as the “distance” between the two would at times become close and at other times drift apart. When did this work premiere?

- It premiered in Toulouse in September 2010 and then went on to Normandy, the Chaillot Theater in Paris in December where the shows were filled to standing room only every night for three weeks. In 2011 we performed in France at La Rochelle and Montpellier, then in London at Sadler’s Wells and then in Barcelona, Spain and in Torino, Italy. From December into next year (2012) we will perform in three cities in France.

- I would like to ask about how you became involved in dance. In 1969 you began studying butoh under the late Tatsumi Hijikata . Did you have any involvement with dance before that?

-

I think there are two important experiences that relate to my becoming involved in dance (butoh). One is my experience of dead bodies. I lived near the seashore at Shonan (Kanagawa) until I was five. There, I had a couple of experiences of being washed into the sea by a wave and nearly drowned. It was also a shore where the bodies of people who had drowned washed up on the beach. The body would be lying there covered by a grass mat (

goza

) until the authorities came for it. From those experience I got an image of myself lying under a

goza

mat after taking in a lot of sea water and drowning.

The second important experience could be called the “experience of distances.” It is experiencing the other. It is the fear of contact, which can also be expressed by the word “shame.” Even if there were moments of physical contact when I would be pulled into a festival at the local shrine, in a case like the folk dance class at school, I couldn’t touch the hands of the girls. If our hands did touch I would begin shaking and blush with embarrassment, it was as if my body belonged to someone else. It was an inexplicable feeling of distance from my body.

In terms of things more related directly to “dance,” I loved rock ’n roll from the time I was in elementary school and used to the US Billboard Hit Chart broadcast by the FEN radio station [of the nearby US military bases] or black music. My idols were Ray Charles and Sam Cook. In high school I used to seek into the modern jazz cafes in the Shinjuku’s entertainment district in Tokyo, and at night I’d go to the go-go dances. I was really into the dancing of George Chakiris and Rita Moreno in West Side Story . - That sounds quite different from the image we have of Ko Murobushi today! (Laughs)

- I am a member of the Baby Boomer generation. With events like America’s Civil Rights Movement and France’s May Revolution, everything around us became very political when I was in high school. That was the mood of the whole era.

- It certainly was an era of upheaval. In Japan we had the violent takeover of Tokyo University by student activists at that time in 1968 into ’69.

- I hear that [Tatsumi] Hijikata was a member of the rugby team at Akita Industrial High School [in the far north of Japan], and I also happened to play on our school’s rugby team for one year. I was a back. I had some friends around me who went from doing tackles on the rugby field to forming scrams in the student demonstrations when they charged the police walls. But, I kept a bit more distance from it all and spent my time writing poetry while listening to John Coltrane’s jazz music. In college I used to go out for amusement and one time when I followed along to the demonstrations concerning the Oji Military Hospital [US base hospital] wearing wooden sandals [popular among demonstrators], I was tailed afterwards and arrested. I spent five days and four nights in jail for that. It was an era when there was a strange crossing between the extreme left and the extreme right. When I think back about my encounter with butoh, I feel it was an extension of the mood of that time, what you might call “pop avant-garde,” and avant-garde experimental activities like High-Red-Center’s [artist group of Jiro Takamatsu, Akaishi and Natsuyuki Nakanishi: *1 ] plan to bomb the Yamanote train line [metaphorically] and the imitation 1,000 yen bill incident were very stimulating for me, even before I encountered Hijikata and butoh. When I was coming of age, it was an era when everything seemed to be disruptive, polarized and full of ambivalence. We wanted to be involved in all kinds of things, but we were also told that we couldn’t do this and we couldn’t do that. If you were a man you also wanted to be a woman. There is a word chaosmos that is a melding of chaos and cosmos, and it implies that prior to becoming either a man or a woman, we were a life form that has lived through multiple sexes and more ambiguous choices. With regard to the body as well, we can experience chaosmos when we are concentrating. However, when we return to daily life situations we classify things and say that this person is a man, he is Japanese and in the social context he writes things in beautiful Japanese prose. And at the time, the desire to reverse that kind of simple classification and experience things on a higher, more subtle and sensitive level was expressed using the word nikutai (the flesh-and-blood body written with the Chinese characters for flesh and body, as opposed to the more commonly used word shintai ( karada ) with its stronger nuance of one’s body). Anyway, it was a time when it was popular to use the word nikutai .

- At that time the word shintai was rarely used, it was almost always nikutai , wasn’t it? That is why Hijikata titled his 1968 work Hijikata Tatsumi to Nihonjin –Nikutai no Haran (Tatsumi Hijikata and the Japanese – Revolt of the Body), isn’t it? [Playwright/director] Juro Kara also used the word nikutai often.

- Yes, that’s true. Hijikata-san talked about the “stray body.” I think that the word nikutai was being used in the sense of the corporeal body that includes things outside the realm of thought or intentions, which means that it includes things beyond the emotions and dark elements rejected by society and history, the body that has been discarded as something unproductive. It was an era with intricate dynamics at play, with the institutional dissection of the body and dissection of the self flowing into both the united student revolt movement (Zenkyoto [ *2 ] 1968 – 69) and Yukio Mishima. Hijikata’s 1968 work Tatsumi Hijikata and the Japanese – Revolt of the Body was symbolic of the times. I was a college student at the time and we felt that it fit the times, was actual and an exceptionally fashionable anomaly. It was performed at the Nihon Seinenkan and there was a black horse tied up by the entrance. We didn’t know why there would be a horse there. And there was also a row of congratulatory flower wreaths, like the ones put up when a new pachinko parlor opens. That gave it a garishly decorative atmosphere.

- So, you felt that Tatsumi Hijikata and the Japanese – Revolt of the Body expressed something of the mood of the times and it had a big impact on you personally?

- Yes. It was the time I was reading Nietzsche and Antonin Artaud and Becket, and I was beginning to become oriented toward forms of expression that didn’t rely on words. So, I had started thinking about dance. A group of university friends and I had a happening and event group we called Mandragora, and that was when I heard from Natsuyuki Nakanishi of High Red Center about a performance by Hijikata, who was doing the same kind of thing with dance.

-

At that time people didn’t call it performance, they called it happenings, didn’t they? It was a time when “happenings were the thing and they were staged without concern for the former distinctions between theater, art and dance, and in an “anything goes” atmosphere people tried all kinds of ways to attack the social establishment and government. This was true not only in Japan, as the same things were happening in the major metropolitan areas of all the capitalist countries, and you were right in the midst of it, weren’t you?

I believe you decided to study under Hijikata in 1969. How did you ask him to take you in as an apprentice? - It was in the spring just after Revolt of the Body . I wanted to have contact with the actual person, so I went to the Asbestos Hall [Hijikata’s studio] to meet him. Bishop Yamada was with me. When we met him, Hijikata said, “OK guys, I just happened to be looking for some bodies ( nikutai ) for an orgy.” We replied, “We’ll do anything.” It happened that Hijikata was in the midst of filming for a Toei movie and that was what the orgy scene was for. (Laughs)

- What was the name of the movie?

-

Onsen Ponbiki Jochu

(Hot Spring Spa Maid Pimps). (Laughs). The director was Misao Arai. They gave is fare for the Bullet Train and we went to join the crew at the Toei Kyoto Film Studios. There, we went out on the town every night with Hijikata and drank at cheap bars with Yoko Ashikawa and Koichi Tamano. That was my first “Hijikata experience.”

Watching Hijikata, he had what you might call a melancholy in which he created happenings on a daily basis. He performed one-man acts one after another, and it still fills me with wonder when I think about how a man could be so dramatic in that kind of style. One of the Hijikata phrases that I like is “ Yaban de sensai ” (Savage subtlety/sensitivity), and it would go off in him on a daily basis. We would be drinking and having fun, and then he would do something to create a rift, you might say, abruptly and all of a sudden. Perhaps it was his way of changing the tempo of things, but he would do something like suddenly breaking out crying. And that would surprise everyone around him, as you can imagine. To me, that in itself appeared to be his dance. It had the appearance that this was Hijikata’s form of improvisational dance that was even more fascinating than formal dance works he created. - How long were you actually with Hijikata? Was it just for the movie Onsen Ponbiki Jochu ?

- After that I acted in another Toei movie. It was Kyofu Kikeiningen (Horrors of Malformed Men) directed by Teruo Ishii and it is has become sort of a cult film today. In it I played the role of a human ball that is hung from the ceiling and Hijikata dances around me, at times swinging me and at times avoiding me. (Laughs) I went with Hijikata as his assistant when they filmed his solo dance scene on location on the Noto Peninsula. The first thing I did every morning after waking was to make well sweetened coffee for Hijikata, then he would put on his costume, which was a woman’s wedding kimono, and go out into the water on the seashore to perform his dance. When the kimono got wet it was my job to do my best to dry it out. It was the time I have very strong memories of, but in fact my time with Hijikata was short, just a little more than a year.

- Hijikata presented what would become one of his most famous works, Shiki no tame no Nijushichiban (Twenty-seven Nights for the Four Season), in 1972. That was the year that you joined with Akaji Maro to form the butoh company Dairakudakan. Looking back, the founding members of Dairakudakan were certainly an impressive group, including Ushio Amagatsu , Bishop Yamada and Isamu Ohsuga, who led the Byakkosha company which now suspended activities. How did you decide to join in the founding of Dairakudakan?

- I had returned to Waseda University and was working on my graduation thesis, researching the “mountain priests” ( yamabushi : *3 ). I went to the three holy Dewa mountains [of Japan’s Yamagata prefecture] to see the mummified priests ( sokushinbutsu ) and such things, but at the same time I was earning money dancing in the gilded body shows in the cabarets. Just around that time I heard that Maro-san had left the Jokyo Gekijo theater company and was going to start something new, so I decided to go see what he was going to do. Eventually I quit my graduation thesis and withdrew from Waseda University.

- I’d like to talk a bit more about the subject of the mountain priests ( yamabushi ). When I look at your dance today I feel something closer to the mountain priests than to American pop culture for example, wouldn’t you say? The mountain priests are an extension of the worship of holy mountains, which is a kind of nature worship in which devotees walk around the mountains with one pair of straw sandals and a few rice balls. There seems to be something in that which is close to your activities today, but although some anthropologists sometimes get involved with research of the subject, I’m surprised you were doing that at such a young age. I imagine it is quite rare for students to be doing that. What got you involved in it?

-

It was the subject of death and regeneration. It was the “mountain” as a form of initiation, or you might say animism. I was interested in getting a more tangible physical experience, and I was also interested in the disreputability of the mountain priest because they walked a path somewhere between the holy and the worldly and the way they pursued a “wandering life” without any religious or group affiliation. I think the ambiguity and the equivocal nature of the “trickster” can be restated in terms of dubiousness, disreputability or being variant in nature, while on the other hand I believe it also connects to a light and easy mobility or fluidity. There is also a part of me that finds it difficult to stay in one place too long. There is a kind of life that refuses to affiliate itself with any given authority, like the

matatabi

(wanderer) or

yakuza

gangster, or the

sutasutabo

(sutasuta Bozu:

*4

) like the Buddhist priest Ippen Jonin (Yugyo Jonin, Sutehijiri:

*5

) who spent his life traveling, unattached to any single temple, and then there is also the cabaret performer. When I was a child I often got separated from my parents and became lost. Despite the uncertainty and fear of being lost, there was also a feeling that being lost was the true state. That is why I am still a wandering

sutasutabo

unable to stay in one place even at this age. (Laughs)

- In 1974 the women’s butoh group Ariadone no Kai was formed. Both Maro-san and yourself choreographed for them. Then in 1976 you started the first all-male butoh company Sebi. Did the fact that you based your company deep in the mountains of Fukui Prefecture have anything to do with your mountain priest studies?

- I was first involved in Ariadone no Kai as a producer. The company’s early trilogy Mesukazan was directed by Akaji Maro. At the time, I was also involved in creating Dairakudakan productions and publishing the newsletter Hageshii Kisetsu in my activities under Maro-san’s philosophy of Tempu-Tenshiki (A term created by Maro, meaning, “Being born in the world is a great talent itself.” *6 ) and Ichinin-Ippa (One dancer, one school), meaning that every butoh artist must be independent and have a style of their own (be a school unto themselves). That is the philosophy that led to the birth of [Dairakudakan outshoots] Hoppo Butoh-ha and Sankai Juku. And I started my own Sebi company. As to why I chose a base in the mountains of Fukui, of course it wasn’t to doing farming up there. I needed a place that wasn’t a place, someplace very sparsely populated, a place “outside” the society. If my travels with the cabaret felt like lateral crossings of Japan as we toured, when I opened my un-studio-like studio in the mountains I gave it the name Hokuryukyo to suggest my intention of nurturing a contrasting vertical feeling of that boundary space. I wanted to share with the audience my own personal questioning of what it meant to practice dance and what it meant to hold performances. When I presented Komuso (mendicant monk) as the maiden show of my new company in 1976, I was the only member of my company Sebi and the work was performed by the members of the Dairakudakan group and Maro-san served as director. That was the first time that I danced as a mummy and it became quite an event that brought an audience of more than a thousand people from far and wide to my remote mountain studio. Hijikata-san came with some of his students and involved the local people to make it an exciting event. In an edition of Asahi Graph magazine at the time it was praised as quite an interesting event.

- In 1978, you and your Sebi company held joint performances in Paris with Ariadone no Kai. They were truly epoch-making performances that introduced the world to the butoh dance form. How did that overseas production come about?

- The original invitation was for Hijikata-san, but he didn’t go. He didn’t like flying. Dairakudakan was also invited and Maro-san said he wanted to take a big production with about 40 people. But that turned out to be difficult to manage. I was in charge of production, so I went to Paris in 1977 in the name of a preparatory survey. Since I was going there anyway, I made a request that I be allowed to dance at a cabaret there in Paris, and it turned out that a newly opened cabaret named Jardin was open to the possibility, so I contacted Carlotta Ikeda and Mizelle Hanaoka and asked them to join me. It turned out, however, that the cabaret’s mannequins refused to dance with Japanese underground performers, to the contract never materialized. So I turned to the task of finding a place to have our companies’ full-scale performances in Paris. I found the experimental theater space Nouveau Carre – Silvia Monfort which was just right. That is where we performed the work Dernier Eden – Porte de L’au-dela consisting of Bokukazan and my mummy dance. There were big reviews of our production in the newspapers Libération and Le Monde and despite being late-night performances in mid-winter February, the audiences kept growing.

- That is amazing.

- The Libération devoted a full page to the review, with an impressive display of photographs. Back in Japan, Yukou Deguchi wrote about it as the Paris Debut of Ankoku Butoh in the Nihon Dokusho Shimbun paper. From that time onward, the Ankoku butoh meaning Danse de tenebre and the dance we were doing came to be commonly known as Butoh.

-

Devoting a whole page of a nationwide newspaper to underground arts like butoh was at the time is unthinkable here in Japan. It was a case where being recognized that way overseas first spread awareness of butoh among the public in Japan, in a process that you could call reverse import, wasn’t it? It was the same of [film director] Yasujiro Ozu who wasn’t really noticed in Japan, perhaps because his films were so Japanese, until the fact that he became recognized in Europe led the Japanese to rediscover him. Those performances in 1978 laid the foundation for your many years of performance in Europe since, didn’t it?

After that you performed primarily overseas. There you presented your first fully choreographed works like Zarathustra in the first half of the 1980s. - The title of that work is taken from Nietzsche and I premiered it at the Sogetsu Hall in Tokyo’s Aoyama district before touring with it in the cities of Europe.

- Where were you in 1986, the year that Hijikata died?

- I was living in Paris, but I happened to be back in Japan for performances at the time. So I was just able to make it to the funeral. He died in January and I was thinking about canceling my performances of Hyohaku suru Nikutai (The Wandering Body) scheduled for March. In the end, I decided to add a memorial passage at the last moment and go ahead with the performances. I also made the production I had been working on in Paris as part of the UNESCO 40th anniversary celebrations a Hijikata memorial production. That was a production in which I invited 50 dancers from Europe to perform a work titled PANTHA RHEI in the butoh style with their bodies whitewashed. All the men and women dancers performed in the whitewashed body (no costume) style on a stage constructed in the form of a large staircase that they snaked up like a human chain crawling toward the ceiling. It had the appearance of a cycle of rebirth, like a William Blake painting. (Laughs)

- In the latter half of the 1990s you presented the work Edge . The word edge itself carries a wide range of images, I believe. From the standpoint of the viewer, the word edge seems to imply what might be thought of as a dangerous “edge” where you have always placed your body as a dancer. It seems to imply like a precarious edge where you deliberately position your body.

- My “Edge” may be the dangerousness of boundaries. In short, the more you internalize your body, the more you are likely to come in contact with the external. I wrote an essay titled “Hinagata” (form of eternal darkness), and in it the word edge is used with regard to what I think of as the “edge of the body” or things that can be found in deep corners [of the body]. This is a concept that I have always been concerned with, ever since I danced the mummified body for the first time.

- You have conducted many workshops overseas, at venues such as the Vienna’s ImPuls Tanz festival and the Centre National de Danse Contemporaine in Angers, France. By nature, your dance works appear to be ones that could only be performed by your own body, so it interests me what you would teach in your workshops.

- It is all about breathing and the “axis” of the body, and where these two intersect or interlock. In short, it is a question of the state where balance equals imbalance, and what that means is the balance of “edge.” In order to have full awareness of the state of the body getting out of balance, you have to begin by learning to recognize when you are [the body is] in a state of balance. But the state of balance is something that is impossible to maintain. You can think of the state where you are one with the body’s axis as a state of death, in other words a dead body. Of course it is not actually a dead body, so you can never be completely aligned with the axis, but there are instances when it happens in the body and those moments can be thought of as simulated death, as moments when time is captured, or reflected. It is a delicate balance and the state of being off balance can be thought of as “life” (the state of being alive). In other words, life is a repetition of going off balance, deviating from the body’s axis. The feeling of being alive and breathing is a constant state of motion off-center from the body’s axis, and folded into the cracks of that process are moments of death. Breathing is a process of constant recurrence and circulation, but there are moments of death folded into the process, which is very paradoxical and simultaneous in nature. Time that can be counted out (1, 2 …) and time that can’t be counted exist simultaneously, in parallel, and both of these forms of time are alive in the body.

- That is a difficult concept to grasp, isn’t it? Hearing you describe this concept of countable time and uncountable time alive simultaneously and that the dancer’s body is created in the process of going back and forth between the two, it would seem to me that perhaps many conventional dancers will not grasp that concept. Because, generally, dance is most often movement performed in rhythm with countable beats.

- This is why, conversely, you can call butoh a form of dance defined by flow and by the “dangerous fragility” and “intrepidness” of life [the life force within living things].

-

Isn’t this aspect perhaps one of the reasons why the butoh form created by Hijikata continues to live on today?

Changing the subject, may I say that your uniquely arched back with its exceptional development of broadest muscles of your back seems to be even more prominent and stronger now than it was 20 years ago. I can’t imagine that you go to the gym and work out with barbells to develop those muscles. How do you keep them so developed? -

Well. I am not consistent, but rather haphazard by nature. I don’t do my training every morning before I go out to meet people. (Laughs) Speaking of the unique traits or peculiarities of the body, in fact every body is unique, with its own peculiarities. So I don’t think in terms of trying to correct a rounded back or slumped shoulders. I say, go with your rounded back. There is a nobility to wild animals, there is an elegance in wild grasses and weeds, and I have a strong interest in, or even an obsession with animal qualities. There are certain speeds and strengths [of motion] that are instinctual. Human beings are animals, but we are also plants, and minerals. We are not just bipedal walkers, we also can hop on one leg or do a four-legged walk, or walk blind, we can be composites of different natures, like cat and dog, or flower and stone. It is rather this kind of unhinging, these moments of what Hijikata called this “

Yaban de sensai

” (Savage subtlety/sensitivity) that fascinate and obsess me.

I spoke earlier about breathing, and I would say that there are transitional moments when it is dangerous to simply breathe normally. There are times when chills run through us and moments when we swallow our breath, and there are times when our breathing stops unconsciously while we talk in our sleep. When you actually try walking like a four-legged animal, you can move toward a different “outer time,” time that is outside the normal counted time you are used to when standing up and counting so you can move in rhythm with a beat. Whether it is a metamorphosis of life or a revival of life, to make that feeling one of your physical assets, I wouldn’t say that you have to train yourself to do that, but I do believe that you have to do it repeatedly. - In Hijikata’s terms it is a process of collecting the parts that have fallen away [from the body/motion in common use], isn’t it? In his later years, Hijikata talked about suijakutai no saishu (collecting/harvesting the weakened body) and that may be one of the most essential definitions of what makes butoh unique. In other words, I think the musculature of the [dancer’s] body that has been created only through rhythms that are counted out and the musculature of the body created by actively seeking and picking up the parts of the body/movement that have fallen away from that kind of [dancer’s] body will, of necessity, be different, and the movement that comes from those two types of bodies will be different too.

- Yes. The pinnacle of Hijikata’s art may indeed be the “weakened body” concept. It was probably his stance not being bound to the rule that dance is done on two feet but, rather, that it is something to be built up from what you might call “incapability.” Hijikata-san spoke of removing the normal pause/interval ( ma ) or timing, and left the term magusare (deterioration of interval) and it is based in the concept of a body that has fallen out of some type of productive role, and it is disfunctionality or incapacity, or you could call it impotence, I think. The reason he was so obsessed with the idea of impotence, I believe, it was probably a residual effect of the War (World War II). He was thinking about a communal body that could connect to what you could call a type of incapability or malformation. I spoke about High Red Center earlier, and in their inclination toward things criminal or delinquent there is an element of the excessive or drop-out behavior we see in the people that will always resist and head in a different direction when the society calls for everyone to come together and work in the one productive direction. Amanojaku (contrary person) is an example of one who always looks in the opposite way when everyone is looking in the same direction. So, who is this amanojaku that is always looks the opposite way? You will always find this kind of element in society, and I think that is the reason in itself. It is not simply a political question.

-

But, in a broader sense that is also a political question. In society it is never the case that a hundred people will all be heading in the same direction. There will always be many bodies among them that can’t do that and not all people have positive productive potential. There are bodies that will go against that and bodies that may want to but are incapable of it. I believe that [Hijikata’s]

suijakutai

(weakened body) is how you pick up and make use of those discarded parts as the basis for artistic expression.

With your works and your workshops you have made a great contribution toward making butoh an international art form. Looking toward the future is there anything that you feel you have still left undone? - It is returning to my original inspiration. Butoh is not something to be danced for the gods or for the Japanese. It began from things that didn’t belong to any of the traditional forms of artistic beauty and things that could never become part of those forms. In a way, I began dance because I couldn’t dance and I didn’t want to dance. Something that I wrote long ago was that “I began dance in order to die.” I didn’t just say that simply as a metaphor, I believe. I want to go back to my original inspiration and find why I began with dancing as a mummified body. The bodied of the drowned that I saw on the beach as a child may be my original point of departure. The physical movement of dance is not simply a matter of moving around. There is also physicality folded into a state of immobile stillness, and I believe that getting to the source of that involves a process of constant and ongoing experimentation. And that is not simply a matter of continuing to dance. I believe it may also be done by going on to the next world without ever dancing. As for whether I have left things undone or not, it may be leaving things undone endlessly. In other words, dance has no beginning and it has no end.

Ko Murobushi

The body at its physical edge A solitary presence among Butoh artists, Ko Murobushi

Ko Murobushi

Choreographer, butoh artist. Apprenticed under Tatsumi Hijikata in 1969. In 1971 he conducted research on the yamabushi (mountain worshipers) of the Three Holy Mountains of Dewa. In 1972 he joined in the founding of the butoh company Dairakudakan and participated in numerous productions while also serving as a producer for the all-women’s butoh company Ariadone no Kai. In 1976 he started his own butoh school Sebi and opened a studio called Hokuryukyo in the mountains of Gotaishi-cho, Fukui Prefecture, where he performed Komuso (mendicant monk) as his company’s maiden show. In 1978 he participated in the production we performed the work Dernier Eden – Porte de L’au-dela, which enjoyed a well-received month-long run that spread the name “BUTOH” on the world scene for the first time. Since then he has been invited to many festivals with highly improvisational solo performances. From 2000 Murobushi began full-fledged performance activities in Japan beginning the work Edge performed at Kagurazaka die pratze. In 2003 he started the unit Ko & Edge Co. with a group of young performers and presented the work Handsome Blue Sky ( Bibo no Aozora ). In 2005 he was presented the Award of the Performing Arts Critics Association. In 2006 he presented the work quick silver at the Venice Biennale. Murobushi has also taught at the Centre National de Danse Contemporaine in Angers.

Interviewer: Tatsuro Ishii [dance clitic]

*1 High Red Center:

An avant-garde artist group formed by Jiro Takamatsu, Gempei Akasegawa and Natsuyuki Nakanishi in the first half of the 1960s. The group name derived from the first characters of the family names of the members: taka (high), aka (red) and naka (center). The group became known for happenings such as the “Yamanote Line Incident” in which they licked objet creations on the platforms and in the cars of the Yamanote train line, and the “Metropolitan Area Cleaning Promotion Movement” in which they appeared on streets of the Ginza district of Tokyo in white smocks and surgical masks and began cleaning the sidewalks. Akasegawa’s work “Thousand Yen Bill Incident” in which he printed fake 1000-yen bills brought him under criminal investigation for counterfeiting.

*2 Zenkyoto:

Abbreviation of the Zengaku Kyoto Kaigi (The All-Campus Joint Struggle). The representative association of the radical student movements that started at the campuses of Tokyo Univ., Nihon Univ. and others in 1968 and 1969 and spread throughout the country.

*3 Yamabushi (mountain worshipers/priests):

Yamabushi are ascetics who retreat in the mountains and undergo strict training including ten disciplines of fasting water abstinence and others in pursuit of rebirth.

*4 Sutasutabo (Sutasuta Bozu):

Mendicant priests of the Edo period who wore rope headbands and ropes around their waist and often carried a priest’s ringed staff and begged for alms by dancing.

*5 Sutehijiri:

A priest of the Kamakura period also known as Yugyo Shonin. Throughout his mature life he traveled throughout the country without affiliating himself with any specific temple and taught the common people Buddhist worship through dance and prayer recitation.

*6 Tempu-Tenshiki :

A term created by Akaji Maro expressing the belief, “Being born in the world is a great talent itself.” It is the basis for Maro’s philosophy of and Ichinin-Ippa , meaning that every butoh artist must be an independent “school unto themselves.”

Photo: Rodorigo Yamamoto

Photo: Kimiko Watanabe

Related Tags